The 1981 Split Season Still Speaks to Us

Fernando Valenzuela’s 1981 was one of the many great performances in that split season. (via Jim Accordino)

There are numerous approaches to writing about baseball. There are books that aim to analyze the game, from sabermetrically oriented approaches that explain the relationship between statistics, performance and value to new histories of race and integration in the game or baseball and labor. Then there are baseball narratives, from team histories and player biographies to single-season or multiple-season narratives. The problem remains though, that for each writer success with one style or approach does not guarantee success in the other.

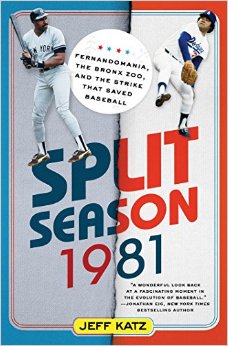

That said, the success and brilliance of Split Season: 1981, published last year, lies in Jeff Katz’s ability to combine the on-field action of the strike-shortened 1981 season with the labor struggle between players and the owners.

Fernandomania, the Bronx Zoo, and the Strike that Saved Baseball deftly interweaves the fraying negotiations between players and owners off the field and the on-field exploits of such players as Fernando Valenzuela, Rickey Henderson and Len Barker. When the season finally grinds to a halt, he follows the efforts not only of Marvin Miller, the executive director of the Major League Baseball Players Association, but of player representatives Doug DeCinces, Mark Belanger, Steve Rogers and Bob Boone. When play returns he follows the four through the end of the season and beyond.

Fernandomania, the Bronx Zoo, and the Strike that Saved Baseball deftly interweaves the fraying negotiations between players and owners off the field and the on-field exploits of such players as Fernando Valenzuela, Rickey Henderson and Len Barker. When the season finally grinds to a halt, he follows the efforts not only of Marvin Miller, the executive director of the Major League Baseball Players Association, but of player representatives Doug DeCinces, Mark Belanger, Steve Rogers and Bob Boone. When play returns he follows the four through the end of the season and beyond.

Another way to convey Katz’s storytelling skill is to note, because I’m too young to remember it, that the split season had always been to my mind a statistical anomaly or a turning-point in labor relations, but not really a season like I remember 1987 or 1989. However, by the end of the book, I cursed myself for caring whether the Dodgers or Yankees would win the World Series, I could feel how Reds fans or Cardinals fans might dismiss the results of 1981 with an asterisk or two, I felt indignation at the possibility that Boone was sold to, and DeCinces traded to, the Angels at the end of season as retribution for their efforts on behalf of the union. Finally, I grinned with pleasure when Katz notes that an Angels team packed with union leaders—DeCinces and Boone, but also Reggie Jackson, Don Baylor and Steve Renko—made it to the playoffs in 1982.

The role of strikes in sports, as Katz reminds us with ample evidence, is a contentious issue among fans. There is a prevalent view that strikes are caused by players’ greed and intransigence, and that free agency harms competitive balance. It has been voiced by owners, often echoed in the media , and then repeated by fans. I still hear this sentiment when my friends and I discuss the impeding expiration of the current collective bargaining agreement in December 2016. The key issue in 1981, which could be a key issue in future bargaining, is compensation for a team “losing” a free agent. In 1981, the owners implemented a system of direct compensation so that, as Katz summarizes

When a free agent was selected in the postseason reentry draft by eight or more clubs and ranked in the top half of performance in their position (pitchers measured by starts or relief appearances, hitters by plate appearances), then the team who signed the free agent could protect 15 to 18 players on their major league roster, depending on whether the free agent was in the top one-third or one-half of the rankings. The team that lost that free agent could then pluck a major league player from the remainder of the signing team’s roster. It was direct compensation, a punishment for teams signing a free agent.”

It was a plan devised to provoke a strike. If the players capitulated, as the owners mistakenly believed they would, they would be conceding important aspects of their free agency rights. Moreover, as Katz points out, the plan would penalize the free-spending ways of owners such as George Steinbrenner. Management, as Bowie Kuhn presented it in a speech at the annual winter meetings in December of 1980, viewed free agency as both a financial issue and a threat to competitive balance.

