Ground Balls: A Hitter’s Best Friend?

Chris Davis knows the success one can have when you hit the ball in the air (via Keith Allison).

Hitting the ball on the ground creates something of a dichotomy for hitters and coaches. Some demand it, trying to put pressure on the defense by forcing more fielders to handle the ball on each play. A ball in the air can be caught for an out, but a ball on the ground requires a catch, a throw, and another catch to retire the batter. Others would like to hit everything in the air because there is only so much damage that can be done by a ground ball. With these conflicting beliefs, it may be difficult to understand what approach is truly best for all hitters, or each individual hitter.

Confusing things further, both of these camps often will talk about using the same swing to get opposite results. You can swing down to hit the ball on the ground, or you can swing down to produce backspin and hit it in the air. It seems irrefutably silly that both of these philosophies are alive and well in the baseball world, at all levels (including the highest levels, by my sources). Not only is this a paradox, but it is also the wrong kind of swing altogether. Swinging down greatly reduces the chances of squaring a ball up when the timing of the swing is not perfect, which is something we’ll look at later. First, let’s focus on balls after they have left the bat.

At the amateur level, fielders and field conditions are not as excellent as in the major leagues. Fewer ground balls are converted into outs due to reduced range, more errors, and bad hops. Additionally, power is a smaller part of the game in high school and college since players are not as physically developed. There are fewer players able to drive the ball consistently to the outfield and over the fence. Given this, it seems more reasonable to try to hit the ball on the ground at these levels. However, I would not advocate it for professional hitters, or those aspiring to be. The data I am presenting tell a different story.

Let’s start with some numbers. If a major league hitter wanted to gear his swing toward one type of batted ball, which one should he pick?

| Batted Balls Outcomes for 2013 MLB regular season |

|---|

| Batted Ball Type | OBP | SLG | OPS | ISO | wOBA |

| Grounders | .232 | .250 | .483 | .018 | .213 |

| Liners | .685 | .883 | 1.568 | .193 | .681 |

| Flies | .213 | .621 | .834 | .403 | .346 |

As most of us probably expected, line drives are the most desirable result. Fly balls have a large slugging percentage but the lowest likelihood of leading to a hitter reaching base. Ground balls own the lowest weighted on-base average of the three, and it’s not really close. Based on these simple stats, hitters should be trying to hit hard line drives to have the most success with a lean toward fly balls if they mis-hit a pitch. The 19 point advantage in on-base percentage does not make up for the 385 points in slugging percentage between ground balls and fly balls.

It should be noted that reaching on an error is much more likely on a ground ball than it is on a line drive or fly ball. Let’s assume that all reached on errors are from ground balls, and the full credit belongs to the hitter’s ability to get on base this way. The best reached-on-error rate last year was by Andrew McCutchen at 48 ROE/PA (reaches on error per plate appearance). If we crudely add that into the league average numbers, it equates to approximately 21 points in OBP, still nowhere near overcoming the enormous difference in production due to the extra-base potential of a fly ball. Again, this may play a bigger part in amateur baseball, but major league teams are pretty good at getting outs when you give them a ground ball.

This seems obvious from a majors-wide viewpoint, which is why so many pitchers try to force ground balls, and some get paid primarily for their ability to do just that. For another point in favor of hitting fly balls, I refer back to Tango and Lichtman’s analysis in The Book of groundball pitcher vs. flyball hitter matchups. Flyball hitters have a distinct advantage over groundball hitters against groundball pitchers. As more teams focus on stacking staffs with groundball pitchers, the importance of hitting the ball in the air becomes more important. To me, this has to do with swing path, which I will further explore later in this article.

Remember the numbers above are just for league average. What about for players who rely on their speed to produce offense? Perhaps they see a greater benefit to hitting the ball on the ground because they put more pressure on the infield defense to get the ball to first base. To explore this possibility, I looked at all of the qualifying hitters from the 2013 season and graded their speed using FanGraphs’ version of Bill James’ Speed Score. In the absence of reliable raw speed measurements, this gives a decent enough approximation of players’ absolute speed without too much added noise coming from baserunning intelligence.

