Card Corner: 1975 Topps Set Reflected the Era

(via Michelle Jay)

There may be no more innovative decade for baseball cards than the 1970s. It was a decade that began with Topps’ introduction of gray-bordered cards in 1970, and then the daring black-bordered cards of 1971. It continued with the highlighting of action cards in 1972, and then a proliferation of long-distance action in 1973. After a bit of a dull offering in 1974, Topps made further impact on the hobby in 1975 by issuing its first set of cards featuring multi-colored borders.

With all sorts of combinations of green, purple, blue, yellow, and red, the 1975 set became reflective of an American culture that had become almost obsessed with bright and vibrant colors. In a decade when color television, bright polyester tones (often hideous on the clothing that we wore), and gaudy home designs all exploded within popular culture, baseball cards did their best to keep pace.

The result was a set of cards that has become a favorite of collectors of vintage cards. The colored borders have created problems—principally the borders chips so that even the slightest imperfections can be seen—but those same borders have produced a unique look that make the 1975 set arguably the most desired cards of the entire decade.

The multi-colored borders certainly headline the 1975 cards, but they are not the only distinguishing feature or highlight. If you’re in search of top-tier rookie cards, you’ll find two highly desirable ones for George Brett and Robin Yount, each of whom saw his first extended major league action in 1974. At the other end of the spectrum, you’ll find the final regular issue card for the great Bob Gibson, who still looks surprisingly youthful for a ballplayer in his late 30s. Then there’s the curiosity of the first card that shows Hank Aaron as a member of the Milwaukee Brewers, even if the Brew Crew’s colors have been airbrushed onto an older photo of “Bad Henry” wearing the uniform of the Atlanta Braves. There is also a classic case of mistaken identity within the set: Steve Busby’s card actually features a photograph of catcher Fran Healy, at a time when Busby was well known because he had thrown two early-career no-hitters.

From an aesthetic standpoint, the 1975 set boasts its share of solid photography, both in terms of posed and action shots. The set also gives us a clear peek at the changing culture of player fashion and appearance. By 1975, the days of military crewcuts and clean-shaven faces was over. In their place, we can find a sea of players sporting long hair (Dave Duncan and Ted Simmons), oversized Afros (Jose Cardenal and Oscar Gamble), mutton chop sideburns (Buddy Bradford and Larry Milbourne), full beards (Reggie Jackson), Fu Manchus (Garry Maddox), and mustaches (Cleon Jones) that would have made Burt Reynolds proud. If you’re looking for a snapshot of what baseball looked like in the middle of the 1970s, look no further than 1975 Topps.

In a year chock full of quality cards, a select few offerings that have emerged as personal favorites. Let’s take a closer look at six cards from the world of 1975 Topps.

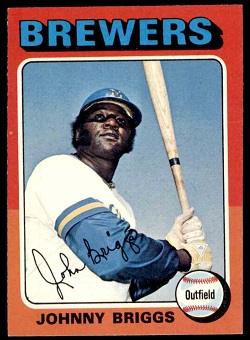

Johnny Briggs: At first glance, this might appear to be one of those typically dull shots of a batter posed with a bat in hand, but there’s actually a lot more here. Taken from a slightly lower angle than usual, the photo gives us a hint of Briggs’ size, particularly his muscular right arm, which looks large and powerful enough to grind his bat into sawdust.

The card also gives us a nice peek at ballplayer fashions of the 1970s. Briggs is sporting some of the best mutton chop sideburns of the decade, perhaps second only to Mudcat Grant (as seen on his 1972 card). Briggs’ Afro, while mostly hidden by his helmet, looks a bit frizzy and overgrown on the sides, reflective of the tendency of players to wear their hair much longer after the conservatism of the 1960s. We can also see something light-colored under Briggs’ helmet. It might be a cap, which many players wore under their helmets during the ’70s, or it might be a headband, used by only a few players (such as Tito Fuentes) at the time.

