The 1961 Expansion Draft and Baseball’s Anti-competitive History

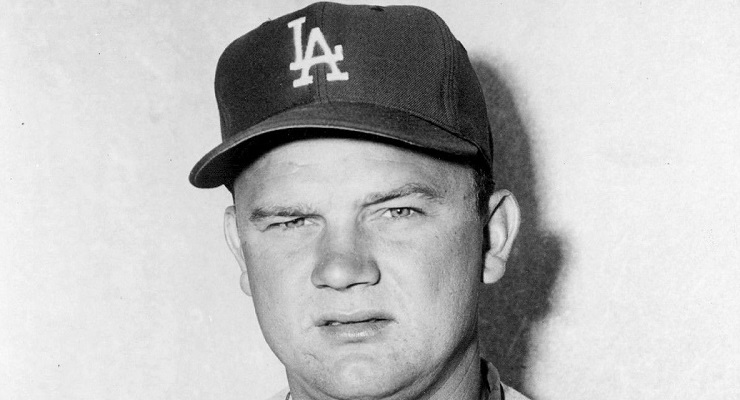

Don Zimmer was a “premium player” during the first expansion draft. (via Public Domain)

The most successful expansion franchise in baseball since the Angels and Rangers (nee Senators) joined the American League in 1961 has unquestionably been the New York Mets. The Mets’ two World Championships puts them atop the list along with the Marlins and Blue Jays, and their four pennants top the list — among the 13 other expansion franchises, only the Royals have three league championships in their history.

The Mets as lovable losers or bumbling failures is more cultural myth than truth. It’s a myth that sustains itself for a number of reasons: the club plays in the shadow of the Yankees and their 28 championships; when the Mets fail, they fail spectacularly, as seen in their collapses down the stretch in 2007 and 2008; the horrific stewardship of the Wilpon family and the club’s involvement in the Madoff Ponzi scheme have set the franchise back years and eliminated what should be huge spending power given their prime location in New York.

But the Mets-as-losers myth would be nothing without the legendary 1962 Mets, a 40-120 team that was outscored by 331 runs — over two runs per game. Those Mets had just two regular hitters (Frank Thomas and Richie Ashburn) who posted a better OPS than the league average, and not a single pitcher with over 20 innings pitched with a better ERA than the league average. The 1962 Mets were a new kind of awful, a kind of hopeless baseball team not seen since the 20-134 Cleveland Spiders of 1899. This kind of terrible baseball was supposed to be extinct, but the 1962 Mets brought it back to life.

The 1962 Mets weren’t the fault of anybody in that organization, from owner Joan Payson down to 35-year-old reliever Clem Labine (four innings pitched. five earned runs in three appearances). They were doomed from the moment National League President Warren Giles announced that the 1961 expansion draft would take place the day after the completion of the World Series. “On paper it read like any other league announcement,” Jimmy Breslin wrote in his book on the 1962 Mets, Can’t Anybody Here Play This Game? “But it was really was robbery in the daytime.”

The year before, the American League had held the first ever expansion draft. It took place in December—after teams had made decisions on which minor league players to call up to protect them from the Rule 5 Draft. As a result, the Angels and Senators had their pick of a number of talented young players when teams submitted their lists of available players. The Angels nabbed a couple of young pitchers in Ken McBride and Eli Grba—25 and 26 respectively—who each recorded over 200 innings pitched and an ERA+ over 100 in 1961. They also snagged 20-year-old righty Dean Chance from the Orioles, who posted a 130 ERA+ in 206.2 innings in his first full year in 1962 and won the Cy Young Award with a 1.65 ERA (200 ERA+) in 278.1 innings two years later.

These players were good enough to get the Angels to 70 wins in their inaugural season and 86 victories in their second. The Mets would not be so lucky. By pushing the expansion draft date forward by two months, National League owners made a repeat of the damage done by the Angels in the first expansion draft impossible. With the earlier expansion draft date, the list of players available to the Mets and fellow expansion franchise Houston Colt .45s included none of the hot young talents that made the Angels early success possible. Instead, the new franchises were picking from the ranks of aging veterans, utility players and swingmen who would have certainly been released to make room for protected minor leaguers come December.

