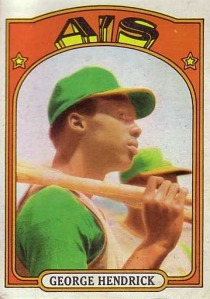

Card Corner: 1972 Topps: George Hendrick

George Hendrick’s 1972 Topps card has long been a source of puzzlement for this confused card collector. I wondered whether his green and gold A’s uniform was airbrushed by one of the artists at Topps. I couldn’t tell for sure. I solicited the thoughts of some baseball card experts. The consensus maintains that there was no airbrushing involved. Instead, they believe that the brightness of the green and gold comes from the glare of the sun in Arizona, where the A’s have traditionally held spring training. With the sun blinding the sky overhead, the card takes on an unusually brilliant, almost surreal tone.

The card is interesting also because it features neither an action shot nor a posed one. The camera has caught Hendrick in a candid moment, with his bat on his shoulder; he looks relaxed and at ease, surprisingly so for an unproven rookie trying to win a job on the Opening Day roster. We see Hendrick from the side, as he is looking toward the right of the camera, looking at someone we cannot see. (We can also see that another player is in the immediate background, but his identity remains unknown, as he is obscured by Hendrick’s hand and bat.)

Rather than a stiff, forced pose, we have an opportunity to see a player in a more sincere moment, the kind of moment that is elusive on baseball cards.

The 1972 season turned out to be a pivotal one in the career of George Hendrick. He had played briefly for the A’s in 1971, but he failed to make the roster out of spring training, instead starting the ’72 season at Triple-A Iowa. Hendrick bided his time in the American Association while fellow prospects Bobby Brooks and Angel Mangual tried to fill the center field gap created by the wintertime trade of Rick Monday to the Cubs. When Brooks and Mangual failed to put a stranglehold on the position, the A’s summoned the lean and lanky Hendrick from the minor leagues. He responded by hitting game-winning home runs in two consecutive games against the White Sox.

Hendrick played well for a brief stretch before showing that he was not ready to handle major league pitching. Hendrick’s wrist-snap batting style reminded scouts of Ernie Banks, who had unusually powerful wrists, but it did not yield the same kind of positive results. So Hendrick became part of Oakland’s revolving door in center field. In addition to Brooks, Mangual and Hendrick, the A’s tried midseason pickups Bill Voss and Downtown Ollie Brown, before finally settling on Reggie Jackson, converted from right field. Hendrick receded into a reserve role, sometimes filling in for Jackson, or starting left fielder Joe Rudi, or whomever the A’s might have in right field on a given day.

Remaining in the shadows for most of the 1972 season, Hendrick found himself in the center of the storm during the postseason. Playing a decisive Game Five of the Championship Series against the Tigers, Jackson injured his hamstring while scoring from third base on the front end of a double steal. Oakland manager Dick Williams called on Hendrick to take Jackson’s place in center field. In the fourth inning, Hendrick reached base on an error by Dick McAuliffe. With Hendrick on second base and two men out, Gene Tenace delivered a sharp single to left field. Hendrick rounded third, swiftly approaching home plate. The fleet-footed Hendrick slid feet first, away from the sweeping glove of catcher Bill Freehan. As Freehan tried to apply a tag, he bobbled the ball, allowing Hendrick to score the go-ahead run.

That run, which would be documented on a 1973 Topps card, would prove decisive. It was the difference in a 2-1 win for the A’s, who advanced to their first World Series since the franchise’s days in Philadelphia.

With Jackson unavailable due to a torn hamstring, Williams decided to move Hendrick into center field for Game One. About an hour before the first pitch, Jackson spent several minutes talking with the rookie outfielder, instructing him on the subtleties of playing center field at Cincinnati’s Riverfront Stadium.

Hendrick played five of the seven Series games against the Reds, but he batted only .133. That winter, the A’s considered the possibility of trading him, in part because of his reputation as a loner who was not very cooperative with the media. According to one wintertime rumor, the A’s considered a trade that would have sent Hendrick to the Rangers for veteran right-hander Dick Bosman, but the deal never took place.

