A History of Defunct Team Nicknames

The Brooklyn Bridegrooms have one of the best defunct team nicknames. (via Public Domain)

To understand the early nicknaming rituals in baseball is to understand two things: the long-gone power possessed by sportswriters of the time, and the exercise of identification by variously colored stockings.

Indeed, nicknames for the first handful of decades in major league baseball were just that—informal, un-trademarked, and usually dreamed up by the cigar-toting scribes of the day.

Every team was officially recognized, in some order, simply by its league and its city. For example The American League Baseball Club in New York. The Brooklyn National League Baseball Club. The American League Baseball Club of Chicago.

A stock certificate for the “American League Base Ball Club of Chicago,” also known as the Chicago White Sox. In the early days of baseball, the official name of a team simply included its league and city.

This system was, of course, horribly unimaginative and financially shortsighted, as far as marketing and merch-pushing went. Most of the 16 major league teams in the early 20th century didn’t solidify their nicknames until the end of the Deadball era in the early 1920s.

So, the nicknaming was often left up to the sportswriters, which was either a horrible mistake or a great opportunity for wordplay, depending on your level of generosity. Some nicknames were clever. Some were cringe-y. Some were one-offs used on a whim: One Boston Globe write-up from 1888 refers in the same story to Pittsburgh as both the “Burgers” and the “Smoky City men,” two names that appear to have had no staying power or relevance.

But the recurring ones that bubbled up from the pages of the dailies and into a city’s zeitgeist were generally part of the conversation at home and in the stands, said baseball historian and author Thomas W. Gilbert during a recent interview with The Hardball Times.

“Sometimes what gets in a reference book doesn’t reflect reality, but I think most of the time it does. You’ll find with a lot of these, they were in the cultural soup,” he said.

Oftentimes, the colloquial naming was left to the shade of whichever hosiery the local nine chose to play in. The pre-Braves were the Red Stockings. The pre-Cubs were the White Stockings. The pre-Cardinals were the Brown Stockings, a name the St. Louis Browns would later use themselves.

Some franchises were downright adventurous—the Dodgers toyed with at least six names before landing on the Dodgers—while others, like the Tigers, found what they liked and never deviated, remaining the Tigers since their inception in 1901.

Spread among the 16 franchises still around today, there are more than two dozen defunct nicknames that once dotted the sports pages.

With help from historians and baseball-reference.com, here they are, counted down from 25 in no particular order, and (almost all) explained.

But first, a few caveats:

- Baseball-reference.com lists the Indians as being named the Blues and Bronchos for one season each, in 1901 and 1902, respectively, but a search through newspapers.com showed no evidence that either name was used with any regularity, if at all, so those two were left out.

- It would be impossible to say with certainty that every recognized informal nickname was included in this list. If there’s any I’ve missed, feel free to reach out.

- Because many names were informal, there was likely a good deal of overlap; the years provided may be more in the ballpark than an exact pinpoint.

- Many of these explanations were provided with Gilbert’s help.

The teams who went by socks

The early obsession in baseball with stockings was birthed by practicality and individualism. It was a way to be remembered.

“If you think about baseball in the 19th century, when there’s no TV, when you’re in the stands, you’re distant from the action, it’s the most distinguishing feature on the uniform,” Gilbert said.

“If you go all the way back to the beginning of baseball, right, the most famous alleged first professional team—the Cincinnati Red Stockings, 1869-70—the stocking was their brand, their trademark. It was a flashy innovation at the time that has had a lasting impact.”

(Those original Red Stockings then moved to Boston, and later became the Braves, giving them the best claim to being the original Red Stockings.)

The other laundry-inspired old nicknames:

25. The Boston Red Stockings (1876-1882), now the Atlanta Braves

24. The Chicago White Stockings (1876-1889), now the Chicago Cubs

23. The St. Louis Brown Stockings (1882), shortened to the Browns (1883-1898), now the St. Louis Cardinals

22. The Brooklyn Grays (1885-1887), now the Los Angeles Dodgers

Several of those names also helped in naming different American League franchises in the same city that came along in the early 20th century.

“Part of their marketing idea was to revive the traditional names that had been dropped by the National League teams,” Gilbert said. “So the Cubs were once called the White Stockings and they had dropped that, so the Chicago American team took the White Stockings. Same thing happened in Boston.”

