The Cy Young That Never Was

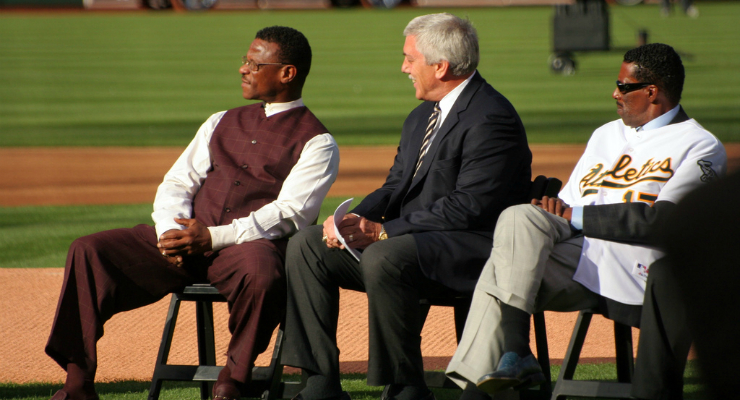

Mike Norris, right, was robbed of the AL Cy Young award in 1980. (via John Morgan)

Two years ago, when the Oakland Athletics found themselves in the thick of a momentous September surge that would culminate in clinching the AL West on the final day of the season, I found myself in a grocery store adjacent to my Oakland neighborhood. I was headed to the A’s game that day and had stopped to pick up various supplies on my way to the stadium. Standing behind an older man in line who noticed my A’s hat, he and I started talking about the team. We discussed the trajectory of the season, whether we could win the division, how our starters and bullpen were pitching really well down the stretch -– normal baseball fan topics –- until he brought his wallet out to pay the cashier.

“Want to see something?” he asked me, after handing a twenty to the cashier.

From his wallet, he pulled out a baseball card and offered it to me. It was well-worn: the cardboard had grown soft, the edges were folded and ragged, and the front was faded, like a film shot in Technicolor decades ago that was put on a warehouse shelf and forgotten about.

I could still read the name, despite the discoloration.

“Mike Norris.” I read off the card. “Is that you?”

“It is.” He said.

I compared the skinny guy with the pencil-thin mustache on the card to the man standing in front of me. The resemblance was there, but he didn’t look like a former major league pitcher — or what I thought a former major league pitcher should look like. He wasn’t extremely tall, didn’t have a particularly stocky build, and his arms were a pretty normal size, maybe a little long.

In the moment, I didn’t think to ask him why he was carrying a baseball card of himself around to show to strangers. I didn’t think to ask him why he was on permanent crutches, or why he was in the store, or what had transpired in the 31 years between the frozen photo of him mid-windup on the 1981 Topps in my hand and the September day in 2012.

I didn’t think to ask him anything, because I had flipped the card over and seen the line of his 1980 season.

The numbers: 22 wins, 284.1 innings pitched, 180 strikeouts, 2.53 ERA, 1.04 WHIP.

Twenty-four complete games.

It was a dream year: the kind that only comes when a young, lanky right-hander with first-round talent has the epiphany -– the click -– and is almost unhittable from then on.

“Holy ****,” I said.

Later that day, after the game, I rushed home to look up his 1980 season in depth, a season that kept getting better and better as I pored over the statistics. By traditional measurements, his season was exemplary; by sabermetrics, it was better. Among his American League pitchers, he ranked:

- third in Fielding Independent Pitching

- first in Adjusted Pitching Runs

- first in Adjusted Pitching Wins

- first in pitching Wins Above Replacement

However, there was one number that stuck out on his Baseball-Reference profile page more than any other: a CYA-2 under the “Awards” section. Clicking on the link, I saw the 1980 AL Cy Young voting for the first time, and Mike Norris’ words from earlier in the day echoed in my head.

“They robbed me,” he had said to me, taking the card back to look over it, as if there was something he had missed in the 30 years it had been in his wallet. “I should’ve won the Cy Young.”

It was a very close vote. Steve Stone, starter for the Baltimore Orioles and winner of 25 games, tied with Norris with 13 first-place votes. The voters who didn’t vote for Norris to win put him further down the ballot (Stone received 10 second-place votes to Norris’ seven), which gave him a smaller share of the overall points and handed the award to Stone. Three voters left Norris off the ballot completely.

