Hall of Fame Plaques Reflect the Style at the Time

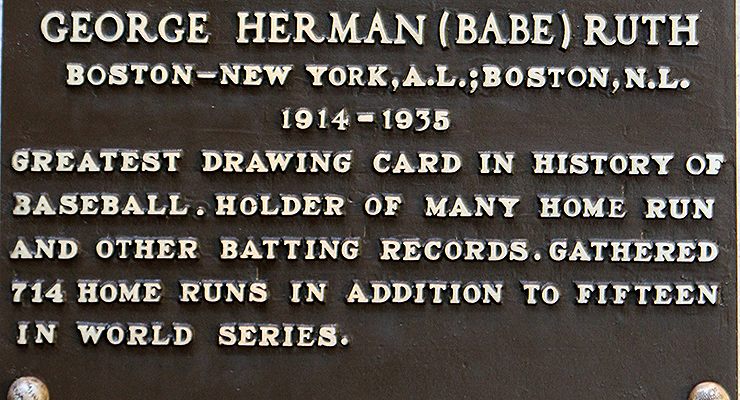

Babe Ruth’s Hall of Fame plaque is nothing if not concise. (via Dan Gaken)

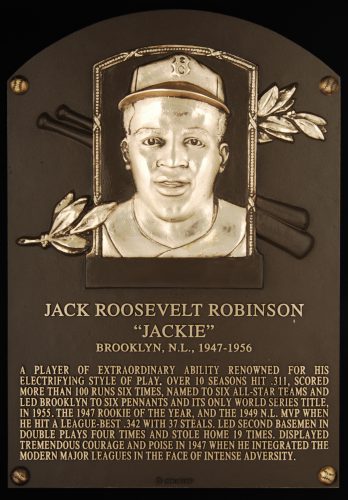

Wade Boggs’ is the first to mention on-base percentage. Lou Boudreau’s describes him as a “player-pilot,” a term that’s been out of use for more than half a century. Jackie Robinson’s initially made no mention of him breaking the color barrier. Phil Rizzuto’s reads almost like a defense for inclusion, noting he had a “solid .273 batting average” and (this seems like an odd thing to highlight) “peaked with a .439 slugging percentage” one season. The first line of Babe Ruth’s is “Greatest drawing card in history of baseball.”

We’re talking, of course, about Hall of Fame plaques, which are ripe with charming, informative and idiosyncratic text, often reflective of the era in which they were written.

Ruth? He “gathered 714 home runs.” Jack Beckley? He “made 2930 hits.” Cool Papa Bell? “Hit over .300 regularly, topping .400 on occasion.” Love that – “on occasion,” as if it were the decision to wear a tuxedo.

Ruth? He “gathered 714 home runs.” Jack Beckley? He “made 2930 hits.” Cool Papa Bell? “Hit over .300 regularly, topping .400 on occasion.” Love that – “on occasion,” as if it were the decision to wear a tuxedo.

“The plaques illustrate the way that we, the baseball fans and the baseball industry, have changed our mindset and the way we talk about the game,” said Jon Shestakofsky, vice president of communications and education for the National Baseball Hall of Fame. “Not only have things changed grammatically and linguistically over time, which was pretty funny to see. But also the types of information that are going up on plaques, like a lot more stats.”

The writing of the text on the 314 plaques now hanging in Cooperstown has always been a collaborative effort between Hall historians and the communications department, traditionally with no input from inductees.

“The way we think about it is, if we ever tried to run it by players, it would never get done,” said Shestakofsky, laughing.

Exploring the gallery of plaques is like leafing through old copies of The Sporting News, where many of the terms and descriptions seem quaintly dated – even instructional. Do you know what constitutes a perfect game? If not, you can read the last line of Cy Young’s plaque: “Pitched perfect game May 5, 1904, no opposing batsman reaching first base.”

The first five members of the Hall of Fame – Ruth, Ty Cobb, Honus Wagner, Christy Mathewson and Walter Johnson – were elected in 1936. Their plaques topped out at around 30 words. If someone asked you to summarize the career of Babe Ruth in so few words, how would you do it? With stats? A description of his stature in the game? A mixture of both? Ruth’s full plaque actually reads:

Greatest drawing card in history of baseball. Holder of many home run and other batting records. Gathered 714 home runs in addition to fifteen in World Series.”

That’s it, 27 words over three lines — for the greatest player in baseball history. With the help of laser printing and a more concise font, more recent plaques can have around 90 words. If you were charged with writing (or re-writing) Ruth’s plaque, maybe you would mention his pitching excellence, too. Or that he long held the record for consecutive scoreless innings in the World Series. Nevertheless, the plaques were never meant to be exhaustive descriptions of a baseball figure’s career, any more than a tombstone contains the full impact of a person’s life.