That explains both the White Sox and the Red Sox, plus the second St. Louis franchise:

21. The St. Louis Browns (1902-1954), now the Baltimore Orioles

The mid-life crises

20. The Boston Bees (1936-1940), now the Atlanta Braves

After 23 seasons as the Braves and coming off a 38-win 1935, the Boston National League team decided it was time for a rebranding.

The Boston papers held a naming contest, and the Bees won. According to rumor, Boston Braves Historical Association president Bob Brady told me in an interview, that was because it was short, sweet, and easy to fit in a big headline.

“It was a very unpopular decision among National League baseball fans,” Brady said.

The Bees were either bad or mediocre for five seasons before finally settling down with the Braves.

19. The Cincinnati Redlegs (1953-1958), now the Cincinnati Reds

In 1953, during the height of McCarthyism and the Red Scare, the Reds officially changed their name to the Redlegs to avoid Russian and communist analogies.

Baseball: sticking to sports since the 1950s.

Ancient resemblance

18. The New York Gothams (1883-1884), now the San Francisco Giants

17. The Brooklyn Atlantics (1884), now the Los Angeles Dodgers

Both of these names were successors—in name only—to two ancient pioneering New York area baseball clubs of the mid-1800s.

Regional nods

16. The Boston Beaneaters (1883-1906), now the Atlanta Braves

The Beaneaters can be explained through the obvious connection between Boston and baked legumes, though it was a casual enough moniker that the pre-Red Sox were also referred to as the Beaneaters from time to time.

15. The Milwaukee Brewers (1901), now the Baltimore Orioles

That’s right! Before the 1969 Seattle Pilots moved to Milwaukee and became the Brewers in 1970, there was a beer-inspired American League team under the same name for one season in 1901, before they moved to St. Louis and became the Browns.

There wasn’t one moment or quip to pinpoint the origin, but the name has an obvious association with Milwaukee’s long history of beer-making.

14. The Philadelphia Quakers (1883-1899), now the Phillies

Same as the Brewers: an obvious regional association without an exact origin.

13. The Washington Senators (1901-1960), now the Minnesota Twins

Beyond the regional association, what was interesting about this version of the Senators is that people still aren’t exactly sure if they were called the Senators or the Nationals.

The Washington Post would freely use either name. Baseball cards sometimes listed the team as the Nationals and sometimes the Senators.

A frontrunner didn’t truly emerge until 1956 when PR man Charlie Brotman was tasked with brainstorming the design for the 1957 yearbook. Given a choice between the two names, he went with the Senators because it offered more artistic freedom.

Upper management

12. The Brooklyn Robins (1914-1931), now the Los Angeles Dodgers

Longtime manager Wilbert Robinson, who managed Brooklyn from 1914 to 1931, was in the cultural zeitgeist enough to inspire this name.

11. The Boston Doves (1907-1910), now the Atlanta Braves

The Dovey brothers, George and John, owned the Braves from 1907-1910.

10. The Boston Rustlers (1911), now the Atlanta Braves

The Rustlers didn’t do much rustling in 1911. Or winning: In the lone season playing under the name inspired by new owner William Russell, the pre-Braves went 44-107, drawing the witty ire of Harold Kaese, Boston scribe and noted Ted Williams foe, who wrote, “A squirrel on a treadmill couldn’t have produced more action with less progress than the Boston Nationals of 1911.”

That line also shows the casual nature of early nicknames. Simply calling them the Boston Nationals was good enough.

Anyway, all that losing couldn’t have been good for Russell, who died in November 1912 of a heart attack.

9. The Chicago Orphans (1898-1902), now the Cubs

What do you call a team when its best player and manager, Adrian “Cap” Anson, leaves the club? If you’re a sportswriter in the fading years of the 19th century, you call that team the Orphans.

(Anson played 27 consecutive professional seasons, according to baseball-reference.com, and racked up 94.3 WAR for his career, which would be a fun exercise to explain to a baseball fan of that time.)

8. The Cleveland Naps (1903-1914), now the Indians

No, the prehistoric Indians weren’t a tired bunch, though that didn’t stop the press from having some fun with the name: “The Cleveland Naps awoke from their peaceful dreams Tuesday afternoon,” wrote the Akron Beacon Journal in a September 1905 sports section.

The Naps were inspired by Napoleon “Nap” Lajoie, the great second baseman who player-managed the club from 1905-09. Apropos of absolutely something, Lajoie hit .426 with the Philadelphia Athletics in 1901, which is a good start if you aspire to have sportswriters nickname a team after you.

