Leverage Matters: When to Invest in the Bullpen

Koji Uehara’s value will differ depending on the team that signs him (via Keith Allison).

Who was the best pitcher in the American League in 2013?

By WAR, it was Max Scherzer, although teammate Anibal Sanchez had a better ERA, and Yu Darvish had more strikeouts. King Felix and Chris Sale also had excellent seasons and could be considered. One name you might not expect to hear is Greg Holland, although by one measure, he helped his team win games more than any other pitcher in the Junior Circuit.

Baseball statistics exist on a spectrum from predictive to descriptive. Pitching metrics like SIERA and xFIP try to predict future outcomes based on exhibited skills. Moving down the spectrum, FIP and ERA describe what happened, in terms of the pitcher’s K/BB/HR or total runs allowed. Near the end of the spectrum is a statistic that best describes how a player influenced his team’s chances of winning each time he played: Win Probability Added (WPA).

It is by this metric that Greg Holland led the AL in 2013.

Let’s be clear: I’m not saying that Holland is better than or even close to being as valuable as Scherzer, Darvish and Sale. This just illustrates that his contribution to his team’s record was greater than any other pitcher’s. In fact, if you look at the pitching leader boards and sort by WPA, relievers routinely place very highly on the list, including seven of the top 10 in 2013.

This is one of many arguments used when people claim that WAR systematically undervalues relief pitchers. To some degree, this is a valid point. Having an elite reliever to pitch in high-leverage situations can be have just as much of an impact on a team’s performance as having a dominant starter. Plus, since leverage is largely determined by the manager, it actually has a higher year-to-year correlation than performance metrics like FIP and xFIP, making it both predictable and repeatable. However, if a team has a second similarly skilled reliever who could have taken care of those high-leverage innings with similar proficiency, then the first pitcher doesn’t seem quite as valuable.

Regardless of how you evaluate players, we can all agree on two things. First, determining the value of a relief pitcher or an entire bullpen is extremely difficult, perhaps more so than any other position on the field other than catcher. Second, a great relief pitcher and smart bullpen management can provide a tremendous value to a team over the course of a season.

What this means is that a team that has a better understanding of how bullpens work can make smart investments in relievers without paying a premium for pitchers who won’t throw meaningful innings. Also, if there are certain team characteristics that correlate with an increase in high-leverage situations for relievers, a team can decide the best time to make a big investment in the bullpen.

With that in mind, let’s take a closer look at how relief pitchers are valued by different metrics, the importance of leverage in constructing a bullpen, and characteristics of teams where the bullpen performance may be of increased importance.

Chaining: A Primer

As mentioned above, relievers can have a disproportionate impact on their team’s performance relative to their workload by pitching in higher leverage situations. For starting pitchers, WAR effectively incorporates the pitcher’s performance (park- and league-adjusted FIP) and volume (innings pitched). This method fails to capture the increased importance of late-inning relievers, which is where chaining comes in.

With chaining comes the concession that leverage should be included in some capacity for reliever WAR, but with the caveat that a relief pitcher shouldn’t get full credit for the leverage of the situation he pitches. Why? Well, if a team’s closer or “relief ace” who pitched in the highest leverage innings were to leave the team or get hurt, it’s not like those innings would disappear. They would simply get occupied by the next-best reliever. After that, everyone in the bullpen effectively moves up the chain, and the pitcher who is actually replacing the closer will end up pitching mostly low-leverage innings.

(For a more detailed explanation of chaining, read Dave Cameron’s discussion of WAR and Relievers, or this piece by Sky Kalkman at Beyond the Box Score.)

