Smoothing the ‘80s and ‘90s (Part 4)

In our previous installments, we’ve explored the manner in which the stat lines of prominent players were affected by the changes in the offensive environment. Now it’s time for the best of the best.

Bear in mind that the stat lines that appear in black font are actuals, and the lines that appear in blue are adjusted. For our methodology, see the References and Resources section below.

The Trinity

Among the more intriguing careers, in a couple of ways. First, of course, is the “what might have been” aspect: what if he hadn’t been so brittle? And second is the larger point of just what a remarkable, singular talent Nomahh was at his best: there have been very, very few shortstops in history with a closely comparable offensive profile of free-swinging, high-contact, extreme-high-average, extra-base power … there’s Robin Yount, and, you know, Honus Wagner. That’s pretty much it. A very special player, at least for a few years.

Year Age AB R H 2B 3B HR RBI BB SO BA OBP SLG OPS 1996 22 86 10 20 2 3 4 15 4 13 .236 .267 .457 .724 1997 23 678 113 203 41 12 27 90 32 85 .299 .331 .515 .846 1998 24 598 102 189 35 8 32 113 30 58 .316 .349 .562 .911 1999 25 526 95 184 40 4 24 96 47 36 .350 .403 .581 .985 2000 26 523 96 191 48 3 19 89 56 46 .365 .427 .579 1.006 2001 27 83 13 24 3 0 4 8 7 9 .289 .344 .470 .814 2002 28 635 101 197 56 5 24 120 41 63 .310 .352 .528 .880 2003 29 658 120 198 37 13 28 105 39 61 .301 .340 .524 .864 2004 30 321 52 99 21 3 9 41 24 30 .308 .357 .477 .833 2005 31 230 28 65 12 0 9 30 12 24 .283 .318 .452 .770 2006 32 469 82 142 31 2 20 93 42 30 .303 .360 .505 .865 Career 4808 812 1513 326 54 200 799 334 456 .315 .359 .530 .889

Yeah, he isn’t the immortal the Big Apple media and fawning Yankeedom apparently believe him to be. And he almost certainly doesn’t deserve those Gold Gloves, and the Yankees should have moved him to third base (or second base, or center field) to accomodate A-Rod.

All true. But year in, year out, Jeter continues to demonstrate that he is one tremendous player, and will deserve his waltz into the Hall of Fame five years after his final game, like clockwork.

Year Age AB R H 2B 3B HR RBI BB SO BA OBP SLG OPS 1995 21 48 5 12 4 1 0 6 3 10 .244 .286 .368 .654 1996 22 577 96 178 24 6 9 72 44 95 .308 .357 .418 .775 1997 23 648 107 184 29 7 9 65 68 116 .284 .352 .394 .747 1998 24 620 117 197 24 8 17 78 52 110 .318 .371 .466 .837 1999 25 621 124 213 35 9 22 94 84 108 .343 .421 .534 .955 2000 26 587 110 195 29 4 14 67 63 92 .332 .397 .466 .863 2001 27 614 110 191 35 3 21 74 56 99 .311 .369 .480 .849 2002 28 644 124 191 26 0 18 75 73 114 .297 .368 .421 .789 2003 29 482 87 156 25 3 10 52 43 88 .324 .379 .450 .829 2004 30 643 111 188 44 1 23 78 46 99 .292 .340 .471 .811 2005 31 654 122 202 25 5 19 70 77 117 .309 .382 .450 .831 2006 32 623 118 214 39 3 14 97 69 102 .343 .409 .483 .892 Career 6760 1230 2120 338 52 176 828 677 1150 .314 .376 .457 .833

Top Ten List of Really, Really Idiotic Things:

