Examining Potential MLB Expansion Cities, Part 1

The Expos left Montreal in 2004. Could MLB return there at some point? (via Mike Durkin)

To commemorate Rob Manfred’s taking over as Major League Baseball’s 10th commissioner, we ran a series of articles giving Manfred suggestions on ways to improve the game during his tenure. One of these suggestions came from Jeff Zimmerman, who called for an increase in the number of teams from 30 to 36.

Zimmerman made some convincing arguments in favor of a need for expansion. He observed that expansion has stopped happening, with the number of teams staying steady while the pool of players to draw from has continued to grow. Additionally, he notes that league-wide run scoring increased the last four times MLB expanded. Adding more teams might help cure baseball’s declining run scoring.

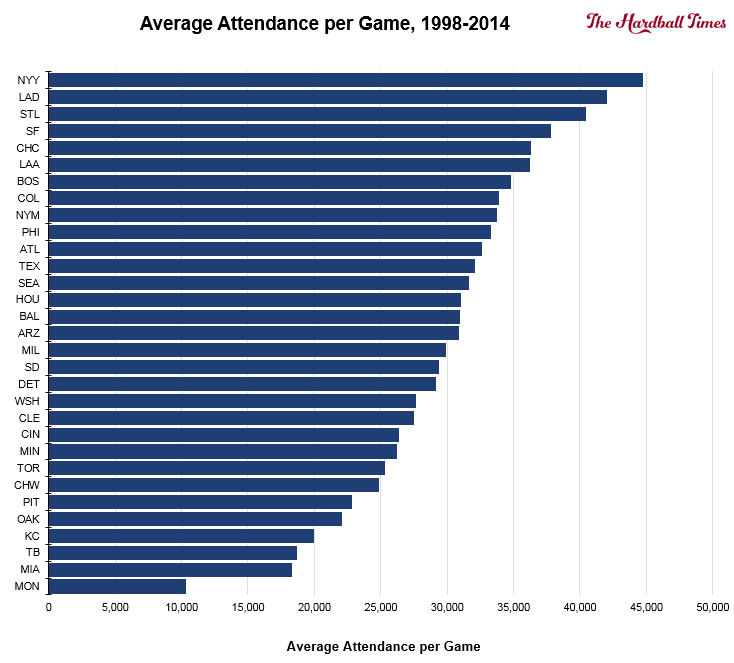

If Manfred and Co. do in fact decide to increase the number of teams, they’ll need to find cities to support these new franchises. Recent history suggests this is no easy task. Major League Baseball added four clubs since 1993, and two of them — the Miami Marlins and Tampa Bay Rays — have struggled mightily to get butts in the seats. In fact, these two teams have brought up the rear in attendance numbers ever since the Expos left Montreal.

The Marlins’ low attendance figures can be blamed — at least in part — on the penny-pinching ways of Jeffrey Loria, who has a habit of alienating fans by holding bi-decade fire sales. But what about the Rays? They’ve been in the playoff hunt just about every year since 2008, and have a .552 winning percentage over this period — fourth best in baseball. Still, their attendance figures have been among the game’s worst. In the last three years, they’ve ranked 30th, 30th and 29th. The dilapidated state of Tropicana Field surely plays a role in inhibiting the Rays’ attendance figures, but that can’t be all that’s going on.

There are surely other factors that differentiate a city like Miami from, say, Milwaukee, which draws nearly twice as many fans despite having roughly one quarter as many people living in its greater metro region. But what else comes into play?

To get at this question, I built a regression model considering recent seasons for teams from Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSAs) that have exactly one team. I set average attendance for home games as my dependent variable, and considered a broad swath of variables for my independents. Some had to do with the team itself, like recent win-loss records and new stadiums. Unsurprisingly, having won a lot of games recently and opening a new stadium both result in an attendance bump. But including these variables was more about zeroing in on the less-obvious factors that drive attendance: Those that deal not with the team, but with the team’s home city.