As it stands now, reliever WAR essentially gives the pitcher credit for half of the additional leverage that he pitches in above average situations (LI + 1 / 2). This is very important to remember when referencing reliever WAR. Two pitchers who have the same adjusted FIP and workload can end up with different WAR values because of their usage. To illustrate this point, let’s take a look at a few relief pitchers in 2014:

| Relief Pitcher Comparison, 2014 (through Aug. 5) |

|---|

| Name | Team | IP | FIP- | pLI | (LI+1)/2 | WAR |

| Andrew Miller | — | 44.0 | 44 | 1.43 | 1.22 | 1.5 |

| Zach Duke | Brewers | 44.1 | 57 | 1.09 | 1.05 | 0.9 |

| Steve Cishek | Marlins | 47.2 | 57 | 2.11 | 1.56 | 1.5 |

| Jonathan Papelbon | Phillies | 46.1 | 69 | 2.20 | 1.60 | 1.2 |

These relievers all had pitched between 44 and 48 innings as of Aug. 5. We see that Miller had been the best of the group judging by FIP-, and while he had been 13 percent better than Cishek over a similar workload, their WAR is identical at 1.5, because Cishek had pitched in more high-leverage situations than all but four other relievers in baseball.

Similarly, Duke had put up an excellent season in the Brewers’ bullpen, but given his track record of mediocrity, hadn’t thrown in many high-leverage situations. Therefore, his WAR sat at just 0.9, despite the fact that he performed similarly to Cishek. Even Papelbon beat Duke’s WAR, as his high-leverage usage more than made up for the gap in performance.

Generally, the better a pitcher performs, the more trust he gains from his manager, and the higher leverage innings he will pitch. This means that there’s usually a decent correlation between performance and leverage, but there are always outliers (like Duke).

Leverage by Bullpen Slot

To get a picture of an “average bullpen,” I pulled all relievers from 2004-2013 who threw at least 40 innings in a season and sorted them by average leverage index (pLI). The results show what the back end of a typical major-league bullpen has looked like over the past decade:

| Bullpen Usage by Slot, 2004-2013 |

|---|

| Slot | SV | IP | ERA- | FIP- | pLI | WPA | WAR |

| RP1 | 28 | 65 | 70 | 79 | 1.87 | 1.59 | 1.2 |

| RP2 | 7 | 65 | 78 | 85 | 1.44 | 0.82 | 0.8 |

| RP3 | 2 | 62 | 82 | 90 | 1.18 | 0.52 | 0.6 |

| RP4 | 1 | 59 | 89 | 94 | 0.97 | 0.09 | 0.3 |

| RP5 | 0 | 57 | 94 | 100 | 0.77 | -0.06 | 0.2 |

| RP6 | 0 | 55 | 103 | 105 | 0.52 | -0.16 | 0.0 |

While managers tend to catch a lot of flak for improper bullpen use, we see that across baseball, the pitchers who are throwing the most important innings are also those with the best numbers. These also happen to be the pitchers who are racking up the most saves, as save opportunities tend to have fairly high leverage. (Of course, this isn’t to say that there aren’t a number of teams and managers who could do a much better job of using their relievers.)

It is well known that relief pitchers generally allow fewer runs than their FIP would predict. The fact that every average bullpen slot is capable of doing this tells us that it has more to do with the nature of the bullpen than the skill of the pitchers. However, there is a bigger gap between ERA and FIP for the good relievers (slots 1-3, ERA- is 8 percent better on average) than those who are closer to replacement level, so perhaps some credit is due.

Another striking trend in this chart is how quickly the reliever leverage decreases. In an average bullpen, only one or two pitchers are regularly throwing “high leverage” (LI > 1.5) innings, and only three are throwing innings with above-average leverage.

What does this mean? In simple terms, it probably makes sense for a team to invest in two or three quality relievers who are capable of shouldering these innings. Beyond those first few bullpen slots, leverage has little impact on how relievers contribute to their team.

Put another way, the scarcity of high-leverage situations means that a team will receive diminishing returns from investing in relief pitchers.

Modeling Leverage, Performance and WPA

Using our “typical bullpens” from the past decade, we can try to model the relationship among leverage, performance and WPA from relievers. For each bullpen slot, we can run a linear regression to find how performance (measured by ERA-) influences team impact (WPA). This gives us the following chart:

If a team is investing in a “relief ace” (RP1), an improvement by 10 points of ERA- will yield an average of +0.6 WPA. If a team already has an established closer and is looking for a setup man (RP2), that same 10-point improvement will project to help the team by only +0.4 WPA. This may not seem like much, but with the cost of a win hovering around $7 million, this difference can be measured in the millions of dollars.

