Ending the LaRussa Orthodoxy: Part 2

Tony LaRussa’s bullpen strategy actually leans toward removing starters too early rather than too late. (via Dirk Hansen)

In Part 1 of this series, we looked at the evolution of relief pitching strategy and found four different phases, with what I called the LaRussa Orthodoxy–multiple relievers, matchup focused, closer-driven– the latest iteration. We asked whether bullpen performance really justifies reliance on this strategy and whether it too, like other previous relief strategies, is ready to be superseded. In Part 2, we will try to answer these questions.

As I delved into this investigation, I was heartened that Bill James had posed a similar set of questions in his essay on the modern bullpen:

Now, it is very much an open question whether this is an optimal strategy. Does an effective relief ace have the greatest impact on the won-lost record of his team when he is used only to close out narrow victories, or might he not have equal impact, or even greater impact, if he was used as Elroy Face was used? I don’t know the answer to this question; I don’t think anybody else knows either.”

Bullpen Performance Under the LaRussa Orthodoxy

Rather than being constrained by evaluating the performance of relief pitchers in the roles prescribed by the LaRussa Orthodoxy, I decided to look at bullpen performance as a whole both prior to the adoption of the Orthodoxy and after. Going back to first principles helps: What do we want a bullpen to do? First and foremost, we want it to take the team to a victory. That means holding a lead when the starter departs. It also means not being responsible for a loss. And since we are evaluating a system with the closer as its centerpiece, asking how well the closer does his job is important.

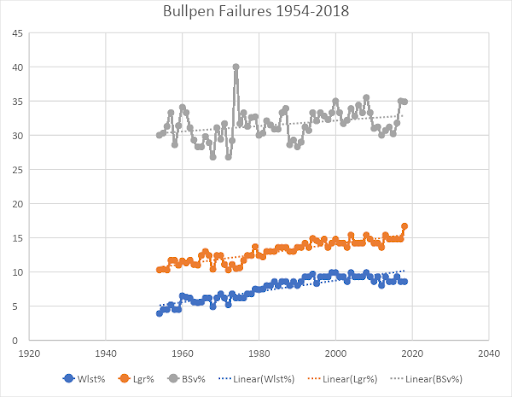

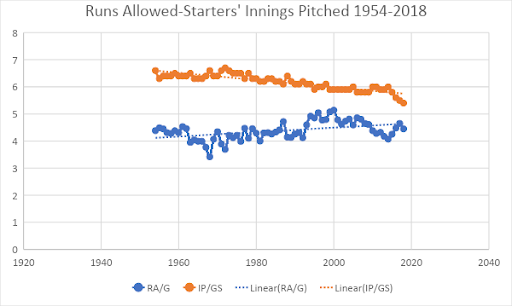

Accordingly, I examined data from 1954 through 2018 in Baseball-Reference.com on games lost when the starter departed with a lead (Wlst), games where the bullpen took the loss (Lgr), and blown saves (BSv). I stopped at 1954 because Baseball-reference.com says that statistics for pre-1954 seasons at the level I was seeking should be viewed as incomplete. Raw numbers needed to be adjusted since the number of games played changed from 154 to 162 per season, and in any given season the totals could vary a bit. In addition, there were strike-shortened seasons to deal with. Thus, on a season-by-season basis, I calculated Wlst and Lgr as percentages of games played as well as the BSv percentage of save opportunities for the major leagues as a whole. It also seemed pertinent to consider runs allowed per game (RA/G) and innings pitched per game (IP/G).

Here is what I found, presented graphically:

Some observations:

- If the relief strategy driven by the LaRussa Orthodoxy was supposed to lead to better bullpen performance, it, in fact, did not achieve its goal. Dating the advent of the Orthodoxy from its inception in 1989–or, more accurately, somewhere in the 1990s–we can see that it did not result in more wins preserved after the starter departed with a lead, nor in fewer losses incurred by the bullpen. Rather, there have been more bullpen failures during the Orthodoxy’s primacy.

- The paragon of the Orthodoxy–The Closer–hasn’t made much difference. Blown saves show some volatility, but they have hovered around 30 percent of save opportunities throughout the period of 1954-2018. Interestingly, the lower percentages are before LaRussa introduced the approach, and except for one year (1974), the highest percentages have been after, with an uptick in the last couple of years.

- Runs allowed per game have hovered around 4.5. Generally, they have gently climbed over the period–not declined as one might have expected if bullpens were effectively locking down games.