Before I go any further, I’d like to make one technical note. When I use the word “city” here, I’m actually referring to that city’s greater Metropolitan Statistical Area, and not the city proper. For example, “New York City” refers to not just the five boroughs, but also much of the surrounding area, including Long Island and part of New Jersey.

In building my model, I did some out-of-sample testing to determine which variables to include in my final iteration. In other words, I built a few potential models using 60 percent of my data, and tested them on the remaining 40 percent to ensure I wasn’t overfitting the data. Somewhat surprisingly, a city’s population size did not make the final cut in my model. I’m thinking this has something to do with the selection bias in my sample: All large cities have a major league team, but perhaps many of the small cities with relatively poor attendance-drawing abilities aren’t in the sample. Population size is obviously a factor, but it’s just not accounted for in my model.

When it was all said and done, and the regression-induced dust had settled, I came away with 23 variables. These variables returned a respectable .76 R^2 coefficient. I’m not going to bore you by trying to explain every one of these variables, but will instead provide some key takeaways as to what characteristics make a city well-suited to draw fans to a big league ballpark. Here’s what I managed to uncover, ranked roughly in order of importance:

1) Cities with higher incomes and lower levels of poverty draw more fans

This one is pretty straightforward. Well, the explanation is, at least. My model includes five income-related variables of differing importance, but the bottom line is that high-earning cities do a better job of generating attendance. This isn’t surprising. If residents have higher incomes, they have more money to spend on goods and services, including buying tickets to baseball games. Simple as that.

2) Cities with a higher percentage of black and/or Hispanics/Latinos draw fewer fans

Before I dive into this one, a bit of a technical clarification is in order. (Last one, I promise.) The U.S. Census Bureau considers race and ethnicity to be two different things, meaning census takers are asked to identify both race (based on physical appearance) and ethnicity (based on ancestry). This means that a person can identify as white and Hispanic or black and Hispanic, etc.

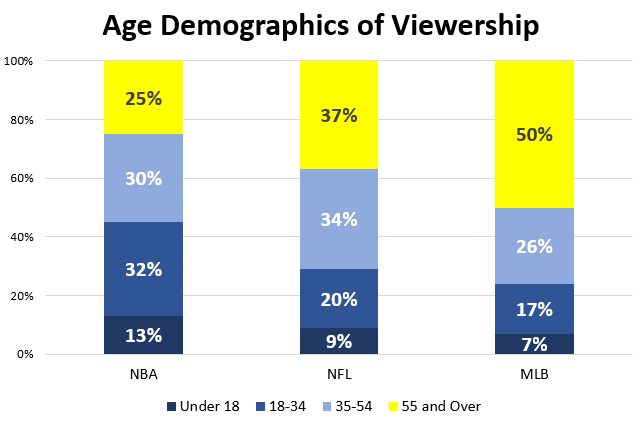

Now, on to the significance of a city’s racial and ethnic demographic. It’s been well documented that black players are underrepresented in the majors. So it’s not at all surprising that they’re underrepresented in baseball’s fan base as well, especially relative to the other major sports.

Blacks make up just a sliver of baseball’s viewing audience, so it’s easy to see why cities with a larger share of blacks wouldn’t draw quite as well. Cities with large Hispanic populations face a similar struggle, although the effect isn’t as large.

3) After accounting for income, cities with more college-educated individuals draw fewer fans.

It’s important to remember that my model also includes variables for income, which often goes hand-in-hand with education. So what this is really saying is: Given two cities with the same income demographics, the one with fewer college grads will draw more fans. This effect is fairly substantial, but it’s hard to pinpoint exactly what’s behind it. Maybe college-educated people have a broader array of cultural interests, making them more likely to spend their incomes on things other than baseball games? Sounds reasonable, but that’s only a guess.