Obviously, the extreme left side of this graph is where relievers can be highly valuable. Only a few pitchers each year post an ERA- below 40, but if used correctly they can have a huge influence on a team’s performance.

In 2008, Brad Ziegler posted an ERA- of 25 in 59.2 innings for the Athletics. While his average leverage was only 1.69 (a bit below the RP1 average of 1.87), he was still able to contribute +3.20 WPA for his team, despite having a WAR of just 0.6. Meanwhile, after six consecutive seasons with an ERA of 4.50 or worse, Dennys Reyes had a miraculous 0.89 ERA (20 ERA-) for the Twins in 2006. However, since the team presumably didn’t feel he could keep posting incredible numbers (rightfully so), it kept him out of high-leverage situations (LI of 0.88, in RP4/5 territory) and he accumulated only +1.45 WPA.

Let’s use the model above to analyze some hypothetical examples, to illustrate how chaining works and why investing in a bullpen provides diminishing returns.

Example 1: Diminishing Returns

The 2014 season has ended and free agency has begun. Several elite relief pitchersare on the market, including Koji Uehara, who has a career ERA- of 52, and is willing to settle on a one-year contract given his advanced age (for a professional baseball player, that is). Two teams have emerged as frontrunners for him: the Kansas City Royals and the Texas Rangers. Uehara projects for 2 WAR on the season, which should be worth around $15 million on the open market.

To determine exactly how Uehara would help these teams win, they look at how their bullpens would look if they sign him.

| Koji Uehara Comparison |

|---|

| Rangers | Rangers + Uehara | Royals | Royals + Uehara | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RP# | ERA- | WPA | ERA- | WPA | ERA- | WPA | ERA- | WPA |

| RP1 | 78 | 1.15 | 52 | 2.62 | 55 | 2.45 | 52 | 2.62 |

| RP2 | 95 | 0.12 | 78 | 0.82 | 60 | 1.57 | 55 | 1.78 |

| RP3 | 95 | 0.10 | 95 | 0.10 | 65 | 1.05 | 60 | 1.21 |

| RP4 | 100 | -0.13 | 95 | -0.02 | 95 | -0.02 | 65 | 0.61 |

| RP5 | 100 | -0.14 | 100 | -0.14 | 95 | -0.05 | 95 | -0.05 |

| RP6 | 105 | -0.18 | 100 | -0.14 | 100 | -0.14 | 95 | -0.11 |

| Total | – | 0.91 | – | 3.24 | – | 4.86 | – | 6.06 |

The Rangers don’t have much of a bullpen this year. The only reliever who has at least 0.3 WAR and is under team control next year is Nick Martinez, who has spent most of his season pitching out of the rotation. Therefore, I filled their hypothetical 2015 bullpen with mostly mop-up guys who are roughly league-average or worse. Because the Rangers don’t have another capable reliever to take on high-leverage innings, Uehara’s presence at the back of the bullpen becomes extremely valuable, worth an increase of 2.33 WPA.

The Royals, on the other hand, have had one of the most dominant bullpens in 2014, and return most of the key pieces. Their top three relievers this year — Greg Holland, Wade Davis and Kelvin Herrera — are all under team control in 2015. Because of the Royals’ bullpen depth, adding Uehara would mean that Herrera (RP3, 65 ERA-) would be bumped down to the RP4 slot, where his leverage will be roughly average despite posting RP1-type numbers. As such, the result is a WPA increase of just 1.20.

So, an elite reliever like Koji Uehara is worth significantly more to a bad bullpen than a good bullpen. The more quality relievers you have, the more likely you are to end up with a good pitcher throwing innings that aren’t very meaningful. If these two teams were bidding on a reliever in free agency, they might be willing to pay very different sums of money, even if they are on the same budget and have the same evaluation of the player in question.

Example 2: The Elite Setup Man

In February, I wrote about how teams may benefit in the long-term by preventing pre-arbitration relief pitchers from accumulating saves. The arbitration process places way too much value on saves, so young relievers who close out games become very expensive, very quickly.

One common concern was that a team can hurt its chances of winning if it allows an inferior pitcher to handle the higher leverage situations. Of course, not all saves are high leverage, but closers do generally have the highest average leverage among relievers.