- Innings pitched have declined, consistent with the widely understood phenomenon of disappearing complete games and the growing practice of limiting starters’ times through the batting order. This may have contributed to the increases in Wlst and Lgr percentages since fewer complete games would mean more opportunities for bullpens to lose leads and games. Nonetheless, the strategies for starting and relief pitching do not exist in isolation from each other. I would argue that belief in the LaRussa Orthodoxy at least contributes to a willingness to lift starters earlier, reinforced by concerns about starters’ growing ineffectiveness as they go more times through the batting order.

Thus, stepping back to examine whether bullpens are doing what we want them to do, we can see that there is no reason to consider that the LaRussa Orthodoxy has had a positive impact or represents a more effective relief strategy. The 1989 Athletics’ bullpen was undoubtedly great–8.0 Wlst%, 10.5 Lgr%, 24 BSv%, 3.56 RA/G–but rather than demonstrating the advent of a better strategy, they were just very-good-to-great individual pitchers. Not every team can have Dennis Eckersley.

Indeed, the upward climb of bullpen failures suggests that a time is coming when the LaRussa Orthodoxy will begin to crack. The 2019 season indicates that this time has arrived. A few illustrative headlines show the widespread dissatisfaction with bullpens’ performance:

“The bullpen was a disaster again, and the Red Sox were swept by the Yankees”

“Bullpen issues overshadow Yelich’s 32nd homer”

“Jerry Seinfeld might be ready to help Mets bullpen after perfect first pitch”

“Cubs at a loss after pen squanders leads again”

“Disappearing triples! Imploding bullpens! How baseball is different in 2019”

Clearly, something has gone wrong within the prevailing Orthodoxy.

In the search for answers, one prevailing issue is that of bullpen workloads. As the number of complete games approaches the vanishing point, and with the Times Through the Order Penalty a widely accepted reality, it necessarily means that more will be asked of bullpens. Relievers have been setting volume records for share of pitches thrown and innings pitched. Games in which managers used at least five relievers have spiked. As Andrew Friedman of the Dodgers points out, “We as an industry have learned a lot about managing starters’ workloads and appreciating various increases and what that means, and we have no idea on relievers.” The Cubs’ Theo Epstein adds that “more is being asked of bullpens. You start accumulating seasons of the starter getting pulled the second time through and more burden placed on the pen, it’s going to take a toll.”

The toll is being paid. For half a century, relief pitchers have had a lower ERA than starters. This year, relievers’ ERA is the same as starters‘; just three years ago, relievers’ ERA was almost half a run lower. Bullpen ERA is the second-worst in the past 69 years; only 2000, in the steroid period, was worse. ERA in innings seven through nine has jumped. Relievers’ strikeout rate advantage compared to starters has dropped as well.

Another line of thought is that bullpens and relief pitchers are inherently volatile and unpredictable. Dodgers manager Dave Roberts notes the scarcity of relievers who are consistently effective over even three or four years in a row. Friedman sums up by saying, “Every year … the bullpen performance is what keeps me up at night. And it’s funny because the years that I’ve had the most confidence is probably the years where we’ve struggled the most, and the years where I’ve been the most afraid are the years where we’ve been the best.”

The data bears out what they say. In his article “So You Want to Have a Good Bullpen,” Jeff Sullivan looked at bullpen projections, and concluded that “bullpens can be the hardest to see coming,” “there’s very little performance carryover” from one year to the next, “the difference between good and bad in the bullpen is slim,” and “there’s just this strong whiff of unpredictability.”

Perhaps the problem with prevailing bullpen usage can be put more simply and directly. Consider what Freddie Freeman, the Braves’ All-Star first baseman, has to say:

Look at it this way. If you bring four or five relievers into a game every night, what are the chances that one of them is going to have a bad night? Pretty good, right? And if you do use four or five every night, there’s going to be an attrition factor. As hitters, we’ve gone back to the idea of ‘Let’s get into their bullpen.’”

This, of course, stands the LaRussa Orthodoxy on its head. Rather than a strength, it becomes a weakness. Instead of a means confidently to lock down victories, it has a flaw that leads to poor performance and defeats.

Whatever the reasons, we have reached the point that Bill James suggested a little over 20 years ago. Increases in the number of pitchers used per game seem to be reaching their limit, the Closer model raises problematic questions, and the time is coming to search for a new equilibrium in relief strategy. It probably took longer than James anticipated, but as Tom Verducci puts it: “[T]his … is the Year of Bad Bullpens. The pitching model is broken. Will the game begin to adjust?”

