Measuring & Managing the Value of Ballclubs (Part 1)

Every year as free agent salaries explode, journalists and analysts try to find a means behind the madness that explains the inextricable growth of payroll. One reason posited is that as more money flows into the game the value of baseball clubs continues to grow astronomically, allowing owners to indulge in wage largesse.

The theory is that owners don’t have to turn a profit because they make money purely through capital appreciation and use that as the basis to sign the latest and greatest free agents. Mix new superstars with your existing crop of talent and the team is in line to cover itself in postseason glory. A World Series win would do wonders for the bottom line, which would cause the value of the club to grow even faster. So it goes. It is difficult to fault the logic, but when all 30 owners are driving to the same end and there are only eight postseason slots, losers will outnumber winners.

It is with this thought that I present a four-part series on ball club valuation. In this opening piece, I’ll look at the relationship between payroll growth and ball club value over the last 20 years or so, using data from Forbes. In the second part, I’ll spend more time with the Forbes data, poking around under the hood to see how robust the methodology is.

In the third part, I will take a look at different valuation techniques and try to value the Milwaukee Brewers. Why the Brewers? Data are difficult to get and it just so happens that there is quite a bit of publicly available info on Bud’s old team. These three comprise what I call “Measuring Value.” In the final installment I want to explore why similar clubs can have wildly different valuations and give some thought as to what owners can do to maximize the worth of their franchises—this I term “Managing Value.”

This four-part series only scratches the surface of what is a much wider topic. Over the coming few months I’ll return to this subject with plenty more detailed analyses and insights.

Let’s get started.

Valuation 101

Before we launch into this stuff it’s worth spending a little time on the basics of valuing a ball club, or any other asset for that matter. The subject is extremely complex and technical, but in short the value of any asset is the present value of all future cash flows. So what does this mean? Let’s run through an example. If I give you $100 a year every year for the next five years, what is that worth to you today? It obviously depends on a number of factors, the most important being what you could make by investing that money elsewhere.

If you thought that you could invest that money in an instrument (eg, a bank account) that returned 5% interest (risk-adjusted) per annum, then a little math tells you that the worth of your asset (ie, the present value of $100 for the next five years) is about $380. In other words you’d be willing to pay a maximum of $380 for that asset. And that is the crux of valuation. Make sure you keep this concept in mind while trawling through different aspects of valuation as it is one I’ll keep referring back to.

Now let the games begin!

Ball club Valuations

Who’s heard of Forbes? Most people, I suspect. They are the guys who publish the eponymous rich list every year so we can find out whether Bill Gates accumulated more treasure than Warren Buffet did. The rich list isn’t the only perennial list that our friends print. They also publish valuations for every major league franchise. How they arrive at their numbers is a bit of a conundrum—one that’s best left for another day.

Take a look at the most recent list, which was published in 2006 for the 2005 season:

Rank Team Value % Change 1 New York Yankees 1026 8 2 Boston Red Sox 617 10 3 New York Mets 604 20 4 Los Angeles Dodgers 482 14 5 Chicago Cubs 448 12 6 Washington Nationals 440 42 7 St Louis Cardinals 429 16 8 Seattle Mariners 428 3 9 Philadelphia Phillies 424 8 10 Houston Astros 416 17 11 San Francisco Giants 410 8 12 Atlanta Braves 405 6 13 Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim368 25 14 Baltimore Orioles 359 5 15 San Diego Padres 354 8 16 Texas Rangers 353 8 17 Cleveland Indians 352 10 18 Chicago White Sox 315 20 19 Arizona Diamondbacks 305 7 20 Colorado Rockies 298 3 21 Detroit Tigers 292 22 22 Toronto Blue Jays 286 34 23 Cincinnati Reds 274 8 24 Pittsburgh Pirates 250 15 25 Kansas City Royals 239 28 26 Milwaukee Brewers 235 13 27 Oakland Athletics 234 26 28 Florida Marlins 226 10 29 Minnesota Twins 216 21 30 Tampa Bay Devil Rays 209 19

I suspect the order won’t shock too many people. What we perceive as large-market clubs dominate the upper echelons while the minnows bring up the rear. If you gave the table above more than a cursory glance, the third column, which tells us that baseball is in a rather rude state of health, may have caught your attention. The average franchise grew in value by an astonishing 14% between 2004 and 2005, outperforming almost every other asset class. To put it another way, Frank McCourt trousered an extra $60 million in paper capital gain last year simply by owning the LA Dodgers. The same cash in a bank account would have netted $15 million, or $30 million tops in the stock market.