Briggs is also wearing a windbreaker under his jersey, something that was done often by players of the era, especially during spring training. And then there are the white batting gloves that stand in contrast to the blue windbreaker. It was only about a decade earlier that Ken Harrelson had dared to alter the game’s fashion landscape by wearing a batting glove; at first, the Hawk was ridiculed by his fellow players, but by the mid-1970s, batting gloves had become omnipresent. It seems the Hawk knew what he was doing.

Beyond his physical appearance, Briggs was a fascinating player . In the 1960s, he had come up with the Philadelphia Phillies as a lithe and speedy center fielder who batted leadoff while playing for Gene Mauch. By the time he joined the Brewers in 1972, he had made the transition to burly slugger and corner outfielder, while adding considerable weight to his previously athletic frame. In ’72 and ’73, he hit a combined 39 home runs, and played so well during the latter season that he received some back-of-the-ballot support in the American League MVP voting.

Briggs also became involved in a noted controversy with the Phillies, one in which he actually did nothing but serve as a verbal target. On July 5, 1965, the Phillies prepared to play a game against the Cincinnati Reds. As the players milled around the clubhouse, outfielder Frank Thomas allegedly referred to Briggs as “boy” several times, prompting an angry response from fellow Phillie Richie Allen. (Thomas has disputed this, but some Phillies say that it did happen.) When Allen stood up for Briggs, Thomas responded by swinging a bat at Allen. Not one to back down, Allen cocked his right arm and took a swing at Thomas, nailing him with a solid punch to the jaw, which resulted in a facial fracture. Five days later, the Phillies sold Thomas to the Houston Astros.

With Milwaukee, Briggs became a fan favorite; he liked the city so much that he and his family remained there after his career ended. Eventually moving back to his hometown of Paterson, New Jersey, Briggs found a new calling as a corrections officer in the sheriff’s department. He also worked as a recreation supervisor, a job that included coaching baseball and offering advice to youth. Combined with his athletic accomplishments, that kind of work has helped make Johnny Briggs a legend in the Paterson community.

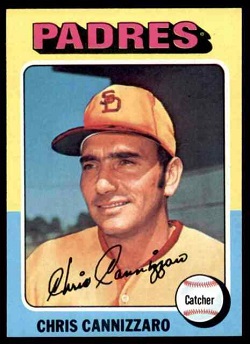

Chris Cannizzaro: Of all the 1975 card offerings, this one may be the gaudiest. It marked the final appearance on a card for Cannizzaro, a journeyman catcher who endured numerous stops and starts during the 1960s and ’70s. This card, which shows him as a member of the San Diego Padres, is just garish, with the bright yellow and powder blue borders playing off against the radioactive airbrushing of Cannizzaro’s uniform jersey and cap. The Topps airbrush artist appears to have mixed bright yellow with splotches of light brown. He also may have added some Crayola to the cap in creating an awkward “SD” logo that could best be described as makeshift. There’s an almost childlike quality to the artwork, reminiscent of some of my own drawings from first grade at Iona Grammar School. It’s certainly not fine art, but it’s still weirdly good, in a strange kind of way that was typical of the 1970s.

What’s also interesting about Cannizzaro’ card is the need to resort to airbrushing in the first place. Cannizzaro played 26 games for the Padres in 1974, and had previously played for the original Padres teams of 1969 and ’70. So there were several opportunities for Topps to acquire photographs of him wearing actual San Diego colors, even if they represented a different Padres uniform design.

As it turned out, Cannizzaro would never appear in a game for the Padres in 1975. He reported to spring training, but failed to make the team’s Opening Day roster. The Padres instead went with younger catcher Fred Kendall, backed up by veteran Randy Hundley and assigned Cannizzaro to their Triple-A affiliate, the Hawaii Islanders. For veteran minor league players in the 1970s, there was no better locale than Honolulu. Cannizzaro served as a player/coach for the Islanders.