Remaining with the A’s, Hendrick reported to spring training but quickly became unhappy with his situation in Oakland. He met with owner and GM Charlie Finley, who told him that he would not be considered for the starting center field job. The A’s planned to have Hendrick start the season at Triple-A, playing for Oakland’s new affiliate in Tucson. Hendrick, who had experienced the thrill of starting games in the World Series, wanted no part of extended duty in the minor leagues. He asked Finley to be traded.

On March 24, Finley announced a major four-player trade, sending Hendrick and catcher Dave Duncan to the Indians for former All-Star catcher Ray Fosse and utility infielder Jack Heidemann. The trade was especially interesting because of Finley’s decision to make a trade with Cleveland. When Hendrick had asked to be traded, he had expressed an interest in being dealt to the Indians. (I’m not sure why that was the case; Hendrick wasn’t from Cleveland, but from east Los Angeles. Perhaps he just realized that the Indians needed help in the outfield.)

Though Hendrick had been upset by Finley’s initial plan to have him start the season in Triple-A, the young outfielder took something favorable from his time in Oakland. He credited Joe Rudi with helping to make him a more complete player, especially on defense.

The Indians would benefit from Rudi’s tutelage. The Indians could also offer Hendrick a situation that the A’s could not: plenty of playing time. While Oakland’s talented outfield included Jackson and Rudi, and an emerging young center fielder in Billy North, the Indians had more questionable talents in their outfield. On Opening Day, Hendrick started in center field, flanked by journeymen Charlie Spikes in left and Rusty Torres in right. By the end of the 1973 season, Hendrick hit 21 home runs and slugged .452, while establishing himself as the best all-round outfielder on the Indians’ roster.

All should have been well in Cleveland. A few of Hendrick’s supporters lauded his style of play as smooth and effortless, but his detractors considered him lazy. Even opposing coaches criticized Hendrick. “He’s a real dog,” Yankee coach Elston Howard said in a brutally candid interview with sportswriter Dick Young. “You could see that the way he played against us. Half-trying. What a shame.”

Critics aside, Hendrick made the All-Star team in 1974 and ’75. He put up decent OPS numbers, usually in the .760 range, but his defense in center field was found wanting, resulting in a move to right field, and then to left. Though Hendrick didn’t walk much and never hit more than 25 home runs in a season, he emerged as a good, solid everyday player who would hit .280 to .300, steal a base on occasion, cover the ground in an outfield corner, and discourage opposing baserunners with a strong throwing arm.

Yet, a lack of effort continued to cloud Hendrick’s reputation. He would not always run out routine ground balls or pop-ups. In particular, he irritated Indians manager Frank Robinson, an old school baseball man who had played the game with fire and verve. After the 1976 season, the Indians made what would turn out to be a foolish trade, sending Hendrick to the Padres for platoon outfielder Johnny Grubb, backup catcher Fred Kendall and utility infielder Hector Torres. It was exactly the kind of unwise transaction that would epitomize Indian fortunes during the frantic 1970s.

Hendrick responded by putting together his finest season in 1977. So how did the Padres react? They traded him the following year, sending him to the Cardinals in midseason for right-hander Eric Rasmussen. Much like the Indians, the Padres would come to regret the trade.

The move to St. Louis would turn out to be the best break of Hendrick’s career. More a line drive hitter than a pure slugger, Hendrick found St. Louis’ Busch Stadium to his liking, with its big gaps in the alleys and fast artificial turf. Sharing the middle of the order with Keith Hernandez and Ted Simmons, Hendrick boosted his OPS to the .840 range. He hit .300 or better three times for the Cardinals, while reaching the 100-RBI mark twice. In 1982, he became an important part of the Cardinals’ world championship effort, as St. Louis defeated Milwaukee in the World Series. For his efforts, Hendrick earned his second world championship ring.

Hendrick also showed the ability to adjust. After Cardinals manager Whitey Herzog reprimanded him once for not running hard, Hendrick took heed. He started to run out grounders and fly balls. And when the Cardinals made the controversial trade that sent Hernandez to the Mets, Herzog asked Hendrick to move to first base fulltime. Hendrick made the move willingly; in fact, he had been the one to approach Herzog earlier about taking ground balls at first because he was concerned that one day he would no longer be able to play the outfield. Moving to first base without a whimper, Hendrick cemented his standing as a popular player with both his teammates and Cardinals fans.