The race wasn’t close, however. The 1980 campaign was not a case of this year’s AL Cy Young race between Felix Hernandez and Corey Kluber, in which both pitcher’s statistics are separated by razor-thin margins. Norris had trampled Stone in every pitching category during 1980, except two: wins and winning percentage. Stone played for a team that won 100 games; Norris played for a team that won 83. As a result, Stone went 25-7 and Norris went 22-9. Those were seemingly the only statistics the voters paid attention to.

Over the course of the two years since I met Norris in that Oakland grocery store, I haven’t been able to stop going back to the 1980 AL Cy Young. What happened to Norris after 1980? More importantly, why hadn’t I heard more about him, the victim of one of the greatest Cy Young snubs in history?

…

I started at the beginning.

Mike Norris was drafted with the 24th pick in the first round of the 1973 amateur draft by the Oakland Athletics out of the City College of San Francisco. His first start for the A’s major league club came in 1975, and for the next four years he had relatively little success, posting a career 12-25 record with a 4.67 ERA and 1.53 WHIP after the conclusion of the 1979 season.

Many of the losses Norris suffered can be attributed to the performance of the team, which, after winning three straight World Series from 1972-74, went through a serious rebuilding stage as Norris came up through the ranks. After winning 98 games in 1975 before bowing out to the Royals in the ALCS, Oakland lost 74 games in 1976, 98 in 1977, 93 in 1978, and 108 in 1979.

Something changed in 1980 for both the A’s and Norris, when the starting rotation was filled with young aces under new manager Billy Martin: Rick Langford won 19 games with a 3.26 ERA (along with 28 complete games), Matt Keough won 16 with a 2.92 ERA (20 complete games), and Norris emerged as the best of them all. Steve McCatty and Brian Kingman rounded out the rotation, each logging more than 210 innings and sub-4.00 ERAs.

Under Martin, the first three starters threw a combined 824.1 innings in 1980, making them the last team with three starters to throw at least 250 innings each with an ERA under 3.30. The heavy workload of the starters would come to form part of Martin’s managing style, colloquially known as “Billyball,” and was the suspected cause of all five of the starters in the 1980 rotation having their careers cut short through injury in the ensuing years.

As Norris would tell the L.A. Times in 2011 regarding Billy Martin mound visits,

“If you told him you were tired, he would look at you like you were less of a man,” Norris said. “So I told him to get the hell out of there.”

And, more often than not, Martin got the hell out of there. The young right-handed Norris would pitch 284.1 innings in his marquee 1980 season, second-most in the American League. The highlight of the season, for those inclined to grueling and painful marathons of athletic prowess, was a 14-inning game against the Jim Palmer-led Orioles. Norris went the distance, giving up 12 hits, two walks, and two earned runs, facing 51 batters along the way. He finally got the win after Tony Armas hit a walk-off grand slam in the bottom of the 14th.

By the end of the season, Cy Young buzz was following the new ace of the staff. Following his final start of 1980, an 11-3 win over Tony LaRussa’s White Sox in which Norris pitched his fifth straight complete game, LaRussa would say, “The guy that beat us today has got to be the leading candidate for the Cy Young.” Martin went further after the win, saying “…if they can’t make their decision based on what he’s done by now, they’ll never do it.”

The right-hander would finish the season with remarkable achievements: out of the 33 starts he made, 24 were complete games, including five extra-inning complete games of 11, 14, 10, 11, and 11 innings. He posted a career-best 7.3 percent walk rate, won his first of two Gold Gloves (the only A’s pitcher ever to win the award), and finished in the top three in the AL in WHIP, hits per nine innings pitched, innings pitched, strikeouts, wins, and Fielding Independent Pitching.

With statistics alone, Norris seemed to be a lock for the Cy Young. Stone finished outside the junior circuit’s top five in most of the categories above (WHIP, H/9, IP, Ks, & FIP); in some cases, he didn’t crack the top 10 (WHIP, FIP). There seemed to be a clear winner by the end of the season. As Norris would say in September of 1980, “…based on my stats, there’s no question I’ve done a better job than he has.”

Norris didn’t win the Cy, however. Three voters would go so far as to leave him off the ballot completely (there were three spots on the ballot from 1970 to 2010). Those members of the BBWAA were from Kansas City, Detroit, and Anaheim. Norris went a combined 5-1 with a 1.41 ERA and 0.92 WHIP against the Royals, Tigers, and Angels in 1980.