4) Cities with a higher percentage of males draw more fans

This one makes sense too. While there are plenty of female baseball fans, they’re far outnumbered by their male counterparts: Males accounted for 70 percent of baseball’s viewership in 2013 according to Nielsen. The average man is much more likely to be a baseball fan than the average woman, so it’s only logical that teams find more paying customers in male-heavy cities.

5) Warmer cities tend to draw more fans

Cold weather sucks. Especially when you have to sit in it for three to four hours at a time. This likely explains why cities with higher average temperatures tend to draw better than their colder counterparts.

6) Cities with an NFL team draw fewer fans, but the hit isn’t as big if the city also has an NBA team

Although I hate to admit it, football is far and away the most popular sport in America. So if there’s a NFL team in town, it will inevitably draw fans away from baseball. The second piece of this one is a little less straightforward, but I think it might have something to do with the type of city that’s able to host multiple professional sports teams. If a city has what it takes to support both an NFL and an NBA team, it’s likely well-suited to support sports teams in general, which seems to outweigh any hit caused by having an NBA team in town.

7) Cities with older populations tend to draw more fans

Baseball fans tend to be old. According to Nielsen, half of baseball’s TV viewership comes from people 55 or older, which is a significantly larger slice of the pie than in other major sports. And having a large population that is 65 or older substantially drives down attendance.

Given this factoid, it’s no surprise that cities with older populations do a better job of getting fans into the ballpark.

However, having too many people who are too old also seems to be a bad thing. This can probably be explained by the fact that younger people are more active, and therefore more likely to go to games instead of watching from the couch. No doubt, this is one of the culprits for the attendance problems faced by the teams hailing from Florida — the retirement capital of the U.S.

Now that we’ve established our parameters and takeaways, tomorrow we’ll dive in and examine possible expansion cities.

References and Resources

- U.S. Census: American Community Survey, 2013 1-year estimates; 2009-2013 5-year-estimates

- Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA)

- Weatherbase.com

- Baseball-Reference.com

- Nielsen: Year in Sports Media Report, 2013

- World Bank

- Brookings Institute: Global Metro Monitor

Really interesting article – looking forward to the list of proposed cities tomorrow and if you plan to tackle current markets only (US / Canada) or look abroad as well. Based on your criteria here are six cities I think will fare well, along with the division I would put them in and reasoning:

– Las Vegas (NL West): warm weather, largest US City without professional sports, above average per capita income.

– Charlotte (NL East): Warm weather, NFL / NBA already present, high % of college educated residents.

– Nashville (NL Central) – warm weather, significant population growth, highly educated resident base. NFL / NHL already

– Jacksonville (AL East) – warm weather, older population

– Columbus (AL Central) – highly educated population, significant population growth, above average per capita income.

– Vancouver, CA (AL West) – mild weather, highly educated population base, high per capita income.

Highly-educated populations decrease interest in baseball so some of your reasoning doesn’t make sense (chances are you just misread the article–I did at first too).

I can’t see MLB expanding to Vegas because of gambling. It seems like the NHL is willing to take that plunge, and I’d imagine that the rest of the major sports leagues will wait and see how that pans out and let hockey shoulder all the risk.

I think that Charlotte, Nashville, and Columbus are all good, logical suggestions, especially with no teams incredibly close by. I’m sure that the Mariners would not be pleased with an expansion team in Vancouver, although that would make for a great rivalry.

Columbus is a horrible location, it’s within an hour and a half drive of both the Indians and Reds, and is a college /AAA town.

Yeah, Columbus is a bad idea. A lot of Columbus’ population leaves in the summer as well. Maybe go further down the highway to Indianapolis. Personally, I’m looking for more reasons to go to Indiana. Nashville and Charlotte would work, but MLB should also consider bringing NYC back up to four teams.

Vancouver is the largest metro area listed here: area population is 2.8 million. Also, there is very little poverty, no ghetto, and a ton of money floating around. Baseball is very popular here and most of the major leaguers from Canada come from the Vancouver area. With mild winters (hey, I can grow banana plants, palm trees, kiwi fruit a bamboo in my garden) it is a very unique city. Montreal blew its chance with the expos and proved that anti- anglais french canadian couldn’t care less about baseball, only their beloved Canadiens.