These data show that collectively baseball became a lot richer last year. To see the permanence of this trend take a look at how the values of all major league franchises combined have risen since 1990 (expansion franchises ignored).

Year Value ($B) Year % change 1990 3,150 1991 3,021 -4% 1992 2,830 -6% 1993 2,805 -1% 1994 2,885 3% 1995 3,000 4% 1996 3,458 15% 1997 4,970 44% 1998 5,627 13% 1999 6,141 9% 2000 7,029 14% 2001 7,683 9% 2002 7,982 4% 2003 7,975 0% 2004 9,002 13% 2005 10,256 14% CAGR since 1990 8.2% CAGR Since 1995 13.1%

In the early 1990s, as the US economy emerged from its recession and the players’ strike took hold, valuations stayed static. It was only after the labor dispute ended that the value of ball clubs started their stratospheric climb. In all, year-on-year capital appreciation over the period was a healthy 8%; after 1995 it was a hedonistic 13%.

Yikes, that is a lot of moolah! So, what happens to it all?

The Link to Payroll

One obvious beneficiary of this largesse is player wages. But does all the capital appreciation go straight into the players’ pockets, or is there something left for the owners to cream off the top?

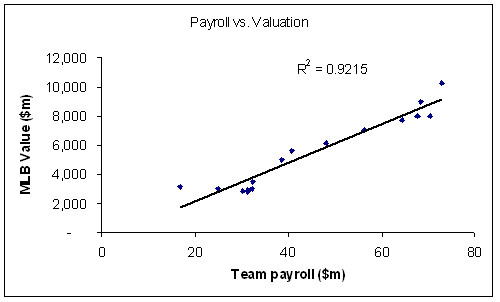

The graph shows average payroll on the x-axis against value on the y-axis. Unsurprisingly there is a strong relationship between the two. The R squared is 0.92. Closer examination of the data show that there is actually a small lag effect. For instance, in the early 1990s valuations were static but payroll was moving along at a 20-30% clip. It was only a couple of years later that General Managers reined in spending. Likewise, when valuations started to surge in 1995, it took another two years before teams loosened the purse strings.

The model predicts well what is happening this year. Since 2004 average payroll has risen by only 2% a year, but values have accelerated at 15% a year. Based on that we’d expect 2007 to be a bumper payroll year and the current goings on in the free-agent world definitely support that.

There are a couple of watch-outs though. First, is the consideration that the values we are using come from Forbes. If sabermetrics has taught us one thing it is to be skeptical about what we see and hear. I’ll look at how much stock we should put in the Forbes data in part two.

Second, if it is not obvious now it will be by part three, but there is an inextricable link between revenue and value. All else being equal, the more revenue a club generates the higher its profits are and the more it is worth. Values are being driven up as a result of money flooding into the sport from lucrative TV deals and rocketing ticket prices. The link is more subtle that you may think. For instance, if a club signs a new TV deal we’d actually expect value to increase ahead of revenue.

Why? Valuation 101 said that the worth of an asset is the present value of all future cash flows. A new TV deal implies not only higher revenues today but also in the future. The value reflects this expected increase in revenue immediately although it takes several years before the full impact of this new revenue is realized. The lag trend we saw earlier is partly because of this interaction between revenue and value. Taken to its logical conclusion there is an argument that GMs could be even more aggressive in the free-agent market than they already are. It would be the same as you or I borrowing against the rising value of our homes to fund renovation projects or other frivolous activities.

Either way value and payroll are closely related—so, big deal; isn’t that what we expected? Well, yes, to a point at least. Don’t forget that owners continually bleat about how spiralling wage bills result in impoverished franchises. Poor owners! Although that view has been largely discredited in recent years, the data above prove it to be emphatically false. In fact the Forbes data say that valuations have risen faster than mean payroll over the last 15 years. Total payroll as a percent of total value has dropped from 24% to 22% over the last decade. Collectively the owners are dripping with lucre.