Selection bias rears its head here, since players who are accruing enough plate appearances to qualify must be playing well enough to stay in the lineup. If the groundball approach is a viable strategy on any level, however, we should be able to find big-league regulars who succeed in this manner. We shouldn’t care as much about the approaches of players who can’t stick in a starting lineup. Here are the offensive numbers of these 140 hitters according to batted ball type:

| Batted ball outcomes for 2013 qualified hitters | ||

|---|---|---|

| Batted Ball Type | OBP | wOBA |

| Grounders | .239 | .220 |

| Liners | .694 | .695 |

| Flies | .231 | .378 |

We still see similar relationships to the league-average numbers above, with a slight uptick in production across the board. Now, see the relationship in this graph between speed and wOBA on ground balls:

Though not a perfect correlation, the expected advantage of fast hitters versus slow hitters on ground balls is present. How about just the fastest 25 hitters? How do they do on all batted ball types?

| Batted ball outcomes for 25 qualified hitters with highest Speed Scores | ||

|---|---|---|

| Batted Ball Type | OBP | wOBA |

| Liners | .689 | .701 |

| Grounders | .257 | .237 |

| Flies | .212 | .339 |

There is a much bigger difference in on-base percentage now between ground balls and fly balls, but the weighted on-base average rankings have not changed. Fast players still do better hitting the ball in the air than they do on the ground. Faster players also get a slight wOBA bump on line drives, likely by being able to take more doubles and triples than the average hitter.

Let’s look at the batted-ball data from another perspective. How about power-handicapped players? If a hitter has a low likelihood of hitting the ball out of the ballpark, perhaps he would be better served trying to keep the ball on the ground. Here are the same numbers for the 25 worst home run hitters in terms of homers per fly ball this past season. The rates of HR/FB range from 1.50 percent to 6.80 percent.

| Batted ball outcomes for 25 qualified hitters with lowest HR/FB ratio | ||

|---|---|---|

| Batted Ball Type | OBP | wOBA |

| Liners | .654 | .646 |

| Grounders | .248 | .229 |

| Flies | .162 | .235 |

Now we have some guys in the ballpark we were looking for. Looking at on-base percentage, there is a pretty wide gap, while in weighted on-base average it is virtually a coin-flip. Line-drive outcomes are not greatly affected by this group’s lack of power, still maintaining a .646 wOBA when the ball is hit square. Even more extreme, here are the same outcomes for the 10 worst power hitters:

| Batted ball outcomes for 10 hitters with lowest HR/FB ratio | ||

|---|---|---|

| Batted Ball Type | OBP | wOBA |

| Liners | .637 | .624 |

| Grounders | .248 | .228 |

| Flies | .146 | .201 |

Awesome! The best HR/FB rate in this group belongs to Alexei Ramirez, at 3.60 percent. As a group, they have a 27-point advantage for ground balls over fly balls. So, if a hitter expects to hit fewer than about four percent of his fly balls out of the park, he should probably give up and hit the ball on the ground, right? Not exactly.

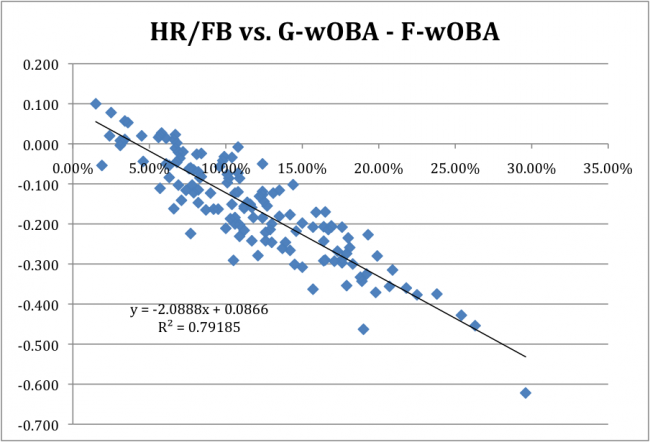

While grounders overtook fly balls in this table, line drives still have a huge production edge over the other two. If we added liners into the flyball numbers to show all balls hit in the air, there would be no comparison. These hitters still should be trying to hit the ball up, just not to hit it over the fence. Line drives are where it’s at, period. To show this relationship between power and wOBA difference, check out this graph of the full sample of hitters:

The better the home run-per-fly ball rate, the greater advantage in flyball wOBA over the groundball variety (obviously). You can see the small group above the x-axis where ground balls result in a higher wOBA that we already explored, all of whom had below-average HR/FB rates. The x-intercept of the linear regression line falls in at 4.15 percent, giving an estimate for the breakeven point in this sample.