It’s no secret that wins and winning percentage bias dominated the Cy Young selection process up until very recently, but what were the other reasons the award was given to Stone instead of Norris?

There was the possibility of a Baltimore/East Coast bias. Starting in 1973, Orioles pitchers won four out of the next seven Cy Young awards: Jim Palmer in 1973, 1975, and 1976, along with Mike Flanagan in 1979. Voters could have factored organizational pedigree into their ballots, as Baltimore was a highly successful franchise during the 1970s. Stone also started the All-Star Game for the AL, pitching three perfect innings, and the Orioles were AL favorites from the very start of the season. Stone was also at the tail end of his career, with Norris just starting to hit stride.

As Norris would say following the Cy Young decision, “I guess that they thought Steve was the most deserving. I can accept that … I have a lot of years ahead of me. I hope I can be considered another year.”

…

There wouldn’t be another year like 1980 for Norris.

With the heavy workload under Martin, it is unsurprising that all five of Oakland’s 1980 starters would flame out with a variety of elbow and shoulder issues in the ensuing seasons. Langford had only two more successful seasons before being released in 1985, Keough would never again surpass 100 innings pitched during a season after 1982, McCatty was done by age 31, and Kingman was finished after 1982.

For Norris, there was the confluence of two separate but equally damaging influences on his career following his breakout season: the emergence of nerve damage in his throwing shoulder and the rampant cocaine epidemic that plagued baseball in the early 1980s. 1981 provided a strike-interrupted season with ample downtime for extracurricular activities and a loss of shoulder strength, followed by a 1982 season that saw the introduction of “Billyball” into all levels of the Athletics organization after Martin was given the reigns of baseball operations in Oakland.

In 1982, younger pitchers were throwing complete games in place of the major league starters during spring training games, leading to a lack of preparation for the grueling nine-inning contests that would await them starting Opening Day. Norris hit the DL with shoulder tendinitis in June of 1982 just as the rest of the staff wilted under the intense workload, and he had surgery on his balky shoulder in November of 1983 after pain and ineffectiveness had mounted. His injury also heightened his dependence on drugs, propelling him out of the league and into drug rehabilitation. He would make a short comeback in 1990 for the A’s and pitch well, but he was released following only 27 innings of work.

…

Two years after our chance meeting in the store, I decided it was time to ask Norris about his career, the Cy Young race in 1980, and his current life. During my month-long search for him, I found a few surprises, countless stories about legends and Hall Of Famers, and a program for at-risk youth that uses baseball as a tool for social mobility and healthy habits.

With a quick search, I found out the former ace now heads a program called the Mike Norris School for Baseball and Wellness, a partnership with a non-profit in the Bay Area that seeks to engage urban youth through a curriculum of baseball and proper diet/exercise. The program is in the early stages of its partnership with the non-profit Peacemakers, Inc., but it serves as an after-school program to help keep children from some of the negative repercussions of living in low-income urban areas.

From there, I called numbers that turned out to be disconnected, sent emails to addresses that never responded, and called the non-profit and left a message. A few days later, I got a bite, speaking with the founder, Hank Roberts. He laid out some of the great mentoring work the organization is doing in Oakland and surrounding counties. He said he would put me in touch with Mike.

A few minutes later, I got a call.

“This is Mike Norris.”

Two days later, I’m sitting across from him in a café in Oakland. He is taller than I remember. His hands are huge. He has the easy smile and affable way about him of someone who has been interviewed a thousand times.

He looks, in his very essence, like a major league pitcher.

For the next three hours, we speak intently: about him first getting to the minors, about the grip of his screwball, about getting charged by Dave Winfield after a brush back. He tells me about a 19-year-old Rickey Henderson and a discussion with Bob Gibson. We discuss at length his School of Baseball and Wellness, an engaging program for the youth of Oakland. When we part ways, we make a plan to meet again.

After I leave the café, I walk home and sit down at my desk. I pull out my tape recorder, see I have three hours of stories, and press the play button.

I just went nine, but I’m coming out to pitch the tenth. This thing is only getting started.

…

References & Resources

- Special thanks to Graham Womack at baseballpastandpresent.com for help with archival newspaper research.