Vancouver does has a high cost of living but is because we have one the highest per capita incomes in North America. BC Place stadium was build for baseball with 55,000 seats and with a few tweaks, and the fact that 320 million was spent on upgrades and a retractable roof, it is basically turnkey.

When I think of Las Vegas, I think transient of population with a “who cares” attitude. Kansas City is a nowhere city, with Columbus, Nashville half the size of Vancouver and Charlotte is also under 2 million. Where do you thing a large percent of Seattle’s fans come from. Seattle is a fickle, fair-weather friend type of city that only supports winners.

Remember the Grizzlies? They left only because the new owner wanted them in Memphis. They actually had hugh support and drew a totally different crowd, as well they outdrew the Canucks (who sellout on a regular basis) until some jerk announced that they were moving the team in a year, so fans basically told the NBA to go to hell.

Baseball would be very logical and a hugh success in Vancouver.

It is too bad that most americans know little abou their own country, let alone Canada and seem to thing we are all eskimos living in igloos.

FYI,

Vancouver has about 1/2 the film industry in North America with tons of movies and series filmed here. It is to the point where no one gets at all excited about a movie being filmed and even less excited about seeing star actors. These star actors causally wander the streets un molested or bothered by the public. Maybe it is a Canadian thing, but we just don’t get too excited abut this sort of thing. The film industry brings in hugh amounts of cash into the area.

Recently, an american friend asked me what Vancouver looked like so I mentioned about a bunch of movies he has seen and explained that they were all filmed here. Vancouver is known as Hollywood North.

Back to Baseball – Vancouver and MLB – a perfect fit.

I am excited to see if your possible cities include markets with teams already in them. Notably the Dallas/Fort Worth area, and of course a third team in the New York City region.

Fascinating article! Really enjoyable and I very much look forward to the list of cities this analysis churns out.

The major problem for any new team is tv revenue. It seems that attendance is second fiddle to this. I will not say attendance is unimportant, but the key is tv revenue. Montreal gets a lot of press lately as a potential site. It will not succeed because of tv revenue. The blue jays have emerged as the national team. Language is also a factor as the number of french speaking ball players can be counted on one hand (and note there have been several over the years), so there is always a gap between the players and the french fans. The other problem is that the border limits the growth of Montreal fan base. Vermont is Bosox territory, Northern NY, Yankees. I grew up an Expos fan and went to dozens of games and would love to see Montreal get a team, so says my heart, my head says it will not work.

States like Iowa, North/South Dakota and Arkansas come to mind. Great read!

The Dakotas?! Other than Mt. Rushmore and the Badlands, there’s hardly anything there! That may be the worst possible location in the country save for Wyoming and Alaska.

The Dakotas are seeing something of a population boom with the growth of the oil industry, but still their populations are far too small to support a team. However, the growth the oil boom has caused in OKC could make that a potential target.

1. If you haven’t bothered to work out the strange relationship between what the Census Bureau calls MSAs and what they call CMSAs, your statistical model is useless – e.g., the strange fact that San Jose is listed as a separate MSA from San Francisco and Oakland but the same CMSA, which produces nothing but confusion for people trying to understand the Northern California market.

2. Relatedly, any model of potential fan base requires attention not only to the local draw but to the extended draw – the people who come in from 60 or 100 miles away. The population densities that allow this to happen differ greatly in various parts of the country. Also some teams are more effective at making themselves “regional” than others. I don’t know that anyone has done any research on this, but there has to be a relevant multiplier for distance to park (e.g. if next door = 1, 100 miles away = .5? .3? – there’s any answer to this, but I don’t know what it is).