“You look at Babe Ruth’s plaque, there’s a short snippet and it doesn’t really have numbers on it,” Shestakofsky said. “It more describes his impact on the game. And then you look at a guy who went in a few years ago, let’s say Pedro Martinez. It’s much heavier on text, many more words and lines. By comparison that might look like a big difference, but you’re still talking about 85 to 90 words to sum up an inductee’s entire career and impact on baseball. It’s not an easy task by any means. We try to emphasize the Hall of Famer’s unique place in the game and their stamp on history and hopefully offer something distinctive that stands out a little bit.”

“You look at Babe Ruth’s plaque, there’s a short snippet and it doesn’t really have numbers on it,” Shestakofsky said. “It more describes his impact on the game. And then you look at a guy who went in a few years ago, let’s say Pedro Martinez. It’s much heavier on text, many more words and lines. By comparison that might look like a big difference, but you’re still talking about 85 to 90 words to sum up an inductee’s entire career and impact on baseball. It’s not an easy task by any means. We try to emphasize the Hall of Famer’s unique place in the game and their stamp on history and hopefully offer something distinctive that stands out a little bit.”

In addition to the relative paucity of stats on Ruth’s plaque, it reads, “Gathered 714 home runs.” No one today would say that a hitter “gathered” home runs or hits. But such era-respective terms pop up regularly on plaques throughout the years.

Walter Johnson’s plaque begins, “Conceded to be fastest ball pitcher in history of game.” Ball pitcher? Were there other types of pitchers in those days? Of course not, but that’s how they were widely described.

It’s written of Connie Mack, who was inducted in 1937: “Received the Bok Award in Philadelphia in 1929.” What’s the Bok Award? Got me, but it was apparently a big enough thing in its day to merit mention on his Hall of Fame plaque.

It’s written of Connie Mack, who was inducted in 1937: “Received the Bok Award in Philadelphia in 1929.” What’s the Bok Award? Got me, but it was apparently a big enough thing in its day to merit mention on his Hall of Fame plaque.

(Note: Okay, I looked it up. The Bok Award is more commonly known as The Philadelphia Award and is given annually to a figure in that city whose “service to others tends to make lives happy and communities prosperous.” Also, Connie Mack’s name before he shortened it was Cornelius McGillicuddy. Not surprisingly, his full name does not appear on his plaque.)

In 1938, Grover Cleveland Alexander was elected as a member of the Hall’s third class of inductees. His might have the best text of any plaque, the last line reading, “Won 1926 World Championship for Cardinals by striking out Lazzeri with bases full in final crisis at Yankee Stadium.” Beyond the type of flowery language that might have made Grantland Rice proud, it’s notable that Tony Lazzeri was on a Hall plaque by last name only in 1938 — 53 years before he himself was inducted in 1991.

Part of Lou Gehrig’s 1939 plaque reads, “Holder of more than a score of major and American league records,” back when everyday people knew the score, i.e., that the word meant 20.

“I think about it the same I do in seeing old baseball headlines in the pre-World War II era,” Shestakofsky said. “It was just a different world and a different way of writing and consuming the drama of the game. I really enjoy reading those older plaques and kind of reveling in the alternate language. It’s a lot of fun and it really just reflects a different way of connecting with the game.”

Slugging percentage is routinely mentioned on plaques throughout the years, while statistics such as on-base percentage (which weren’t duly appreciated for many years) are notably absent. Ted Williams has the highest on-base percentage in history (.482), but his 1966 plaque doesn’t mention it. In fact, the first plaque to cite on-base percentage was Wade Boggs’ in 2005.

Among the most charming aspects of Hall of Fame plaques are the inclusion of tidbits that might seem extraneous (or even insulting) given the dearth of available space. The first line of Ernie Lombardi’s is a back-handed compliment: “Hit .306 over 17 seasons despite slowness afoot.” The last line of Travis Jackson’s plaque reads, “Drove in more than 90 runs three times, reaching 101 on .268 average in 1934.” I’m not sure Jackson (a .291 career hitter elected in 1982) would have elected for the last stat on his Hall of Fame plaque to note a .268 batting average.

Among the most charming aspects of Hall of Fame plaques are the inclusion of tidbits that might seem extraneous (or even insulting) given the dearth of available space. The first line of Ernie Lombardi’s is a back-handed compliment: “Hit .306 over 17 seasons despite slowness afoot.” The last line of Travis Jackson’s plaque reads, “Drove in more than 90 runs three times, reaching 101 on .268 average in 1934.” I’m not sure Jackson (a .291 career hitter elected in 1982) would have elected for the last stat on his Hall of Fame plaque to note a .268 batting average.