Let’s Talk Teams

Enough of looking at data in the aggregate, let’s look at what has happened to the value of individual franchises in this period. Which have increased the fastest? Have a look at the valuations for all teams from immediately after the strike in 1995 to today:

Team 1995 ($m) 2005 ($m) CAGR Expos / Nats 68 440 21% Padres 67 354 18% Yankees 209 1026 17% Mariners 92 428 17% Mets 131 604 17% Red Sox 143 617 16% Astros 97 416 16% Phillies 103 424 15% Angels 90 368 15% Pirates 62 250 15% Cardinals 112 429 14% Giants 122 410 13% Brewers 71 235 13% Dodgers 147 482 13% Cubs 140 448 12% Royals 80 239 12% Twins 74 216 11% Indians 125 352 11% Reds 99 274 11% Tigers 106 292 11% Rangers 138 353 10% Braves 163 405 10% Athletics 97 234 9% Marlins 98 226 9% Rockies 133 298 8% White Sox 144 315 8% Orioles 168 359 8% Blue Jays 152 286 7% Devil Rays 209 Diamondbacks 305

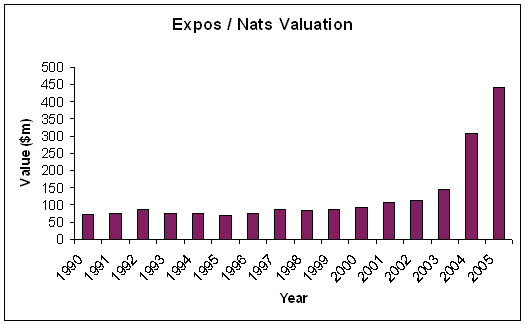

The table is sorted by10-year CAGR. Interestingly the Nationals are top of the tree because thrashing the timber in the capital is far more lucrative than it is in some Canadian outpost. See if you can guess the relocation year from the graph below?

Okay, you don’t have to be Einstein (or even know anything about baseball) to decipher that it was 2004. No wonder Bud Selig and the MLB owners were so keen to buy the Expos—it was a license to print money. The extent to which local markets drive value is interesting and is something we’ll explore in more detail in part four.

What other trends can we detect? Let’s pick out a few examples.

You’d think that with 10-15% annual rises in franchise value everyone would be coining it. Not so. Look at how the Tampa Bay Devil Rays’ value has changed since their expansion in 1998. Forbes initially pegged them at $225 million, or around the average in that year, but by 2003 their value had slumped to $150 million despite the market’s Everest-like ascension.

Devil Rays Year Value ($m) 1998 225 1999 163 2000 150 2001 142 2002 145 2003 152 2004 176 2005 209

Another interesting example is my team, the Atlanta Braves.

Atlanta Braves Year Value ($m) Payroll ($m) 1990 74 10.9 1991 83 21.2 1992 88 32.9 1993 96 43.9 1994 120 40.3 1995 163 47.9 1996 199 53.6 1997 299 52.1 1998 357 61.7 1999 388 79.3 2000 407 84.5 2001 424 91.8 2002 423 93.5 2003 374 104.6 2004 382 90.1 2005 405 86.5

The Braves’ value peaked in 2001 & 2002 at $424m, which was also close to the time that their payroll peaked. Coincidence? I don’t think so. Remember the 2003 valuation was published in Forbes in 2004 after Time Warner clamped down on payroll. We said earlier that value today is based on our future expectations of revenue and profit. Forbes probably thought that the Braves dynasty was coming to an end and so would be worth less. The rebound in 2005 could be because Schuerholz continued to defy the sceptics with on-field success while juggling more limited resources. With the Braves under the hammer for anywhere between $450m-$600m (the final number remains a mystery) it seems as though Forbes’ estimate could have been a tad conservative—we’ll find out soon.

One final thing to mention is that on-field success doesn’t appear a path to financial utopia. Two of the best-run teams in the majors, the Twins and the Athletics, continue to languish at the bottom of the valuation table. Perhaps the old adage that you have to spend money to make money is true after all!

Value ($m) Year Athletics Twins 1990 116 81 1991 115 83 1992 124 95 1993 114 83 1994 101 80 1995 97 74 1996 115 77 1997 118 94 1998 125 89 1999 134 91 2000 149 99 2001 157 127 2002 172 148 2003 186 168 2004 185 178 2005 234 216

I’m not going to go through each individual club but if you want to look at valuations over time you can download a spreadsheet here.

Takeaways and Next Up

So, what have we learned?

1) As more money comes into baseball franchise values increase (duh)

2) This feeds through into higher payroll (duh again)

3) Extraneous factors affect value, we have discovered four:

- Poor performance can destroy worth

- A winning team doesn’t equal instant wealth

- A change in future expectations (either money or performance) will affect value

- Relocation can radically transform value

However, this list certainly isn’t complete. That will be the task of future articles but before we move on to that we need to deal with a pressing question: Namely, how does the Forbes methodology work and is it a good judge of value for a baseball club?

I’ll provide those answers in a couple of weeks.

References & Resources

Obviously Forbes is a great (and only) source of valuation data and the Lahman database provided all the salary information that I used. Thank-you both!