3. Some explanation/illustration of your claim that Hispanic populations are negative for baseball attendance needs to be given, as it is counterintuitive. Baseball is easily the most Hispanic major US sport (unless soccer is now a major US sport, which is plausible). The Hispanic population of the US tends not to be wealthy, but that’s captured in a separate variable here. That African Americans aren’t following baseball these days is well-documented. I find it impossible to believe that, controlling for wealth, Hispanic population is a negative for baseball at present.

1) I used MSAs exclusively. These delineations obviously aren’t perfect, but they’re also not arbitrary. They’re determined by commuting patterns, which (at least in theory) make them representative of how the local economy functions.

2) You’re absolutely right, but that aspect of it is a little tricky to quantify. But even without accounting for this, the other variables should still be revealing.

3) I agree this one feels counterintuitive, but that’s what the data say. The effect wasn’t very large, but it was statistically significant. Keep in mind that this variable doesn’t necessarily imply that Hispanics don’t follow baseball — Just that they don’t follow it as non-Hispanics.

In the Northern California case, the MSA/CMSA distinction is absolutely arbitrary. Or, to be more precise, it is a historical legacy of a point in the past when it wasn’t arbitrary, but it is arbitrary now, and has been since the late 1990s. Although I have my suspicions about a variety of places where I don’t live, I will refrain from making any further factual claim and switch back to the analytical principle that even one arbitrary variable effects a statistical analysis with a mere 30 data points: garbage in, garbage out.

Ideally, I would have liked to have included more cities for my analysis, but I didn’t have much choice. There are obviously only so many cities with MLB teams. The sample’s smaller that I’d like it to be, but at the same time, most of the findings I came away with make sense intuitively.

When accounting for population size, did you account for the different way in which Statistics Canada and the US OMB decides what is a CSA?

The reason I mention this is that there are several Quebec towns that are basically satellites of Montreal – St-Jean, Granby and Salaberry, to name three – that aren’t counted in Montreal’s CSA despite being within 50 miles of the city. St-Jean is just 31 miles from Montreal. Almost every large American CSA has towns as far/even farther than that – Easton, PA for NYC, Stockton for SF/Oakland/San Jose which are counted in the final numbers.

I think this is important because Montreal’s CSA is 3.8 million, but if you count the aforementioned towns, it goes up to over 4 million (which obviously strengthens any argument it should get a team).

Flynn, as you’ll see tomorrow, I did not try to directly apply my model to foreign cities — I felt the demographic data was just too different to be comparable. Instead, I applied the lessons from my analysis of US cities to international ones.

This article says a lot about MLB’s marketing efforts towards minorities, females, and the youth.

Looking forward to reading more!

1) Except at the very high and low ends, attendence on its own is a poor way to measure economic potential (even discounting TV revenue and luxury box sales) since it’s basically a measure of two things: 1) stadium capacity 2) team’s ability to correctly price their tickets’ face value to maximize revenue.

Because people pay very different prices for tickets in different places (Yankees’ tickets, for instance, start at ~$25 for bleachers and in the thousands for the “Legends Suite”), it’s not an apples-to-apples comparison. I’m sure, for instance, the Mets could sell out every game if they adopted the Orioles’ relatively generous ticket pricing scheme.

2) Something that seems true across several sports is that relatively-compact, older cities with traditional downtowns (Boston, Baltimore, Chicago, St. Louis, Pittsburgh) seem to “punch above their market-size” in attracting fans whereas sprawling sun-belt cities (Miami, Phoenix, Tampa, Atlanta, Charlotte, DFW, Houston) seem to have a lot of trouble relatively to the size of their population.

3) Without elaborating in any way, the next 6 teams should be:

Brooklyn

Indianapolis

Portland

Mexico City

Carolina (either RDCH or Charlotte)

Newark

Mexico City (or in the future Havana) would have the base to support a team. The experience of 2 MLB teams in Canada would say that putting a team outside the US is going to compete with one hand tied behind the back. There have been enough stories about American players (and wives) who have been spooked about living north of border, I suspect that teams south of the boarder would run into the same thing.