On Oct. 10, 1961, after Yogi Berra, Whitey Ford and the Yankees polished off the Reds in a tidy five-game World Series victory, the Mets and Colt .45s filled out their rosters for the 1962 season. Both teams were required to select 16 players at a price of $75,000 each and four “premium players” at $125,000 each. Among the “premium players” were Colt .45s selection Joe Amalfitano, a 28-year-old third baseman with a .263/.330/.333 line and three home runs in 260 games played for the Giants; Don Zimmer, then a 31-year-old utility infielder with a .238/.291/.378 career line in 697 games between the Dodgers and Cubs (and an inexplicable All-Star Game appearance in 1960 behind a .252/.291/.403 batting line); and 25-year-old pitcher Jay Hook, who had posted a 5.23 ERA in 56 starts for Cincinnati and allowed a league-high 31 home runs for the Reds in 1960.

And remember, these were the premium players.

For the right to fill their new rosters with these players (and many who were far worse), Mets owner Payson shelled out $1.8 million to the rest of the National League—roughly $14 million in today’s dollars. “I want to thank all those generous owners for giving us those great players they did not want,” Casey Stengel said of the expansion draft. “Those lovely, generous owners.”

Breslin was even more blunt:

It was the kind of scheme only some sneak businessman could come up with. Baseball has plenty of these. What makes it worse is that the scheme was obviously designed to harpoon money away from Joan Payson. She was coming in with millions, and everybody thought it would be smart to grab some of it. Here was a lady coming into baseball for sport. More important, she was coming to stay. She would be an important addition to the game. So what do they do? Why, rob her.

The excuse offered is, of course, that in this country you’ve got to make it on your own. We don’t have socialism, so in business, expect help from nobody.

It’s an ironic stance for the National League’s businessman to take considering how baseball works and what they were doing to Payson and Colt .45s owners Craig F. Culling Jr. and Roy Hofheinz. In reality, baseball’s owners were doing the same thing they had done for years, something cribbed from the great finance moguls of the late 1800s like J.P. Morgan: the elimination of competition from the market. Competition is supposed to be the lifeblood of capitalism. It’s the source of the “invisible hand” Adam Smith claimed guides the capitalist economy. For baseball’s owners to claim capitalism as they force new entrants to the league to pay nearly $2 million for players worth a fraction of that is rich.

The Mets and Colt .45s entered 1962 so far behind as to make competition impossible. The Colts were a forgettable kind of awful. They finished 64-96 and saved their worst baseball for the end of the season—the Colt .45s were 31-36 with a positive-two run differential on June 22, the high-water mark of their season. A 16-3 Houston victory over the Mets that night sent New York to 18-48, already a cool 5.5 games “ahead” of the Cubs for the worst record in the National League. Houston proceeded to go 33-60 in the final 93 games and actually scored 25 fewer runs than the hapless Mets. Roman Mejias was the only Colts regular to slug over .400, and Turk Farrell—one of the premium players in the expansion draft—was the only Colts starter with an ERA+ over 100.

Both squads were awful again in 1963, as none of the sort of young gems that helped the Angels contend in their second season were present in the slim pickings offered up to the Mets and Colts. The Mets improved by 11 games to go 51-111 and finished last in the National League by 15 games—to the Colts, who dropped to 464 runs scored, worst in baseball by 37. The situation was disastrous enough the National League held a special draft in 1963 for the Mets and Astros.

It didn’t help much. The Mets took Jack Fisher from the Giants, and Fisher went on to allow the most earned runs in the National League in three out of the next four seasons. The Colts grabbed Claude Raymond from the Milwaukee Braves. He was a steady reliever who made an All-Star team in 1966 but hardly moved the needle for a languishing franchise. Houston didn’t turn in a winning season until 1972. The Mets lost 100 games in five of their first seven years before the miracle season of 1969.

