Catfish and Me

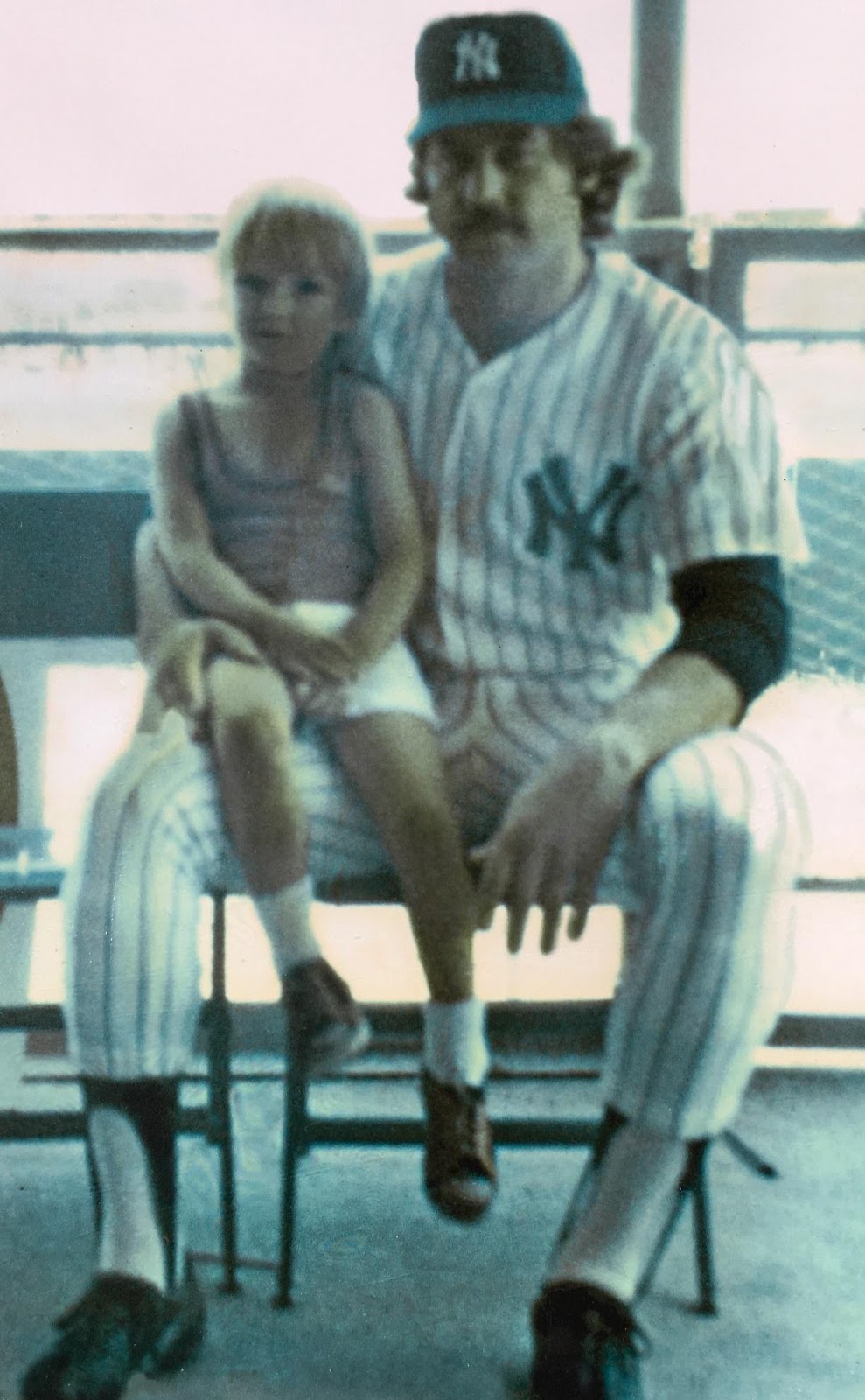

A late-career signing made it so one fan would have an unforgettable moment with Catfish Hunter. (via Jimmyack205)

My mother was nervous. Not anxious or excited nervous, but the kind of nervousness you feel when you find yourself trapped in a situation you know probably won’t end well. She didn’t tell me she was uncomfortable, and I had just turned five years old, so I couldn’t parse exactly what was wrong. Still, I had a general sense something wasn’t quite right.