10. The Umpires’ Union’s mass-resignation plan

9. The design of Candlestick Park

8. The typical guest on Dr. Phil

7. France’s plan to defeat the Nazis

6. New Coke

5. Trading Joe Nathan, Francisco Liriano, and Boof Bonser for A.J. Pierzynski

4. Believing the guy when he says that your friendship is what matters most to him

3. The Bush-Cheney-Rumsfeld Iraq strategy

2. Giving your bank account number to the representative of the Finance Minister of Nigeria

1. Booing A-Rod

Year Age AB R H 2B 3B HR RBI BB SO BA OBP SLG OPS 1994 18 54 4 11 0 0 0 2 3 19 .199 .238 .199 .437 1995 19 141 14 32 6 2 5 18 6 39 .227 .256 .394 .650 1996 20 595 130 209 51 1 33 113 54 97 .351 .405 .605 1.010 1997 21 582 92 171 38 3 21 78 38 92 .294 .337 .477 .813 1998 22 680 113 207 33 5 38 114 41 112 .304 .344 .536 .880 1999 23 498 101 139 24 0 38 102 51 101 .279 .346 .556 .902 2000 24 549 124 170 32 2 37 122 92 112 .310 .409 .579 .987 2001 25 632 133 201 34 1 52 135 75 131 .318 .390 .622 1.012 2002 26 624 125 187 27 2 57 142 87 122 .300 .385 .623 1.009 2003 27 607 124 181 30 6 47 118 87 126 .298 .386 .600 .986 2004 28 601 112 172 24 2 36 106 80 131 .286 .370 .512 .883 2005 29 605 124 194 29 1 48 130 91 139 .321 .409 .610 1.019 2006 30 572 113 166 26 1 35 121 90 139 .290 .387 .523 .909 Career 6739 1310 2039 353 27 446 1301 795 1360 .303 .376 .562 .938

Junior

He’s persevered through the long run of significant injuries to forge a career that falls short of all-time great, but just short. Griffey is certainly better, but in watching his story unfold it’s always struck me that we’re witnessing pretty much the second coming of Duke Snider: a glamorous star yet never seeming quite comfortable in the spotlight, big yet silkily graceful, handling center field with sparkling panache, delivering bombs with the gorgeous lefty swing, but doomed to an early decline by unshakeable leg trouble.

Year Age AB R H 2B 3B HR RBI BB SO BA OBP SLG OPS 1989 19 459 66 124 25 0 20 66 44 88 .271 .335 .459 .794 1990 20 603 99 185 31 7 28 87 64 86 .307 .373 .522 .895 1991 21 554 83 185 46 1 28 109 72 87 .334 .411 .573 .984 1992 22 571 90 180 43 4 35 112 44 71 .315 .365 .586 .951 1993 23 580 112 178 39 3 49 108 94 94 .307 .404 .640 1.044 1994 24 429 87 136 23 4 36 83 51 68 .317 .390 .643 1.033 1995 25 258 48 65 7 0 15 39 48 49 .252 .369 .457 .826 1996 26 540 115 160 25 2 44 129 72 97 .297 .379 .596 .975 1997 27 603 115 180 32 3 51 136 70 112 .298 .371 .614 .985 1998 28 628 111 175 31 3 51 135 70 112 .278 .351 .581 .931 1999 29 601 113 168 25 3 44 124 84 100 .279 .368 .548 .915 2000 30 516 92 137 21 3 36 109 86 109 .265 .371 .529 .899 2001 31 364 57 104 20 2 22 65 44 72 .286 .363 .533 .896 2002 32 197 17 52 8 0 8 23 28 39 .264 .356 .426 .782 2003 33 166 34 41 12 1 13 26 27 44 .247 .352 .566 .919 2004 34 300 49 76 18 0 20 60 44 67 .253 .349 .513 .862 2005 35 491 85 148 30 0 35 92 54 93 .301 .371 .576 .947 2006 36 428 62 108 19 0 27 72 39 78 .252 .315 .486 .801 Career 8289 1436 2403 453 37 563 1574 1035 1464 .290 .369 .557 .926

*98

Slammin’ Sammy’s overnight transformation at age 29 from a good slugger into a great one was quite unusual, no doubt, but it wasn’t entirely unprecedented. Through the years, a handful of other big-power hitters rather suddenly ratcheted themselves into the elite tier in mid-to-late-career: Roy Sievers comes to mind, as well as Frank Howard, and a pair of Baker Bowl-influenced old-timers, Gavvy Cravath and Cy Williams. And especially when considering the rather extended early-career struggles, Sosa’s career arc bears quite a bit of similarity to that of George Foster.

