Anniversary of a Myth: The Knickerbockers’ Most Famous Game

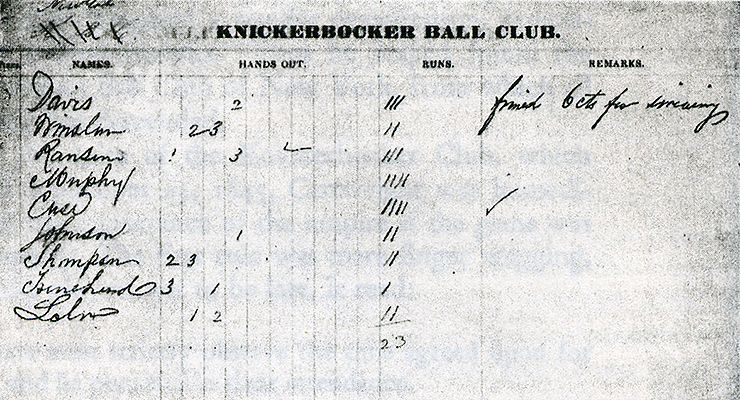

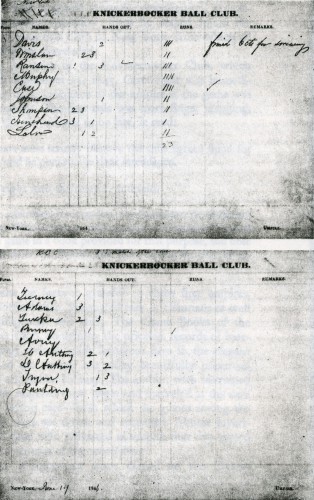

This is one of the first versions of a box score. (via New York Public Library)

One hundred sixty-nine years ago today, the New York Knickerbockers played one of the most famous baseball games of all time. The team often credited with writing down the first formal set of baseball rules took on a club called the New York Nine at a pleasure park called the Elysian Fields in Hoboken, N.J., and lost in a laugher, 23-1. For his role in this game and others, Knickerbockers co-founder Alexander Cartwright has a plaque at the Hall of Fame in Cooperstown which names him “Father of Modern Base Ball.” For decades, historians believed that the June 19 match was the first organized baseball game ever played.

It wasn’t. In fact, almost none of that is strictly true: Cartwright wasn’t the most important Knickerbocker, the Knickerbockers probably didn’t write the first baseball rulebook, their victorious opponents were never called the New York Nine, the game itself may have been more intramural than a true match game, and in any event the Knicks played their first games in the fall of 1845 (and their first match games were probably in the 1850s).

The enduring fame of this particular game and of its players is the product of circumstance and self-aware myth-making. As the official historian of Major League Baseball, John Thorn, has written: “The history of baseball is a lie from beginning to end, from its creation myth to its rosy models of commerce, community, and fair play.” The myths I recounted in the first paragraph endure on Cartwright’s Hall of Fame plaque, in a 1960 tome called Baseball: The Early Years, which its author calls “the first scholarly history of baseball’s early years by a professional historian,” and even on the official website of the State of New Jersey.

But there was a game played on June 19, 1846, it was in the Elysian Fields, and the team that beat the Knickerbockers 23-1 was named New York. If the game that is remembered best is not precisely the first game that they or any other team ever played, it is still perhaps the truest baseball myth of its era. The Knickerbockers did not invent modern baseball, but they did more than perhaps anyone else to midwife it.

A chief contribution that the Knickerbocker Club made, says historian John Husman, was to make what had been a children’s game more palatable to adults. “The club was a social club, and they had a ball team,” he says. The group who founded the club in 1842 were leisure-seekers, not athletes: in his book, Thorn describes the founder’s generation to a man as being “composed of flaccid professional men.” According to Husman, just as important as the game itself was how they celebrated afterwards: “eating and drinking and smoking cigars.”

Remarkably, thanks to the early Knickerbockers’ fortunate obsession with documentation, we have primary sources for their games, particularly thanks to a member named James Whyte Davis. Their game books, displaying lineups, outs made, and runs scored by player are on microfilm in the New York Public Library. Here is the one for the June 19 game, which Thorn displays on his own blog (click the picture for a larger version):

There are nine men to a side, but Thorn notes that the position of shortstop had not yet been invented, so there were three infielders and four outfielders. Cartwright also wasn’t in the lineup; as Thorn writes, he umpired the game “and enforced a six-cent fine, payable on the spot, for swearing.” The game lasted only four innings, because the Knickerbockers’ original rules provided that the game would stop at the end of the inning after one team had scored 21 runs — the nine-inning rule came much later. But in other respects it was similar to the game we still play. “You would recognize the game,” says Thorn. “You have three outs to the inning, three strikes to the at-bat.” Perhaps most incredibly, he notes that the rules specified that “if the catcher fails to hold onto the third strike, the batter must run.”

Their name, of course, lives on in immortality, and there is a connection there. Before they began playing in New Jersey, the Knickerbockers originally played in a garden on Madison Hill in Manhattan, which inspired the name of a venue for a team with the same name that plays a different sport. (Madison Square Garden has long since left Madison Square. But the Knicks are still called the Knicks.)

The Knicks were not the first club in New York, however. In fact, the New York club that they faced on June 19 predated them. A close examination of the two lineups indicates that the two clubs shared a number of players, and indeed many of the Knickerbockers were former members of the New York Baseball Club, which was also variously known as the New Yorks, the Gotham Club, or the Washington Club. As Thorn notes, William Rufus Wheaton, a former New York, claimed that the 1845 Knickerbocker rules which he helped to write were largely based on a set of rules the Gothams adopted in 1837. The 1837 rules are lost to history, but Thorn considers Wheaton’s testimony “entirely credible.”