You may have noticed the decreasing line drive wOBA in the last two tables as the power numbers have gone down. Most of this effect is likely because line drives hit by weak players are not as hard to defend as those hit by strong players. I also suspect that a hitter who sells out for ground balls will not hit line drives as often, or be able to achieve the same results from those line drives due to quality of contact. I attempted to find further statistical proof of this, but this is probably where the sample of hitters limits the analysis. Even the most groundball-heavy regulars must hit the ball well enough and often enough to warrant their consistent playing time.

Now for the swing itself. First, some logic, then we will look at a few examples of how hitters create these results.

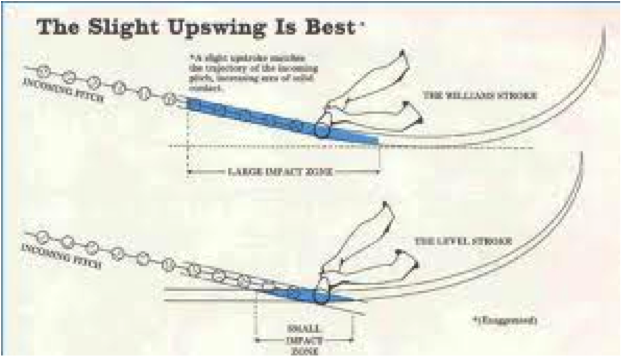

To consistently hit the ball flush, hitters need to swing on a slight upward path to match the ball on the same plane. Even line drives must be hit at a higher angle than level to the ground. Nothing really earth-shattering, since other research points to this already happening naturally.

Baseball Prospectus recently spotlighted a 2011 article by Matt Lentzner, in which he used PITCHf/x data to explore different aspects of pitch movement. He runs more numbers than I care to repeat here, showing a spectrum of pitches crossing the plate on a 4° decline for a shoulder-height Justin Verlander fastball down to 12° for a knee-high Adam Wainwright curveball. In an interesting graph from the piece, he showed the lowest whiff rate was present on pitches that crossed the plate on a 7° decline, suggesting the average major league hitter swings on something like a 7° incline. Ted Williams advocated this approach in his book The Science of Hitting many years ago:

This is the same reasoning that likely explains why flyball hitters do better against groundball pitchers than groundball hitters do. A groundball pitcher tends to throw pitches with more negative vertical movement. The correlation between pitcher groundball percentage and average vertical movement on fastballs (PITCHf/x data) is slight but appreciable (R-squared = .14). Flyball hitters tend to swing on a sharper uphill plane, matching the steeper downhill plane of groundball pitchers. This results in more true contact and driving through the ball on the same level, producing more hard line drives and well-hit fly balls.

So what does this look like? For a demonstration, let’s take a look at the leader in line-drive percentage among the 140 qualifying hitters from 2013, James Loney. Here he is hitting a double on a belt-high pitch into right-center field.

James Loney

The swing starts with Loney’s back elbow dropping under his hands and toward the pitcher. The hands drop in on top of the elbow before leveling off through the contact zone, until after extension when the hands roll over. Because the shoulders tilt slightly, the barrel is working underneath the hands by the time it starts to pass his back hip. This brings the swing path on a slight uphill plane, generating natural loft without relying on backspin to make the ball carry.