Let’s imagine a team with two hypothetical relief pitchers — the veteran closer and the young setup man — in a battle for control of the ninth inning. In that February article, I estimated that a team could save $7-8 million by preventing its young setup man from picking up more than a dozen or so saves before reaching arbitration. So, how much better does the setup man have to be than the veteran for it to make financial sense to swap their roles?

To answer this question, I plugged in the numbers for these hypothetical relievers and generated the following table, comparing the gap in ERA- between the pitchers and the effect on WPA.

| Closer vs. Set-Up Man Comparison |

|---|

| Gap in ERA- | Change in WPA |

| 70 | 1.07 |

| 60 | 0.92 |

| 50 | 0.77 |

| 40 | 0.61 |

| 30 | 0.46 |

| 20 | 0.31 |

| 10 | 0.15 |

| 0 | 0.00 |

So, to get a difference of at least one win by WPA, the setup man occupying the RP2 slot would have to be 70 percent better than the veteran RP1. Even in situations where the young guy is clearly a superior option, the gap is not likely to be that large, unless the established closer completely falls apart.

For example, the gap between Cody Allen (with a 1.89 ERA) and John Axford, whose job he took away earlier this season, is “only” 33 points of ERA-. This accounts for roughly half a win over the course of an entire season. Since Axford held onto the role for the first quarter of the season, that makes the swap worth closer to three-eighths of a win. While that might be worth around $2.5-3 million on the open market, the Indians will pay the price when Allen starts going through arbitration in 2016. However, with the team over .500 with a shot at a Wild Card spot, it would be difficult to pull Allen from the ninth inning now.

Maximizing Bullpen Value

This offseason, the Athletics invested heavily in their bullpen, trading for Jim Johnson and Luke Gregerson, along with the $15 million they were owed in 2014. While a number of explanations were offered at the time, I wondered if certain teams might be in a better position to exploit high-leverage situations, and whether the A’s might be one of these teams.

I looked at a variety of team metrics from 2004-2013 and determined whether any had a significant correlation to average reliever leverage. I could include a table here with all of the results, but I’ll save you the time and tell you that there simply weren’t any significant correlations.

The two metrics that had the strongest relationship to reliever leverage were innings pitched by starters (R = 0.40) and ERA- of starters (R = -0.36). The first makes sense, as later innings tend to have higher leverage, and if starters aren’t going deep into games, it means that relievers are going to have to pitch in the less-meaningful middle innings of the game. The second is most likely tied to the first — the better your starting pitchers are, the more innings they pitch.

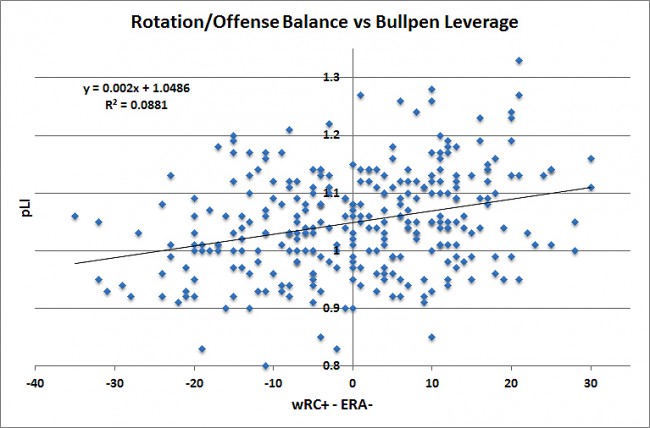

One hypothesis I had was that if a team was more balanced between its rotation and offense, the more likely the bullpen would be to see close games. To do this, I calculated the gap between ERA- and wRC+. (For example, a team with a rotation ERA- of 95 and a wRC+ of 105 would be 0, since both the starters and the offense are 5 percent above average. 90 ERA- and 100 wRC+ would be +10, meaning that the rotation is 10 percent better than the offense. A 105 ERA- and 110 wRC+ would be -15, meaning that the rotation is 15 percent worse than the offense.)

