An Angell at Spring Training

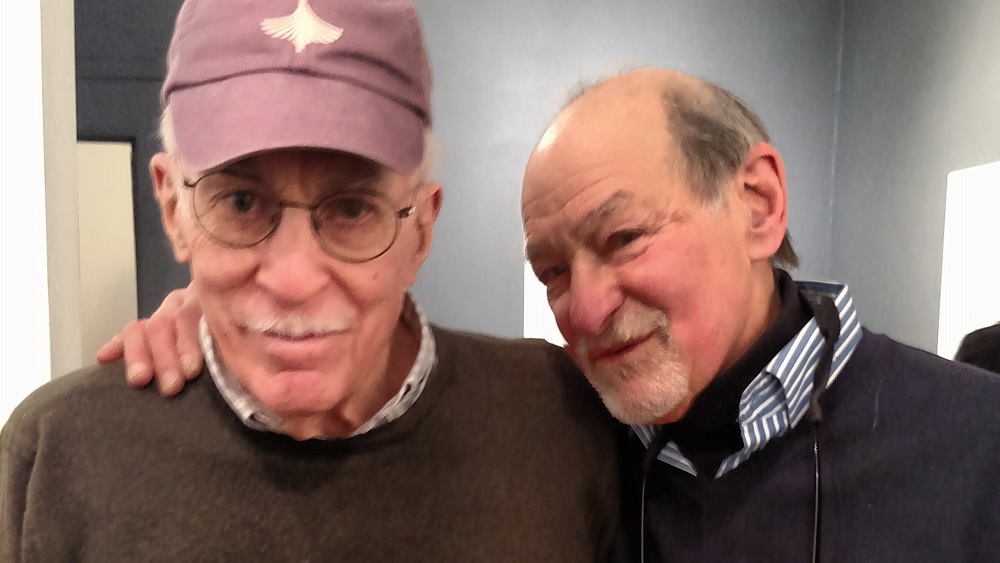

Roger Angell, left, and his words always let us know when spring training has arrived. (via Karen Green)

What I know about spring training I know because of Roger Angell. With conversational elegance and a tireless spirit, he has described this annual baseball ritual as a romantic interlude, more experience than sport, that surely can’t be as romantic as Angell makes it seem.

Angell, a renowned editor and essayist at The New Yorker, has resided, figuratively, since 2014 in Cooperstown, N.Y., at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. No writer may be more deserving.

I’m now working on my sixth decade, and one of my most passionate baseball memories is the dog-eared paperback of an Angell essay collection that sat on my bedside nightstand for much of my youth. Late Innings: A Baseball Companion, published in 1982, is biblical in its importance to my lifelong embrace of the game, an irreplaceable tract of colloquial wit and human observations. People live at the center of every Angell paragraph, people with foibles and talents and stories worth telling. He writes with his eyes more than his hands, a testament to watching and listening and eternal curiosity.

It is now February, with fits of warmth sneaking through, and time to reemphasize this eternal marriage between baseball’s springtime rebirth and Angell’s words.

“These and other dull entanglements of blame and money were swiftly forgotten by me in the clubhouses and grandstands and dugouts of Arizona and Florida this year, where I was repeatedly struck by the humor and eloquence of the players and coaches (and fans and writers) whom I talked with, and by the immense variety of their attachments to this complex game. Once again, it came to me that the gentle, and nearly meaningless, competition in the Cactus and Grapefruit Leagues provides a wonderful quiet space in which we can listen to the true voices of baseball, which are silent in winter and are not always heard in the heat and roar of the summer races.”

Angell, now 99, wrote that passage in March 1978 for a New Yorker essay entitled “Voices of Spring.” I can almost recite it from memory, as if it were the Pledge of Allegiance or the Boy Scout Honor Code. Its final sentence is one of the countless he’s written that cause dreams of springs spent not so much in the early year sunshine but enjoying “the true voices of baseball” — voices I’m not sure exist elsewhere and that seem distressingly absent in the modern game.

It’s debatable that such a “wonderful quiet space” still lives in today’s spring training. The tickets are too expensive, the stadiums too fancy, the experience too corporate. After leaving Disney’s Wide World of Sports near Orlando, the Atlanta Braves this spring are training in a new $139 million complex in North Port, Florida.; plans are under way for $108 million of improvements to the Jupiter, Florida, home of the St. Louis Cardinals and Miami Marlins; renovations to the Florida complexes of the New York Mets (at $57 million) and Toronto Blue Jays (at $102 million) are being unveiled this month.

