Rube Bressler Redux?

[T]he game hasn’t changed … I see the same type pitchers, the same type hitters…I am a little more convinced than ever that there aren’t as many good hitters in the game … They talked for years about the ball being dead. The ball isn’t dead, the hitters are, from the neck up.—Ted Williams in The Science of Hitting

It was October 3, 2000, top of the third inning as the Cardinals faced the Braves in the first game of the Division Series at Busch Stadium. On the mound for the Cardinals was Rick Ankiel, who already held a 6-0 lead over Greg Maddux, who strode to the plate. What followed, a scene that Cardinals fans have tried desperately to forget, was a walk, popup, wild pitch, wild pitch, walk, wild pitch, strikeout, walk, wild pitch, single, wild pitch, walk, and finally a single before Tony LaRussa pulled Ankiel in favor of Mike James. The Cardinals went on to win the game 7-5 and sweep the series. Nine days later Ankiel started game two of the NLCS against the Mets and lasted just two-thirds of an inning, giving up a double, three walks and throwing two wild pitches.

Those two games forever changed the fortunes of Rick Ankiel and the Cardinals.

Fast forward five years. As Brian Gunn chronicled in March of this year, Ankiel announced his retirement from pitching after a horrible simulated game against his teammates in spring training, in which he threw just three strikes in 23 pitches. His career record stands at 13-10 in 51 games, 242 innings pitched and 3.90 ERA. At that time Brian thought it best to consider Ankiel retired from baseball, since his career stats as a hitter beyond the low minor leagues were anything but impressive. Today I’ll pick up the story where Brian left off.

To the River and Back

I was in eastern Iowa this summer near the banks of the mighty Mississippi and picked up the Quad City Times sports section. There on the front page was an article describing the transition of the Quad City Swing’s (the low-A, Midwest League affiliate of the Cardinals, who play in the beautiful and newly remodeled John O’Donnell Stadium right on the river) newest outfielder, Rick Ankiel, who had joined the club on May 23. In the article, Ankiel noted how different it was getting prepared to play everyday rather than every fifth day and how he was just starting to feel comfortable in the outfield.

This was the second stop for Ankiel as he started the year at Double-A Springfield, but did not fare well in his first 60 at-bats, getting off to a 1-for-20 start and hitting around .160 before getting sent down. With the Swing he continued to improve and wound up hitting .270/.368/.514 with 10 doubles and 11 homeruns in 212 plate appearances. His strikeouts were a bit high (37), though he showed a little patience at the plate, collecting 27 walks.

That good showing in the Midwest League earned him a trip back to Springfield on August 3, and this time it appears he took advantage of it. In the remainder of the season he would hit .300 with 10 homeruns and drive in 28 runs in the 28 games he played, including a 3-for-4 performance with two homeruns and three RBI on the final day of the season. His late season surge even prompted some talk of a September call-up.

His combined line at Springfield was .243/.295/.515 while overall for the season he hit .259 with 17 doubles, 21 homeruns, and 75 RBIs in 321 at-bats and 85 games. Although he still has a long way to go, I’m sure he and probably the Cardinals viewed this season as a success.

Late in June Ankiel was asked about making the transition from pitching to the outfield.

“Not very many people have been successful at it,” he replied. “To conquer that quest would be very self-fulfilling.”

The question is, how likely is it that Ankiel can actually conquer that quest?

The Quest

To put some historical perspective on Ankiel’s quest I decided to see how many other players had followed his new career path. To my knowledge there have only been five players since 1900 that started their careers as pitchers and ended up being position players and totaled more than 50 games pitched and 50 games played at other positions in the major leagues. Can you name them?