In theory, when the gap is smaller, the team should play more close games and the relievers should pitch in higher leverage situations. However, there turns out to almost zero correlation. In fact, the small trend was that teams whose rotation was stronger than their offense were more likely to have high-leverage innings thrown by the bullpen (R = 0.30). While this makes sense, it is also probably driven largely by the fact that these teams are more likely to have good starters who pitch deep into games (see above).

Conclusions

What did we learn today? First, evaluating relievers is tricky, and WAR doesn’t always tell the whole story. Also, the quality of a team’s bullpen will have a huge impact on the impact that an addition will have. Therefore, always keep leverage in mind when looking at both individual relievers and how they will contribute to a team’s bullpen.

Also, it’s extremely difficult to predict which teams will have higher-leverage innings for their bullpen to throw. Generally, if you have a solid group of starters who can throw quality innings deep into games, there will be high-leverage situations available to maximize the use of your relief corps. This strategy aligns with the idea that you shouldn’t invest significantly in a bullpen unless the rest of the team is good, given the short shelf life of relievers.

Lastly, and perhaps most importantly: the worse a bullpen is, the bigger the payoff from adding an elite reliever. While relievers can be volatile and it can never hurt to have depth, most teams only have two bullpen slots pitching high-leverage innings. Having two or three great relief options can be beneficial to a team, but once those slots are filled, a team would be wise to invest its resources elsewhere on its roster.

I would have liked for the article to comment on July trades for shutdown relievers. For instance, the Orioles picking up Miller from Boston.

At some point, Duquette and Showalter realized that, given their starting rotation’s tendency to not reach later into games, bullpen exposure risk is greater. Also, regarding leverage, the index ought to be “amped up” by a few degrees for teams in pennant races and the post-season. When the ALCS is on the line, but your best reliever has been over-extended, isn’t it great if your 2nd and 3rd best relievers are of similar quality to the best you have? (Britton, O’Day, Miller)

The point is that having high-level performance deep into the bullpen may be inefficient use of resources for an entire season (especially by a mediocre team), it is a great idea in the short run for a bullpen-reliant team expecting to go deep in October.

This is a great point. There are some things change (and others that don’t) when you’re investing in the bullpen in the middle of a season.

Generally speaking, all improvements are amplified, since the teams that are upgrading know that they’re in the playoff hunt and that every win counts (in addition to the increased importance of the bullpen in the playoffs). In this way, upgrading the bullpen in July does improve the team more, but not necessarily more than upgrading other positions.

With respect to the Orioles, my findings would seem to indicate that it might not have been wise for them to upgrade their bullpen. After all, they have had one of the better bullpens so far this season. However, when you look at the individual bullpen members, you start to see why this move made sense for the O’s.

Before they got Miller, they had four relievers with an ERA- below 80 (fitting for an RP1/RP2 slot). However, two of those relievers have an xFIP- of 100 or higher. Zach Britton is the only reliever with an xFIP- under 85 (and he almost certainly won’t be able to maintain a 77% ground ball rate). Essentially, after O’Day and maybe Britton, there are a lot of question marks, making acquiring another reliable arm for the back of the bullpen a better idea than it might initially seem.

Lastly, while the O’s bullpen has seen high leverage situations so far this season, that’s not necessarily a guarantee that they will continue to do so this season, since it’s not very stable. While having starters not go deep into games means they need more innings from the bullpen, it doesn’t mean they’ll be high leverage.

Overall very nice work and I appreciate the Orioles data in your response. I look forward to reading more fine articles from you!

Worth noting: Sky Kalkman mentioned via twitter that to get an accurate picture of the “value” of WPA, it needs to be adjusted to replacement level. Specifically, he said that a replacement level Starter is worth about -2WPA per season, whereas a replacement reliever is 0WPA. This makes sense, since a replacement reliever has has about a league average FIP-, while a replacement starter is about 25 points worse.

By the numbers, over the same 2004-2013 sample I looked at here, replacement-level relievers (WAR between -0.1 and +0.1) averaged -0.1 WPA. Replacement-level starters, on the other hand, averaged -1.6 WPA (this number is over 25 starts and 136 innings, which prorates to -2.1 over a full 32-start season).

