Card Corner Plus: The Frank Robinson Story

(via Michelle Jay)

Here’s one way to tell a difference between a casual fan and a diehard fan.

The casual fan thinks of Frank Robinson as a fine player and the game’s first black manager.

The diehard fan thinks of Robinson as one of the greatest outfielders of all time and a fiery manager who never met an umpire who could force him to back down.

There’s little doubt that Robinson was a terrific all-around player, a five-tool talent, an aggressive and smart baserunner, and a hard-nosed competitor; he is easily one of the 10 greatest outfielders in the history of the game. All of these evaluations came to mind on February 7, when we learned that the player known as “The Judge” had lost his long battle with cancer. More than two months later, it’s still difficult to accept that such a tough, unbreakable player is gone.

In addition to his ample talents on the field, Robinson encompassed longevity, as his career bridged the gap from baseball in the 1950s to the far different game of the 1970s. When Robinson started his career, the Negro Leagues were still active (though not as strong as they had been during their pre-1947 peak). By the time Robinson had finished playing, expansion baseball had taken hold, the designated hitter had been born, and a number of racial barriers had been crossed.

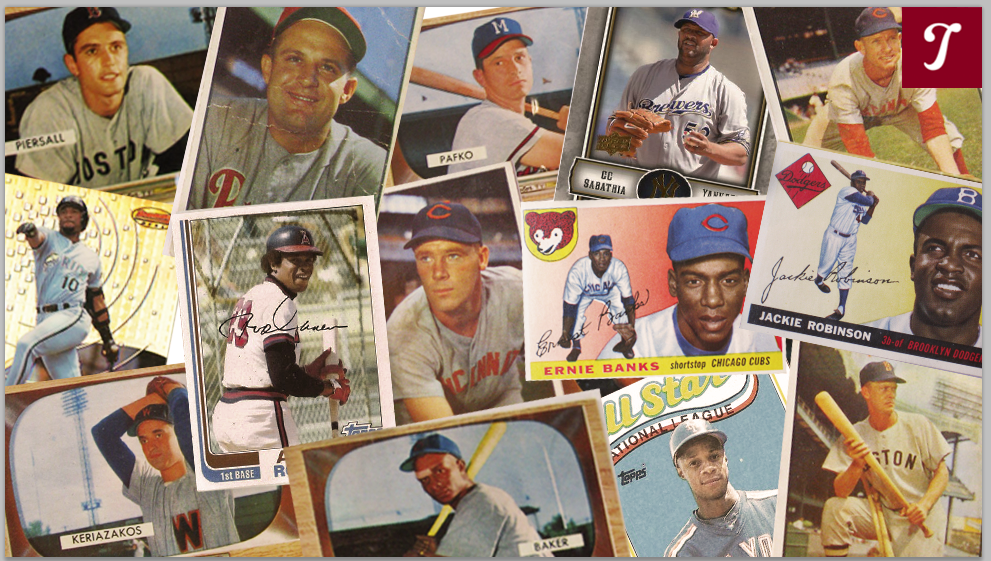

One way to gain additional insight into Robinson’s long career is to examine a cross-section of his baseball cards. The early cards showed him long and lean; his final Topps card presents him in airbrushed glory, sporting the colors of the team that had seen fit to make him the deserving choice as the major league’s first African-American manager. Let’s take a closer look.

Robinson’s depiction on cards began in 1957 (one year after he debuted for Cincinnati and won the Rookie of the Year Award), when Topps issued one of its most simply designed card sets in history. Known for its pedestrian graphics and unencumbered photographs, ’57 Topps allows us to see Robinson in the youthful stage of his career, his thin frame draped in a loosely-fitting sleeveless Reds uniform.

Aside from his rangy stature, what stands out most about the card is the way that Robinson grips the bat; he is choking up a solid two to three inches from the knob. That’s not how I remember Robinson—in his later years with Baltimore, I recall him gripping the bat just a hair above the knob—but it’s the style that he used during his early career in Cincinnati. I guess we shouldn’t be surprised to see Robinson choking up on the bat. Only once in his career, did he strike out as many as 100 times in a season. In fact, he walked almost as frequently as he struck out, always a sign of a smart and dangerous hitter.