It’s not just words but also punctuation that has changed. For Frank Robinson, the text partly reads, “Set records for hitting homers in 32 different parks and with pair of grand-slammers in successive innings in 1970.” Not only is the term “grand slammers” no longer in common use, but “grand slam” is no longer hyphenated. But many words that are now written as two separate words were commonly hyphenated. “Home-run” is hyphenated in describing the accomplishments on Home Run Baker’s plaque (though, strangely, his nickname is not), and “Grand-slam” is hyphenated on Ernie Banks’ plaque, whereas no one would hyphenate either of those words today.

Banks, for his part, is recognized for once leading the league in slugging percentage, which might seem like a trifle to mention when you only have so many words with which to highlight a Hall of Fame career. Meanwhile, Barry Larkin’s plaque makes no mention of him winning the 1995 National League MVP, even though at the time he was the first NL shortstop to nab that honor in more than 30 years.

Banks, for his part, is recognized for once leading the league in slugging percentage, which might seem like a trifle to mention when you only have so many words with which to highlight a Hall of Fame career. Meanwhile, Barry Larkin’s plaque makes no mention of him winning the 1995 National League MVP, even though at the time he was the first NL shortstop to nab that honor in more than 30 years.

Many plaques mention a player’s nickname, including “The Say Hey Kid” for Willie Mays and “Country” for Enos Slaughter. Some seem superfluous, i.e., “Mike” for Michael Joseph Piazza — particularly when you see that Michael Jack Schmidt didn’t receive the same treatment. Meanwhile, Raymond Brown’s plaque notes that his nickname was, wait for it, Ray; Anthony Gwynn was “Tony”; and Thomas Michael Glavine’s was “Tom.”

Some of the nicknames were new on me, including “Beauty” for Dave Bancroft. By the way, with all due respect to Tim Raines, there’s already a “Rock” in Cooperstown. That was Earl Averill’s nickname, and it says so on his plaque.

It’s educational to learn that Roberto Alomar’s real last name is Velasquez. Bert Blyleven’s plaque lists his full birth name: Rik Aalbert Blyleven. Oddly, the plaque for former Negro League owner Effa Manley, who was inducted in 2006, does not mention that she was the first woman elected to the Hall of Fame.

Several plaques have been amended over the years to account for corrections to stats and dates played. Jackie Robinson’s text was given a wholesale rewriting; initially when he was elected in 1962, he didn’t want the focus to be on him breaking the color barrier, so the text cited only his on-field play. It was later changed and now ends with the line, “Displayed tremendous courage and poise in 1947 when he integrated the modern major leagues in the face of intense adversity.”

Several plaques have been amended over the years to account for corrections to stats and dates played. Jackie Robinson’s text was given a wholesale rewriting; initially when he was elected in 1962, he didn’t want the focus to be on him breaking the color barrier, so the text cited only his on-field play. It was later changed and now ends with the line, “Displayed tremendous courage and poise in 1947 when he integrated the modern major leagues in the face of intense adversity.”

“Clearly over time, it was decided that based on his place in history, outside of what happened on the playing field, it deserved to be mentioned, so that plaque was updated to reflect his unique place in the game,” Shestakofsky said.

That doesn’t overstate things in the least. The same cannot be said about other Hall of Fame plaques, where hyperbole runs rampant. Rickey Henderson’s opens with “Faster than a speeding bullet.” George Brett’s reads in part, “A clutch hitter whose profound respect for the game led to universal reverence.”

(Why am I picturing him tearing out of the dugout in the Pine Tar Game?)

The purple prose that marked Grover Cleveland Alexander’s plaque has not disappeared from plaques over the years. Glavine’s opens with “Durable, dominant and deceptive starting pitcher,” and Greg Maddux’s with “One of the game’s most consistent, composed and celebrated starting pitchers.”

The text of plaques continues to evolve, but an appreciation for the written word continues to shine through in honoring the national pastime and the players and figures central to its history. Inductees don’t see what’s written on their plaques until the monuments are unveiled during induction ceremonies.

“I think the players enjoy seeing for the first time what’s on their plaques,” Shestakofsky said.. “They get a real thrill out of it.”

I’ve never been to the Hall-of-Fame. I don’t find an image of Bob Uecker’s HOF plaque on-line.

Do Ford Frick inductees get a plaque like “regular HOFs” (insert your own Uecker humorous delusion here)?

If he has a plaque is it on display in the parking lot “just a bit outside?”

Is the famous hepatitis syringe used on him to help the ’64 Cards on exhibit? Help me out please.

“It’s educational to learn that Roberto Alomar’s real last name is Velasquez.”

That’s his mother’s maiden name.