Moreover, New York was not the only part of the country where baseball was played. There were a number of regional variants, many of which had far more adherents in the 1840s than did the “New York game” of which the Knickerbockers became the most famous exponent. In Connecticut, they played a cricket variant called wicket; in Philadelphia, they played a game called “town ball.” In Massachusetts, for example, there was no concept of foul ground, which may have made the game more fun to play, but as David Block points out, this also may have made it more difficult to develop as a spectator sport.

Other rules differed, as well. In the Massachusetts Game, runners were thrown out by being “soaked” — i.e., pegged with the ball. (As in modern kickball, for example.) In addition to requiring the ball to be thrown to a fielder rather than at the runner, a major innovation that the Knickerbockers pressed for was to require that balls be caught on the fly; previously, a ball that was caught on a single bounce was considered an out. And in the New York game, pitchers “pitched” the ball rather than “throwing” it — they tossed it underhand, keeping a stiff elbow. It was very much a hitter’s game, as evidenced by the 21-run rule.

New York’s variant triumphed in part because New York triumphed. “We play the New York Game today rather than the Massachusetts Game,” Thorn wrote to me, “because the Knicks were superior public-relations managers.” While cricket likely dwarfed baseball in popularity across America before the Civil War, after the war the New York game quickly became the national game. The Knickerbockers, who had kept the faith for 20 years before Appomattox, played a major role in keeping the game active. Baseball also represented what historian Peter Morris calls “a compromise with the Puritan ethic”: it may not have been quite as wholesome as church, but it was certainly a better leisure activity than spending time at racing tracks, billiard halls, or brothels. Social reformers who might have denounced these other activities could accept and promote baseball.

It is hard to pinpoint the game’s precise age. Humans have been playing bat-and-ball games for millennia, and children don’t typically leave documentary evidence of the games they play. But recent research, much of it by David Block, has demonstrated that a game called “baseball” or “base ball” had been played in England more than a century before the Knickerbockers got together. Block found a German book from 1796 that listed the rules of various games, including “das englische Base-ball,” 50 years before the Knickerbockers wrote down theirs. A half-century before that, in 1744, English writer John Newbery wrote a brief poem in one of his books for children:

Base-Ball.

The Ball once struck off,

Away flies the Boy

To the next destin’d Post,

And then Home with Joy.

(The Newbery Medal in children’s literature is named after this same John Newbery. You’ve probably read some of its honorees, like A Wrinkle in Time, Maniac Magee, and The Giver.)

Baseball’s most baseless myth is the story that it was invented by Abner Doubleday, a Civil War general who was posthumously put forward during a power struggle over baseball’s official past. The Hall of Fame is in Doubleday’s hometown of Cooperstown despite the fact that there are no records that he ever even played baseball. In his book Baseball in the Garden of Eden, Thorn amasses a good deal of evidence that Doubleday’s name was put forward by Al Spalding, the Hall of Fame pitcher and sporting-goods titan, for two reasons.

First, Spalding patriotically wished to establish forever that baseball’s origins were purely American, not English. But the second reason was weirder. In his later life, Doubleday had become the president of the Theosophical Society, an esoteric Mason-like movement based on the writings of an itinerant charlatan named Madame Helena Blavatsky, and like Doubleday, Spalding and his wife were devoted Theosophists. Spalding, therefore, may have believed that Doubleday was spiritually the right fit.

Incensed by this, members of Alexander Cartwright’s family fought back and put forward their own progenitor as the “true” father of baseball, earning Cartwright a plaque in the Hall of Fame in Doubleday’s hometown. (Update: “Hometown” is inaccurate; rather, he had family there. See the comment below.)

Despite all of that, nearly a century ago — and despite Cartwright’s somewhat-less-inaccurate Hall of Fame plaque to the contrary — as recently as 2011, Commissioner Bud Selig professed to believe that Doubleday had invented baseball. Spalding succeeded in obscuring baseball’s English roots, even if in doing so he partly muddied its true American history.

But he couldn’t hide the evidence of the game on June 19, a four-inning slugfest that took place without crowds of fans, without media, before anyone had any idea that the game would be more popular than Massachusetts baseball or town ball or wicket or cricket. Even if the game is remembered for the wrong reasons, it is remarkable that it is remembered at all.

References and Resources:

- Inventing Baseball: The 100 Greatest Games of the Nineteenth Century — edited by Bill Felber, Society for American Baseball Research (2013)

- Baseball in the Garden of Eden — by John Thorn (2011)

- But Didn’t We Have Fun?: An Informal History of Baseball’s Pioneer Era, 1843-1870 — by Peter Morris (2008)

- Baseball: The Early Years — by Harold Seymour (1960)

- The book of American pastimes: containing a history of the principal base-ball, cricket, rowing, and yachting clubs of the United States — by Charles Peverelly (1866) (as noted in this blog post by John Thorn)

- Spiele zur Übung und Erholung des Körpers und Geistes — by Johann Christoph Friedrich GutsMuths (1796) (as noted in Baseball Before We Knew It by David Block)

- Phone conversations with John Thorn, Peter Morris, John Husman, David Block, and Tom Shieber

Nice article. I always appreciate those that try to correct lies and myths like this.

Here’s another piece of evidence that baseball isn’t strictly American. It’s a painting from the 14th Century from Belgium and it looks like baseball to me.

http://art.thewalters.org/detail/21564/the-ghistelles-calendar/

That is an awesome picture, and from 700 years ago, too!

Has John Thorn said anything about this painting?

David Block, one of the people I quoted in the piece, offers a small correction: “Cooperstown was not Doubleday’s home town. He had family there, but was born in Ballston Spa and grew up in Auburn. Oddly, there is no hard evidence that he ever set foot in Cooperstown.”

Great article. Very entertaining