- Associated Press. “LaRussa, Martin cite Norris for Cy Young.” The Pantagraph, 2 Oct. 1980: p. B-5.

- Associated Press. “Mike Norris is Thinking About Cy Young.” Santa Cruz Sentinel, 11 Sept. 1980: p. 33., Web. 13 Oct. 2014.

- Associated Press. “Stone Receives Cy Young Award.” The Cornell Daily Sun, 13 Nov. 1980: p. 1.

- Ben Bolch. “In 1980 & ’81, Oakland A’s pitchers had the finishing touch.” Los Angeles Times, 18 Jul. 2011: n. pag.

- Jeff Kallman. “The Rise and Demise of the Five Aces.” Throneberry Fields Forever. Throneberry Fields Forever, 22 Feb. 2012.

- Ron Kroichick. “He’s finding his control.” San Francisco Chronicle, 25 Jan. 2004: n. pag.

- David Nathan. “1980 Cy Young Race Revisited.” Seamheads.com. The Baseball Gauge, 19 Mar. 2011.

- Sports Reference LLC. “Mike Norris Statistics and History.” & “Pitching Season Finder.” Baseball-Reference.com, Major League Statistics and Information.

- Mike Tully. “Orioles’ Stone AL Cy Young Winner.” Tyrone Daily Herald, 12 Nov. 1980: p. 15.

Great article, Owen. Even as a kid in Detroit, I remember the “Billy-Ball” teams well. One correction: the A’s lost to the Red Sox in the ’75 ALCS, not the Royals.

love this. even as a lifelong A’s fan, I’ve never fully appreciated what Norris accomplished in 1980. It’s a shame that his career was shortened so dramatically, but great to her about his current work and focus.

Keep it coming

East Coast bias? I can buy into that. Does anybody seriously believe that Jim Palmer was more deserving of the Cy Young than Mark Fidrych in 1976?

There might have been a bias of different kind going on there.

Great Article. I attended the 14 inning affair in 1980 where Jim Palmer last I believe into the 8th inning but Mike Norris went the distance. Professional baseball players take on a larger than life appearance to the next generation watching them. Whether it is deserved or not, Mike Norris’ “cat like” ability off of the mound coupled with his screwball made him one of the most unique pitchers of the early 80’s. His career can be looked upon as an underachievement but that would not be a fair assessment. His career along with the rest of the ” 5 Aces” that comprised that A’s pitching staff is more an indictment on Billy Martin and Art Fowler’s disregard for the long term effects of their pitching staff by not limiting their innings. Mike Norris had an indelible effect on Oakland native Dave Stewart. Hopefully, he shared in Stewart’s success in the late 80’s. Lastly, let’s not forget Charles O. Finley’s eye for talent by drafting him. Had Norris stayed healthy, his career could have been potentially Hall of Fame worthy.

Martin was one of the most effective managers I’ve seen over the years, but also damaging. He was mercurial both in temperament and his managing style. While you wonder what happened to cause Mike Norris to miss out on the Cy Young Award, I look back and wonder what happened to that great young pitching staff. The answer is Martin. He secured greatness from them in the short term, but damaged them in the long run. Nothing new. When he took over the Yankees midway through 1975, he pushed Catfish Hunter as hard as any pitcher I’ve seen, unnecessarily for a mediocre team that was long out of it, yet Hunter went on to have the first 300 IP/30 complete game season in decades, since Bob Feller. Hunter was a workhorse, but he was fatigued as the season went deep, and those are the conditions when arm injuries occur. He showed up the following Spring Training with a slightly sore arm and some decreased velocity. He still went out and pitched another 300 innings. He was never the same, a fate suffered by many of those young A’s pitchers.

It’s not just more wins, it’s 25 wins. That doesn’t happen often. You’ll win the Cy Young if you win 25, unless you’re Juan Marichal.

To Mr. Punch. Add Mickey Lolich to that list. 25-14 in 1971. Vida Blue wins the Cy. And honorable mention goes to Wilbur Wood for winning 24 games in 72 and 73 and no Cy. Granted, he lost 17 and 20 in those years so that makes his wins less impressive.

Just wondering if he explained the significance of the two dimes he carried in the back pocket of his uniform. I remember when he first came up, pitched a gem, maybe vs. the Chisox, then was hurt in his next start and so began the wait and see process that lasted from ’76 – ’80.