There would be others who pitched less than 50 games in the majors or who played less than 50 games at other positions including George Sisler, who pitched 15 games as a rookie in 1915, became a full-time first baseman the next year and ended up with 2812 hits, Buzz Artlett, who was a minor league version of Ruth in the Pacific Coast League, Lefty O’Doul, Sam Rice, Charlie Jamieson, and Jack Graney, who were all minor league pitchers. This road was also followed by plenty of players prior to 1900, including Cy Seymour (1896-1913), John Ward (1878-1894), George Van Haltren (187-1903), and Bobby Wallace (1894-1918), to name a few.

And there was also the curious case of Johnny Lindell, who came up as a pitcher in 1942 for the Yankees and pitched 52.2 innings with a 3.76 ERA. He quickly converted to the outfield and enjoyed some success, hitting .300/.351/.500 in 1944 for the Yankess. However, when his effectiveness as an outfielder had diminished by 1950, he transitioned back to pitching and was called up by the Pirates in 1953. He responded with 175.2 innings and a 4.71 ERA. He also pitched a little for the A’s that same season before retiring in 1954 at the age of 37.

James and Gould

What are we to make of these transitions? As Bill James has pointed out, many of these transitions happened in the years from 1915-1925. In The New Bill James Historical Abstract James posits that one of the reasons this may be the case is that the value of hitters increased dramatically during this period, making it a more attractive option for players. By that same reasoning, the recent offensive surge may have the same effect, and so is it possible that Rick Ankiel is the vanguard?

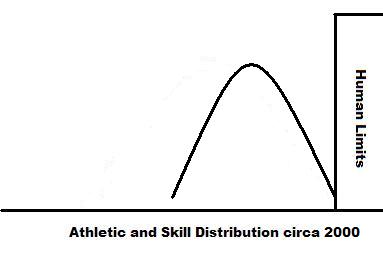

While I don’t totally discount this theory, and it may indeed have played a role for these players, I doubt we’ll be seeing the second coming of Rube Bressler on a regular basis. My view is that these transitions essentially ended after the war not because of the relative value of offense and defense but rather because of the increasing level of play that comes closer to the “right wall” of human ability, coupled with the stabilization of the game itself. In other words, over time baseball players, like other athletes, including sprinters and swimmers, have become better and as the level of play has increased, it has had the side effect of decreasing the variation among players. In the late Stephen Jay Gould’s essay on the disappearance of the .400 hitter, he illustrated this with two graphs like those shown below, where the area under the curves represents a measure such as batting average.

Over time we’ve transitioned from the first graph to the second. One effect of living in the world of the graph on the bottom is that there is less space between those who are on the left side of the curve and those that are on the right. For players like Ruth, Wood, Bressler and company there was therefore more opportunity to make the transition because good athletes of their ilk could more easily excel beyond the more numerous lesser athletes that populated baseball in the early part of the century. In the words of Gould, a modern player like Wade Boggs is at a disadvantage over someone like Willie Keeler because “average play has so crept up on Boggs that he lacks the space for taking advantage of suboptimality in others.” A game populated with athletes closer to the right wall leaves less space for those transitions to take place.

This effect was likely aided by the fact that the game was not as stable and therefore as specialized as it is today. Over time, as more knowledge about effective ways to play the game were discovered, a higher degree of skill was required in both hitting and pitching in order to reach the major leagues, and because there is only a limited amount of time available for any athlete, they will tend to specialize earlier in order to get the most out of their ability. As a result, by the time a pitcher flames out in today’s game, he’s likely so far behind in acquiring the skills needed to excel in hitting at the professional level that it’s a lost cause.

So what does this mean for Ankiel? While there may have been modern pitchers like Ken Brett, Tim Lollar, and Rick Rhoden who could have made the transition, the competition and specialization of the modern game makes it an uphill battle to say the least. I wish him luck on his quest and hope he does become the next Rube Bressler.

References & Resources

SABR.org – I found some of the players mentioned in the article from a lively discussion recently on SABR-L

3 Nights in August – by Buzz Bissinger contains a short biography of Rick Ankiel

Triumph and Tragedy in Mudville – by Stephen Jay Gould contains a reprint of the essay “Why No One Hits .400 Anymore”