So reasonably comparable things had happened before, and steroid suspicion notwithstanding, it seems clear that particularly in Sosa’s case the element that generated his breakthrough wasn’t increased strength nearly so much as it was improved discipline: he somehow learned to generally lay off the breaking ball in the dirt. The late acquisition of that skill changed everything for Sosa, and to their dismay, the pitchers facing him. All of a sudden a reliable method of retiring Sosa no longer delivered the goods, and a highly dangerous hitter with a clearly exploitable weakness was now a highly dangerous hitter, period. One suspects that similar old-dog-new-trick stories are behind the improvements of guys like Sievers and Howard as well.

Certainly, by the late 1990s Sosa was massively strong, whether steroid-enhanced or not, and his great strength in concert with his improving strike zone judgment rendered Slammin’ Sammy a pitcher’s nightmare. “Improving” is the operative term, as after his breakthrough season of 1998 Sosa continued to improve, not peaking until 2001 at age 32. His subsequent decline was rapid, and it adds up to a career of dizzying extremes, in shape and in skill profile. Toss in the PED suspicion, and the corked-bat embarrassment for good measure, and we have a conglomeration that promises for a highly entertaining Hall of Fame debate.

Year Age AB R H 2B 3B HR RBI BB SO BA OBP SLG OPS 1989 20 185 29 49 9 0 5 14 11 50 .264 .305 .394 .700 1990 21 536 78 128 28 10 19 76 33 158 .239 .284 .438 .722 1991 22 318 42 66 11 1 13 36 14 104 .208 .242 .370 .612 1992 23 264 45 70 8 2 10 27 19 67 .266 .316 .427 .743 1993 24 597 91 155 26 5 36 92 37 139 .259 .303 .501 .804 1994 25 422 54 124 16 6 23 65 23 85 .294 .331 .523 .854 1995 26 560 82 147 16 3 33 110 53 124 .262 .326 .477 .803 1996 27 494 78 132 20 2 36 92 31 124 .267 .311 .536 .847 1997 28 637 83 156 29 4 33 110 41 162 .245 .291 .458 .749 1998 29 637 124 192 19 0 60 146 67 159 .302 .368 .613 .981 1999 30 620 105 175 23 2 57 130 72 159 .282 .356 .602 .958 2000 31 598 98 187 36 1 45 127 84 156 .313 .397 .604 1.001 2001 32 577 146 189 34 5 64 160 116 153 .328 .440 .737 1.177 2002 33 556 122 160 19 2 49 108 103 144 .288 .399 .594 .993 2003 34 517 99 144 22 0 40 103 62 143 .279 .356 .553 .909 2004 35 478 69 121 21 0 35 80 56 133 .253 .331 .517 .848 2005 36 380 39 84 15 1 14 45 39 84 .221 .294 .376 .670 Career 8377 1385 2280 351 45 572 1521 863 2143 .272 .340 .530 .870

Like Sosa, McGwire peaked late, but Big Mac’s late-career improvement wasn’t nearly as pronounced. Indeed, this exercise clearly illustrates that the impression of McGwire’s performance as having dipped into a trough following his great rookie year was, outside of his genuinely poor season of 1991, something of an illusion of the ’88-to-’92 scoring drought, and his revival beginning in 1995 was significantly amplified by the late-’90s offensive boom. McGwire was a better hitter in this thirties than he had been in his twenties, but not to such a strong degree as a superficial look at his stats might suggest.

Indeed what distinguishes the McGwire of his late-’90s heyday from his earlier career isn’t so much improved power as it is improved health (especially in comparison with the injury-decimated 1993-95) and improved plate discipline. Little mention ever seems to be made of it, but Big Mac drew significantly more walks (even controlling for intentional walks) in the second half of his career. Many hitters demonstrate improved strike zone judgment as they age, but McGwire’s improvement was especially large, and unquestionably explains a lot of his improved home run heroics: while Sosa transformed his plate discipline from terrible to decent, McGwire transformed his from good to great, and the better ability of both hitters to force pitchers to throw them strikes gave them better opportunities to go yard.