But we were not leaving. That much my mother made clear without speaking.

We were standing in line in what had been an orderly fashion to that point. But it was crowded, and there were a lot of people there who had been waiting in a lot of lines with growing levels of impatience. And despite the weather being beautiful – 75 degrees and sunny – many of the 37,387 fans who would arrive that day were already there. Tensions — and presumably alcohol intake — were beginning to run high.

The Yankees were hosting the Boston Red Sox. If you have never attended a Yankees vs. Red Sox game prior to 2004, I can tell you they weren’t the bro-hugging love fests that many call a “rivalry” today. Hell, I’ve seen more personal animosity at beer league softball games than the current group of Yankees and Sox provide. Prior to ‘04, the environment rarely got below DEFCON 4. But on this particular day the Red Sox, led by three future Hall of Famers, were in the process of overtaking the Oakland A’s as the powerhouse in the American League. They were in first place — eight games ahead of the unfortunate Yankees, who had come into the 1975 season with high expectations.

Different folks handle being in line for extended periods in different ways. Some look straight ahead and blink quietly. Some resort to banality, making small talk about the weather or politics. (Gerald Ford was President on this particular day, so the weather was more than likely the number one conversation starter.) Some talk out loud about the horrors they are enduring of having to wait, as if no one else within the sound of their voice is suffering the same pain — pain now aggravated by the vocal narcissist’s behavior.

For teenage boys, some form of roughhousing is typically the response to waiting and the subsequent boredom. Pushing. Shoving. Slapping. Amateur Sumo wrestling. Basically, just general tomfoolery that in and of itself is rarely a problem. You know, kids being kids stuff. That is, until ego arrives and the playful antics deteriorate into more serious posturing with more serious levels of pushing and shoving. You know, the point where a parent is needed to settle everyone down or this could go sideways.

As luck would have it, a group of teenage boys, who were having just that kind of shoving match, were in line right behind my mother and me.

My mother picked me up to get me out of the way of the bodies being shoved, which wasn’t easy. I was a small kid, but I still was five – not an infant. She could’ve yelled at them, but this was NYC, 1975, and they were five or six teenagers. My mom was a 28-year-old woman with a kid in her arms. She could have tried to ignore it, but she had already been nudged into once and saw me take a bump from being too near the “play” scrum.

It wasn’t quite DEFCON 4, but it sure wasn’t the fun situation my mother had planned for us that day.

***

If you’re reading this, then there’s a better than average chance that you know of James Augustus “Catfish” Hunter and know at least most of the stories:

Born and raised in North Carolina, as a kid he was accidentally shot in the right foot by his brother in a hunting accident, costing him a toe and leaving him with shotgun pellets lodged in his foot. He went on to be signed by the Kansas City Athletics’ owner Charlie Finley as an amateur free agent on June 8, 1964 at the age of 18. Ole Charlie gave Jim the nickname “Catfish” for no other reason than Finley felt Jim Hunter wasn’t a flashy enough name.

The newly dubbed “Catfish” was on a big-league mound less than a calendar year later pitching for the Athletics versus the White Sox at age 19 in front of a crowd of 2,025 people in Chicago. That’s if 2,025 people in a baseball stadium can be called a crowd. He threw two innings in relief of what was to be a 6-3 loss for the Athletics, with former Yankee great Bill “Moose” Skowron being one of his two strikeout victims.

Three years later he pitched a perfect game against the Minnesota Twins, whose first four batters that day were Cesar Tovar, Rod Carew, Harmon Killebrew, and Tony Oliva. That is what pitchers refer to as a “handful.” And in addition to getting the first four killers and the rest of the Twins out at every turn at bat, Catfish also drove in three of the four A’s runs that day. (“Ron Bloomberg, who?” I ask.)

From 1970 through 1974, Catfish lead American League starting pitchers in wins, winning percentage, left on-base percentage and WHIP. He was also second in innings pitched, fourth in strikeouts, fourth in shutouts, fifth in adjusted ERA, fifth in strikeout to walk ratio, and ninth in fWAR during that stretch. During that five-season stretch, he pitched in four All-Star games, won a Cy Young award and finished in the top four in the Cy Young voting three other times.

