The effect of seeing pitches

With the World Series in full swing, there has been ample opportunity to analyze in great depth the decisions of the two managers. A popular topic has been the reluctance to pull starting pitchers as they are set to face the opposing lineup for the third time, with well-rested relievers waiting in the pen. I have written before about the typical approach and success rate for pitchers across times through the lineup, and MGL has most recently highlighted the relative penalty expected for starters as the game progresses regardless of the pitcher’s performance to that point in the game.

While we know that each time a pitcher and hitter square off in a game, the hitter gains more of an advantage, can we see this at a more granular level? To do so, I have used PITCHf/x data from the past three seasons and broken down batter performance based on the number of pitches seen from the same pitcher in a given game. Does offensive performance improve on each additional pitch seen by a hitter?

In addition, while I could believe seeing any offerings from a pitcher could help a hitter pick up timing and release point information, it seems to me that a hitter might gain at least part of this advantage through seeing a particular pitch type multiple times. In other words, if someone threw me four pitches to look at and asked me to hit the fifth (aside from the fact that I could not touch any big league offerings) I would have a much better chance of hitting the fifth if all five pitches were fastballs than if I got to watch four fastballs and then was thrown a curveball. I would have no prior experience in this game with the kind of velocity and movement that accompanies a curveball, so the first time I see it would be baffling.

This is actually what I wanted to examine the most in this study—the typical improvement experienced by batters for every instance of a given type of pitch that they are thrown by a given pitcher in a game.

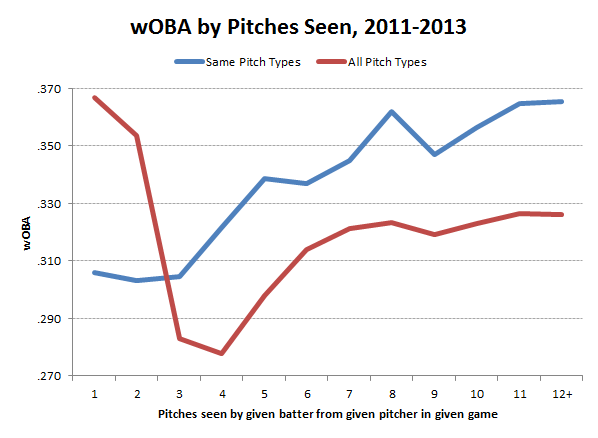

To start, consider the following graph showing the weighted on base average (wOBA) of hitters per pitch seen as well as per pitch of the same type faced from the same pitcher in the same game. In this case I have collapsed all pitch types as classified by MLBAM into an “average pitch” to determine first if a trend is visible.

From the graph (which is zoomed in so presents a non-zero starting point for the y-axis!), it is clear that hitters are building on their levels of success upon each occasion that they face a particular type of pitch from a pitcher within the same game. Also presented is the wOBA based on all pitches seen, which shows a steep decline until the third and fourth pitches before also following a rising pattern. I have seen this pattern exposed previously, with one example being David W. Smith’s work. The decline is really just a result of batters not being able to strike out until at least the third overall pitch that they see, so by definition any plate appearances that end within the first two pitches are at the whims of BABIP (or else a home run or a hit by pitch). Taking all strikeouts out of a set of possible outcomes clearly drives expected offensive output in a positive direction.

So we now know that in general, hitters improve their fortunes every time they face a given type of pitch from a particular pitcher in a game. The next question is, which pitches tend to hold up the best over the course of a game, and which fare the worst? I split the study by MLBAM pitch type, and calculated the typical increase in wOBA per additional pitch thrown again.

| Pitch | wOBA Delta/Pitch | Samples |

|---|---|---|

| Curve | .009 | 47420 |

| Slider | .006 | 89731 |

| Change | .006 | 60961 |

| Sinker | .004 | 49064 |

| Cutter | .003 | 29415 |

| Two-seamer | .003 | 68489 |

| Four-seamer | .002 | 186794 |

wOBA increase per pitch to given hitter from given pitcher in given game, by pitch type (2011-2013)

I can make a few observations about these results. The first is that in general, breaking balls and offspeed pitches decay at a faster rate than fastballs. Overall, “soft” pitches as a group show an average .006 wOBA increase per pitch to the same hitter, while “hard” pitches as a group typically inflate wOBA by .003 per pitch. This two-to-one ratio lines up with standard pitch usage, which over the past three seasons has been 64 percent “hard” and 36 percent “soft.”

The results also speak to the reason that starting pitchers typically need to have a more varied repertoire than relievers. Facing the same hitters three or even four times in the same game, starters must routinely throw a dozen or more pitches to the same batter. A more diverse arsenal allows a starting pitcher to architect pitch selection to keep the number of instances of each pitch type lower than if he had only two pitches to mix, lowering the expected wOBA- against. In effect, varying pitch types allows a pitcher to move along the lower red wOBA-against line in the graph above as they face hitters multiple times rather than the blue wOBA against line if they were forced to throw a solitary pitch type again and again.

The curveball that baffled me in my example above appears to be the type of pitch that professional hitters adjust to the quickest, outpacing the other secondary offerings. While not included in the table due to small sample sizes, both the knuckle-curveball and knuckleball demonstrated the best performance over repeated use, with each of them posting negative wOBA trends over the first several instances within a game. The knuckleball, of course, is an extreme outlier pitch type, as it tends to be a pitch that a hitter would see none of in nearly every game and then practically nothing but when facing a knuckleballer.

One final point: while I have published the expected wOBA steps per pitch above, each pitch type has its own initial wOBA-against for the first time it is thrown. Although breaking and offspeed pitches rate poorly in terms of rapid loss of performance per instance used to a given hitter, they still in general fare much better than fastballs in absolute terms. There are likely many reasons for this, including the fact that pitchers will tend to turn to their fastballs when in hitters’ counts to get one over but offer up a secondary pitch out of the zone when ahead in the count.