McGwire was a devastating offensive force in the late 1990s, but we see here that relative to the league around him, Cecil Fielder in 1990 had a slightly better year in terms of total home run output than McGwire in 1998. And this exercise indicates that Big Mac lost more home runs to the difficult conditions of 1988-1992 than he gained from the forgiving conditions of 1994-2000. As the McGwire Hall of Fame debate swirls around us, it’s interesting to contemplate if the scenario we see here had actually unfolded—Big Mac falls just short of tying Fielder’s single-season home run record, but hangs on to reach the 600-career-homer mark at the end—whether the degree of steroid controversy that’s focused upon Big Mac would have played out as it has, and whether his Hall of Fame election would be any more or less likely.

Year Age AB R H 2B 3B HR RBI BB SO BA OBP SLG OPS 1986 22 53 10 10 1 0 3 9 4 18 .189 .246 .377 .623 1987 23 557 97 161 28 4 49 118 71 131 .289 .369 .618 .987 1988 24 555 95 148 24 1 41 108 77 124 .267 .356 .535 .891 1989 25 494 81 117 19 0 42 103 84 99 .237 .348 .531 .879 1990 26 527 95 127 18 0 50 118 111 123 .241 .374 .559 .932 1991 27 486 67 100 24 0 28 82 94 123 .206 .335 .430 .765 1992 28 471 95 129 24 0 54 113 91 111 .275 .392 .668 1.060 1993 29 84 16 28 6 0 10 24 21 20 .331 .463 .758 1.222 1994 30 134 24 33 3 0 8 23 34 37 .246 .399 .450 .849 1995 31 314 69 84 12 0 35 83 81 71 .269 .418 .645 1.063 1996 32 419 96 128 20 0 47 104 107 104 .306 .447 .690 1.137 1997 33 536 79 144 25 0 53 113 93 148 .268 .376 .610 .986 1998 34 505 120 148 20 0 63 136 149 144 .292 .454 .709 1.163 1999 35 517 109 141 20 1 59 136 122 131 .272 .412 .657 1.068 2000 36 234 55 70 8 0 29 67 70 72 .299 .460 .703 1.163 2001 37 299 48 56 4 0 29 64 56 118 .187 .315 .492 .807 Career 6185 1156 1624 255 6 601 1401 1264 1573 .263 .388 .597 .985

The Unbeatable Four-Ace Hand

In one of the Abstracts of yore, Bill James outlined the terms of a debate that he titled “Pesky-Stuart.” The genesis of it was good-natured (or perhaps not so good-natured, I don’t know) arguments that were said to have been a frequent occurrence in the clubhouse of the Boston Red Sox of 1963-64, pitting their talkative manager, Johnny Pesky, against their even more talktative first baseman, Dick Stuart. Pesky had been a fine player in his day, and Stuart was a good one too, but their offensive profiles could hardly have been more different: Pesky was a high-average OBP specialist, devoid of power, while Stuart was a free swinger, not good at getting on base, but delivering outstanding power. The gist of the debate was Pesky’s insistence that it was getting on base, avoiding outs, that ensured offensive success, with Stuart retorting that it takes a mighty damn long sequence of scratch singles and walks to yield as many runs as just a few mighty extra-base clouts.

Of course, Pesky and Stuart were both right and both wrong, as James would point out; the best offenses feature neither strictly Peskys nor Stuarts, but instead a few of each, properly deployed in sequence: the surest way to score runs has always been to get some guys on and then drive them home. (And the very best hitters are neither Peskys nor Stuarts, but are instead those rare animals who excel both at getting on base and in driving others home.) The symbiotic relationship between OBP and SLG is essentially what James used to develop his foundational Runs Created statistic, and that interplay is at the heart of all sophisticated analysis and understanding of how teams score runs. Thus the Pesky-Stewart debate, while fun, is fundamentally irresolvable; at its essence it’s equivalent to debating whether a plant requires sunlight or water in order to grow.

In recent years I’ve sometimes encountered a different but somewhat related debate, which we might call “Pedro-Koufax.” The dynamic of this one goes something like this: Fan A, expressing awe at the staggeringly great rate stats (ERA, or ERA+, or WHIP or whatever) achieved by Pedro Martinez in his best years, asserts that Pedro might well have been the greatest pitcher of all time. Wait a minute, interjects Fan B; you can’t just look at rate stats, you have to also factor in workload, and when you do, you realize that, say, a Sandy Koufax, putting up amazingly good rate stats of his own, but in an innings-pitched workload about 50% greater than Pedro’s, was greater than Pedro.