For further illustration, I would also like to show the hitters on opposite ends of the graph of groundball and flyball wOBA differences. Chris Davis had a flyball wOBA 622 points higher than that on his ground balls this past season. Marco Scutaro was the most extreme of the few with a higher groundball wOBA, coming in at 100 points higher than his flyball result. First, let’s see Davis crushing a home run to center field in Fenway Park:

Chris Davis

Here we see some moves similar to the swing above. The back elbow drops down below the hands, even more than Loney’s did. The hands work down on level with the elbow near the back hip before coming through the zone on an uphill plane. His shoulders are tilted toward the plate like Loney’s, perhaps more so, and his spine is much more angled back toward the catcher rather than relatively straight up. This positioning results in a very steep uppercut swing as he drives through the pitch. Even though some hitting coaches would refer to this as dropping the back shoulder, leading to too much length and uppercut, notice how tight the barrel stays to his body as his hands and elbow drop into plane. This keeps his swing short to the ball despite being in an uphill position with his upper body. Because he is so strong, he can gear virtually his entire body toward hitting the ball in the air and have tremendous success doing so.

For the other side of the spectrum, here is Marco Scutaro hitting a single into center field:

Marco Scutaro

The first move is similar to the previous two swings, though the hands and elbow go together more. The hands push in front of the elbow earlier than the other two, taking some whip out but likely lending more control to his swing. The hands come through level or on a slight upward plane, dropping under his shoulders before driving forward. His shoulders also tilt toward the plate, bringing the barrel of the bat underneath the hands. On approach to contact, the bat is swinging on a slight upward plane that matches the line of the pitch.

Even for a guy who should not be trying to hit a fly ball, he still swings up through the pitch, just not to the same degree as a guy like Chris Davis.

A quick note about the “swing down to create backspin and lift” sentiment: stop that. It is okay for guys to think in terms like this to keep from getting long with the swing, but please realize that this does not optimize batted-ball distance in reality. Swinging down on the ball while the ball is also going down will more often result in hitting the ball down or missing it, unless one possesses unbelievable hand-eye coordination.

While backspin does enable a ball to fly further, taking a path down to the ball is nearly impossible to do with any kind of consistency. In a sport where hitting .300 is lauded, I do not think this person exists. Even if a hitter could make contact that same way every swing, it sacrifices too much energy from the bat-ball collision in favor of more backspin. Physicist Alan Nathan has a great research article posted on his website detailing the math behind hitting a home run based on experimental measured ball flight. In it, he summarizes the results pertinent to this common teaching axiom:

For a typical fastball, the batter should undercut the ball by 2.65 cm and swing upward at an angle 0.1594 rad.

That value in radians converts to a 9.13° uppercut swing, representing the maximized swing path for energy transfer and backspin using a typical major league hitter’s bat speed.

I do not believe this is common practice or knowledge in major league baseball, which is unfortunate. I have heard a lot of second-hand horror stories about the philosophies of many organizations in the game. Especially at the big league level, there is little evidence that a true groundball swing will lead to success. Line drives are the key to hitting, regardless of hitter attributes. Speed appears to have less of an impact on a hitter than what popular belief says. While speed may help boost a player’s batting average on balls in play, fast hitters do not have an automatic incentive to hit the ball on the ground, based on these results. They can turn doubles into triples rather than just outs into singles.

That said, there is some (but little) wiggle room for individualized approaches to swing path. To tell Chris Davis and Marco Scutaro to have the same swing would be ridiculous. There are data here that show hitters who are not strong enough to hit home runs consistently may benefit from hitting more ground balls than fly balls. Again though, line drives are still best for even the least physical hitters. A slight uphill path to the ball should be the goal of every batter in order to maximize efficient contact and batted-ball success, with even more uppercut swings reserved for those who can drive the ball out of the park. Every hitter is different and has different strengths, but the wiggle room lies more in how high in the air each hitter should aim.

The bottom line: leave swinging down to bad hitters at the amateur level, who have no chance at playing at the highest levels of the game. Otherwise, hit the damn ball in the air.

Great article. One of the best I have read on hitting.

Thanks man, I appreciate it.

Great article and analysis! Ted Williams’ book doesn’t get the credit it should be due, particularly among saber sites, so I’m glad to see an article touting it. Every hitter should learn this from the day they enter little league.

You should google and read Andres Torres’ story of how he changed his batting mechanics to basically do what this article states hitters should do.