To explain this a bit more, here’s the relevant explanation of Spanish naming customs from Wikipedia:

“According to these customs, a person’s name consists of a given name (simple or composite) followed by two family names (surnames). The first surname is usually the father’s first surname, and the second the mother’s first surname. In recent years, the order of the surnames can be reversed at birth if it is so decided by the parents. Often, the practice is to use one given name and the first surname only, with the full name being used in legal, formal, and documentary matters, or for disambiguation when the first surname is very common….”

So “Alomar” is his real last name. Also, “Alomar Velasquez” is his real last name. Also, “(Velasquez) Alomar” is his last name. It depends on context.

Keep in mind this is the custom. Not everyone follows it.

For further example, Juan Marichal’s plaque reads “Juan Antonio Marichal Sanchez” and Orlando Cepeda’s says “Orlando Manuel Cepeda Pennes.”

Roberto Clemente’s plaque reads Roberto Clemente Walker, also using both surnames. However, the original plaque in 1973 read Roberto Walker Clemente. It was recast in 2000, to correct for the common usage of the father’s surname first.

This is correct.

This is the standard Spanish naming convention and should be recognized as such. With so many players from Latin America in baseball understanding this part of their culture should be second nature to most baseball fans by now.

Through my reading of WW II history, I have learned that the correct use of Japanese names is family name last and given name first. Thus, the person generally referred to in most American histories as Isoroku Yamamoto (the admiral who planned the attack on Pearl Harbor) should actually be Yamamoto Isoroku. I assume that Ichiro Suzuki, therefore, should actually be Suzuki Ichiro, unless the custom has changed.

When speaking or writing in Japanese, the family name comes first, the given name second. When speaking or writing in a Western language that usually does things the other way around (like English), however, the names are reversed to conform to the standards of that language. This is a widely-held custom that goes back to the 19th century. So if you were speaking in Japanese, you would say Ichiro’s full name “Suzuki Ichiro”. But if you are writing or speaking in English, “Ichiro Suzuki” is appropriate.

In Chinese and Korean, the family name also comes first, the given name second. Unlike Japanese, however, these languages never developed a custom of reversing the names when speaking or writing in a Western language. So if you are speaking or writing in a Western language and you refer to a person who is from China or Korea, you would give their name family name first, as it would be in Chinese or Korean. For example, the Chinese dictator Mao Zedong’s family name was “Mao” and his given name was “Zedong”, but he is called “Mao Zedong” in both Chinese and English. It would not be appropriate to call him “Zedong Mao” in English.

This becomes trickier when you are talking about people of Chinese or Korean ethnicity whose families have permanently immigrated to countries where Western languages are predominant, or who even just live in areas or belong to subcultures with a significant Western (typically English) linguistic influence. Without getting too deep into the weeds, it would be fair to say that many such people who permanently reside in Western countries have adopted Western name order, and that anyone who has a Western given name or who goes by a Western nickname (either exclusively, or in addition to a traditional Chinese or Korean given name) is going to follow Western name order when speaking or writing in a Western language.

Great read. But it should be Jake Beckley not Jack Beckett earlier in the article

Fixed. Thanks for the catch!

Use of the word “gathering” when referring to numbers was common years ago. I remember reading The Sporting News in the ’60’s and seeing it used often. I do not have the time to sift through all the old editions I have but did a Google search and came up with this “6/24/1960: The Cubs were at Forbes Field in Pittsburgh to play the Pirates. They lost their eighth consecutive game by a score of 4-1 as the Pirates gathered ten hits, all singles, to score their runs.”

And here is a quote from “Had Em All The Way” about the 1960 Pirates: “Early in the season he gathered clutch RBI in bunches.”(page 205)

Baseball is no different from the larger culture. Words change meaning. We all could probably think of many phrases that were buried years ago and not resurrected. My favorite that I never see anymore is “belting” a home run. The word originated from a form of corporate punishment that most boys of a bygone era experienced regularly: their fathers disciplining them with a belt. Thus “belting” a home run.

Fun article!

The early plaques portrayed the players as heroic, like their sorbiquets (nicknames) like “The Grey Eagle” for Tris Speaker; “The Iron Horse” for Lou Gehrig; “The Sultan of Swat,” for Babe Ruth, etc. These basically died out by the 1950s, and were finished off by the In Your Face journalism of the 1960s. Today’s plaques reflect mainly stats and awards- you can’t argue with them.

Imvu credits are the credits which works as money at the IMVU and this link http://freeimvucreditshacker.com has a tool which generates imvu credits online.

This Royal version has the same color scheme and color blocking as the OG Royal 1, which means that a Black and Blue upper is placed top of a White midsole and Royal outsole.