Toward a New Theory of Relief Strategy

Some teams and commentators have already begun to search for a new approach. Brian Kenny argued for “bullpenning”–ending the starter/reliever distinction and the use of the closer only in the ninth inning, and utilizing a team’s pitchers where their strengths would be most effectively deployed as needed during any given game. Jack Moore suggested that a multi-inning fireman-closer hybrid could be effective in “Where’s the Next Willie Hernandez?” and “The Rise of the New Fireman, Josh Hader.” This May, Ben Clemens wrote “Let’s Find a Multi-Inning Reliever.” And in 2013, Bryan Grosnick proposed using “openers”–a reliever currently used in a setup role to begin the game and then give way after an inning or two to the starter. The starter would thus first face batters lower in the order and mitigate his Times Through the Order Penalty (or “TTOP”), a phenomenon discussed by Mitchel Lichtman.

Without in any way wanting to detract from efforts to find a new way forward, I can see some reservations about the various ideas they suggest. Full Bullpen Attack sounds like it could become the LaRussa model on speed. Rather than confined to the late innings, now it would be applied to all innings and thus carried out by even more pitchers. Freddie Freeman’s observation that at least one of them would likely fail and sink his team’s chances would gain more force. It may also not be as novel as it sounds. Recall that the pre-World War II approach to relief pitching was that there really were no distinct starters and relievers; good pitchers filled both roles. That approach was superseded because of the advantages of specialization.

Similarly, the Next Willie Hernandez/Josh Hader model appears to be a call for a revival of the relief ace approach that developed in the 1950s and 1960s. That model reached its limits because of the workloads it imposed and fatigue it created. For it to work, teams would need not only the ace himself, but also other top-level relievers to share the workload, Jack Moore acknowledged. Even then, fatigue could pose a problem.

The Opener proposal is intriguing, but I believe that there is another approach, in line with some of its insights, that would more systematically exploit the inefficiencies in the LaRussa Orthodoxy. Recurring to first principles, the team needs to get 27 outs. To get them more effectively than the Orthodoxy allows, my hypothesis would rest on the following propositions:

- There is a well-established TTOP, and importantly, the starting pitcher has the advantage the first time through the order.

- Most relievers are former starting pitchers.

- Many of these pitchers failed as starters because they could not go more than once through the order; their TTOP was significant and showed up by the second time through the order.

- However, they did have success the first time through the order consistent with the first proposition and thus have shown the ability to get nine outs effectively – about three innings.

These types of failed starters are relatively plentiful and inexpensive to retain and acquire.

Accordingly, a successful relief strategy could be built upon harnessing these pitchers’ talents. The strategy would consist of: (1) assembling a corps of such starters; (2) assigning them the responsibility to take over after the starts expected from the regular starting rotation, about six innings, and; (3) having them finish the game, pitching three innings or less. The pitcher heretofore designated as the closer, probably the team’s best short reliever, would be kept in reserve in case they falter. (Of course, if the team has Mariano Rivera, use him liberally. But most teams don’t have Mariano Rivera or his equal). The rest of the current relief corps could be greatly reduced.

The approach I suggest would ask these former starters to do only what they have shown they can do–go once through the order and get nine outs. This is about three innings of work, essentially what is needed after a quality start. They could be put on a regular rotation for this role and prepare accordingly, knowing that when it is their turn, they will come in to pick up where the starting pitcher has left off. The regularity of their preparation and appearances would be not so different from when they were starters. It would thus smooth their transition to a relief role and be less risky than asking them to do something they haven’t done–pitch in short stints on an irregular, on-call basis.

If the regular starter fails to go six innings and has to leave sooner, the new relief strategy is still advantageous. Instead of a bucket brigade of one- and two-inning relievers to complete the game, the team would have a prepared former starter to go multiple innings. And if the regular starter went more than six innings, the job asked of the former starter in relief would be less and the likelihood of his success even greater. Ideally, a team would have a set of three or four of these pitchers in the sub-rotation for relief. But even if a team had only one or two of such pitchers, it would still be helpful since it would lessen the load on the rest of the bullpen and its potential for failure.