In 1959, Topps gave us a very different look at Robinson, this time without a bat, but with a glove in hand. It’s a posed shot from Crosley Field, with a decent-sized crowd in the background, indicating that the photo was taken only a short time before the start of the game. Robinson gives us somewhat of an awkward pose (perhaps at the request of the photographer), his hands outstretched below his knees and his bare hand planted into his mitt, as if he has just fielded a ball about a foot above the ground. It’s a weird pose, somewhere between catching a ball in the air and fielding it on a bounce. Robinson is also smiling subtly, as if to tell the Topps photographer that this is not exactly typical of how he fielded balls hit his way.

Defensive prowess is not what we remember most about Robinson, but it’s worth noting that he won his only Gold Glove in 1958, the same year that this photograph was taken. He remained an exceptional right fielder for much of his career, with good range and a strong throwing arm, at least until he hurt his shoulder with the Orioles. If not for the simultaneous presence of Roberto Clemente in the National League and Al Kaline in the American League, I suspect that Robinson would have won several more Gold Gloves with both the Reds and the Orioles.

As we move into the 1960s, we see Robinson becoming part of a new Topps tradition: the combination card. (Robinson would appear on three such cards during the 1960s.) The 1961 card headlined “Reds’ Heavy Artillery” is one of my favorites; we see Robinson, Vada Pinson, and Gus Bell, all outfitted in those memorable Cincinnati uniforms of the era, carefully examining their bats.

The trio had formed the Reds’ starting outfield for a portion of the 1960 season, at least on those days when Robinson didn’t play first base. Anticipating that the three would form the nucleus of the Reds’ offense in 1961, Topps scored with two out of the three players. Bell struggled through an unproductive year (his last in Cincinnati), but Pinson and Robinson became a more finessed version of the “M and M Boys,” Mantle and Maris. Thanks in large part to Pinson and Robinson, the Reds won 93 games to capture the National League pennant. Robinson batted .323 with 37 home runs, while Pinson contributed a .343 average, the best mark of his career. Heavy artillery indeed.

As well as Robinson played in 1961, he would achieve his absolute peak in 1966, the year that Topps produced a card designating him as a Baltimore Oriole even though he is clearly wearing a Reds uniform. This is the only Topps card that shows Robinson capless, revealing his high forehead. Also evident is the stern Robinson stare that would become his trademark. Outside of Bob Gibson, no one could flash a more serious look than F. Robby.

The capless card allowed Topps to account for his change of address during the 1965-’66 offseason. Reds general manager Bill DeWitt, who felt that Robinson was “an old 30” and “a fading talent,” and believed it was smart to trade a player one year too early, rather than one year too late. In this case, DeWitt should have waited. Robinson would unleash terror on the American League in 1966. Not only did he lead the league in all of the Triple Crown categories, but he also outpaced everyone with a .410 on-base percentage, a .637 slugging percentage, and 367 total bases. He did that all despite stretching the tendons in his knee during May. Robinson spent the rest of the season in pain, but with little effect to his hitting. He sat out only seven games all season.

Robinson would remain with the Orioles through the 1971 season. In a move that shocked some Orioles fans, the team traded him at the famed 1971 Winter Meetings, sending him to the Los Angeles Dodgers for four players, including a young Doyle Alexander. The trade explains the presence of two full-fledged Robinson cards in 1972. (And to be accurate, Robinson appears several other times in ’72 Topps, including a card depicting the 1971 World Series and several “league leader” cards.) The standard issue shows him during spring training in 1971, sporting the old windbreaker-under-the-jersey look, his face glistening with perspiration. I love the way that Robinson playfully points his bat toward the photographer, a classic pose for a slugger.

Later that summer, Topps debuted its first subset of “Traded” cards. The small grouping of eight cards included an updated card of Robinson, now wearing his new uniform: the road grays of the Dodgers. All these years later, it still seems weird seeing Robinson wearing Dodger Blue. Of all of his uniforms, this one seems like the oddest fit, almost surreal in a way.

Robinson played only one season for the Dodgers. First off, he didn’t see eye to eye with his old school manager, Walter Alston. His play also suffered, but it wasn’t the Dodger Stadium pitching environment that did him in; Robinson actually put up better numbers at Chavez Ravine than he did on the road in 1972. At home, Robby posted an OPS of .917, but the number fell to .701 away from Dodger Stadium.