That’s a stark contrast with Angell’s description of aging parks and geriatric fans and wooden bleachers, which evoke an invitation to something casual, a picnic in the sun. It makes me want to go, and now.

“Big-league ball on the west coast of Florida is a spring sport played by the young for the divertissement of the elderly — a sun-warmed, sleepy exhibition celebrating the juvenescence of the year and the senescence of the fans. Although Florida newspapers print the standings of the clubs in the Grapefruit League every day, none of the teams tries especially hard to win; managers are looking hopefully at their rookies and anxiously at their veteran stars, and by the seventh or eighth inning, no matter what the score, most of the regulars are back in the hotel or driving out to join their families on the beach, their places taken by youngsters up from the minors. The spectators accept this without complaint. Their loyalty to the home club is gentle and unquestioning, and their afternoon pleasure appears scarcely affected by victory or defeat.”

Angell writes about spring training as if it’s unobtainable to the masses, a Utopian experience reserved for Florida and Arizona retirees who have been given a golden gift others cherish from afar. He notices what others miss, or so it seems. In “The Old Folks Behind Home,” a March 1962 New Yorker essay included in 1984’s The Summer Game, Angell described the atmosphere at Payne Park in Sarasota, the longtime — and former — training ground of the Boston Red Sox. When the Red Sox moved to the Cactus League, the Chicago White Sox left Tampa and took up residence in Sarasota.

Angell noticed that framed photographs of Bobby Doerr and Dom DiMaggio still hung on the wall of a Sarasota establishment, the Beach Club Bar. At a White Sox game that day, Angell noted that a young boy still wore his Sox cap — the Boston version. “But these are the only evidences of disaffection and memory, and the old gentlemen filing into the park before the game now wear baseball caps with the White Sox insigne above the bill,” he wrote.

Even today, Angell’s writing from that afternoon is instructive through its description of Payne Park, a now-demolished 4,000-seater that today would barely pass for a middling high school field. Payne Park exemplifies what spring training was then, before March games turned glitzy and Grapefruit and Cactus League parks became million-dollar complexes. “This afternoon,” Angell wrote, “Payne Park’s little sixteen-row grandstand behind home plate had filled up well before game time (the Dodgers, always a good draw, were here today), and fans on their way in paused to visit with those already in their seats … Just after the national anthem, the loudspeaker announced that a lost wallet had been turned in, and invited the owner to come and claim it — an announcement that I very much doubt has ever been heard in a big-city ballpark.”

Much of spring training’s allure isn’t the baseball as much as it is the jettisoning of winter’s awfulness. Indeed, spring baseball can be a slog of lineup changes and pitching wildness and wind-blown doubles. Even so, the anticipation of trading cold for warmth is an emotional experience, especially for those in climates best reserved for outdoor curling.

That was Angell’s sentiment in April 1975, when he documented his travel south a few weeks prior in another New Yorker essay. He wrote, “It was raining in New York — a miserable afternoon in mid-March. Perfect. Grabbed my coat and got my hat, left my worries on the doorstep. Flew to Miami, drove to Fort Lauderdale, saw the banks of lights gleaming in the gloaming, found the ballpark, parked, climbed to the press box, said hello, picked up stats and a scorecard, took the last empty seat, filled out my card (Mets vs. Yankees), rose for the anthem, regarded the emerald field below (the spotless base paths, the encircling palms, the waiting multitudes, the heroes capless and at attention), and took a peek at my watch: four hours and forty minutes to springtime, door to door.”

That was from Five Seasons: A Baseball Companion, published two years after that essay first appeared. Such economical travel isn’t possible today, not with airport security and traffic headaches and the larger crowds spring games now attract. But how mesmerizing it is to imagine being in a Florida or Arizona park, four hours from right now, sitting beside Roger Angell and sharing a meaningless game that warms the soul.

The Five Seasons line I’ve always loved, also written with the eyes more than the hands: “When an Al Lang usher escorts an elderly female fan to her seat, it is impossible to tell who is holding up whom.”

Everything good I learned about baseball I learned from Roger Angell, Thomas Boswell, Bill James, and Bart Giamatti.

I’m old enough to remember baseball back before the all-pervasive greed and the ludicrous salaries destroyed it. Money ruins everything it touches.

I don’t get the point about the “ludicrous salaries.” The players are getting what the market bears. For years, the owners paid them whatever they wanted. I think greed always existed but fans didn’t see it as much because it was the owners keeping all the money to themselves. No offense, but this is just fairy tale nostalgia. You liked it when players took their money and kept their mouths shut.

Money hasn’t ruined baseball. It’s just made things more fair for players.