Simply put, in an era that had more great starting pitchers than perhaps any other era — 12 future Hall of Famers averaged at least 190 innings pitched per season over that time span — Catfish was one of the best.

What you may not know is that Hunter was also major league baseball’s first free agent and that success in a battle with ownership gave baseball union chief Marvin Miller the opportunity to test a league-wide free agency system with the baseball owners shortly thereafter.

Years before, scout Clyde Kluttz of the Kansas City Athletics scouted Hunter and as both a former player and fellow North Carolinian, taught Hunter the responsibility of handling money in the fast-lane life of major league baseball. A’s owner Charlie Finley, after going to North Carolina to watch Hunter pitch personally, signed him for $75,000. Finley wanted his prospects to have colorful nicknames, so he made up a story about Hunter disappearing as a youth and being found with two catfish as he was reeling in a third. Many still believe the story.

Not too long after Catfish’s career began with the A’s, Finley offered Hunter a friendly loan of $150,000 — Catfish had his eyes on a large piece of land in North Carolina but didn’t yet have the money for it. Finley offered to front the money for him as a favor and they agreed on repayment terms: $20,000 per year plus 6% interest.

The friendly routine worked out great until a few months later, when Finley demanded all the money back, knowing full well that Hunter no longer had it after recently buying the land. Worn down by Finley’s verbal abuse and constant badgering, Hunter, not wanting to jeopardize his major league career, sold the majority of the land back – at a loss – to repay Finley. Needless to say, Finley’s inclination for not honoring deals was something that was not soon forgotten.

Fast forward a few years. Hunter’s 1974 contract with the A’s had a wrinkle: $50,000 of his salary was to be put into a deferred annuity to be collectible in 10 years. The stipulation was that the $50,000 would be paid to a North Carolina insurance company – not Hunter himself – over the course of the season. Again, this worked out great – until Finley realized the payments would not be tax-deductible on his end. So he never made them.

Hunter’s lawyer began a threatening letter-writing campaign to Finley and the A’s, which went largely ignored. As the season wore on, Miller and the player’s union became involved, explaining to Finley that failing to disperse salary was not only illegal but a breach of contract. Meanwhile, Hunter was having his best season on the field, and would soon benefit from the leverage that his performance would provide.

By September, and with the patience of all involved running out, Miller demanded to MLB that the payments be made forthwith or the contract be terminated immediately. Finley’s response was to offer Hunter the $50,000 in one payment, directly to him.

Not the deal, said Catfish, now with the hammer of leverage. The money should have been going into an annuity all season long.

Marvin Miller and the player’s union declared the contract in default and asked MLB to declare Hunter a free agent. After an arbitration hearing, MLB arbiter Peter Seitz came down on the side of the union, and Jim “Catfish” Hunter was officially a free agent – baseball’s first.

Later in the winter of 1974, Catfish agreed on numbers and contract terms in principle with the San Diego Padres. But Gabe Paul of the New York Yankees and old friend Clyde Kluttz, who had become a scouting director for the Yankees, convinced Hunter that New York City was THE place to play, even for a country boy.

When Padres owner Ray Kroc asked Catfish to do radio and TV ads for McDonald’s, which Kroc owned, Hunter decided that the Yankees would be the team to benefit from his considerable skills. In exchange, he would receive a $1 million bonus, $1 million in life insurance, $750,000 in salary over five years, $500,000 in deferred money, $200,000 for attorney’s fees, and $50,000 for each of his two kids’ college funds.

But more importantly, Marvin Miller now had precedence for free agency. Soon after the Catfish saga, Andy Messersmith and Dave McNally had issues with their contracts, and Marvin Miller used them to make free agency part of the collective bargaining agreement.

The rest, as they say, is history.

***

Catfish made his Yankees debut against the Detroit Tigers on April 11, 1975, at Shea Stadium in front of 26,212 fans.

Yes, Shea Stadium, the home of the New York Mets at the time. There was a stretch from the late 1960s through the mid-1970s when New York City was a Mets town. The Mets had appeared in two World Series, winning one, and were on a pretty good run. The Yankees, suffice to say, were not.

Part of the plan to reinvigorate the Yankees franchise was to reinvigorate Yankee Stadium. As a result of the ambitious construction project, the Yankees played the 1974 season in the Mets’ home and started the 1975 season in the same locale with “YS II” to be open for business in 1976. We can only imagine what the Boss’ mood was while his Yankees called Shea “home.”

