“Bigger Than the Game” Lives Up to its Title

Bigger Than the Game reminds us that physical health is only part of the equation (via Dirk Hayhurst).

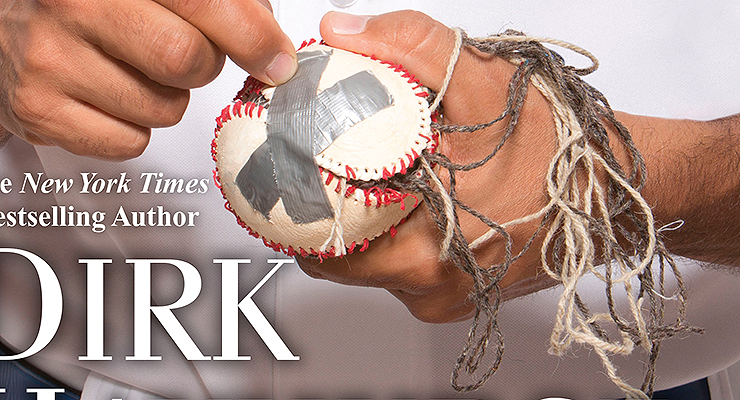

Two steps forward, two steps back. It’s a common refrain, and one that kicks off the latest book by former major league pitcher Dirk Hayhurst, Bigger Than the Game: Restitching a Major League Life. It’s a story that shows how complex life as a baseball player can be, particularly for an injured player.

We are comfortable with how the day-to-day lives work for healthy baseball players, but it’s rare that we learn anything about the injured ones. Mostly you hear “rehab is a tedious grind, but it’s worth it to get back on the field.” Hayhurst’s book delves deeper into what happens when a player is broken physically, but it goes a step further, detailing what can happen when a player is also broken mentally. This is a rare treat, and would be essential reading for this fact alone, even if the tale was not well conveyed. However, the book is an incredibly entertaining rollercoaster ride. At various points during the book–which centers around the 2010 season–Hayhurst is ignored, bullied, threatened, disrespected, pitied, counseled, respected and loved.

Oh, and he gets back-handed by Dr. James Andrews. Twice.

The book starts with the point where he has taken those two steps back. After breaking through with the Blue Jays during the 2009 season, when he posted a 2.78 ERA in 15 contests for Toronto, Hayhurst was determined to get even better. That led him to disobey his trainer’s orders and go back to the gym one night early in the offseason for some late-night upper-body work. Then he hears the horrifying pop in his right shoulder. Many of us can relate to this–I know that I can. Every now and then, we all get a little carried away. For Hayhurst, this had serious consequences, and once he turns up broken, things get dark. Neither remedy nor rest cures his aching shoulder, and eventually surgery is decided needed.

Things move from “this is all I know” fears before his surgery, to feeling isolated during spring training, to washing down a handful of sleeping pills and Oxycodone with a bottle or six of Yuengling so he can fall asleep before the warm Florida sun even sets. It has a very, “boy, that escalated quickly” kind of feel that is more than a little bit startling.

One of the chief members of the team freezing him out and antagonizing him was pitcher Brice Jared. (It’s a made-up name, in case you’re already furiously rushing for the player search. There are enough details about him given that you could probably figure out who it is, but I thought that was kind of taking the fun out of the mystery. There’s also the chance, of course, that the player–or some of the details about him–is an amalgamation of a few players.) Jared and his friends made life difficult for Hayhurst, and their behavior had a lasting mark, probably more than any of them realized.

In reading the book, I kept thinking, “I wonder how many other players have gone through situations like this?” Not necessarily the bullying in specific, although that is a prevalent theme these days. The triggers or reasons won’t be the same in every case, but we don’t spend a lot of time on how players feel. Part of that is that they aren’t very forthcoming, and for good reason. But we also tend to not even wonder about such things. We tend to think of them as robots. Heck, one of my favorite running bits used to be how Joe Sheehan referred to Mariano Rivera as “Cyborg Reliever.” We do hear about some of these struggles after the fact, but generally speaking it’s only when a player is performing abnormally poorly or is arrested or suspended. One recent example of the former was when Torii Hunter spoke out about Prince Fielder’s divorce. There are plenty of examples of the latter, be it stars like Miguel Cabrera and Alex Rodriguez or highly-touted prospects like Matt Bush or Jon Singleton.

When these kinds of things come to the surface, we take a minute to stop and reflect on the situation and put things into better context. I can’t imagine getting divorced or having my children taken away, but in such a scenario I doubt I’d be any good at my job. Especially if my job required the razor-sharp focus it takes to perform as a major league player. But most of the time, these things don’t come to light. Not everyone has chatty Cathy teammates, and plenty of players become self destructive without getting arrested. Hayhurst certainly was. There may be scores of players who washed out of the game after a year or two because life didn’t go according to plan. On occasion there will be whispers about top prospects, usually couched in bland industry terms like “bad makeup” that don’t really mean much. The bottom line though, is that we just don’t know, and there’s probably a good number of players who ultimately wash out of the game because they don’t seek counsel.

Hayhurst reaches rock bottom part-way through spring training, after he is verbally berated by a snot-nosed intern who is offended that Hayhurst asks him for his per diem while he is eating lunch. On the verge of tears, Hayhurst does seek out the Blue Jays team psychologist. But when debating whether to call him, he thinks about how even making the phone call could affect him:

Most of the players avoided him, especially in public. They called him a brain fuck, a blanket for the mentally weak, or a wet nurse for guys who couldn’t handle the stress of baseball life. They’d beat their chests and say, “If you can’t handle the grind of the game, you don’t belong in it.”