Oh no, counters Fan A, not if you take league-and-park context into account. All well and good, responds Fan B, but a game still consumes nine innings and a season still consumes 162 games, and those innings and games left unpitched by Pedro have to be handled, once you complete the cascade, by the worst pitcher on the staff.

And so it goes. A relief pitcher variant of it is “Rivera–Gossage.” The point here isn’t whether the particular guy with better rate stats in fewer innings is better than his counterpart with not-as-great rate stats but more innings, but that the question is always relevant, even critical, to ask. Workload matters for pitchers, a lot. Unlike batters, who (assuming they’re regulars) are all going to accumulate their 600-or-so plate appearances over the course of a full season, the deployment of pitchers is far more varied and discretionary. And while it’s an unqualified good to get your best hitters up to the plate as frequently as possible, the far more physically demanding nature of the pitching task presents a very real risk-reward tradeoff for teams, between having their best pitchers on the mound as often as possible, against the exhaustion and injury risk of a heavy pitching workload.

Thus while it may well be possible to make a conclusive case of a particular pitcher having delivered more value than another, despite widely differing workloads, at its heart this debate is every bit as irresolvable as Pesky-Stuart. A pitcher’s effectiveness is crucial in assessing his value, of course, but so is his workload he delivers; the two issues are utterly inseparable. The trickiness of weighting one against the other, especially when comparing pitchers across eras, is something that makes the fan’s (or analyst’s, or Hall of Fame voter’s) assessment of the value of specific pitchers more challenging than that of specific batters, but it simply must be done. And for actual teams handling actual pitchers, the eternal dilemma of how-much-work-is-too-much is something that makes the management of pitching staffs an eternal headache.

Pedro serves as the ideal catalyst for the debate because he’s such an extreme case: no starter in the Hall of Fame has enjoyed nearly as restful a workload, but on the other hand, this guy has produced the all-time best career ERA+, by a mile. It may very well be the case that Pedro has been the most effective pitcher to ever fling a baseball, but the question of exactly where he stands up against others in terms of single-season and career value delivered is far more difficult to resolve.

In any case, his ERA+ of 285 achieved in 2000 has been surpassed in major league history only by Tim Keefe in, get this, 1880 (and Keefe did that in a season just about exactly half as long as a modern season, and worked just 105 innings). Pedro’s adjusted 2000 ERA of 1.62 that we see here would be the best ERA by any qualifier in the American League since Luis Tiant’s 1.60 in the extreme low-scoring year of 1968, and before that you’d have to go all the way back to Walter Johnson in 1919. And as we saw here, Pedro’s walk/strikeout ratio in league context rivals that of the very best ever, too.

But as we know, he’s long been rather fragile, and his struggles of 2006 may suggest that the end is near. We should take serious care to comprehend just what a monumentally special pitcher this guy has been.

Year Age G IP W L H HR BB SO ERA 1992 20 2 8 0 1 6 0 1 8 2.38 1993 21 65 107 10 5 75 5 56 122 2.68 1994 22 24 145 11 5 112 10 41 132 3.17 1995 23 30 195 14 10 153 19 61 162 3.26 1996 24 33 217 13 10 183 17 64 206 3.43 1997 25 31 241 17 8 153 15 62 283 1.76 1998 26 33 234 19 7 182 24 62 233 2.68 1999 27 31 213 23 4 155 8 34 291 1.92 2000 28 29 217 18 6 124 15 29 264 1.62 2001 29 18 117 7 3 84 5 25 163 2.39 2002 30 30 199 20 4 144 13 40 239 2.26 2003 31 29 187 14 4 147 7 47 206 2.22 2004 32 33 217 16 9 193 26 61 227 3.90 2005 33 31 217 15 8 159 19 47 208 2.82 2006 34 23 133 9 8 108 19 39 137 4.48 Career 442 2646 206 92 1980 202 669 2880 2.70

The Big Unit didn’t achieve his first full big league season until the age of 25, and struggled that year to a 7-13, 82 ERA+ result, not exactly portents of a long and successful run.

But then, The Big Unit established himself as a bona fide major leaguer. However, the level he achieved over his age-26-thru-age-28 seasons was as a little-better-than-league-average innings-eater, who racked up a ton of strikeouts but also yielded vastly too many walks. The daunting pitch-count accumulation didn’t bode well.