In 1965, Branch Rickey wrote in his autobiography, “Ownership must eliminate the bonus.” Rickey explained, “Something for nothing may be an objective among many slothful, unthrifty elements of our people, who seem to believe that the world or the nation or the community owes them a living, but it has no place in baseball because it tends to damn the player, wreck the club, and bankrupt the owner.” In 1964, Rick Reichardt signed a record $205,000 signing bonus with the Angels, blowing past Bob Bailey’s $175,000 bonus with Rickey’s Pirates in 1961.

According to Baseball-Almanac, at least 11 players signed bonuses over $100,00 between 1950 and 1965. The first was another Rickey signing, Paul Pettit. Pettit was a disastrous signing, as he appeared in just 12 games over two seasons in his career. Rick Monday became the first player ever taken in the major league draft in 1965, when the Kansas City Athletics selected him. His signing bonus checked in at $100,000. No more Paul Pettits destroying Rickey’s best laid plans and bankrupting owners!

The draft, in this sense, was a huge success. It did not eliminate the bonus as Rickey requested. But by forcing draftees to negotiate with only one team—thus eliminating the previous competitive aspect of scouting and signing—bonuses were significantly suppressed. Rick Reichardt’s 1964 bonus was just $30,000 shy of what 1988 first overall pick Andy Benes earned. The average franchise value, meanwhile, went from $5.58 million in 1960 to $110 million by 1991—a 20-fold increase, effectively none of which was seen by young players entering the league.

Drafts, expansion or otherwise, are just one of a number of anti-competitive measures organized baseball has used to entrench its power. The reserve clause, the “chain-store” minor league system, hard slotting, amateur bonus pools—all of these exist to keep owners from bidding each other up on valuable young players, players who we know would earn significantly more on the open market given the assets teams are willing to deal for them.

These anti-competitive measures have worked wonders for established baseball owners and executives. What about everybody else? What about baseball fans in New York or Houston who hoped to see competitive National League baseball in the 1960s? What about people who want to watch teams in minor league cities try to win baseball games rather than develop players? And what about the minor leaguers toiling in the farm systems for peanuts, both here at home and abroad?

Lou Kahn, one of Rickey’s players in the Cardinals farm system over two decades, told Kevin Kerrane, author of Dollar Sign on the Muscle: “He’d sign kids and never turn in their contracts, and watch how they did for a month in Class D, and if they didn’t look too good they’d get cut with no obligation,” a common practice in baseball’s early days. “My high school buddy got cut that way: his ass was stranded 500 miles from home. No fare home or nothin’. Rickey didn’t give a s***.” Rickey’s belief in the constructive power of competition apparently didn’t include the front office or the owner’s booth.

As far as baseball’s anti-competitive measures go, the 1961 Expansion Draft was relatively tame. It was not an assault on the labor rights of athletes. It was merely a method to bilk some cash from some fellow rich people and subject two National League cities to utterly uncompetitive baseball for nearly a decade. But it shows the way organized baseball operates, and how those in charge turn the baseball world into a laissez-faire paradise, a hyper-competitive Darwinian capitalist environment—for everybody, that is, but themselves.

Outstanding, Jack.

“The Mets as lovable losers or bumbling failures is more cultural myth than truth.”

I’m guessing you’re not a Met fan, right? Only someone looking in from the outside could write that with a straight face…

I tend to agree with Randy. From 1962 thru 1983 the Mets basically had one good team: the Miracle Mets of 1969. The 1973 pennant was a fluke of an extremely balanced and not especially good NL East. The only other competitive season was 1970 when they finished 6 games back; every other year in the range had the Mets at least 10 games back of first and usually a lot more than that. They weren’t always terrible – there are a half dozen or so 500-ish teams in there – but overall it was a bumbling franchise until they came up with Gooden, Hernandez, Strawberry, etc. Since then they have also had some patches of very badness: 1991-1996, 2001-2004, and 2009-present. Combine that those recent back-to-back collapses and a history of horrible trades (Nolan Ryan for Jim Fregosi, etc.). Being a Mets fan is an experiment in semi-masochism. At least they do have their moments of brilliance unlike, say, Seattle.