There were also some players, mostly the paranoid and superstitious, who thought Ray was there to sniff out those not mentally strong enough to make it to the big leagues. It was believed that once he found out who wasn’t tough enough — and he could do it using his special shrink magic through simple conversation — he’d take that information and report back to the brass. A week later, out of the blue, you’d get released. Players kept exchanges with Ray brief; that way, the doc wasn’t afforded a chance to pick them apart.

This sort of attitude toward mental health professionals is nothing new, especially in the sports world. That Hayhurst delves into the topic in this book, and does so in an honest fashion, however, is new. It’s a great start on a topic that still needs a lot of exploration.

Hayhurst eventually makes the call, and once he gets better–which is an interesting process as well–he gets back to the business of being a rehabbing pitcher, and it’s here where we get some unique insight into the hallowed sanctuary of the injured athlete formally known as the Andrews Sports Medicine & Orthopaedic Center (as well as the neighboring American Sports Medicine Institute).

…

There are a couple of major obstacles when someone is writing a tell-all book or (auto)biography, particularly in the sports genre. The first is that if you’re even vaguely familiar with the subject, you don’t learn anything new.

The other major pitfall is that it takes an extraordinary person or a really excellent writer to be interesting enough to fill a book with stories of nothing but himself. As a result, many of these books are repetitive; you tend to read the same thing over and over, until it feels like a chore to finish. In the sports world, John Schuerholz’s book sticks out to me as an extreme example of this phenomenon.

Hayhurst deftly avoids both of these pitfalls. He puts his foot on the gas pedal and keeps it there, which is refreshing for a sports book. It made the book not only a quick read, but an engaging one. I felt as if I should have been taking notes for topics that are worthy of further exploration, like the differences between illegal amphetamines and legal sleeping pills, the latter of which “a lot of guys get on” in the majors, according to one of Hayhurst’s teammates.

During times when there is heavy dialogue, it can feel stilted. That seems pretty understandable, as Hayhurst had the difficult task of trying to accurately relay years-old events during which he couldn’t possibly have had a tape recorder on, be they moments in bed with his wife or lying on a training table doing range of motion exercises. This is a minor criticism, and certainly one that shouldn’t keep you from reading it.

There is a lot packed into the book, and I am not touching on some of the juicier or more entertaining stuff, like his experiences with Triple H, unicorn stickers, the “Club Med” card, ancient electric stim machines, Southwest Airlines karaoke, Twitter trolls, “Hot Rob,” and Manny Ramirez. But I don’t want to spoil the book for you. Better to go out and get yourself a copy when it comes out tomorrow. You won’t be sorry you did.

Does he have a good sense of humor at all? Is the book funny in places?

I’m thinking of this because Bouton covered some of this territory in “Ball Four,” which was about a physically damaged pitcher and his attempt to make it back with a new pitch, and all the psychological issues that might entail. And IIRC, Bouton says he had to endure some mockery because he was an intellectual and liked to read books that didn’t have pictures. So maybe this could be a sort of modern version of “Ball Four” and worth looking at if Hayhurst has any kind of sense of humor or irony.

A word about this:

“I can’t imagine getting divorced or having my children taken away, but in such a scenario I doubt I’d be any good at my job. Especially if my job required the razor-sharp focus it takes to perform as a major league player.”

You’d have trouble doing your job in this scenario because you probably are (sorry to disappoint you) an ordinary human being. IMO, it’s precisely because pro athletes at the top of the pyramid have that “razor sharp focus” that they should be able to shut out the fabled “distractions” sports reporters are so fond of inventing. (That and, of course, they’re at the top because of their usually extraordinary physical gifts.) I’d imagine the vast majority of ballplayers who can’t put aside everything else — I mean EVERYthing else — for a few hours and concentrate solely on this pitch, this at-bat, get weeded out in A ball.

Give you an example: One of the dumbest questions I’ve ever read from a sports writer was to Tom Brady. Now Tom Brady’s job is to stand in a human hurricane of 300-pound people, half of whom are trying to decapitate him, and throw 60-yard pinpoint passes to his receivers. He’s exceptionally good at this, good enough to get his team in the playoffs almost every year and win the occasional Super Bowl. He’s unusually handsome and makes a bajillion dollars and he’s married to a world-famous model and they and their kids are followed by photographers almost literally every time they step out the front door.

Regardless of all this, he manages to do his job extremely well.

And some sports writer asked Tom Brady if the Aaron Hernandez situation was a “distraction.”

Think about the idiocy of that.

Maybe Tom Brady is an exception among exceptional people, but I’d bet against it. I don’t think you can possibly make it to the top level of pro sports if you’re psychologically weak. If you do and you are, you’re certainly not going to last long. Most pro athletes seem to me to be highly functioning near-sociopaths who managed to channel their conditions into a socially acceptable lifestyle. Yeah, teamwork and all that, but mostly getting where they are involves stepping around, through and over anything and anyone in your path. When we’re being nice, we use words like “driven” and “determined to win” rather than “ruthless” to describe such people.

Obviously, some doubt must creep in from time to time. But that’s a self-generated thing related to performance issues and not necessarily due to outside influences — to “distractions.”

I definitely found that he had a good sense of humor about things.

Good. I’m in.

I have read Hayhurst’s first two books, and find him to be a very funny writer. He’s especially funny, in the first volume, about how he was a sheltered, deeply religious virgin who didn’t drink, and learned to stop being a stick in the mud and open up around teammates. He definitely has a “Would Grab a Pint With” score of 10.

And good. I’m in.

I think it was Thomas Boswell, in “99 reasons baseball is better than football,” who wrote something along the lines of, more good baseball books get written in an average year than have ever been written about football.