But then, The Big Unit suddenly demonstrated the ability to coordinate the far-flung moving parts in his 6-foot-10-inch delivery and control his exceptionally-high-velocity offerings. However, he was 29, and with more mileage on his tires than most 29-year-olds. It didn’t appear as though he’d enjoy an extended run of stardom.

But then, The Big Unit improved his control, and improved it some more, developing the capacity to paint with his slider as well as his fastball. He became, in his thirties, not just a star, but one of the elite aces in the game. Indeed he persevered through some significant injuries and just got better and better, putting together a run through his mid-to-late thirties that ranks with the best ever.

Now, well into his forties, The Big Unit appears to finally be nearing the end of the line. But then, with this guy, I wouldn’t be too sure.

Year Age G IP W L H HR BB SO ERA 1988 24 4 26 3 0 24 4 7 26 2.56 1989 25 29 161 7 13 152 17 97 137 5.09 1990 26 33 220 14 11 180 33 121 205 3.86 1991 27 33 201 13 10 156 19 154 241 4.20 1992 28 31 210 12 14 159 17 146 255 3.98 1993 29 35 255 19 8 183 24 97 317 3.33 1994 30 23 172 13 6 128 13 66 189 2.96 1995 31 30 214 18 2 154 11 60 273 2.30 1996 32 14 61 5 0 47 7 23 79 3.41 1997 33 30 213 20 4 143 18 71 270 2.12 1998 34 34 244 19 11 197 21 79 305 3.04 1999 35 35 272 17 9 201 27 64 338 2.30 2000 36 35 249 19 7 196 21 70 322 2.45 2001 37 35 250 21 6 181 19 71 372 2.49 2002 38 35 260 24 5 197 26 71 334 2.32 2003 39 18 114 6 8 125 16 27 125 4.26 2004 40 35 246 16 14 177 18 44 290 2.60 2005 41 34 226 17 8 207 32 47 211 3.79 2006 42 33 205 17 11 194 28 60 172 5.00 Career 556 3799 280 147 3002 371 1375 4461 3.19

With Pedro or the Big Unit, exactly why they were blowing opposing lineups away was blatantly obvious: their stuff was just overpowering, unhittable. But Maddux never overpowered anyone in his life. That his combination of magnificent control, smarts, and competitive intensity would make him an excellent pitcher is one thing, but at his peak Maddux wasn’t merely excellent, he was bordering on perfect. It was just weird that major league hitters could be made that helpless by those pitches.

Year Age G IP W L H HR BB SO ERA 1986 20 6 31 2 4 44 3 11 20 5.52 1987 21 30 156 6 14 181 17 74 101 5.61 1988 22 34 249 18 8 238 17 82 148 3.36 1989 23 35 238 19 12 230 17 83 143 3.12 1990 24 35 237 15 15 251 14 72 152 3.65 1991 25 37 263 15 11 240 23 67 209 3.54 1992 26 35 268 20 11 208 9 71 210 2.30 1993 27 36 267 20 10 226 15 51 203 2.43 1994 28 25 202 16 6 146 4 28 145 1.45 1995 29 28 210 19 2 143 7 21 168 1.51 1996 30 35 245 15 11 218 10 26 160 2.52 1997 31 33 233 19 4 194 8 18 164 2.04 1998 32 34 251 18 9 195 12 41 189 2.06 1999 33 33 219 19 9 250 15 34 126 3.31 2000 34 35 249 19 9 218 17 39 176 2.78 2001 35 34 233 17 11 220 20 27 173 3.05 2002 36 34 199 16 6 194 14 45 118 2.62 2003 37 36 218 16 11 225 24 33 124 3.96 2004 38 33 213 16 11 218 35 33 151 4.02 2005 39 35 225 13 15 239 29 36 136 4.24 2006 40 34 210 15 14 219 20 37 117 4.20 Career 677 4616 333 203 4298 329 929 3133 3.06

The Rocket might not be the best pitcher in the history of the game, but if he isn’t, he’s very close. No serious consideration of the question can fail to prominently include him.