“Being a Mets fan is an experiment in semi-masochism. At least they do have their moments of brilliance unlike, say, Seattle.”

Mets .478 all-time winning % (7 playoff appearances, 1962-current)

Mariners .468 all-time winning % (4 playoff appearances, 1977-current)

Yeah, being a Mariners fan would suck way worse than being a Mets fan. By about .010

“Being a Mets fan is an experiment in semi-masochism. At least they do have their moments of brilliance unlike, say, Seattle.”

Mets .478 all-time winning % (7 playoff appearances, 1962-current)

Mariners .468 all-time winning % (4 playoff appearances, 1977-current)

Yeah, being a Mariners fan would suck way worse than being a Mets fan. By about .010 % points.

Actually, that cements the point of the Mets being a bumbling franchise.

However, there is a big difference between making the playoffs and winning the pennant. For all their bumbling the Mets do have 4 flags that are spaced fairly well time wise. A Mets fan can expect that no matter how bad the team is now there is a real chance of winning another one in the near future. Seattle has never made the World Series. It makes a big difference.

To discuss the subject at hand, Major League Baseball has never been a “laissez-faire paradise.” I suspect that someone somewhere has claimed as such at some point, but, no, it never was. In fact I seriously doubt it could ever be even if everyone wanted it to be. The key problem is while the teams in the league are competing against each other on the field, they are not really competing against each other economically except in a limited sense.

In a working free market there are two common phenomenon: businesses that fail to provide the goods/services to their customers fall out (bankruptcy, purchased by competitors, etc.) and new businesses enter into the market to compete. That’s not baseball. The Yankees, as much as their fans may love the idea, are not trying to bankrupt the Red Sox. Beat them every year? Sure. Destroy them utterly and rejoice as their assets are sold off? No. Furthermore, new teams are not joining the league whenever some owner feels that Buffalo or Las Vegas or Troy is capable of sustaining an ML franchise. To put it differently, the major league teams are in cahoots, friendly rivals if you will, a cartel of sorts.

There is competition going but that involves MLB as an entity. MLB is competing for entertainment dollars not only from other sports (NFL, MLS, WNBA, professional lacrosse, etc.) but also other forms of entertainment like movies, television, video games, hanging out at the beach, travel tourism, etc. In this market competitors do go bankrupt and enter in the market on a regular basis. The closest that MLB actually competes in the baseball market would be against the indie leagues and college, both of which serve as feeder systems to the MLB and therefore are tolerated, and perhaps some foreign leagues with very little territorial overlap. MLB has not had to seriously compete against another baseball league since the Federal League with relatively minor incursions of the Mexican League and Continental League at various points.

Professional baseball was a lot closer to a free market back in the early years before there were leagues. Each team was more or less an independent company trying to make money. But even then it was not a true free market as any team would need other teams to play against so it was in a team’s interest to not completely wipe out the competition. A monopoly meant death. When the National Association came along it was certainly more free market than the present day MLB with minimal barriers of entry and teams controlling their own schedules, but it was also a fiasco. You had teams in big cities playing little podunks, teams scheduling games and then refusing to play them, the strong teams extorting the small teams for more of the gate, teams dropping out mid-season, etc. The baseball business needed more structure to work and hence the National League. This is not unusual. Most capitalist approving economists realize that some markets are most efficient as monopolies in which case all you can do is regulate them to minimize the damage.

But, yeah, owners can be greedy. So can their employees as a myriad of companies destroyed by their unions can attest.

As to the expansion draft, did the Mets have to pay anything additional to join the league? Then the costs here was essentially their expansion fee, nothing especially nefarious other than the talent was awful. The draft itself was a mess but the AL’s expansion draft the prior year was also a disorganized mess. It’s not like MLB had done this sort of thing before and I suspect if they knew it was going to be this bad they would have done it differently. Never attribute to malice that which is adequately explained by stupidity.

Nice post, Paul G. I completely agree. I also enjoyed the article, as the history was interesting and informative.