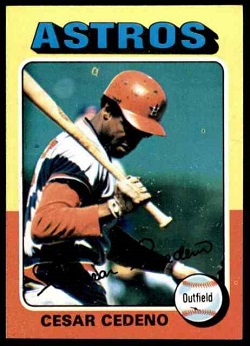

Cesar Cedeno: In contrast to the Cannizzaro card, Cesar Cedeno’s provides us with one of the highlights of 1975 Topps. The colored borders, a lively combination of red and yellow that nicely complement the Astros’ uniform colors from 1974, help give us an aesthetically attractive card. The Topps cameraman also graces us with a clear action photograph. And it’s not a typical action shot, either. Most of the time, Topps photographers were stationed in-camera wells beyond the first and third base dugouts, explaining why we so often see side shots of hitters at bat. Instead, the photographer has taken the photo from an angle not often seen on cards: from directly behind home plate. As he digs his toehold into the batter’s box, we see Cedeno as if we were the umpire, and not just a fan.

The photo was taken during a sunny afternoon game during the 1974 season. The locale is Wrigley Field, as evidenced by the ivy, which is quite blurred but still distinguishable, in the background of the photo. Given the relative clarity of the photo, the sun-splashed afternoon at beloved ballpark like Wrigley, and the not-so-ordinary angle from which the photographer has done his work, this card has become a personal favorite of mine.

Such an attractive card seems appropriate for Cedeno, an all-world talent who was coming off a remarkable three-year stretch with the Astros. In each of those seasons (1972 through 1974), Cedeno made the All-Star team, won a Gold Glove, and received votes in the MVP balloting. His OPS marks of .921, .913, and .799 become even more impressive in light of his home ballpark, the Houston Astrodome, an offensive boneyard that suppressed power numbers as much as any park of the era. Ironically, Cedeno’s career would start to fall off in 1975—some would say the aftereffect of a tragic episode from 1973—though he remained a very good player through the end of the 1977 season.

Cedeno’s best seasons came in 1972 and ’73, right before he became embroiled in tragedy and controversy; an incident with a gun resulted in the death of his girlfriend. (At first Cedeno was charged with voluntary manslaughter, but an investigation determined that the woman had actually fired the gun, resulting in a reduced charge of involuntary manslaughter against Cedeno.)

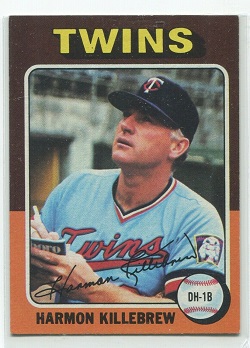

Harmon Killebrew: People often ask me, “Who are the nicest guys you’ve ever met among the Hall of Famers?” For me, any list would have to include Brooks Robinson, Fergie Jenkins, Dennis Eckersley, Orlando Cepeda, and Don Sutton, and at least two deceased members of the Hall, Killebrew and Robin Roberts. They all are—or were—very approachable, very gracious, and terrific ambassadors for the game. It would be harder to find anyone kinder than Killebrew. He was the kind of guy who took an interest in you, as if you were the Hall of Famer and he was just the guy working at the Hall. Humble, caring and gentlemanly are words that come to mind.

So it’s no surprise to find Killebrew signing autographs at a road ballpark on his 1975 card. Not only that, but it’s completely within character to see Killebrew making eye contact by looking directly at the fan asking for his autograph. I could imagine him politely saying to the fan, “How would you like me to sign this?”

Killebrew always treated fans well. He also took special care in signing the actual autograph. He was known to take his time, and write his name neatly and cleanly, so that anyone could tell that it was his name on the autograph. Harmon didn’t much care for how so many modern day athletes had developed the habit of scribbling their names; for him, signing the autograph was an art form, a source of pride.