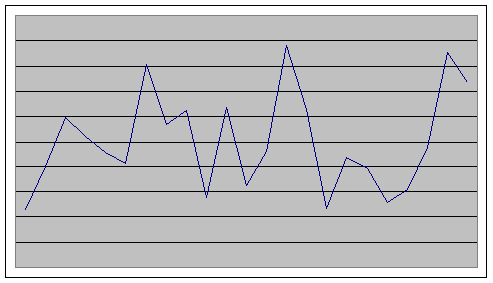

Given that, the strange thing about Clemens’ career is its complete lack of an arc. It’s as though all the individual season stat lines were tossed into a barrel and then selected one by one in random order. For instance, check out this zig-zagging line:

Know what that is? It’s The Rocket’s ERA+, by season. There’s essentially no pattern at all; Clemens has never really had a peak, or perhaps it makes more sense to say he’s had numerous interchangeable peaks, as well as a few valleys. It’s an odd sort of inconsistency, that wouldn’t seem to be associated with such a phenomenally great player, but it is.

Year Age G IP W L H HR BB SO ERA 1984 21 21 133 9 4 146 13 29 126 4.32 1985 22 15 98 7 5 83 5 37 74 3.29 1986 23 33 254 24 4 179 21 67 238 2.48 1987 24 36 282 20 9 248 19 83 256 2.97 1988 25 35 264 18 12 225 22 63 307 3.09 1989 26 35 253 17 11 223 26 94 243 3.31 1990 27 31 228 21 6 200 9 55 221 2.04 1991 28 35 271 18 10 227 19 66 255 2.77 1992 29 32 247 18 11 210 14 63 220 2.55 1993 30 29 192 11 14 174 19 66 165 4.59 1994 31 24 171 9 7 120 14 65 156 2.65 1995 32 23 140 10 5 137 14 55 123 3.88 1996 33 34 243 10 13 210 17 97 239 3.37 1997 34 34 264 21 7 198 8 63 271 1.90 1998 35 33 235 20 6 164 10 81 252 2.46 1999 36 30 188 14 10 180 18 83 151 4.27 2000 37 32 204 13 8 179 24 77 175 3.43 2001 38 33 220 20 3 205 19 72 213 3.51 2002 39 29 180 13 6 172 18 63 192 4.35 2003 40 33 212 17 9 199 24 58 190 3.91 2004 41 33 214 18 4 169 15 79 218 2.98 2005 42 32 211 13 8 151 11 62 185 1.87 2006 43 19 113 7 6 89 7 29 102 2.30 Career 691 4818 348 178 4086 365 1506 4569 3.08

Mr. Bonds

That OPS figure there in 1992 would be the highest anyone had posted since Ted Williams in 1957, and the highest in the National League since Hack Wilson in 1930. And then, of course, Bonds would surpass it in ’93. This exercise shaves 25 homers from Bonds’s total in the 1994-2000 period, but gives back an additional 42 for 1988-93; overall it’s clear that Bonds was hurt more by the low-offense conditions of the early part of his career than helped by those of the high-offense middle part.

But of course, what seems to have transfixed everyone’s attention is Bonds’s performance within the middle-range conditions of the last part of his career. The magnitude of the late-career power-and-average peak is distinctly clarified by this exercise. However, before immediately leaping to the frequently-heard conclusion along the lines of “this clearly demonstrates how dramatically steroid usage enhances baseball performance,” it’s prudent to contemplate a few points:

– The general assumption is that Bonds began using PEDs following the 1998 season—a full two years before his spike in peformance began in 2001.

– MLB began its first random steroid-testing program in 2004, a season in which the 39-year-old Bonds never flunked a drug test—and he hit just about exactly as well as he had in 2001-2002.

– Based on the profile of players who have failed drug tests in 2004 and since, it seems likely that more than a few of the pitchers Bonds was facing post-1998 were PED users, and probably at a higher proportion in that period (at least through 2003) than that of earlier in his career.

– Also based on the profile of players who’ve failed drug tests, significant or even noticeable performance spikes aren’t typical career features at all.

None of these points mean that Bonds hasn’t used steroids; personally I’ve never doubted that he has. But they do suggest:

– Bonds has been hardly alone and perhaps not even unusual within MLB as a steroid user.

– His spike in performance has been anything but typical of steroid users, and thus almost certainly not solely a function of steroid use.