My proposal is built upon the successful elements of previous relief strategies we reviewed in Part 1 of this series. But it is not a simplistic call for a return to a previous era. It looks to starting pitchers as the core of the bullpen. It recognizes the advantages of specialization. It posits multiple inning appearances as the norm. It reserves the use of the fireman/closer for when there really is a fire to be put out or the game truly is on the line.

To begin to test my hypothesis, I examined the performance of major-league starting pitchers in 2018 on a times-through-the-order basis to see if there were a substantial number of pitchers who answered my description. Using the average major league slash line of batting average, on-base percentage, and slugging percentage as the standard, along with a certain amount of judgment, I was looking for pitchers generally outside the regular rotation who had better-than-average performance the first time through the order then experienced a subsequent significant deterioration. All but five teams had at least one such pitcher, and many had more than one. Clearly, more analysis should be done to find pitchers suited to such a role. Additional seasons should be considered. Still, I view this as supportive of my intuition that teams could staff a sub-rotation of relief pitchers who struggle as starters but are capable of finishing the late innings of games after the starter has put his team in a position to win.

What are the likely objections to my hypothesis? One, of course, is the typical baseball harrumph that this isn’t the way we do things. Since this has always been the response in baseball to new ideas, strategies, and tactics, it’s not a material objection. In fact, I would argue that this type of objection goes hand-in-hand with using the Orthodoxy as a managing crutch; the manager can’t be faulted since he made all the expected moves. More serious are two points: first, that the approach I have suggested is not how pitchers are taught, developed and routinely prepare, and second, that the compensation structure and market for relief pitchers would require a substantial overhaul. We can agree with both of these points, but they are not ultimately decisive.

Player development and preparation, too, have changed throughout baseball history. If there is a better way to achieve victories, then training and preparation routines should change. In fact, the relief sub-rotation imposes less of a change on starters who make the shift to a relief role. Rather than suddenly becoming an all-out single-inning reliever, or taking on a more constrained role to which they may be ill-suited and which might fail to realize their full potential, members of the relief sub-rotation would continue to condition themselves for multi-inning performances and prepare on a regular schedule.

Preserving the relief pitcher market and compensation structure means continuing to overvalue the save. Recall that the save was developed simply as a descriptive statistic, not to guide strategy. It is evident that the tail is now wagging the dog. The whole point of markets is that they are dynamic and shift in response to better products and information. If closers can’t command the premiums they previously have, then so be it.

To teams that are tanking or, more politely, rebuilding, what do you have to lose by trying a new approach? Part 1 confirmed what Bill James noted: “Relief strategy has been in constant motion for a hundred years … we are nowhere near a stopping point.” The relief sub-rotation could be the next phase, and as you win divisions, pennants, and World Series, you could be the founders of a new orthodoxy.

References and Resources

Cameron, Dave. “So What Do We Think About Bullpening Now?” FanGraphs, October 30, 2017.

Clemens, Ben. “Are Starters Improving Relative to Relievers?” FanGraphs.com, May 10, 2019.

Clemens, Ben. “Let’s Find a Multi-Inning Reliever.” FanGraphs, May 23, 2019.

Eddy, Matt. “What Most Fantasy Baseball Closers Have in Common.” Baseball America, July 2019.

Gonzalez, Alden. “Why relief pitchers have been so hard to figure out.” ESPN.com, June 17, 2019.

Grosnick, Bryan. “Replacing setup men with ‘openers.'” Beyond the Box Score, November 26, 2013.

Grosnick, Bryan. “Liner Notes: Sergio, The First Opener.” Baseball Prospectus, May 22, 2018.

Jackson, Frank. “The Incompleat Starting Pitcher.” The Hardball Times, October 17, 2017.

James, Bill. The Bill James Guide to Baseball Managers from 1870 to Today. New York: Scribner, 1997.

Kenny, Brian. Ahead of the Curve. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2016, pp. 157-176.

Lichtman, Mitchel. “Everything You Always Wanted to Know About the Times Through the Order Penalty.” Baseball Prospectus, November 5, 2013.

McCalvy, Adam. “Bullpen issues overshadow Yelich’s 32nd homer.” MLB.com, July 14, 2019.

McWilliams, Julian. “The bullpen was a disaster again, and the Red Sox were swept by the Yankees.” Boston Globe, June 30, 2019.

Miller, Sam. “Disappearing triples! Imploding bullpens! How baseball is different in 2019.” ESPN.com, April 16, 2019.

Moore, Jack. “Where’s The Next Willie Hernandez?” The Hardball Times, October 26, 2016.

