Demographic Ball

Might a young player like Aaron Judge one day find himself in the record books? (via Arturo Pardavila III)

Do you remember record chases? Will Alex Rodriguez pass Hank Aaron? Or will it be Ken Griffey Jr.? Oh, right, Barry Bonds. How many strikeouts can Randy Johnson get? Can he pass 5,000? Can he challenge Nolan Ryan? And hits and wins and doubles and saves and on and on. Sure, they didn’t generally happen, but we entertained the notion.

Now, quickly, name a player who you think has even a ghost of a chance of breaking a major record. Albert Pujols isn’t going to make it. Neither will Miguel Cabrera. Mike Trout isn’t a compiler in the way he’d need to be. Clayton Kershaw isn’t going to get the innings he needs.

There’s no one. There aren’t even that many candidates to join the 3,000-hit club or the 500-homer club. We’ll have some pitchers get to 3,000 strikeouts, but not much over it.

I was looking at the record books recently and looking at the active players and wondering if maybe we are done seeing record chases. Maybe, I thought, the game has changed enough in the way players are used and evaluated that we aren’t going to see great compilers anymore.

My thinking was that players weren’t being allowed to hang on once they ceased to provide value in an overall sense and that this was probably different than in eras past when, I thought, players might play forever if they could still hit 30 homers. That, paired with the reduction in PEDs, which prolonged careers, I reasoned, may have permanently altered the record-breaking landscape.

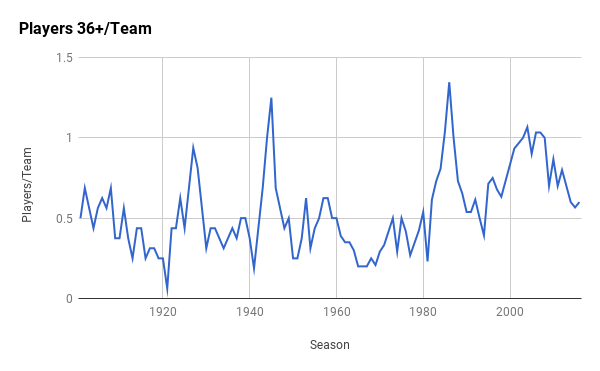

There’s a reasonably simple test for this. I went through baseball history and–starting in 1901–recorded how many players there were on a per-team basis who were at least 36 and got at least 200 plate appearances. Basically, old guys getting regular or semi-regular playing time. I then made a line graph. (I’m an English teacher, so please appreciate how special that is.) Here is said graph:

That’s a weird graph. I thought I would see a general decline in older players with maybe a spike during the PED era. But that’s not what happened at all. There are four notable spikes, late 1920s, mid-’40s, mid-’80s and the (sinister music) early 2000s. The spike in the ’40s, one presumes, is result of World War II, and the most recent spike is the PED era. But the other two had no explanation I can think of.

While I was aware random variation was possible, I went looking for explanations anyway. Demographic trends could explain some of it. Baby Boomers hit their late 30s in the ’80s. After the 1890s, population growth in the U.S. declined dramatically, which could explain why players were able to hang on in the late ’20s: because there wasn’t as much competition. Even the PED era syncs up with the children of Baby Boomers reaching their late 30s.

Which isn’t to say I had faith in this particular explanation. But the appearance of the spikes told me something about compilers. Though there were obvious exceptions, many of baseball’s great compilers finished their careers during the spikes. For instance, five of the 24 pitchers in the 300-win club got win No. 300 between 1982 and 1986. And seven of the 27 members in the 500-home run club got to No. 500 between 2001 and 2007.

Because of this, it mattered whether the spikes were random or had a direct cause. If they were random, we could expect another one (and thus another bunch of big, fancy numbers) at some random moment in the future. If each spike had a direct cause, then we’d need to have something happen in order to get another spike.

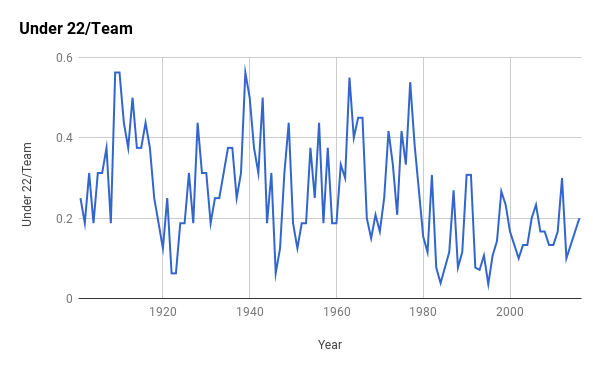

I mulled this for a while and decided the next step was to look for the prevalence of extra-young players. After all, to hit the kinds of numbers I’m looking for, a player needs to play into his late 30s, but he also needs to start pretty young. Here then is a chart showing the number of players per team who qualified for the batting title and were 22 or younger.

This is a bit more sporadic than our first chart, but interestingly, you can see some points that correspond to data in the earlier chart. Note, for instance, that young players crater in the ’20s and ’40s. There are peaks of young players in the 1900s and 1960s that correspond to the old-player peaks that occurred 15-20 years later.

Expansion years matter a lot here, as well. They thin out the talent pool and force young players into the majors earlier. It’s also interesting to note the peak in the late ’30s that didn’t have a corresponding old-player peak 15-20 years later. World War II took a huge toll on MLB (and on the country as a whole) that is apparent in a number of ways that really show up in a granular way as well as the more well-known losses of seasons among some of baseball’s greatest players.