Killebrew’s 1975 card also brings some bittersweet memories. He played almost all of his career with the Minnesota Twins’ franchise (including some time in Washington), but did not play for the team in 1975, the year that this card, his final one, came out. The Twins released him that January, just before spring training, allowing him to find employment with another team. He signed with the Kansas City Royals, who believed that Killebrew could fill a void at DH.

Of all the teams that could have signed Killebrew, the Royals seemed like one of the oddest fits. They played in Royals Stadium, with its artificial turf and long outfield dimensions. Those were not the kind of features that suited his game, which was based on power and not speed. By 1975, Killebrew was already 39 years old, and suffered through a tough season in which he batted .199 with an OPS of .692. It was a far cry from all those years when Killebrew led the league in home runs (six times) and in walks (four times).

The 1975 card is a reminder of the end of his career. But it’s also a reminder of how ballplayers can be at their best: kind, considerate, and willing to give some time to their fans. Whenever I recall Killebrew, I think of him as a great player, but a better man.

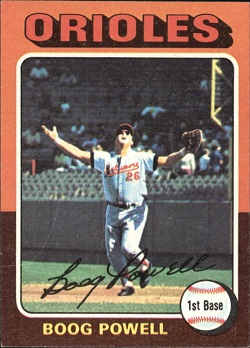

Boog Powell: This is one of the best action shots of the 1970s, if only because it’s so open to interpretation. It’s difficult to know for sure why Powell is approaching an infield pop-up with his arms spread wide apart. Either he’s screaming, “I’ve got it!” or he’s yelling, “Where is it?” Given that Powell is wearing sunglasses, I’m inclined to guess the latter, that Powell has lost the ball in the sun. But that’s only a guess. We’ll never really know for sure.

Whatever our interpretation might be, Powell’s card shows him in a defensive posture, and that’s not the way that most of us remember him. We tend to think of Powell with a bat in his hands, but that’s not really fair. Much like another first baseman of the era (George Scott), Powell’s beefy physique belied his efficiency with the glove. Powell was surprisingly graceful and sure-handed. For much of his career, Powell was a solid defensive first baseman on an exquisite Baltimore Orioles infield that sported Dave Johnson and then Bobby Grich at second base, Mark Belanger at shortstop, and Brooks Robinson at third.

This is the last card that showed Powell playing for the Orioles, even if the photograph is severely out of date. The photo appears to be at least three years old, given that Powell’s road uniform is made of flannel and features “Baltimore” in script. The Orioles last wore these flannel road uniforms in 1972 before switching to polyester in 1973. That’s also when they made the switch to having “Orioles” spelled out in script on the front of the jersey.

After the 1974 season, Baltimore traded Powell to the Cleveland Indians, where he played all of 1975 and ’76 before finishing his career with a Los Angeles Dodgers cameo in ‘77. Powell would appear on one more Topps card (in ’76), one showing him wearing the gaudy red uniform of the Indians, but it’s the 1975 card that stands out as the most intriguing of his long career.

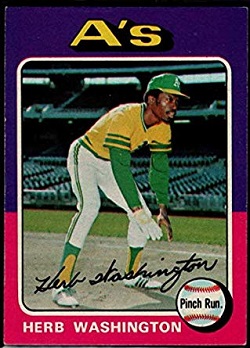

Herb Washington: Of all the 1975 cards, Washington’s is unique. In the lower right-hand corner, we can see Washington’s unusual position printed in black type within the silhouette of a baseball. It is the only card in Topps history to show a player’s position as “Pinch Run,” which is short for “Pinch Runner.”

Actually, there was no other way to describe Washington’s role with the A’s in the mid-1970s. Washington did not play a traditional position in the field, never took an at-bat in a major league game, and never threw a pitch for the Oakland A’s. Washington was not a baseball player per se; he was actually a football player and track star who had excelled in the latter sport at Michigan State. After playing some ball in high school, Washington never played baseball at the collegiate or minor league levels before being signed by Oakland owner Charlie Finley in 1974.