Moore, Jack. “The Rise of the New Fireman, Josh Hader.” The Hardball Times, May 17, 2018.

Rogers, Jesse. “Cubs at a loss after pen squanders leads again.” ESPN.com, July 28, 2019.

Sarris, Eno. “About that Dodger Bullpen Usage.” FanGraphs, November 7, 2017.

Sheinin, Dave. “Bullpens buckling under bigger loads.” Washington Post, D5, May 19, 2019.

Sullivan, Jeff. “So You Want to have a Good Bullpen.” FanGraphs, March 5, 2018.

Townsend, Mark. “Jerry Seinfeld might be ready to help Mets bullpen after perfect first pitch.” Yahoo Sports, July 6, 2019.

Verducci, Tom. “The Year of Bad Bullpens: MLB’s Pitching Model is Broken.” SI.com, June 24, 2019.

I’m all for teams thinking about new ideas to see if there’s a better way to use relief pitchers. I think the real key is seeing if multi-inning appearances would allow the more effective relievers to pitch more innings over the course of a season.

Here’s my interpretation of the increase in reliever ERA/FIP – relative to starter ERA/FIP – in recent years. Innings pitched by relievers have increased from ~35% of innings in 2015 to ~41% of innings this year. That averages out to approximately 90 innings per team.

From 2002 to 2015, reliever innings were in a range between ~33% and ~35% of total innings pitched. (Those figures are all from a Craig Edwards Frangraphs post on 8/21/19.) The increase in reliever ERA/FIP relative to that of starters is particularly noticeable for lower leverage innings pitched by relievers.

My interpretation of that combination of facts is that what we’ve seen is that bullpen use has reached the point where the incremental relievers being used to pitch innings are of very poor quality due to dilution of talent. What more or less happens for teams is that managers max out (or close to max out) use of better quality relievers and then distribute workload down the chain, so we’ve reached the point where quality of incremental bullpen innings *really* declines as the total bullpen workload increases.

To go back to my original point, I therefore agree that it’s interesting to see if a smaller number of multi-inning appearances would allow for better relievers – at least quality set-up relievers – to pitch more innings over a season. There’s also the question of whether such a set-up leads to pitching high enough leverage innings that a team increases a measure such as total bullpen WPA.

All of that said, I have issues with a couple particular ideas presented here.

Truly limiting a pitcher to no more than one time through the order doesn’t allow him to pitch about 3 innings. It’s more like 2 innings with typical stats for PA’s per inning, especially if 9 batters is truly a hard cut-off.

Second, I don’t think that the sort of failed starters described by the author are as “relatively plentiful and inexpensive to retain and acquire” as he indicates. These logically are the sort of players who are also effective as 1-inning “LaRussa orthodoxy” relievers, and it’s been a notable trend over the past few years that quality set-up relievers are commanding bigger free agent contracts than used to be the case.

Two things

First – I’ll bet that a significant part of the increase in RP innings is low-leverage innings – and I’d also bet that those tend to be strung together in the same game. So one strategy is fill up those innings with multi-inning appearances by the relievers at the lower end of the bullpen. Every one of those appearances will essentially provide both a day off for the higher end of the bullpen in a game where using them would be a waste and eat up a lot of those estimated innings/yr that are needed. A reliever who can appear 40-50 times/year and eat up 100+ innings seems to me to be a very use of a roster slot. Two of them can help prop up both the rotation and the bullpen.

Second – once-thru-the-order is a useful way of thinking about the issue. But it would be just as dumb to turn that into some obsessive rigidity as the current obsessions with 100-pitch limits and 1-inning max are. Rigidity is what makes it difficult to find/develop the talent needed to fill those roles. Flexibility – eg finding some of those multi-innings w pitchers who are still developing the repertoire to stretch out to twice-thru-the-order and then become starters — and other multi-innings with pitchers who are developing the mental side of their game to clamp down when things get more high-leverage to ultimately become the fireman/closer type. Open both those options and its clear that that role is a great entry into MLB for younger pitchers and probably sooner than the current system.

I think the fault of this multi inning thing is assuming rest of the pitcher needed is proportional to the innings pitched. More innings need more rest but this isn’t linear, you couldn’t throw 0.2 innings every day for example because warming up and throwing a few max effort pitches is a stress for the body too.