What’s really stands out in this second chart, however, is what happened in the early ’80s when young players were suddenly getting shots only about half as often. What happened, you may already have figured out, is free agency. Teams couldn’t afford to let players grow into roles, so unless they were sure things, they weren’t given the opportunity. And I can tell you from looking that the names you see among the young players for those years tend to be Hall of Famers or players who would have been but for injury or other extenuating circumstance.

And so, I’m back to my original question: Does the current calculus used to evaluate if a player should be in the majors allow for players to reach the milestones we all grew up paying attention to? I don’t know.

Things are certainly more different now than they’ve ever been before. PEDs largely have been filtered out, which reduces the prevalence of older players. Free agency means many have to wait longer to get a shot. Neither of those is good if you’re looking for the next 300-game winner or 500-home run hitter.

However, the young players who do get shots also tend to be fantastic. Teams, seemingly, aren’t afraid to promote players like Mike Trout or Albert Pujols who force the issue, so while the demographics of baseball have narrowed in a general way, they may not have narrowed in the ways that matter for record chases and milestones. I guess I’ll check in with you in 15 or 20 years, and we’ll see what happened.

Interesting article Jason.

Couple of hypotheses:

1) Spike in the 1980s a result of both expansion in the mid-70s (Blue Jays and Mariners) as well as the DH rule, which allowed older hitters to hang on. For the pitchers, that was also when 4-man rotations became 5-man rotations, allowing older pitchers (Blylevin, Seaver, Sutton, Carlton etc.) to hang on.

2) The 1920s spike likely to be the result of the spike in offense, which masked older hitters declining in skill with greater raw offensive output.

Nice, easy to read article from an English teacher. Imagine that. LOL. The last paragraph sums up my observation as well. The young players who were brought up in the last couple of decades were the can’t miss, great players. But I also think that baseball is again becoming a younger man’s sport. Time will tell, as you say. Of course, wins are less prevalent and homers are more prevalent in today’s game. That’s probably another article to write…

Interesting age breakdowns and comments. Regarding that underlying perception, “if maybe we are done seeing record chases,” perhaps, instead, over the past generation or so, we have seen those milestones passed more frequently than what used to be usual in MLB.

For example, of the 30 players with 3000 hits, 14 of them reached that milestone in just the past 25 years. It took 90+ years for the first 16 players to reach that mark. Of the 27 players with 500+ HRs, nearly half of them (13) reached that milestone only since 1996. Bob Gibson retired in 1975 as only the second MLB pitcher with 3000+ strikeouts; 14 more pitchers have crossed that threshold since then.

Perhaps, rather than being done with record chases, we might simply be nearing the end of an upward spike in players reaching those milestones, presumably in relation to the variables you mentioned. The past two decades or so might be the outlier, rather than the rule, and maybe in the recent generation we might be taking some longevity-oriented accomplishments a little bit for granted.

While it’s easy in the Advanced Metrics Era to emphasize the limitations to a milestone such as 3000 hits, and to dismiss certain players who approach or pass 3000 hits (or 4300 hits+BB+HBP) as merely being compilers (especially since many players have declining skills by the time they approach the number), nonetheless a player has to have been very good, over a very long amount of time, to reach the milestone.

Could the author explain what is PED?…just to undestand the point…

Performance enhancing drugs.

Hm. I think the traditional pitching benchmarks and the traditional hitting benchmarks are different stories.

Starting pitching norms and pitcher health management have changed to a degree that 300-win careers are close to extinct, and certainly records around complete games or shutouts are beyond safe. For pitching, the general public might need to start glorifying rate stat thresholds more and traditional counting stats less.

Are we sure much has *really* changed on the hitting side? Ichiro just hit 3,000, and at least three more players have a strong chance to eclipse it in the next 2-3 years (Beltre, Pujols, Cabrera). Cabrera should top 500 home runs as well. With good health, it’s hard to imagine young stars like Trout, Harper, Lindor, Correa, Betts and others not also entering some of these conversations in a few years.

Nice article, Jason.

I would echo the comments of Carl about expansion and the shift to a five-man rotation. And like Kyle said, the nature of pitch counts makes it unlikely the records for career complete games, shutouts and wins will fall.

I would add that other factors that began around the same time (60/70s) to raise the age of rookies are:

(1) more players forgoing amateur free agent signings and, instead, attending and completing college.

(2) the advent of free agency in the majors at the end of the 1976 season.

General managers became less reluctant to cut ties with a player on a guaranteed three-year contract to call up a 21-year old rookie from AAA because he’d still be on the hook for the veteran’s salary. Doing otherwise would also draw even more attention that he made a poor decision to sign the over-the-hill veteran to a lengthy expensive contract.

As for Hank Aaron’s career home run record (he still holds it, right? wink), keep in mind that a few events prevented Ruth’s record from falling earlier, perhaps multiple times. Namely that being World War II and the Korea War.

Ted Williams would have very likely broken the record if in addition to the career numbers he did put up added five more seasons to his career in his prime. It would have been close, possibly in 1960. I can certainly imagine his last at-bat home run being #715. Or maybe it’s #714 and then he plays in the Red Sox road trip to… Yankee Stadium. Maris heard boos for hitting #61 there. Can you imagine the outcry by Yankee fans to see a Red Sox star break the Babe’s career record in the “House That Ruth Built”?

And if Williams fell short of the mark in 1960 (he did hit 29 home runs that year), with expansion in 1961 it’s probably a lock that he plays.

And then what? What if the Giants had moved to Minneapolis instead of to San Francisco? Wouldn’t that have helped Willie Mays? He did hit 660 after all while nonetheless playing in the pitching-dominant 60s (as well as losing some time to military duty). So it’s not a stretch at all to see Mays be the one break Williams’ record.

Then Aaron would have broken Mays’ record.