Katz ably shows that the owners’ appeal to competitive balance is secondary to their financial interests. He mentions the reporting of Murray Chass “or Leonard Koppett, who wrote detailed accounts on how competitive balance had been bettered with free agency and how roster turnover was nearly the same from 1979 to 1981 as it had been in the mid-1960s.” Then, in a passage that ironically evokes the so-called “Golden Era” of baseball, Katz writes:

The purported glory days were a false construct. From 1947 to 1958, the Yankees, Dodgers, and New York Giants won 18 of 24 pennants…. New York ruled and no one else had a chance. The complete absence of competitive balance was a hallmark of the time, the old way that the owners had wished to preserve when they fought to pull back on free agency.”

There is a persistent sentiment that sometime in the past baseball was more pure, that competition was stronger, and that players were more dedicated to the game. But, as astute historians of the game remind us, these nostalgic images of baseball past often obscure how the owners colluded to enforce various techniques of segregation and player exploitation. And, relevant to the present discussion, as Katz shows, the Golden Era was no more balanced than the period immediately following the emergence of free agency.

And yet, Katz notes, an “NBC poll showed 53 percent of those asked supported the owners in the strike, 47 percent the players.” Baseball, he continues, despite the “speed and intensity” of the major-league level, fosters the illusion that the Show is basically the same game that fans once played in Little League. Players, who would have made a minimum of $32,500 in 1981, appeared to be “spoiled brats” who earned significantly more money than the average American ($13,000 at the time) to play a game.

I am suspect of attempts to explain economic and labor struggles in moral terms, since our moral vocabulary is largely individualistic while these struggles are collective and concern baseball as a system. But there is a variant of this argument that reasons that baseball players make a disproportionate amount of money in relation to other forms of labor: there is something wrong with a system that pays athletes a ridiculous amount of money when we underpay other professions such as teachers, firefighters and nurses.

In either case, there seems to be a failure of political imagination around this issue at the outset of the Reagan era (though the strength and status of the players’ union vis-à-vis others’, such as the air traffic controllers’, is not lost on Katz). Why is this not an argument that workers in all industries ought to be paid more rather than that baseball players ought not complain about compensation? And where, exactly, do these critics of the players assume this money goes—which Katz pegs at over $8 billion in revenues today—if it doesn’t go to the players?

While I’m simplifying a bit on this point, Katz argues, as Marvin Miller did, that the owners and the commissioner have been successful in presenting themselves as the arbiters of what is in the best interests of baseball. It is a misperception that persists to this day. Kuhn worked to portray himself in public as a representative of both players and management, but his private papers demonstrate that he often equated the so-called best interests of baseball with the owners’ financial interests.

In the end, as we know, Kuhn’s misperception of his own role and the owners’ general misreading of the players’ solidarity contributed to Miller winning, in his words, the “complete and unconditional surrender” of the owners. The owners provoked the strike by implementing a system of direct compensation, and ended up negotiating a system in which teams could lose a player without signing a free agent. (This system was abolished in 1985). It was a give-back by the players, but one that was, as Gussie Busch of the Cardinals management saw, a Pyrrhic victory: “If the Cubs lose a player to the Phillies through free agency, then possibly I have the honor of giving the Cubs my twenty-seventh-best player—marvelous compensation.”

On the cover of its May 30, 1981 issue, The Sporting News published a cover with images of Miller, Kuhn and Ray Grebey (the owners’ negotiator) on a baseball diamond that asked: “Will They Kill Baseball… Or Save It?” As Katz sees it, the strike saved baseball. It solidified the free agent system that has made players “partners, in a very real sense, with management,” in which owners can no longer make unilateral decisions over the business of baseball or players’ salaries. In the long run, he argues, the vision of Marvin Miller has won out.

But, in a telling conclusion, Katz also notes that insofar as the “players association is every bit as interested in keeping the status quo as the owners,” Bowie Kuhn has won, too. While relative labor peace has prevailed in baseball for the past two decades, the next negotiations will open with Rob Manfred as commissioner rather than Bud Selig and Tony Clark the executive director of the MLBPA rather than Michael Weiner. Moreover, there have been suggestions of player discontent with the current qualifying offer system, and, most importantly, player salaries have declined relative to league revenues. As Nathaniel Grow writes:

After peaking at a little more than 56% in 2002, today MLB player salaries account for less than 40% of league revenues, a decline of nearly 33% in just 12 years. As a result, player payroll today accounts for just over 38% of MLB’s total revenues, a figure that just ten years ago would have been unimaginably low.

