Against the trend, the Dodgers continue spending

Earlier in the week, the Dodgers signed Clayton Kershaw to a seven-year, $215 million contract that covers his final year of arbitration and six seasons of free agency. Kershaw can opt out of the contract after after the 2018 season, headed into his age-31 season.

The deal obviously is massive, and there has been plenty of analysis on the topic. It’s the largest contract ever signed by a pitcher, and he’ll temporarily be paid the highest average annual value of any player in baseball history.

The opt-out clause recognizes that the Dodgers believe he is worth even more than this contract. Alex Rodriguez and CC Sabathia have shown how valuable the opt-out can be; they both cashed in on their opt-outs shortly before showing signs of decline. Others like Vernon Wells demonstrate the risk clubs shoulder by including the opt-out.

Certainly, there is an upside to opt-outs, as a disciplined club (apparently not the Yankees) can let the player walk away without paying the final few seasons. For more on the opt-out component, including some small-sample evidence that teams should avoid paying for the second contract, I recommend this article by Dave Cameron.

The Dodgers were already in luxury tax-penalty land, so Kershaw’s contract represents an additional financial commitment. Unlike the Yankees, who have been dieting for several seasons in the hopes of reducing their tax burden, the Dodgers appear to be unapologetic about their free spending. Perhaps their massive TV deal has something to do with it. That deal, which is expected to be worth an average of $340 million per season, begins in 2014.

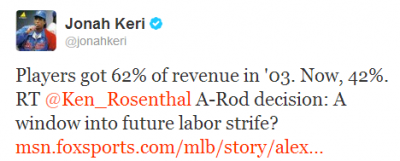

The announcement of Kershaw’s mega-deal coincided with this A-Rod related tweet from Jonah Keri:

With nine-figure contracts skyrocketing throughout baseball, it’s surprising that the players’ share of the revenue pie has declined so precipitously. It makes sense, though. A lot of new revenue has flooded baseball in recent years, and it could take some time before a new equilibrium is reached.

TV money used to be a game dominated by the Yankees’ YES network, but now the Dodgers are the big fish, and the Rangers, Mariners, Phillies and Angels have joined the high-stakes club. Based on the chart at the end of this article by Wendy Thurm, those five teams may average higher yearly earnings from their TV deals than the Yankees.

The chart in that article also shows the increasingly have-and-have-not nature of these TV deals. While they are subject to revenue sharing, the beneficiaries still, well, benefit. Revenue sharing currently calls for all teams to pool 31 percent of their local revenue, which is then divided into 30 equal slices. So the TV behemoths lose several million dollars, yet they retain a massive financial advantage.

A new system currently being phased in will disqualify the 15 teams in the largest markets from receiving revenue sharing, but that likely will create other imbalances. Additionally, revenue from an equity stake is not taxed, so clubs can effectively hide some of their revenue. However, it’s quite possible that owners will pocket those earnings.

Major League Baseball has been incredibly successful at cutting costs in recent seasons. Teams now have to semi-adhere to draft pick slotting set by the commissioner’s office, and there is also a limit on international spending. Teams can exceed their various pools and allocations, but they will be subjected to penalties.

Meanwhile, the luxury tax was given real teeth, to the point where most teams (not the Dodgers) appear to be looking at it as an actual cap. Even Japan’s Nippon Professional Baseball (NPB) agreed to a seemingly one-sided new posting arrangement, although it’s unclear if this will reduce or increase the cost of Japanese players.

Some speculate that the owners will turn their attention to controlling major league contracts next. As the line of thought goes, the players let them have Austria and Belgium uncontested, so now the owners want France and England. Of course, that is the one area where the MLBPA has shown a willingness in the past to fight. The player’s union is in the relatively inexperienced care of Tony Clark, so the owners may hope to steamroll the new regime on a firmer luxury tax or even a cap. That’s not likely to work.

Instead, look for the players to demand more compensation. The current arrangement expires after the 2016 season, so we probably won’t hear much about this topic for at least another year or two. Since baseball is raking in such large quantities of money, more than a few owners will go green at the gills when confronted with a possible labor stoppage. If the two parties are looking for a fair and equitable solution, perhaps it finally is time to do away with the reserve clause or take other steps to improve early-career compensation.

Depending on how this brewing battle shakes out, Kershaw’s mega-deal and other large, long-term commitments could look team-friendly as early as 2017.

When fans complain about players being overpaid, they should look at the revenue that baseball is raking in, albeit unequally, with their being large disparities between teams. Moreover, many teams are playing in tax-subsidized stadiums and, despite this, are permitted to keep most of the revenue these stadiums generate. It’s ok for owners to try to make money, but please don’t cry crocodile tears over how much players make.

You don’t shoulder risk by including the opt-out clause. You could actually consider it a risk mitigant. Essentially Kershaw has traded a lower AAV in exchange for the optionality to get out of the deal. So you’re paying Kershaw less in the first five years than what you otherwise would have paid him had there been no opt-out clause.

Marc, it depends on your point of view: players salaries as a percentage of baseball revenue, or players salaries compared to what the little folks in the stands make. The fact is, the money that pours into professional sports is beyond the comprehension of most everyday mortals. The lowest-paid scrub on an MLB roster makes far more than your “Average Joe”. Besides, I would bet dollars to donuts that fans’ anger has less to do with the amounts of $$ per se, and more to do with a perceived sense of player entitlement. (This is where agents like Scott Boras do their clients a disservice, making it sound like that $20 mill/year offer is somehow offensive . . . )

Mando3b,

I don’t disagree that many current players have a sense of entitlement that is infuriating. It’s quite annoying to hear Albert Pujols complain that offering him only $15-20 mil/yr. is “disrespectful.” A lot of players have no sense of perspective.

But the fact is, the owners often play on this resentment. Teams only pay what they can afford and what makes sense financially. (Although, like any other business, they may miscalculate.)Scott Boras, as annoying as he often is, is not the reason that players make so much money and, really, no one is putting a gun to the owners’ heads to pay. The owners, especially in smaller markets, often make it sound as if they are paupers and these greedy players are ruining the game. And they certainly try to imply that large salaries cause higher ticket prices when, in fact, ticket prices are largely a factor of teams being effective monopolies and facing little competition. (And, in any event, baseball ticket prices are much lower than in other sports.) I don’t blame the owners for this; they should charge what the market will bear. But don’t blame the players for this.

While I agree that many players have an annoying sense of entitlement, I think the reason fans get upset at players salaries is simple: they are reported, ad nauseam, in the media. Nobody ever talks about how much owners make, and it’s often difficult, if not impossible, to even figure that out. There is no hot-stove season for owners.

That said, if pro sports are going to rake in grotesque sums of money, I’d rather more of it go to the guys fans are actually paying to see. Especially considering that owners have a habit of swindling taxpayers.

I keep wondering if all these cable money gravy train will soon burst the day other internet technologies will be good enough, while overpriced cable and satellite deals will cause lots of people to cut off cable.

The only reason I have cable is because my apartment complex forces us to pay for it as part of our services bundle. It’s hooked up to a TV that I keep for classic video games, but I never turn it on.

One of the reasons the cable money is there is that live sports is one of the few things that people are still willing to pay for. So it’s a revenue cow for the cable operators. Unless cable simply dries up entirely, the baseball deals, I think, are likely to remain. Even if the internet technologies take over, I assume that baseball teams will still be able to extract value-as they already are. The games aren’t going to be available for free and people will still be willing to pay.