Although Hendrick played the best ball of his career for the Cardinals, he remained somewhat of an overlooked player. That was partly his own doing, specifically his continuing reluctance to talk to the media. By now, Hendrick was well known as “Silent George,” a player who was unwilling to cooperate with any form of media. (Hendrick reportedly became upset with reports about his off-the-field activities, thus he instituted his ban against the media.) Other detractors called him “Jogging George” or “Captain Easy,” in reference to his past reputation as a player who did not always hustle.

Hendrick also became known for doing things his way. He would let the bottoms of his pant legs all the way down to his ankles, so that they would cover his stockings. He became the first player to do so—everyone else in baseball showed their stockings and stirrups at the time—making him a pioneer in baseball fashion.

After the 1984 season, the Cardinals traded Hendrick, not because of any dissatisfaction with him, but because they needed pitching. Dealt to the Pirates for John Tudor, Hendrick wrapped up a long career with a forgettable tenure in Pittsburgh, followed by a large trade that sent him, John Candelaria and Al Holland to the Angels for three younger players. By now Hendrick was in his late 30s and very much on the decline. After the 1988 season, he became a free agent, but ended up retiring.

To the surprise of many, Hendrick turned to coaching after his playing days. He didn’t seem like the coaching type, given his quiet, laid-back nature, but appearances can be deceiving. He joined the Cardinals, the organization where he had succeeded the most, and later coached for the Angels and Dodgers. He eventually became the first base and outfield coach for the Rays; it’s a position that he has held for the last six seasons.

While he was coaching with the Cardinals one spring training, I had a chance to meet Hendrick. Working as part of a Hall of Fame multimedia crew, I was conducting video interviews for the Hall’s archive. I knew about Hendrick’s reputation for being non-talkative, but I decided to approach him anyway, partly because we had found coaches to be among our best interview subjects. I asked George if he would be willing to answer some questions. He declined politely, explaining that he preferred the spotlight to be on the players, and not the coaches. Even though he had turned me down, he couldn’t have been nicer about it.

My favorable impression of Hendrick was confirmed by one of my cohorts at the Hall of Fame. This person had met Hendrick while he was playing minor league ball for the Burlington Bees in the late 1960s. They talked for two full hours, engaging in a pleasant and wide-ranging conversation. Later on, Hendrick sent my Hall of Fame colleague an autographed baseball.

It turned out that Silent George is a pretty good guy after all.

Excellent article—thanks.

Great article. I always liked George Hendrick. He was well established with the Cardinals by the time I was paying attention.

One thought on the extreme airbrushing, since it seems to be applied to the entire card. Is it possible Topps missed getting his picture, and since he was a rookie, there were none in a A’s uniform? They then took a picture of him in Iowa, or found a file picture at some other time, and airbrushed the entire A’s uni, as well as his neighbor standing next to him. And when they saw how out of place all that airbrushing looked, they decided the best solution was to airbrush some more, doing a once over on his face, hand and bat. Just a wild hypothesis.

Thanks Bruce, Silent George was one of my favorites growing up. I was quite distraught when the Cards traded him, but after Tudor’s ‘85 season, I clearly understood why. Also, that was the same winter that the Cards traded for Jack Clark, moving Dave LaPoint, David Green, a middle infielder (Uribe I think) and another for him. I’ve always been hopeful that Hendrick makes his way back to St.Louis in some sort of coaching capacity.

Thanks, guys.

Jim, though I tend to believe it’s the lighting, I do think there’s a possibility that the photo was airbrushed.

It’s also been suggested to me that Topps took a black-and-white photo (assuming that’s all they had of Hendrick) and then colorized it. I know that Topps did that in later years with Rick Jones (1977) and Mike Paxton (1978). And there probably are other examples from the 1980s.

Poor George. Growing up a Tribe fan in the mid 70s that’s about all we seemed to hear – he was “lazy”, etc. I always liked him, though I was surprised that he had so much success for so long after he left Cleveland.