Hunter didn’t pitch well that day, nor over his next three starts. After four starts, he was 0-4 with 21 earned runs allowed in 25 innings pitched as a Yankee. Then he went back to being Catfish.

Over his next 20 starts, he would pitch 173 innings, and win 13 games while posting a 2.13 ERA. I’ll pause while you re-read that: 173 innings, in 20 starts.

In the middle of that stretch, not only did he earn a berth on the American League All-Star team, but on Father’s Day was honored as “Sports Father of the Year for 1975” by the National Father’s Day Committee. In full disclosure, the latter of those two honors loses some luster when one learns that Babe Ruth was a previous recipient of the award.

In addition to revamping their stadium and getting better players, one of the ways the Yankees tried to be more appealing and fan-friendly was to hold an annual picture day. Today, this may seem weird, but the idea was to get most, if not all Yankee players to take pictures with fans. Each fan would get a Polaroid picture with him or herself with a Yankee enclosed in a small folder shaped like a baseball. Admittedly, it was pretty cool.

The only caveat was that, in an effort to keep orderly, well-maintained lines of more or less the same length, fans would be escorted to a particular player’s line depending upon its current length. So one might have ended up on Graig Nettles’ line, Bobby Bonds’, Fred Stanley’s or Sandy Alomar’s. You didn’t get a choice.

My parents took me to the 1974 picture day, where my then-recently four year-old-self got my picture taken with Tippy Martinez. I sat on a metal folding chair about a foot away from Tippy on his own metal folding chair, although it seemed like five feet. Other than the photographer saying smile, no one spoke. Neither Tippy nor I smiled. I remember thinking his legs were enormous; other than that I don’t think we even looked at each other.

On this day in 1975, then, I was prepared to be underwhelmed. Gerald Ford was President and “The Hustle” was the number one song at the time, so most folks were used to the feeling. But it was still kind of cool for a five-year-old baseball fan, as well as for my mother, who was a decades-long Yankee fan herself. Like most people, my father had instilled the love of baseball into me through playing, story-telling and in-game explanations. But my mother also would tell me how she used to take the train to the Stadium in the ’60s to see the Mick. So seeing her son with a real-life Yankee up close certainly had her excited.

My mother was even more excited when she realized that we had been ushered into Thurman Munson’s line. Thurman was the best player on the team and was going to be the centerpiece of the Yankees’ return to glory.

The excitement turned to disappointment pretty quickly, as an announcement was made that all players who were in that day’s starting lineup needed to leave to get ready for the game, and the fans on those players’ lines would be shuffled elsewhere.

I’m not sure if we waved goodbye to Thurman. I am sure that’s when my father’s patience for waiting ran out along with that of many other fans who thought getting to their seats and grabbing a beer (or two) and a hot dog (or two) was a better option than to wait and see whose line we were in.

But luck was on our side that day: We weren’t brought to the line to meet and get a picture with Alex Johnson or Walt Williams, all due respect to the Johnson and Williams families. We were ushered to the line with Jim “Catfish” Hunter on the end of it, the seven-time American League All-Star, the reigning American League Cy Young award winner, and the leader of the pitching staff who was supposed to return the Yankees to their pennant-winning ways.

***

Although the herd was thinned by some fans leaving their places in line to do some combination of hydrate, watch on-field pregame activities or find their seats, what remained of the herd had become short on what patience remained.

Someone yelled an obscenity-laden directive at the now overly rambunctious teenagers. One of the teenagers returned verbal fire, mumbled under his breath, of course. Something was said back. The physical activity slowed, but the tension rose, as most wondered if this was when things escalated to a point where security would be needed.

There was no security personnel within sight, though. My mother, who was and still is a patient woman, noted the lack of security presence under her breath but loud enough for me to hear. When she put me down, I remember thinking this was the end of picture day for us.

But before we moved, a stadium employee who had presumably been near the front of the line and out of our sight, moved toward us. When he got within a foot or so of my mother and me, he stopped and looked back in the direction of the front of the line. He pointed at us while quizzically looking back at someone at the front of the line and out of our sightline, as if looking for confirmation. Apparently, he received such confirmation and told my mother and me to follow him.

As we started walking toward the front of the line, passing everyone else who had been waiting, the stadium employee said to us, “He saw you struggling and asked us to help you out and bring you up front.”