– His continuing maximal performance even under the drug testing protocol of 2004 further undercuts the certainty of the spike being entirely steroid-caused, and/or it should cause one to seriously question the efficacy of testing at curbing PED usage.

At any rate, this much is certain: all things considered, this guy is, if not the very best, then at least among the tiny handful of very best baseball players the world has yet seen.

Year Age AB R H 2B 3B HR RBI BB SO BA OBP SLG OPS 1986 21 413 72 92 26 3 16 48 65 102 .223 .328 .416 .745 1987 22 551 99 144 34 9 25 59 54 88 .261 .327 .492 .819 1988 23 543 106 157 33 5 31 63 73 87 .290 .374 .538 .912 1989 24 585 104 149 37 6 24 63 94 98 .255 .358 .464 .822 1990 25 525 113 162 35 3 42 124 94 88 .308 .413 .628 1.041 1991 26 515 103 154 31 5 32 126 108 77 .299 .421 .565 .986 1992 27 478 119 152 39 5 44 112 128 73 .318 .463 .695 1.158 1993 28 537 128 179 39 4 50 122 124 81 .334 .459 .703 1.161 1994 29 387 82 118 17 1 34 75 68 40 .306 .409 .615 1.024 1995 30 502 101 145 28 7 30 96 110 77 .288 .417 .553 .970 1996 31 512 113 154 25 3 38 119 139 71 .301 .450 .586 1.036 1997 32 527 113 150 25 5 36 93 133 81 .285 .429 .558 .987 1998 33 547 111 162 41 7 34 113 120 85 .296 .422 .583 1.005 1999 34 352 84 90 19 2 31 77 67 58 .256 .375 .584 .959 2000 35 476 119 143 26 4 44 98 108 71 .300 .429 .653 1.082 2001 36 476 129 156 32 2 73 137 177 93 .328 .510 .863 1.373 2002 37 403 117 149 31 2 46 110 198 47 .370 .577 .799 1.376 2003 38 390 111 133 22 1 45 90 148 58 .341 .522 .749 1.271 2004 39 373 129 135 27 3 45 101 232 41 .362 .607 .812 1.419 2005 40 42 8 12 1 0 5 10 9 6 .286 .412 .667 1.078 2006 41 367 74 99 23 0 26 77 115 51 .270 .444 .545 .989 Career 9503 2134 2837 592 79 751 1912 2364 1472 .299 .438 .614 1.053

References & Resources

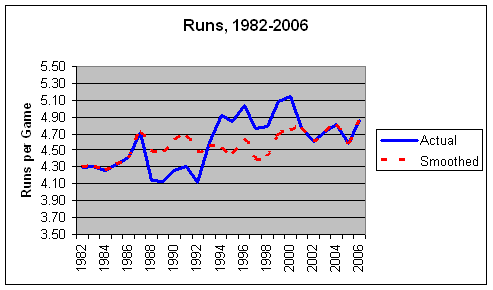

In order to modify the actual stats into a shape fitting this smoothed line:

We used an approach similar to the approach we used in several past such exercises, beginning with the overall aggregate rate of the primary offensive events for the entire 1982-2006 period: runs, hits, doubles, triples, home runs, walks, and strikeouts. We then adjusted the rates for each season from 1988-1992 to bring the aggregate total for that period to equal that of 1982-2006, also for 1993, and also for 1994-2000. The specific multipliers employed are:

1988-92:

Runs: 1.087

Hits: 1.035

Doubles: 1.095

Triples: 1.012

Home Runs: 1.281

Walks: 1.011

Strikeouts: 1.056

1993:

Runs: 0.992

Hits: 0.992

Doubles: 1.023

Triples: 1.002

Home Runs: 1.097

Walks: 0.982

Strikeouts: 1.028

1994-2000:

Runs: 0.923

Hits: 0.971

Doubles: 0.943

Triples: 1.053

Home Runs: 0.906

Walks: 0.919

Strikeouts: 0.928

An impact of a change in the rate of hits is a change in at-bats, of course. I use a simple method to change at-bats: every batter’s at-bats are increased or decreased by his number of increased or decreased hits. Outs are constant, of course, and I assume as well a constant rate of double plays and baserunning outs—probably not exactly proper assumptions, but close enough for our purposes.