Spooked by Celsius and Kilometers

Spooked by a murder rate one-tenth of many U.S. cities

Spooked by a second official language

Spooked by tax-payer funded universal healthcare

Spooked by not being allowed to have guns

Spooked by living in the G7 nation highest on Michael Porter’s Social Progress Index

Yes, we’re a bunch of unarmed, granola-eating, communist, anarchist, polyglots. Thank you! But we love our baseball. Bring back the Expos and add the Vancouver Big Ones!

Yeah, I definitely think Carolina needs a team either in the Raleigh or Charlotte area. I just moved away after living there for 5 years and not having a baseball team within 6 hours was the worst.

Seems to me that, if DFW has problems (as a DFW resident, I’ve never seen the Ballpark at Arlington THAT un-full, even in the August heat), it’s because they chose to build an outdoor stadium halfway between the D and the FW. Put a dome in the middle of North Dallas and (to quote Carl Weathers) baby, you got a stew goin’.

Newark is an interesting option. The Devils of the NHL play in Newark and it seems to work for them. On the other hand the NBA Nets left Newark for Brooklyn and the local indie baseball team is bankrupt. People generally do not like to go to Newark; it has the same vibe as Detroit though Detroit may have a worse reputation now.

Alternatively they could build a baseball stadium in the Meadowlands near the football stadium. There is already plenty of parking there. Kansas City does something similar.

One more thing about baseball expansion in principle. It is well-documented that baseball is the most attendance driven of the major US sports – football’s money is overwhelmingly TV driven, basketball’s is also at a much higher rate than baseball’s. Baseball gets a lot of its steam from atmosphere (after all, people focus on the game itself less), making the night out at the ballpark with family or friends the selling point. Add to that the fact that baseball seeks a ticket buying base many times larger than other sports: 81 home games versus 8 for football, 41 for basketball; stadiums that seat 35K and up, smaller than football (but not by much) versus arenas that seat 15-20K. By definition this model requires the largest of metropolitan areas and exaggerates the effect that population size, transportation accessibility, and wealth of the fan base has on viability as compared to other sports.

All this adds up to the likelihood that – short of expanding to Mexico City, which would be interesting in many ways – major league baseball, unlike football and basketball, really has hit the limits of the possible in North America. By MSA size and wealth it is doubtful that any other place except Montreal, which is marginal, would be viable. And the other ones that might just barely make it, such as Indianapolis, Portland, Sacramento, and Brooklyn/New Jersey/fill-in locations in the densely packed northeast, would dramatically cut into fanbases other teams count on – ask the White Sox and Reds, the Mariners, the Giants and A’s, the Yankees and Mets, how they feel about these expansion possibilities.

The last time baseball contemplated changing the number of teams, it was contraction. I don’t think we’ll be seeing MLB expansion any time soon.

Love to see teams in Mexico City, Havana (some day) and Vancouver. Then it really would be a true North American sport.

An interesting study. Not sure how you can factor in Canadian cities (Toronto for MLB, Montreal & Vancouver as potentials) as stats recorded up here are a bit different than down there. Vancouver once was thought of as a strong possibility due to proximity to Seattle to create a rivalry. Don’t see it ever happening but there is a stadium there that can be adapted if needed quickly as they’ve played pre-season games there before last time in 1994 (it now has a retractable roof). Checking AAA I don’t see any million fan teams anymore (Buffalo & Indy used to do that). There was talk at one time of teams in Mexico but I don’t see it.

I wonder if the college-educated anti-correlation is caused by those people’s being fans of college football/basketball? Is there a way to split college-educated people into those who attended schools with Division I programs vs. ones without?

That could be part of it… Unfortunately, no. The Census only asks people if they went to college, not where.

Will a more technical write-up with the detail of your methodology and results be made available to those who are interested? As an economist with a dual specialty in sports economics and econometrics, I am interested in those details. Thank you.