I wouldn’t call Charlie Spikes at that time a “journeyman”. Granted, the Indians got fleeced (what else was new)in the Graig Nettles trade, but Spikes was supposed to be a super prospect (yeah just like Ted Cox 5 years later) with lots of power, and the rookie outfielders Hendrick and Spikes generated quite a buzz.

I’ve always thought that the whole card was colorized from a black-and-white photo. That’s why the green is so vivid and his face looks so… i don’t know what you’d call it….. washed out?

George Hendrick once spoke to a joint meeting of the LA (Allan Roth) and San Diego (Ted Williams) SABR chapters before a Lake Elsinore baseball game.

Hendrick was quite talkative, but he spoke extremely softly, so people were literally hanging on to the edge of their seats to listen to him.

He definitely thought highly of Herzog. And he didn’t care for Gene Mauch at all. He thought Herzog’s greatest feat was getting John Stuper’s greatest pitching performance of his life in Game 6 of the 1982 World Series. And he believed that every managerial move that Mauch made in Game 5 of the 1986 ALCS was wrong.

He also claimed he didn’t play much organized baseball and was spotted playing in a Sunday game that he just showed up for to help a friend fill out a team. That story I was a bit skeptical of.

The sun? Impossible. That whole card looked like it was airbrushed from a recent Topps artist who may have been 6 at the time. Even Hendrick’s face looks airbrushed. Plus look at that other hat and jersey. Or it was the worst film ever used.

Hendrick the coach is responsible for one of my favourite baseball stadium moments. I was at the Rays-Jays game a couple seasons ago when Brandon Morrow took a no-hitter into the ninth. Randomly, Joe Carter was there for the game, sitting along the first base line just past the dugout, and the PA announcer had officially welcomed him before the game.

At some point during the game, a Rays hitter fouled a grounder down to first, which Hendrick fielded, then turned to toss into the crowd. Seeing Carter, he tossed it right to Joe, who first seemed surprised, then waved his arms like the happiest 8-year old present, before handing the ball off to someone else. I can’t even tell you why it was so funny, but I lost it laughing when it happened.

My favorite memory of Silent George was him sauntering in from right field into the Cardinals bullpen in between innings and resting on the bullpen bench instead of coming into the dugout.

He was a very smart hitter. If there was no compelling reason to get a hit, he wold wve at a couple curveballs and let the pitcher strike him out. Then later in the game with RISP, he’d wait for that curveball and poke it into right field for a couple RBIs

George Hendricks was and is a really classy guy. He signed autographs with no fanfare and just simply a quiet dignity when he was a youngster for the A’s. Very polite, very unassuming. I remember that even when Charley Finley was ranting about “all the greedy and ungrateful ballplayers”, he seemed to have a nice word about George.

George Hendrick is one of my all-time favorite players. I started following him when he was traded to the Indians along with Dave Duncan, another of my all-time favorites (and who received about a dozen write-in votes for the All-Star game in 1975 while playing for the Orioles). Anyway, I got to see Hendrick and Spikes play in person at Memorial Stadium on May 23, 1974, a game in which Gaylord Perry shutout my O’s 2-0 on his way to a Cy Young campaign. I’ve read several articles about Hendrick in the Sports Illustrated Vault and each casts him in a very positive, fan-friendly light. Great articl Bruce!!

The most surprising thing that’s come out of writing this article is the number of people I’ve heard from who met George Hendrick and have nothing but good things to say about him. Hendrick had such a negative reputation during his career, but people seem to genuinely like the guy. It’s nice to hear.

George Hendrick is a jack___. 99.9% of the adult fans he interacts with can’t stand him. Especially adult fans that bother him with autograph requests. They’re trash in his eyes. In particular the ones that put a baseball card in front of him he doesn’t like. He’ll only sign particular cards.

I will give him prop’s for being nice to kids. Put a youngster in front of him and he’s a completely different person. Especially if that teenager is a girl. I didn’t think the guy had teeth until I watched him fall over himself a few times around the young ladies.

One interesting thing about his career was he refused to bat against knuckleballers. Claimed it messed up his swing for weeks. As a kid I found it odd that a professional athlete would run from a challenge. Now that I’ve seen him up close I’m not suprised.