However, the author (and perhaps, Jimmy Breslin) seem confused in their own mind about what “capitalism”, “socialism” and free markets actually mean. To the point where they contradict themselves and argue both sides of the issue within a few moments of each other.

Once you’ve agreed to things like a draft to divide up a pool of available players, group decisions to allow only fee-paying new entrants to play you in a pre-arranged schedule, etc. you’ve already advanced well past notions of “free markets”. The fact that baseball enjoys a formal anti-trust exemption should be evidence of that in itself.

And presumably, the woman who owned the Mets was urbane, intelligent, had been informed of the rules and still decided that entering the socialist club was worthwhile. More power to her. To ascribe the outcome to anything else like nefarious “capitalist” motives actually belittles her. As well as perhaps, starts to reveal little inklings of political leanings and corresponding bias in the writers.

And really, as long as people are engaging in such transactions voluntarily and not at the point of a gun, who cares? Sometimes building little socialist clubs like this does no real harm and can produce a more entertaining product. That’s exactly what the NFL has done with their rules of parity. You can argue the owners were short-sighted, sure. But to make arguments about “capitalism” and business ethics seems ridiculous and off the mark.

And J.P. Morgan hardly was the person from whom they “cribbed” notes on eliminating competition. That’s been going on since cave tribes banded together to eliminate other rivals from their hunting grounds. To argue otherwise is disingenuous and further injects unnecessary political bias and distracting perspectives from what could otherwise have been a fine article.

I agree with your comments to a large extent, but there is some economic competition between teams that is foreclosed largely because of the antitrust exemption-the ability to move to new markets. For example, Peter Angelos was able to extort a sweetheart deal on the MASN TV contact to persuade him to “allow” the Expos to move to Washington. Similarly, the Giants have been able to prevent the A’s from building a stadium in San Jose by claiming it’s part of their territory. Under antitrust law, giving a competitor exclusive rights to a market would be known as market division and very likely illegal. The barriers to entry in baseball (and other sports) is, to some extent, an artifice constructed by the leagues to limit competition in particular markets. Now, obviously, a lot of baseball markets are natural monopolies, i.e., not large enough to support more than one team but if you look at the NY/NJ area, it’s quite possible that NJ could support a team but there is no way that the Yankees and Mets would allow that to happen. In other industries, firms are not allowed legally to keep other firms from breaking into the marketplace.

It is certainly true that, in most cases, the teams are not competing in an economic sense. Even where there are two teams in a market, I suspect there is little economic competition. The Yankees aren’t pricing their tickets based on concern that their fans will go to Mets games if the tickets are too high. There are very few fans, I think, that decide to go to Yankee or Met games depending on the relative price of tickets.

Not one word here about the expansion Senators, whose anonymous ineptitude (three straight 100-loss seasons, the last two in a new ballpark, D.C. Stadium) temporarily helped destroy baseball in Washington, losing a rapidly growing and affluent, increasingly multi-cultural metropolitan area for the rest of the 20th century; only the Nationals’ blossoming since 2012 has lessened the pain. And remember, this all happened in the shadow of 1960, when a young nucleus helped the original AL Senators to a strong second half and a fifth-place finish after being in the cellar for several seasons — but it would be Minnesota, not Washington, that would reap the benefits (in fact, the Twins clinched the 1965 penant at D.C. Stadium).

Didn’t MLB clean up its act with subsequent expansion drafts like in 1977 (for the AL) and in 93 and 98? I’ve always thought that it would make a great case study in expansion since Baseball has minor league teams to fill before they advance to the majors. I thought that in later drafts the new teams were already stocked in their minor league teams and were simply drafting unprotected players to protect their young prospects in their systems. Plus, Colorado in 1995, and Arizona in 1999 show that expansion teams aren’t relegated to joke status like the early 60’s Mets and 45’s were. Is there any material out these on these drafts since I can’t really find good source material on this.

I agree with the comments, but keep in mind that the Mets and Astros could have taken Richie Allen in the expansion draft and both teams passed.