The names that transcend categories

7. The New York Highlanders (1903-1912), now the Yankees

From 1903 to 1912, New York played in Washington Heights, in northern Manhattan, at Hilltop Park, which inspired the Highlanders.

The team would sometimes be called Gordon’s Highlanders in the papers, after team president and political personality Joseph Gordon, a reference to an infantry regiment of the British Army–which, as Gilbert told me, didn’t sit well with the team’s Irish fan base.

“It was sort of like calling a team in Saigon the Green Berets,” Gilbert said. “Some of the fans started calling them the Yankee Highlanders, as a way of saying: not British.”

6. The Alleghanys (sometimes the Alleghenys, 1882-1890), now the Pirates

The Pirates are named as such because, in 1891, they coaxed Lou Bierbauer from the Philadelphia Athletics, a move that caused much uproar from the A’s, who accused Pittsburgh of acting like pirates.

Before that, starting in 1882 in the American Association, the Pirates were referred to in newspapers as the Alleghany Club or the Alleghany Base Ball Club because they played in Alleghany City, once a separate municipality that was annexed by Pittsburgh in 1907.

And so, the Alleghanys nickname came with the territory. It was an offshoot of the tradition of the day to sometimes pluralize the city in which the team played, like, for example, the long-gone Worcester Worcesters.

5. The Chicago Colts (1890-1897), now the Cubs

A colt is young and fast, and so, too, apparently, were the pre-Cubs in the eyes of the press during the final decade of the 1800s.

4. The Boston Americans (1901-1907), now the Red Sox

This was less a nickname and more a way of distinguishing the future Red Sox from the National League team in Boston, though it was the closest thing to a moniker for the American League team until it picked up its current name.

(And, as Bill Nowlin debunks in this article, they were certainly never called the Pilgrims.)

3. The Brooklyn Bridegrooms (1888-1898), now the Los Angeles Dodgers

How did several of Brooklyn’s players spend their offseason? Getting married. And there you have it.

2. The Brooklyn Superbas (1899-1910), now the Los Angeles Dodgers

When vaudeville ruled the entertainment world, there was a popular group in Brooklyn named Hanlon’s Superbas. In 1899, Ned Hanlon took over as manager of the Brooklyn team. The press linked the two, despite Hanlon’s non-relation to the vaudeville group—and their own better judgment.

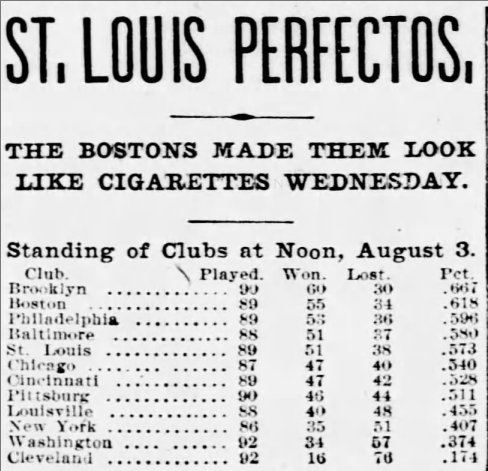

1. The St. Louis Perfectos (1899), now the St. Louis Cardinals

This last one is both interesting and frustrating: a rabbit hole of research that yields plenty of clues without one solid answer.

The Cardinals, whose classic name predates even the bird, went by this name for what seems like one season in 1899, after Cleveland Spiders owners Frank and Stanley Robison purchased the franchise, then known as the Browns or Brown Stockings.

Plenty of sources point toward Frank coming up with the name himself. The answer as to why likely falls in the connotation of the name.

Gilbert, in a follow-up email, wrote of the name: “I think that it is likely that the St. L club promoted the name ‘Perfectos’ because the name suggested quality and class. A perfecto cigar was an expensive rich man’s smoke. Note that other commercial products used the name in the same way. There were racehorses named perfecto.”

A headline from an August, 1899 edition of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch declaring the St. Louis Perfectos were made to “look like cigarettes” during a regular season game against Boston, suggesting a correlation between the name Perfectos and an identically named type of cigar.

There are hints of a cigar connection scattered throughout newspapers.