The dimes were his talisman to try to get to twenty wins.

Thanks for the great article, Billy overshadowed so many on that team, and so much was made of all those complete games, especially by Langford.

Great article, Owen. Look forward to reading more.

Morris certainly should have won the Cy Young that year.

Re everyone’s comments on Billy Martin.

Take a look at the innings Catfish Hunter and Vida Blue pitched under Dick Williams.

Look at Dave McNally and Jim Palmer’s numbers under Earl Weaver.

It wasn’t just Martin.

These were top notch managers in the days before pitch counts and when the DH was still less than a decade old.

You are certainly correct about that. Mickey Lolich threw 376 innings in 1971-also I believe under Billy Martin.

Also if I remember correctly, didnt Norris have some sort of arm trouble or injury in 1976?

He came up at the end of the 75 and mgr Al Dark called him “Jeremiah” but I don’t remember the quote he used, something like when we were in trouble, Jeremiah came. I think he threw a shutout and had a couple of other effective outings, something like the 1970 appearance of Vida Blue that made people expect something big in 1976. Instead, he got hurt and would pop up and down like many busted prospects except he put it all together for a brief stretch.

I haven’t read the Mudcat Grant boot “Black Aces” but I would expect Norris is one of the featured players.

As great as Norris was during his salad days, and as durable as he was, he was slow to warm up starting the game. If you were going to get to him, it would have to be in the first inning.

I appreciate a good read like anyone else. But, most importantly, I think you captured a ‘real’ story about a ‘real’ man who contributed to the Oakland A’s and the life and times of baseball. Unsung stories are most compelling whenever you revive untold stories. I look forward to reading more about Mike Norris and updates on his current work and what happens when someone is actually ‘robbed’ of the Cy Young award; and if Mr. Norris would have won, would life be different for him….or not? I anxiously await the next article.

Anybody have any idea who the three writers were who left him off the ballot? Seems as if they’ve got some ‘splaining to do.

Good article, and I look forward to more. Billy Martin was also working a mini-miracle with Tony Armas, who wasn’t very good before Martin became the A’s manager. Norris was great and his 1980 Strat card reflected that. Anytime I rolled against that card he did the job, with lots of complete games.

Great article. Norris was one of my favorites during the BillyBall period, and I remember being puzzled by his release in 1990 when he came back and pitched pretty well. I guess they wanted to go with younger guys like Todd Burns and Reggie Harris.

But I doubt his WHIP was listed on a 1980 baseball card, as the stat was only invented in 1979, and didn’t come into common use until much later.

Well written, other than the gaffe about losing to the Royals, since they were in the same division back then. Mike Norris was one of my favorite all time A’s. My uncle lived in Mill Valley and regularly went to see them play, rather than brave the cold Giants games at Candlestick. I remember getting a Mike Norris autographed ball from him for my birthday, probably around 79 or 80. I always thought that he got robbed that year, too.

@MikeD “When he took over the Yankees midway through 1975, he pushed Catfish Hunter as hard as any pitcher I’ve seen, unnecessarily for a mediocre team that was long out of it, yet Hunter went on to have the first 300 IP/30 complete game season in decades, since Bob Feller.”

Being a Red Sox fan, I remember 1975 well.

Were the Yankees certainly not “long out of it” when Billy Martin took over for the fired Bill Virdon on August 1st? That’s a matter of perspective and history. Boston was playing .600 ball; the Yankees near the .505 clip and 10 GB the Sox, one game behind the Orioles.

The previous year on August 1st, division leading Boston was playing .544 ball and the Yankees (.490) sat in 5th place 5.5 games behind. When the season ended, it was Baltimore that sat on top of the A.L. East, the Yankees two games out and the Sox five more behind New York. In other words, in the final two months of the season Boston and New York headed in opposition directions and exchanged 10.5 games in the standings between them.

So why would any manager worth his salt, let alone one managing the Yankees under George Steinbrenner – let alone Billy Martin of all people – throw in the towel with two months to go and 10 games to make up one season after that?

That’s the way the game was played before the free agency era (exempting Hunter’s unique status in that regard). Injuries were viewed as part of the game, with little regards to the team’s long-term outlook five to eight seasons down the road and surely without worrying about insuring today’s $200 million contracts.