He was taught the standard “use your speed by hitting to the ground” technique of chopping at the ball that speedsters often get taught, but after years of no results, he felt his time was passing. So he decided to copy Albert Pujols swing, deducing that maybe he’s doing it wrong. So he searches for someone on the Internet to help coach him and he hooked up with someone who basically teaches Ted Williams book. He works on changing his batting mechanics and within a year, he’s incorporated it. Meanwhile, the Giants sign him, leading to his couple of good years in baseball (one really good one) plus a championship ring. Read the actual story, it’s even better with all the details.

I definitely don’t agree with everyone in Ted Williams’ book, especially since he didn’t actually do half the things he talks about (short stride, stay on the toes, etc.). I think just the idea of swing plane is enough to make it a good read.

I saw that story on Chris O’Leary’s site; pretty cool stuff. Pretty amazing how little most of pro baseball actually understands about player development. Too much politics in my opinion.

A thousand years ago we were taught to swing at the pitcher’s hand at the top of release, not unlike the idea of trying to hit the pitcher in the head with the batted ball. Try to get square on the ball and hit it to center. If you’re a little under it’s off the wall, a little over it’s a screaming one hopper, a little early or late it’s in a gap.

Very good piece, good to see some serious thought.

Your coaches must have been Venezuelan 🙂

American, but Ted Williams was still playing, Mickey Mantle had won a Triple Crown, and the men who taught me knew Tom Greenwade and Mickey Owens, among others. It was a good time to be a kid.

Great job Dan! Hope all is going well in LA. Very nice piece.

Thanks Jerry. I’ll email you sometime in the next week with some of the stuff I’ve been looking at.

Cool. Looking forward to it.

i like the topic of discussion, but i feel that the suggested uppercut for best results hurts a hitter more. i tend to be a follower of the backspin philosophy, and i think that your analysis should try to focus more on the point of contact and just prior to establish angle of bat. i would guess that the angle of bat at contact you suggest is slightly after contact and the natural upswing is in effect. all the great hitters that i look at ‘chop wood’ when hitting, i.e. downward swings (Albert Pujols). there may be more to what you mention about the downward path being mental and keeps hitters on the right approach more. im also on the fence when it comes to path of pitched ball, but have not put that much into this aspect. thank you for the article. Mike

While I admit Pujols has more of a flat bat path than some others, he is still more up than down in his swing path as it approaches the ball.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V89JddTPKB4

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fVZNFaFOQU4

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ye18rV5chnY

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tWuWqjvMmsU

The bat has to come down to get on plane with the ball, but it is not going down when making contact. Thanks for pointing him out though. He is certainly one that does flirt with the line.

False. Look at Pujols’ swing here. Power hitters don’t swing down on the ball.

http://www.chrisoleary.com/projects/Baseball/Hitting/RethinkingHitting/Essays/AlbertPujolsSwingAnalysis.html

In your link there was another link to something about bat speed: http://news-info.wustl.edu/news/page/normal/7535.html, with the claim that Pujols’s bat speed is “only 87 mph”. Unfortunately, while people are often fond of quoting bat speeds, they omit telling us where on the bat the speed is quoted. Generally speaking, the bat speed gets larger the closer one gets to the tip of the barrel, since the bat is (roughly) rotated about a point near the knob. However, as far as the baseball-bat collision is concerned, the only point that matters is the contact point. I seriously doubt that anyone consistently has a bat speed of 87 mph at the contact point under game conditions, since that would lead to batted ball speeds (assuming “perfect” contact) much larger than anyone has ever observed (from HITf/x, TrackMan, etc., these peak out at around 120 mph, which is quite a rare occurence).

Im not sure what pic of pujols you have been looking at but he does not chop wood. total rotates to ball good bat lag dropping barrel in path of ball very early good hitters bucket maintained then big bang occurs. look at video no chopping down on ball bat moving up on to contact.

Great article Dan! Obviously line drives are preferable. The question is where do we want to miss? The air or the ground? Hitting the ball in the air may give hitters a statistical advantage, but what about moving runners? What about the strategies of moving a runner to 3rd base with one out, or scoring a runner from 3rd on a ground ball with the infield playing back, or staying out of the double play by playing run-and-hit? These in-game advantages would not show up in these numbers, correct? Is hitting for average always the best approach to winning a baseball game in real time? Would like to hear your thoughts.