Not sure that I’ll publish anything, but feel free to email me with any questions. I’d be happy to answer any questions or hear any criticisms. My email is mitchell.chris99 at gmail

so rich, white, and uneducated fans.. you just described Alberta.

MLB should get a bit more international. Apart from Vegas, Nashville and Portland, I don’t see a lot of obvious US expansion options.

Honolulu would obviously be fantastic and fit much of the listed criteria, but scheduling would be a huge concern. They’d probably need to arrange a special 6 game series per club visit.

I’d vote for Vancouver, Canada (to create a much needed PNW rival for the Mariners and to return another team to Canada), Mexico City/Monterrey, Mexico (many have argued that Monterrey makes more sense) or San Juan, Puerto Rico.

Man, Las Vegas would become the new Colorado in terms of places pitchers go to die. Oklahoma City would be interesting, maybe Portland, Louisville, Charlotte, New Orleans…

One wonders if the economics would work for Havana.

I think I have two:

Sacramento, CA

Pop’n ~ 1.5-million

Income ~ $55k

Poverty ~ 17%

White ~ 65%

College ~ 28%

Males ~ 49%

Temp. ~ It’s in CA

NBA (Kings), but no NFL

I could only find age for 65+ ~ 12%

San Antonio, TX

Pop’n ~ 1.4-million

Income ~ $46k

Poverty ~ 20%

White ~ 73%

College ~ 25%

Males ~ 49%

Temp. ~ It’s in TX

NBA (Spurs), but no NFL

I could only find age for 65+ ~ 10%

Probably could be San Jose instead of Sacremento, either way it looks like there is room for another central CA team (or for a current central CA team to move!)

And I guess I’ll add one more:

El Paso, TX

Pop’n ~ 0.8-million

Income ~ $40k

Poverty ~ 23%

White ~ 92%

College ~ 21%

Males ~ 49%

Temp. ~ It’s in TX

No NBA, no NFL

I could only find age for 65+ ~ 11%

Just re-read the part about race vs. ethnicity. While El Paso is 92% white, it is also ~81% Hispanic, so that would violate #2 above.

Nice research, except your reasoning concerning competing sports teams is flawed. Los Angeles, the second largest city in the country, is the ONLY MLB city without an NFL (or CFL in Toronto’s case) team unless you count Milwaukee and Green Bay or Dallas and Arlington as separate markets. You then considered NBA teams but left out the NHL, which skews the data in cities like St. Louis where the MLB team draws well with no competition from an NBA team yet still does so while competing with an NHL team in addition to their NFL team.

If you look at population/money New York is the most obvious place for an expansion team. Probably 2. Not going to happen, of course, because of the “territorial rights” thing but NY has several times the resources of anywhere left but only 2 teams.

The problem I see is that with 6 more teams some of these rosters are already full of AAAA players, then you throw in the injuries and to pitchers and now there back to 4 hour games

bluejaysstatsgeek, if only Canada could be moved about 2500 clicks south, it would be perfect.

The pool of players has not continued to grow. The number on American kids playing youth baseball has decreased significantly. African-American kids had simply stopped playing baseball for the most part. So where is this growth in the talent pool? Japan? One of the major reasons the number of Latin Americans in pro baseball is the significant decline on American kids playing baseball.

Weird. When the original post about expansion was released, it seemed to meet heavy resistance in the comments.

So what to do about that? Apparently you are supposed to continue on blindly.

Zimmerman’s initial premise is dumb. Why even bother expounding upon it?

If MLB is bound and determined to expand, Iowa and Hawaii would be great.

How about “fans in the stands” in lieu of ” butts in the seats?”

How about 32 teams, which could mean 4 leagues of 8 teams, with no “wild-card?” Then we could see 2 series of 7 games, followed by a 9 game World Series, just like it was “back in the day.”

And do away with the DH gimmick.