This doesn’t really affect the research in this article, but as far as the catchy introduction, the starters should get a 1.5-2 WPA boost to calculate effective “WPA above replacement”, which would put them ahead of Holland and other top relievers.

Enjoyed the article a lot. I have a small logic switch to suggest in the Maximizing Bullpens section where you compare the wRC+ and ERA- of teams.

You say “One hypothesis I had was that if a team was more balanced between offense and rotation, the more likely the bullpen would be to see close games,” and then do all the wRC+/ERA- comparisons. And I agree with the quoted sentence, except I think the balance that would cause closer games is not having similarly good offenses and rotations, but having offenses and rotations that are the same difference from average but on opposite ends of the spectrum. For example, if a team has a wRC+ of 105 and a rotation ERA- of 95, yes the offense and rotation are both 5% above average but I would label that gap as 10, not 0. Because you start with a 5% above average offense, to create close games you would actually want a 5% below average rotation. And in the example with a 110 wRC+ and a 105 ERA-, I agree that the rotation is 15% worse than the offense but I think if you are looking at what causes high leverage situations you want to use a gap number of 5, since the rotation if 5% different than the offense when it comes to how many runs are scoring.

As an Orioles fan, I’m inclined to bring them up as an example: One of the reasons they’ve had so many close games in the past three seasons is that they’ve generally had a mediumly above average offense and a mediumly below average rotation. If their offense got closer to their rotation in skill level relative to the league they would actually have less close games because their offense and rotation would stop producing such similar run environments.

You’re completely right, thanks for pointing this out. I actually looked at both and must have chosen the graph/data above because I used the word “balance”. But what it should really be is similar runs scored versus runs allowed, which should happen when your offense is as bad as your pitching is good (or vice versa).

However, when you simply look at wRC+ minus ERA-, you still don’t see a correlation (R = -0.29, compared to 0.30 above). Although, what you REALLY want here is the absolute value of wRC+ minus ERA (since it doesn’t matter if your offense or pitching is better, just that the RS/RA is relatively even), but this once again gives us a low correlation (R = -0.28).

The key takeaway is that it’s extremely difficult to predict what kind of team will have more high leverage bullpen situations. The correlations show that being a better team (which is effectively what I showed above) correlates to bullpen leverage just as much as having close RS/RA numbers.

LASTLY, it’s possible that there are more high leverage innings for these teams, but that other lower leverage innings by the bullpen cancel these out when looking at the averages. I haven’t looked at bullpens on a case-by-case basis (as in, correlate offense/rotation to something like number of relievers with LI > 1.5), but I also can’t think of a good reason why this would happen.

Interesting article.

I’m surprised that there was no mention of the Win Curve and how that plays into the difference a reliever makes. Perhaps looking at team WAR and how that affects LI and high leverage situations. Maybe above average but not great teams like the Royals, Orioles, and Pirates have the most to gain by adding strong relievers. Seems like great teams would benefit a lot as well, but would have a little more margin of error. But perhaps the fact that a great team would supply more leads might mean more potential WPA, I don’t know.

I didn’t explicitly mention the win curve, but it is obviously a big factor in determining when to invest in any aspect of a team. This might be magnified in the bullpen, as relievers are the least predictable asset.

As far as looking at team WAR, I probably should have been more clear about the factors that didn’t have a strong correlation to reliever leverage. Team WAR was one of them (R = 0.17, and the relationship doesn’t get any stronger if you use a quadratic trendline that allows the middle “average” teams to have higher leverage).

Team wRC+ (R = 0.03) also didn’t have any impact, although Defense (R = 0.23) had one of the higher correlations for the variables I considered. I’m open to running more numbers to look for correlations, but the only relevant team metrics that had R > 0.3 were Rotation IP and ERA.

“The fact that every average bullpen slot is capable of doing this tells us that it has more to do with the nature of the bullpen than the skill of the pitchers. ”

You’re only looking at relievers that threw 40 innings or more. Relievers that fail don’t throw 40 innings in a season. The reason why your numbers show that bullpen pitchers are successful is because the ones that did poorly simply aren’t in the sample. If you only looked at starters that threw 120 innings or more then their numbers would look good also (although not as good as the relievers because teams have more relievers than starters in the minors).