You can go through all the situations.

– Guy on 2nd, no outs: A flyball caught in RF or RCF probably gets the runner over, and one that falls in the gap scores him. Not enough of an offset to deviate from line-drive swing.

– Guy on 3rd, infield back: Medium-depth flyball or deeper scores him, plus the chance of extra bases. Not enough offset to deviate from line-drive swing.

– Hit-and-run: This is the closest I can see for your reasoning. However, a non-optimal barrel path means less chance of contact and more chance of hanging runner out to dry.

As you said, line drives are always best, and it would seem that taking a swing to give yourself the greatest chance to hit a line drive is the smartest thing to do.

For scoring the most runs, all “productive outs” are all net negative or break-even plays at best, according to run expectancy charts. Anytime the strategy is geared toward giving up an out for a base or a run, you are reducing the potential number of runs to be scored. For a hit-and-run, I remember seeing an article (can’t find the link) where a runner stealing on the pitch gained 20-30 points in batting average on the play, likely due to fielders moving and reduced range. Why give back that advantage by trying to hit a ground ball? Hit a line drive in the gap and have a chance to score the guy with less possibility of the batter getting out.

That said, just like with sac bunts, I can imagine win expectancy would tell a different story in some cases. In the last innings of a close game, there would definitely be situations where playing for one run is a reasonable strategy. However, this assumes that it’s inherently easier to hit a ground ball to the right side or a fly ball deep enough to score a runner that it is to hit a line drive. If guys are really that good at putting the ball where they want it, why should they settle for an out anyway?

Williams was certainly the better hitter on the field, but Charley Lau wrote the best book about hitting. “The Art of Hitting .300” is a masterpiece.

Definitely a more in-depth book. Some people have taken the one-hand v. two-hand extension thing way too literally though. It makes less sense when Charlie Lau even admitted he changed his thoughts about that late in his life.

Plus, I’m thoroughly convinced being good at hitting has zero effect on how good of a hitting coach somebody is. It helps to have worked through the process of facing good pitchers, tweaking the swing, and making other adjustments, but the fact is many of the greats succeed in spite of what their coaches have told them, not because of it. Most (not all) of the best hitters in the game think they swing down, squash the bug, keep the shoulders level, etc. The information they are exposed to in pro ball is often no better than the stuff you can find in homemade Youtube videos.

Flyball hitters probably strikeout a lot more. They may be hitting the ball harder/farther when they make contact, that’s if they make contact at all. I don’t think writers will be voting for Mark Reynolds/Carlos Pena over Derek Jeter/Ichiro Suzuki for HOF because they hit the ball farther.

Kind of cherry-picked examples…but nonetheless; selection bias makes it pretty tough to find a useful sample for your theory. It could just be that teams are willing to promote and keep a player in the big leagues despite his strikeouts BECAUSE he hits the ball in the air. Players who hit the ball on the ground and strike out a lot would not last long. For what (little) it’s worth, I ran simple correlations (R values) for K% to each of the batted ball types for the same 140 hitters:

FB% 0.39

GB% -0.33

LD% -0.13

Doesn’t really tell us much because of the sample issues, but the correlations are apparent yet weak. More fly balls correlate to more strikeouts among big league regulars.

This study validates Whitey Herzog’s advice to powerless but speedy Ozzie Smith to try to hit ground balls. I think he gave him a little bonus for each ground out and little fine for every fly ball (but presumably not for line drive hits).

One thing I’ve always wondered is if groundball hitters are more luck dependent than fly ball hitters from year to year. We know that ground balls and fly balls are converted into outs at a relatively predicatable rate, but I wonder if you take any particular year and examine the Out/GB rate per individual player versus the Out/Fly ball rate per individual player if you’d get a higher standard deviation for the GBs or the FBs and if that holds steady year over year or if it changes back and forth.

My hunch (though I freely admit it’s just a hunch) is that there would be more deviation for the GB hitters, thus making them more luck dependent from year to year. Which would be another point in favor of the value of hitting fly balls versus ground balls in that it would tend to produce a more consistent, reliable player on average.

and it just occurs to me that I forgot to lead with, “excellent, informative, well-written piece.” Thanks very much for the article.