Technically, Robinson would wear the Dodgers uniform on one more card: his 1973 Topps release. But Topps did its best to create the illusion that he was wearing the uniform of his newest team, the Angels. The Topps airbrush artist wiped out the word “Dodgers” from the front of the uniform, giving his plain white jersey a more generic look. The ’73 card also represented the first time that Robinson shared one of his regular issue cards (and not a combination card) with another player. The Philadelphia catcher at the edge of the card is burly John Bateman, who took part in the action in a game played at Dodger Stadium on July 22, 1972.

The listed position on Robinson’s 1973 card also turned out to be deceiving. In actuality, he would make only 17 appearances as an outfielder with the Angels that summer. He spent most of his time (127 games) as the Angels’ DH, in the first year of the controversial rule.

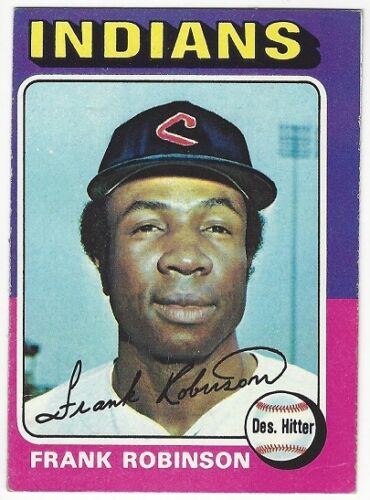

Two years later, Robinson would appear on his final regular Topps issue. By now, he was a DH for the Cleveland Indians, who had acquired him in a trade during the 1974 season, necessitating airbrushing an Indians cap over his California colors. (Robinson’s face looks a little puffier here, a natural occurrence given that he was now in his late 30s.)

More significantly, he was now the game’s first black major league manager. He was well prepared for the job, having managed several seasons in the Winter Leagues, where he drew praise for his tough but fair approach, and his ability to teach. For some reason his 1975 Topps card, with those wonderfully colorful borders, does not include the designation of “manager.” It lists him only as the “Des. Hitter.” The Indians’ team card would include a small corner photograph of Robinson, listing him as manager, but Topps lost out on an opportunity to call attention to the historical significance of the situation on Robinson’s main card.

As a first-year manager, Robinson guided the Indians to a respectable record of 79-80, an improvement of three and a half games over Cleveland’s 1974 performance. It was a tumultuous season, however, marked by frequent confrontations with umpires. As fiery as a manager as he was as a player, Robinson brought the same intensity to managing, resulting in three ejections (and numerous arguments) in 1975. In later years, Robinson would calm his emotions, remaining old school in approach, but more patient with the decisions of umpires.

Robinson returned to the Indians as their player/manager in 1976, this time leading the club to an-above .500 record of 81-78. Curiously, Topps did not include Robinson on a player card that summer, even though he had appeared in 49 games the previous season. I’m not sure why. It seems like a strange omission, given Robby’s status as a legendary player. In contrast, the SSPC Company, which issued a set of cards in 1976, did include Robinson as part of its inaugural set.

Not including the SSPC entry, Robinson appeared on 20 regular issue player cards put out by Topps, in addition to the aforementioned combination cards and numerous leader cards. From his days as a skinny outfielder who was nicknamed “Pencils” because of his thin legs, to his time as a history-making player/manager, the selection of cards gives us a peek into a lengthy and storied career.

These cards are another good way to remember the contributions of one of the game’s most important figures.

You forgot another tidbit in the “diehard fan’s” memory bank: Robinson was a notorious plate crowder, having led the league in HBP 8 times. Also, the nickname The Judge started in 1969 when the Orioles were coasting to a 109 win season and had time for some levity in the clubhouse. Robinson held “court” after each victory and fined players for trivial transgressions all meant in good humor. Needless to say, his “court” never held sessions during the ’69 series debacle.

Great retrospective on a GREAT player. RIP, “Judge.”

My father, who was born in 1923 and a baseball fan his entire life, had a simple way of evaluating hitters. Whenever I’d mention the sensation of the day — whether it was Reggie Jackson and Rod Carew or Mike Schmidt and Wade Boggs, my father would inevitably reply “He’s pretty good…” (pause) “… but he’s no Frank Robinson.”