Ralph Houk’s Tigers were 11 out and in 5th place behind Boston. Yet Mickey Lolich completed seven of his 10 last starts, throwing 78 innings and facing 346 batters.

Chuck Tanner’s White Sox were 15 games behind Oakland heading into August. Yet he sent 33-year old Wilbur Wood out for 15 more starts in the next 55 days. Did it matter that Wood was headed towards a 291 inning season coming on the heels of those with 334, 376, 359 and 320?

Heading into August 1st, 1975, the Dodgers were 14.5 behind Cincinnati. Yet future Hall of Fame Walter Alston still had Andy Messersmith pitch at least eight full innings in nine of his remaining 13 starts, facing 405 batters – this in the National League and without the DH rule! Messersmith finished the year with 19 complete games, 40 starts and 321 2/3 innings pitched – all league-leading categories for a defending pennant-winner that would finish 20 games out.

As for Yankees, Catfish had already thrown 18 complete games in 25 starts, facing 826 batters in 218 innings with Virdon in charge before Martin even took over.

Yankees owner George Steinbrenner hired Martin to get the Yankees out of out their decade-long doldrums, not to worry about a pitcher’s arm – not even perhaps the best in baseball at the time.

While much is often said about Martin allegedly ‘ruining’ Hunter’s arm, little is said that Hunter had just gone six consecutive season prior to 1975 in Oakland in which he pitched anywhere between 247 and 318 innings, faced between 1002 and 1240 batters in between 35 to 40 starts a season under John McNamara (1970), Dick Williams (1971-1973) and Al Dark (1974).

The A’s won four straight division titles with Hunter and he won three straight World Series rings – not to mention a then-record $3.25 million dollar contract (that included a $1 million signing bonus) due to the ineptitude of Oakland owner Charlie Finley.

New York needed Hunter to replace Mel Stottlemyre, who had suffered a rotator-cuff injury in 1974 and retired after going nine consecutive seasons in which in pitched between 251-291 innings and faced between 1042 and 1244 batters.

As part of the Yankees, Hunter led a staff that won three straight pennants and he collected two more championship rings. For Catfish, that was five World Series rings, six pennants and seven division titles in a eight year span.

In fact, if it weren’t for Catfish Hunter, Billy Martin might not have become the Yankees manager in 1975 at all.

On May 1st at Shea Stadium, Hunter shutout the Orioles and Jim Palmer, 5-0. New York then lost six straight until Hunter shutout the Athletics and old (and future) team Ken Holtzman, 3-0.

Two more losses for Yankees followed until four days later Hunter pitched a complete, 10-inning, 4-3 win over the Angels in Anaheim. New York flew back home and promptly dropped two to Oakland before, yes, Hunter again got them a win, 9-1.

It was now May 18th and the Yankees stood at 13-20, 6.5 games behind division-leading Milwaukee and in last place in the AL East and Hunter was largely responsible for the only four wins the Yankees had during a 14-game stretch.

To think that Bill Virdon, or anyone for that matter, would survive as manager of the Yankees had they suffered a 14-game losing streak under owner George Steinbrenner boggles the mind. So it’s no wonder that Virdon would rely on Hunter again and again. In fact, Hunter would pitch at least 8 innings in his next 13 starts – that in a 32-day span. So if anyone “ruined” Hunter’s arm in 1975, the finger should be pointed at Virdon – not Martin. He had Hunter pitch on only three days rest 15 times through the end of July.

When Hunter was struggling in 1977, Steinbrenner told the New York Daily News: “”If Catfish never pitches another inning for us, as far as I’m concerned he was worth every penny. He brought a winning attitude to this team, and he can spend the rest of his contract sitting on the bench in a tuxedo, smoking a cigar, and I’ll be happy to pay him.”

Just to clarify why Martin wouldn’t have became the Yankees skipper in 1975 had Virdon been fired in May.

Martin was still managing Texas at the time. When Virdon wax fired in July, Martin had just been fired by Texas.

If Virdon is shown the door earlier, Steinbrenner has to get someone else. He still wanted Dick Williams who was then managing the Angels. Yogi Berra hadnt been fired by the Mets yet but the Boss really didnt even want Martin later hiring Berra as a coach.

One possibility might have been Leo Durocher, perhaps as a caretaker until Williams became available.