There is, then, a possibility that neither players nor owners can rely on the status quo in the upcoming CBA negotiations. Katz’s Split Season 1981 is a timely reminder of what could be at stake both on the field and off.

References & Resources

- Craig Calcaterra, NBC Hardball Talk, “A Reminder that Baseball’s Commissioner Works For the Owners”

- Nathaniel Grow, FanGraphs, “The MLBPA Has a Problem”

Are Major League players selfish? Of course they are; when was the last time they actually tried to increase the pay that minor league players make? But then again, so are the team owners. Baseball, like our entire economic system is built on the idea of maximizing profit. Thus, televised baseball has mostly moved to for pay cable channels… they black out streaming the home team… they even block radio streaming so you have to pay MLB if you want to listen to a game while you are out of town.

Ultimately, as we go forward with this, we need to keep in mind that the owners and the players both are not at all interested in how this spat will impact baseball fans other than how it will impact what goes into their wallets.

MLB players are part of a union, whereas MiLB players are not part of that union. Additionally, revenues are generated for the MLB product, not the MiLB product. How exactly do you see MLB players as selfish when they fail to think about what is essentially an unrelated workforce?

Unrelated workforce? The vast majority of Major League players get their professional start in the minor leagues. Most MLB players will spend time working with them in rehab assignments during their career. The reason we have minor league baseball affiliated with the major leagues is that the latter sees it as essential to keeping the MLB at a high standard of play. It also provides baseball to areas where attending Major League games is impractical due to distance. These are the reasons MLB teams play the salaries of minor league players.

Look, I am not talking about Major League baseball providing huge salaries for minor league players, these guys aren’t even being paid enough to afford a basic apartment and food. But really, would a minor league average of $30-40 K really hurt either the MLB players or the owners that much?

Fans have always favored the owners over players and, in general, always favor business over labor because strikes take away something that people want or need. And baseball players, even during the Reserve Clause era, have always made more than most American workers. People resent that ballplayers make more than, say, teachers, but in a market economy, the market allocate resources in a way that is often not socially desirable. You either accept that or you move to a different kind of economic system. IMO, you need to place limitations on the market to prevent externalities and other market dysfunctions. Unions, along with government regulation, arose to address the disparities of power between business and workers who, in many cases, were essentially fungible However, in terms of allocation within a private business, such as baseball, where the players are not fungible, I think the market should decide who gets paid what. Thus, I think players should be free to get as much as they can, as other professions are in America, but I don’t think they necessarily deserve a specific portion of the revenues. In sports with salary caps, that kind of formula makes sense but, in baseball, the fact that the players’ overall share of revenues is decreasing doesn’t bother me that much, as long as it is based on market forces. (Recognizing that there really is no such thing as a “free market.”) There are certainly areas that the players’ union needs to address to make the baseball market function more efficiently, i.e., the free agent draft compensation system clearly hurts the free agent market. But, should the players’ automatically be entitled to a share of internet revenues and the like? It seems to me that the market allocates that in the way that free agents are paid and, if you address problems with free agency, the players will eventually get a larger share of the pie. I mean, who is to say whether the players are “entitled” to 30% or 60% of total revenues?

12 years old in 1981, from Brooklyn and was supposed to go to the game for my birthday, the first day of the player’s strike. Together, that’s why Arvin Miller will be right next to Walter O’Malley in Hades. As I’ve gotten older, I realize Bowie Kuhn should be right there with them as well.

Why is Marvin Miller there? The players were right. Saying a pox on both you houses is silly. It’s like blaming the Allies and the Nazis equally for WW II. You aren’t 12 anymore.

Minor league players that never make the majors live off signing money, if they were drafted high enough. Their salaries are determined by their performances in high school and college, which is much less predictive of their value to the major league team than their minor league performance. That doesn’t look to be perfectly in the interest of the owners and the major league players either.

A friend who played college baseball called MLB players “genetic freaks.” Dallas Braden on yesterday’s Baseball Tonight program spoke of a conversation he had with his grandmother about the “generationl wealth” these genetic freaks earn, saying they earn enough that their GRANDCHILDREN will never have to work. They CHEAT, using whatever substance can be ingesedt to earn that wealth, yet “fanatics” continue to support their cheating by whatever means possible.

A recent article in Forbes headlines, “The Braves Play Taxpayers Better Than They Play Baseball.” MLB has bilked taxpayers for decades. This will end in future, come the revolution.