I’m glad you enjoyed it. Thanks for the feedback!

Fly ball hitters sometimes have the tendency to have extremely low BABIP’s. That’s not a good thing at all. They’ll have longer slumps and lower batting averages because they can’t get lucky. Luck is good thing.

BABIP is the same as OBP in this study. Ground balls also have a low batting average in play, even in the speedy hitter group, and a much lower wOBA than on fly balls.

Good article. I’m a hitting instructor in Georgia and it seems like every instructor and coach in my area teaches the “A to C swing down for backspin” barrel path. One of my students is a senior in HS. He has the head coach telling him to swing down for backspin so the ball travels further, and the assistant coach telling him to swing down to hit ground balls, because he runs a 6.6 60 yard dash.

I’m a big proponent of Ted Williams’ ideas on hitting and use him as my model. His material is by far the best I’ve ever read. If all you do is read is book “The Science of Hitting”, you’ll never be able to piece together how he hit. In order to fully understand what he believed and what he did, you need to read or watch every interview you can find and read every first person account of people who talked hitting with him. If you do all that with an open mind, you’ll find that Ted was the Einstein of hitting.

Not only did Ted have an in depth knowledge of the physics involved in hitting a baseball, but he also had a very good understanding of bio-mechanics and how the human body naturally works.

Most of the commentary I’ve read by others regarding Ted’s ideas on hitting, doesn’t match what he said he did.

I’m convinced that happens everywhere; it does in Pennsylvania, Maryland and Southern California at least, by my knowledge. Even pro teams talk about the same thing.

As for Williams, I’ve heard a rumor that Joe Cronin wrote Ted’s book, with only minimal input from Ted himself. That would definitely corroborate what you say about revealing only a small part of his knowledge.

The amount of detail in Ted’s book leads me to believe he had a lot of input in writing it. Some of the question and answer sessions with Ted that I’ve come across over the years really helped to connect the dots from the book. Ted’s material on weight shift, balance and barrel path turned out to be the holy grail for me and helped me develop a simple system of teaching kids a high level baseball swing.

Unfortunately, most of the kids I work with have coaches that know more about hitting than Ted; and every other hall of fame MLB player. I’m 53 years old and had to swing a -1 or even weight wood bat from peewee on up. There was no such thing as -8 or -10 bats. The only way to hit decent with a wood bat is to use your body correctly. I never had a coach instruct me to do most of the stuff kids get taught today. Many of today’s coaches grew up in the light weight aluminum bat era, and have no clue how to teach kids how to sync up their bodies to hit with a -3 bat.

One thing left out: Bunting, which I assume is classed as a GB.

The small selection of really fast guys without power who do well would, I assume, include guys who occasionally bunt for a hit (as they are now trying to teach speedster Billy Hamilton). If they do it with some frequency they may pull the infield in enough to also improve their OBP on regular ground balls. Note there is no real bat path for a bunt, so they could easily use the correct upswing angle when swinging away.

Just checked into it; bunts are actually compiled in a separate category from ground balls. Good thoughts though.

Great article! When I have had discussions with college and high school coaches about this over the last 10 years, I ask them why do they want their pitchers to induce ground balls when on defense and yet want your hitters to hit ground balls while on offense?? Ask any pitching coach … a sign of a pitcher getting tired and in trouble is NOT when they are giving up ground balls, but instead when the ball is being hit in the air. BTW, not many double plays happen in the outfield. The greatest pitching coach of all time, Dave Duncan, said they constantly worked at teaching pitches to pitchers (movement, location) that induce as many ground balls as possible. So the philosophy of ground ball hitting CANNOT be good for both offense and defense.

I’m going to tell you exactly why Big league hitters do swing down. They have a slight downward path at the start of the swing not to hit ground balls it’s because they don’t want the barrel of the bat to flatten out to early. Believe me I played profesional baseball for 8 years.

You may have played but at contact the bat is on upward plain opposite the ball the barrel just drops in the path and the swing resembles a hula hoop tilted based on height of pitch. Barrel always below hand more vertical to ground than horizontal with high finish

great advise