Imo there is a good reason why you still have the 1 inning or 5 plus innings dichotomy because there simply isnt a great rest schedule for 3 inning appearances that keep you fresh and still allow enough innings, I.e. the required rest after 3ip is closer to the 4 day rest of a starter (or at least 3 days rest which was starter rest till the 70s) than to a normal reliever schedule.

And even 2 inning stints work for some time but burn you out long term (or you need too much rest).

Thus I think it is still 1 inning with occasional 2 inning stints for top relievers. You can use them as a more flexible ace but stint length is still limited plus the pen ace roll is probably more stressful because there is less routine.

Imo sabermetrics writers don’t consider those physiological enough and focus too much on the single game. I mean there probably is a reason why smart guys like Epstein or luhnow still go pretty conventional.

Bullpens did become more diverse but the usage of multi inning stints is limited over a full season within the constraints of a baseball roster

I’m glad to hear that you’ve busted the myth of the LaRussa bullpen model. I am not a fan of these bloated bullpens and overspecialization. But I have to take issue with your reliance on the three-times-through-the-order dogma. That’s right – dogma – because that’s what it has become, Yes, its true that hitters can get a starting pitcher’s number after a couple of ABs but I don’t think it should be used in a Pavlovian, push-button fashion.

Its not hard to tell if a starting pitcher is losing his stuff or if the hitters are taking his measure. This is nothing new. But it should be based on what’s happening in THAT game not what you expect to happen based on statistics. If a pitcher is not tiring or losing his command then leave him in. Don’t fix what isn’t broken. As you acknowledge, the more pitchers you use in a game the higher probability that you will find the one who’s having a bad day. And it could be the first guy you bring in.

So, while I applaud your argument about developing more multi-inning relievers (where have you gone Dick Tidrow?) nothing can replace starting pitchers who can regularly give you length and by length I mean 7+ innings – not this 5-6 inning stuff. The fact they don’t anymore is a choice that’s been made not some law of nature.

I think the only solution to this is to put a hard limit on the size of pitching staffs. Manfred’s ridiculous 13-man limit should be reduced to 12 immediately and then reduced by one every two years until it reaches 10 – a number that every team found perfectly reasonable not so long ago. This would force teams to develop starter’s ability to produce length and to use their bullpens only when absolutely necessary.

Relief pitching is having far too much impact on the game these days. Relief pitchers are the most one-dimensional and least interesting of all baseball players. I wish the game would be turned back over to starting pitchers, positions players including an expanded bench instead of a parade of one-trick pony, one-innig specialists.

“Its not hard to tell if a starting pitcher is losing his stuff or if the hitters are taking his measure.”

Actually, various analyses have indicated that it’s a lot harder to figure this out than conventional wisdom thinks. This idea could be another fallacy – much like the fallacy that certain players are reliably “clutch” – that’s been debunked by statistical analysis.

Here is one such analysis of “dealing” vs. “non-dealing” starters by Mitchel Lichtman – https://mglbaseball.com/2014/10/20/dealing-or-dueling-whats-a-manager-to-do/

Lichtman’s conclusion:

“As I have been preaching for what seems like forever – and the data are in accordance – however a pitcher is pitching through X innings in a game, at least as measured by runs allowed, even at the extremes, has very little relevance with regard to how he is expected to pitch in subsequent innings. The best marker for whether to pull a pitcher or not seems to be pitch count.

If you want to know the most likely result, or the mean expected result at any point in the game, you should mostly ignore prior performance in that game and use a credible projection plus a fixed times through the order penalty, which is around .33 runs per 9 the 3rd time through, and another .33 the 4th time through. Of course the batters faced, park, weather, etc. will further dictate the absolute performance of the pitcher in question.

Keep in mind that I have not looked at a more granular approach to determining whether a pitcher has been pitching extremely well or getting shelled, such as hits, walks, strikeouts, and the like. It is possible that such an approach might yield a subset of pitching performance that indeed has some predictive value within a game. For now, however, you should be pretty convinced that run prevention alone during a game has little predictive value in terms of subsequent innings. Certainly a lot less than what most fans, managers, and other baseball insiders think.”

Yusmeiro petit has always struck me as the perfect example of a one-time-through-the-order pitcher who has had the bad fortune to play at a time when managers have no idea what to do with this kind of a pitcher. His bizarre invisiball delivery completely confuses most batters who haven’t seen him for a while. His performance in the 2014 postseason gives a pretty impressive idea of what he could do if used this way.