As part of Finley’s obsession with specialization, Washington became a designated pinch runner, usually inserted in the late innings of close games, with the express purpose of attempting to steal a base. That’s the very focused role that Washington filled, with mixed success, over the span of two seasons. At the low point of his career, Washington was picked off in Game Two of the 1974 World Series, a victim of Mike Marshall’s lightning-fast spin move. That made Washington somewhat of a goat in the defeat, but it did not prevent the A’s from winning the World Series in five games.

Washington often struggled in his ability to read opposing pitchers, but once he started running, his sprinter’s speed put him in an elite category that might have challenged the likes of Willie Wilson. Washington’s specialized skill did not go unnoticed by Topps photographer Doug McWilliams, who felt that the player’s unusual situation warranted a special pose for his 1975 card. Prior to a game at an empty Oakland Coliseum in 1974, McWilliams asked Washington to stand on the infield dirt, instructing him to take a lead off of first base, against a pitcher and catcher who were not even there. Washington obliged the request, giving us a piece of baseball card history. Released after the 1975 season, Washington would never again appear on a Topps card.

Beyond the unusual pose and the unique position listing, the Washington card reflects the time period of the mid-1970s. Washington is wearing the bright gold jersey and green undershirt sported by the A’s, which makes for an interesting color contrast against the rather outlandish colored borders of purple and pink. (Purple and pink? My goodness, Topps had fun with this set!) This card gives us a kaleidoscope of colors, in a way that only the 1970s could have done.

Even as seen through this small sampling of cards, Topps’ 1975 set gave us a full range of attributes, from innovation and color to unusual fashion sense and a more personal look at the players. While it’s true that the set is too gaudy for the taste of some collectors, that shouldn’t detract too much from the impact that it has had on two groups of fans: those who remember the 1970s, and those who came after it. Even if 1975 Topps doesn’t suit your preference to a T, it’s a set that tells us a lot about what the game was like 45 years ago.

Definitely a great set. Interesting choices of cards to illustrate it. As always, fascinating ride Bruce

Thanks for the trip down memory lane. How could you not mention the “mini set” version of these cards? As a kid, those mini cards were a neat distraction.

This set & the 78 one are my personal favorites.

“(often hideous on the clothing that we wore)” Wrong! The operative word is “always.”

I’ve always found the 75 set to be uniquely unattractive, though I’m sure others would disagree. And if you’re looking for gaudiness the 1972 set, which is probably the most dissimilar to any other Topps set ever, sets a pretty high bar.

The set of that era that I’ve always liked best aesthetically is the 1976. A vivid color approach just like the 75, but more artistic/restrained in its use, and a really attractive layout. The pictures are of higher quality too, and the cards are of a better stock and have more gloss.

I will happily pre-order any book you might wish to write about baseball cards. Your comments are insightful and interesting, and your passion for these cards is evident. Seriously, how could you not want to write a book about baseball cards, and how could it not be a success?

Great article, as always, Bruce.

While Herb Washington was not a great runner (successful stealing only 64% of the time in 1974) I always liked the concept of a good pinch runner on the bench. The Yankees team of the late 1990’s used to have one (ie Homer Bush) on the postseson roster.

Perhaps, especially with the new 3 batter rule for relief pitchers, a designated pinch runner will be the new 26th roster spot on the end of the bench? Billy Hamiton or players of his ilk could be a real difference maker.

Correction: Boog had a regular issue card in 1977 as well. A nice looking and colorful posed shot of him in his Indians uniform. Again, another fun read Bruce.

My first year collecting cards was 1974 when I was 7. The next year my friend across the street and I went in together on collecting so we could try to collect the whole set. When I moved away in 1977, all those cards got left behind with my friend. It’s the only set from 1974 through about 1986 when I stopped collecting for which I have almost no cards.

True fact: as an 8 yo kid in Minneapolis in 1975, I can probably name more 1975 Minnesota Twins than I can from any current MLB team 🙂