The players can complain that they get too little of the money that the owners and MLB executives get. But they are still getting paid very well. The group that is getting screwed is the fans. In an ideal universe the management of a pro sports franchise should have a contract with the fans to give priority to on-the-field performance and availability (no blackouts) at a reasonable price. Instead ownership maximizes its profits by bilking the taxpayers for stadiums, high ticket prices, and not always the best performance. Sometimes a team can produce a better profit picture by low profile and mediocre performance. The NFL is much worse than MLB in the floating crap game of movable franchises, but the threat exists when the economics are bad enough. It is not the fault of the fan/taxpayers who pony up for a stadium and then get bad performance followed by the team deserting them for another city of suckers who build a stadium. The alternative is the Green Bay Packers community ownership model. The GB model shows how a team can contend and receive major league support from essentially a minor league economic base. The labor organizing of the players’ union would be nothing compared to a consumer revolution. There should be community groups buying out the ownership backed by the threat of a consumer boycott. Go watch baseball in the independent leagues, small college and high schools, where they get closer to playing for the love of the game and where you can get closer to the field and invite the players for dinner at your house. Otherwise you might as well just play a computer baseball game.

Can we agree that all sides and even more specifically each individual is arguing from wherever they happen to be situated by individual greed?

In a sense, the players are arguing for a greater number of similarly situated people, since there are more players than owners. The difference is the owners have more capital which equals power. Both sides are leveraging the power they have to maximize what they can get out of the other side. As in many labor situations, lower status employees are sacrificed for the higher paid positions (like part-time workers rights and benefits are sacrificed in parts for concessions from management to not cut this or that in labor negotiations) which addresses why MLB players aren’t bargaining for a higher wage floor for minor leaguers and better protections or allowances for being shipped to 4 places in one year with all the drain in living expenses associated with it. This is mainly because owners want the MLB level players to take a haircut in some fashion in exchange. Hopefully minor leaguers can successfully unionize themselves and use the leverage of growing leagues in other countries to at least get somewhere.

It’s sausage making at its ugliest except for state and national politics and the government contract landscape, lobbyists, etc.

There are no human villains, only a system with some perverse incentives. Fix the head of the snake (as in brain surgery) and it’ll slither better. Change the system from one where every individual is for the most part out for themselves and the sausage making becomes more pleasant to look at.

It’s our conscience that is repulsed at greed that makes us uncomfortable, not the evil of any of the humans involved.

A few things I’d like to address in that.

The MLB players union main abandonment of minor leaguers is not bargaining to incorporate them within the players union, which you missed. But otherwise I’m in agreement with that.

In addition, the minor league players would more specifically be leveraging the increasing amounts of playing opportunities in other countries where demand and the markets are growing. The specter of leached off talent where American players choosing to opt permanently to play in smaller ponds could become significant enough where it affects the talent level in the product of the United States, especially given the static nature of 30 teams 26 man active and 40 man rosters. MLB owners can attempt to limit this by expanding nationally, expanding internationally through trying to buy up and Americanize (own) the foreign markets as much as they are allowed, or at the very least greater cooperation (or collusion) between the existing foreign leagues and the U.S.

It will be interesting to see if the Cuban love of Baseball will lower their values against what they judge the ugliness of capitalism to allow the MLB to bring a team there that competes within the U.S. league given the close proximity or at least an All-Star Cuban Nacionale team versus U.S. All- Stars. Something a bit more involved than what they are doing in Australia. Players (Zach Greinke) will probably be much more amenable to that.

Anyways Satchel, hope I added a bit to your observations.

That’s 2011’s Game of the Year, banned from the Windows Store. How about 2012? With several highly anticipated games yet to be released, it’s anybody’s guess which game will be selected. But a random sampling of internet predictions suggests some of the leading contenders are Max Payne 3, The Witcher 2, Mass Effect 3, Assassins Creed 3, Call of Duty: Black Ops 2, and Borderlands 2. Of the four of those that have already shipped and been rated by PEGI, how many could be shipped on Windows Store? Adobe Audition CS6 Social Print Studio is our beloved photo printing company, we’ve been around for 6 years now and have been profitable since day 1.

Hate the kickstand on the Surface Pro 3 when I put it on my lap, meaning it’s a no-co from an ergonomic standpoint. There, clamshell still wins. Adobe Illustrator CC Each of your friends must send this to at least 5 people or you won’t be eligible, so choose your friends wisely!