In a May 1899 edition of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch: “This patterning the ball teams after cigar signs is funny. Now that the Brooklyns have attached to themselves the name of ‘Superbas,’ the St. Louis have been styled the Perfectos.”

In an August edition of the same paper in the same year, after an uninspiring loss: “The Bostons made them look like cigarettes Wednesday.”

The obvious insinuation is that the team usually presents itself as high-class, like a cigar, or a Perfecto.

It is also possible that Frank Robison was hoping to convey a certain level of class with his new team in St. Louis, given the “rowdy” nature of his team in Cleveland. So inclined to cause a ruckus were the Spiders that the Post-Dispatch reported in March of 1898, in a style only a sportswriter of the 19th century could, that Robison had agreed to tone down the “rowdyism” for the upcoming season:

President Frank de H. Robison and (Cleveland Spiders) Manager Patsy Tebeau had a long talk this evening concerning the team’s behavior during the coming season, and the respect that is to be paid to the rule adopted at St. Louis to do away with rowdyism on the diamond. The result is that the players will be instructed to hold both tempers and tongues at all cost and it is not only dollars to doughnuts but dollars to the holes in doughnuts that no Cleveland man will require the services of the tribunal that is to sit upon cases where players are accused of rowdyism.

Go ahead—read that a few more times and see if it starts to make any more sense.

***

A lot of this research showed how innocent and non-corporate professional baseball was in its first handful of decades.

It’s fun to think of major league baseball when these names were, in Gilbert’s words, part of the day’s “cultural soup”–a deli conversation in Crown Heights over how the Bridegrooms did against the Colts in Chicago the night before, or a friendly argument in a Boston trolley over who would be the better team that year: the Americans or the Nationals.

In modern professional baseball, the Cape Cod League has been forced to stop using MLB nicknames for copyrighting purposes. Back then, for better or worse, it was simple: May the best sportswriter quip win.

“Aren’t you glad they don’t have that power anymore?” Gilbert said, laughing.

References & Resources

Baseball-Reference.com

Levitt, Amy. “Ever Wonder How the Cardinals Got Their Name?” Riverfront Times, October 21, 2011.

Newspapers.com

Nowlin, Bill. “The Boston Pilgrims Never Existed.” Baseball Almanac.

Schoenfield, David. “When the Reds Became Redlegs.” ESPN, April 9, 2015.

Excellent, entertaining article–but there’ s a glitch in No. 20 (Boston Bees). By 1936, the Babe was come and gone in Boston. He was enticed there by Judge Emil Fuchs in 1935, when the NL team was still known the Braves. Babe lasted until early June 1935 before he retired. About a week earlier he had his greatest moment as a Boston Brave with three home runs at Forbes Field in Pittsburgh. Then came the Bees . . .

Yep, you’re right. I’ll get that updated.

I realize you stuck to teams that are still around, but I’m not sure I have ever heard the story behind the Cleveland Spiders name.

Same here. Did a little bit of looking into them and found nothing on the name.

I came across this reference on the Spiders Wikipedia page

https://case.edu/ech/articles/c/cleveland-spiders

It seems the Spiders nickname is a reference to some skinny players.

The author found nothing, and you immediately found something on wikipedia? Ouch. Or maybe the author doesn’t trust wikipedia.

Cleveland adopted a nearly all-black uniform in 1889, the first season in which they were called spiders. Several teams adopted similar uniform styles that year, and that style of uniform were generally called “Nadjys”, after a play in which several women famously danced in black tights. Two years later, a newspaper article claimed that Cleveland had been called “Spiders” when they adopted the Nadjy uniform style. Several players were said to have been skinny, and they looked like spiders in their black, tight uniforms.

https://www.threadsofourgame.com/1889-cleveland/

Interesting. Thanks for that.

Brooklyn Bridegrooms is a pretty cool name. I wonder if there is a high school where the boy’s teams are the bridegrooms, and the girls teams are the brides?

“Bridegroom” is one of my least favorite words, as it sounds silly to say, “And the bride and bridegroom ran gleefully out of the church.” Why not just say “groom”? But in the context of Brooklyn Bridegrooms, I think it sounds better.

Probably the term bridegroom was used to distinguish the newly-married young man from the boy who grooms the horses.

You missed my personal favorite, the Pittsburgh “Smoked Italians”; a regular, if not common, name used from mid-1880 into the 1890s.

Amazing. It’s like the silly MiLB names today are a call-back to those days.