Michael Bacon’s suggestions are reasonable, especially considering the loathsome dh. But let’s be honest, the Tropicana Dome has little to do with Tampa’s poor attendance and much to do with the team’s constant whining that they have so far missed out on the ballparks-for-billionaires welfare program. Ripping off the taxpayers for a new playground hasn’t helped the Marlins much. The fact is that Florida is a poor market for MLB. Minor league teams, fine, Florida Instructional, fine, but the big guys just aren’t making it there. And the largest point of all–the big leagues are diluted too much as it is, good gravy, no more expansion! Although having said that, two more teams to make 32 wouldn’t make much difference and we can revise the ludicrous playoff system to ensure that really good teams are in, not just mediocrities in a weak division.

There are a lot of good comments and city suggestions. To piggyback on some aforementioned ones, I think OKC has some potential. While I don’t know what attendance is like for the AAA affiliate, I think that it’s difficult to reconcile whatever those figures might be and what could be expected for a MLB team. As a pro team just brings an elevated interest in general. So, even if those AAA numbers aren’t good, I still think it doesn’t inform too much; however, I think if they are good, then that does. It may seem like convenience to overlook the numbers should they not be good, but as I mentioned, it’s minor league, not pro, so if people are turning out already, it’s a good sign, but if they aren’t, that’s not necessarily indicative of what it would be like should a pro team come.

Further, we’ve seen how the city and state have taken to the Thunder. Yes, the early months, assuming the Thunder remain relevant and make the playoffs, would be difficult for the baseball team, but there is little to do or see during the summer months in Oklahoma. And while OU football and the like is huge and would be tough competition, the reality is that it’s only 1 day a week.

Also, it could be good, as natural rivalries would be present almost immediately. Most people in the the state are Rangers, Cardinals, or Royals fans, add in an Oklahoma team and that makes for some great potential rivalries for the region.

I can definitely see potential spread to Puerto Rico, Mexico, or even Cuba if the new detente holds, but that would be in the distant future. I can’t see Canada getting another shot in the foreseeable future, as attendance, and more importantly, tv ratings, simply don’t seem to be that great. Nashville and Indianapolis are interesting, as is Charlotte, or really anywhere in the South, as there is a lack of teams there (yes, I know football is king, but still).

Portland would be interesting just to see if that hipster-like fervor that gets the youth and old alike in the stadium to aggressively support a team would occur. Like with their soccer team, and like we see with the Seattle Seahawks sudden band-wagon and their soccer team as well.

Who knows. I know I don’t want the quality of the game to get diluted, or see any more terrible teams emerge. What that means for expansion I don’t know, but it’s crazy to think of the MLB getting further into the 30s when it comes to teams. Just seems like a lot.

Statistics can only support a potential expansion city. Statistics should NOT be used to negate a potential city. There are other important factors besides population size, education, income, and being white. I think the MOST important factor is having a multi-billionaire willing to support a team in a city that HE or SHE wants to play in. OWNERSHIP is far more important than any statistical factor. Second. Baseball culture is vital. If the home town does not have a baseball culture it will NOT succeed. Baseball towns can be created, but it takes time. Having a beautiful ballpark (a comfortable place to take your entire family) is VERY important in creating that culture. Local government support is a must. Baseball is fun, but it’s also shady behind the fun. Downright Mafia. Local government must be willing to bend the rules for a team to succeed. I have not read part 2 yet; but expansion cities I would consider….1.Monterrey,MEX; 2.SanAntonio/Austin,TX; 3.Carribean team (playing home games divided among three Gulf coast cities). Shutting down Guantanamo Bay Prison and turning it into a state of the art training facility and future MLB baseball park would be downright Mafia. 🙂 4.MexicoCity, MEX; 5.Omaha,NE; 6.Montreal,CAN. BEFORE any of this can happen, though, The Athletics and Rays need to “clean up”. I think the Marlins are cleaning up. And the new Commissioner may have to deal with the Brewers, too.