We got to the front of the line and saw that “he” was Catfish. One arm extended, palm up, motioning to me to join him. There I was with an All-Star, Cy Young-winning pitcher sitting in a metal folding chair with an empty one next to him, ready for me.

I walked over to the empty chair and jumped on it to sit as I did the previous summer with Tippy. And again, I felt a million miles away from everyone – but this time it was only for a moment. Catfish scooped me out of my chair and propped me up on his lap. Four and a half decades later and I can still remember the thought that went through my head: “This is really cool – a big-league pitcher and a nice guy, too.

After the photographer took our picture, I got off Catfish’s lap as he smiled at me. I’m pretty sure I didn’t say anything. A few seconds later I got my Polaroid with the two of us in a baseball folder and we were off on our way.

***

The Yankees lost to the Red Sox that afternoon, 4-2. Three future Hall of Famers would lead the way for the BoSox as some guys named Fisk, Rice, and Yastrzemski all drove in and/or scored runs. Catfish would start the next day and throw a complete game with no earned runs allowed, and take the loss (…?). Boston’s Bill Lee also threw nine shutout innings that day, but his shortstop didn’t make an error to put the eventual winning run on base – Hunter’s shortstop did.

Hunter would continue his great ’75 campaign for the Yankees, going 8-3 with a 1.88 ERA over his last 11 starts. For the season, the first for the North Carolinian in New York, he would lead the American League in wins with 23 (his fifth consecutive season with at least 20), complete games, innings pitched, WHIP and hits allowed per nine innings. A typically great season from Jim Palmer would be the only thing that kept Hunter from another Cy Young award. His 8.1 Wins Above Replacement that season was the best for a Yankee pitcher since 1937.

The Yankees would win 83 games in 1975, finishing in third place. But the groundwork for the return to glory was laid down as Hunter, along with some other names you’d recognize, made three World Series appearances and won two World Series championships in the following three seasons.

Suffering from both chronic shoulder pain and the side effects of diabetes, Hunter retired after the 1979 season. He would eventually be inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1987, along with the Cubs’ Billy Williams. After a battle with ALS, Catfish passed away on September 9, 1999 at the age of 53. If, like me, you’re of a certain age, this is a somewhat disconcerting fact.

I recall my meeting with Catfish more nowadays than I used to. Maybe my own senescence has brought about more feelings of nostalgia. Perhaps the recent passing of my father makes me think of baseball memories more often, and causes my mother and me to reminisce more often. And we invariably reminisce about what may have been a small gesture that day in 1975, but one that meant the world to us. Whatever the case, it’s a great memory for me of a great pitcher, a great Yankee, and a great guy.

These 44 years later, I wonder if I’m making too much of an adult who just simply acted like a considerate adult. But in today’s era of “Let the kids play,” when “play” to a certain extent can mean make it about oneself while taunting an opponent, Catfish is a pleasant reminder that even Hall of Famers can make it about someone other than themselves.

Huge thanks to John Helyar and his great book “Lords of the Realm” for much of the background included here.

Jon,

Great article. Thank you for writing and sharing.

I was a Yankees fan, and Catfish fan as a youth until he retired because of his diabetes. As a 10-year old diabetic who dreamed of pitching at Yankee Stadium, had a hard time accepting his retirement.

Thank you – yes, it was tough to see him go.

Nice article Jon, thank you, brought back a lot of memories of that time period.

Thank you, glad you liked it.

That’s great story . Always liked Catfish the picture is priceless! I guess we all have some great memories of baseball which keeps our love of the game last. Thanks for sharing.

Thank you, Frank, glad you liked it.

Wonderful article, thank you!

Thank you, glad you liked it.

Excellent article, Jon!

Great personal story about your picture with Catfish. Such a humble and talented player, and a kind gentleman! I had the opportunity to follow him with the Oakland A’s during the 1960’s and 1970’s, and your article brought back a lot of great memories. Our family was lucky enough to attend a few games at the Oakland Coliseum, usually on half price Monday games, when the crowds would still be under 10,000. You also provided a lot of contractual nuances and did a good job framing the historical significance of Hunter’s free agency. Thanks for the great reporting!

Thank you – wow, that must’ve been some time at the games in Oakland in the early 70s!