The times through the order penalty realized by starting pitchers is real. Now we can see that each additional pitch makes things generally worse for pitchers, so managers get your bullpens warming early!

References & Resources

Credit and thanks to Baseball Heat Maps for making available the PITCHf/x database upon which this analysis is based.

Nice work, I was going to look at something very similar, does the number of pitches a batter sees in his first PA, effect his second PA, which you have gracefully answered.

Thanks Jeff.

Interestingly, I had started by looking at the *exact* same problem as you described, and then expanded it to cover a more general situation.

I was still thinking of writing about it, but maybe it isn’t worth it any more. Basically, because of that trough 3-4 pitches in, first PA pitches seen don’t appear to directly influence second PA performance.

However, when I looked at the number of *unique* pitch types seen in the first PA, there was increasing success for hitters in their second PA for each additional pitch type that they faced in their first PA.

I am a little confused. How to you calculate the wOBA of “a pitch?”

Are you just taking the end of each PA and then counting how many pitches that was? For example, if the first PA ended in a K after 4 pitches, that goes into the “pitch 4 bucket” as an out?

And if in the second PA, a batter got a single on the 3rd pitch, and he had seen 2 pitches in the first PA, that goes as a single in the “pitch 5 bucket?”

If that is the case, I am not crazy about that methodology. I would think that there would be lots of selective sampling there.

I mean you are assuming that the chances for every event is equal regardless of the pitch number? As you said, you cannot get a strikeout (or BB) on pitches 1 and 2, so those have to end on a batted ball, so we know there is selective sampling going on there with respect to outcome.

Pitch 3 can be a K, but not a walk, so we don’t like that one.

Pitch 4 in the first PA is not likely to be a walk and it can’t be a walk in the second PA, so I don’t think we like that one either.

Maybe after a while we get random outcomes, but how long does it take? Do we ever get truly random outcomes, enough for you to feel comfortable with your deltas?

It is kind of like who leads off an inning? In the first, it is always the leadoff batter. In the second it probably is not the first 3 batters and probably is 4,5, or 6.

Eventually we get close to random, but never truly random I think (it is asymptotic).

Same thing for these pitch “counts” and outcomes, I think. At what pitch number for each batter, do you think it is close enough to random to trust the results?

Or am I way off base here?

Good question. I did look at this in a way in the article that I linked to at the top of this one.

I split up starters into quartiles, by ERA, and looked at their typical respective pitch selection profiles per time through the order. The best two groups did throw more four-seam fastballs every time through the order than the worst two groups. The bottom two groups had more cutters and sinkers.

I calculated K% and UIBB% for each group, which gives some indication of each group’s decline, but this could be done differently to focus more on the relative penalty of pitchers per time through the order or now I’m thinking of trying per pitch.

I’ll investigate a bit and see what comes up.

I think you have other problems too when you focus on pitch types. I mean since off speed pitches tend to be thrown on pitcher’s counts, you get a lower overall wOBA on them. But, earlier in the game, when a pitcher throws more fastballs than off-speed (I think) you won’t quite have the same effect, so I think you might run into more selective sampling problems. Not sure, just brainstorming a little.

Fascinating stuff, BTW. Great idea. I love your work!

Funny, as I am reading this, I am working with retrosheet data in order to try and tease out the difference between times through the order and number of pitches seen. If I can finish my research tonight, I’ll put up the results on my blog: http://www.mglbaseball.org

Great to see comments within minutes of the Series clinch!

So, yes, the methodology for the red curve in the graph is purely by ordinal pitch instance faced by the same hitter versus the same pitcher in the same game. So it certainly comes with the limitations that I touched on in the article and you detailed regarding when strikeouts and walks become possible. As I mentioned, I have seen other studies produce almost this same pattern.

What I really wanted to do in this case was derive the blue curve in the graph. In this case, I am still counting pitches, but I count separately for each pitch type faced by the same hitter versus the same pitcher in the same game.

So if a hitter saw FF-SL-FF in his first PA, then FF-SL-SL-FF-SL in his second, these were binned under the 2nd FF seen and the 4th SL seen. Not surprisingly, over the course of the game, hitters improve the more that they see each pitch.

The table shows by how much hitters tend to improve on each instance of the pitch types listed. So curveballs are the worst – the wOBA against on the second curveball seen tends to be .009 higher than on the first one that a hitter sees. Four-seam fastballs show an increase of .002 wOBA per pitch seen.

Does that make more sense? I had the same reservations about the methodology for the blue curve, but I felt looking by pitch got rid of a lot of those issues. As you can see, pitches 1-3 are quite flat, and then it starts to rise.

I think you can interpret this as follows: if a pitcher could only throw one pitch, and this pitch was the “average” pitch, then his wOBA against would tend to follow the blue curve, which is much worse than the red curve. The red curve is what actually happens because pitchers of course throw different pitches, keeping the instances of each individual pitch types lower, when wOBA is better than when they are thrown a lot.

Hopefully that at least clarifies what I did…now you can tell me if you find the results interesting as I did, or still have problems with the methodology.

Thanks for the feedback/questions as always MGL!

Sorry replied before seeing your last comment. Yes pitchers do throw a few more fastballs the first time through the order, when I looked at this previously.

You’re also right that with offspeed pitches being thrown on pitchers counts, their wOBA against is generally much better than for fastballs. I didn’t include the graphs in the article for each pitch type. What I did find is that offspeed pitches lose their level of success quicker than fastballs, relatively speaking. This could be because they tend to start out only being thrown in pitcher’s counts the first time through, but by the third time through may need to be thrown in more counts just to keep a hitter from keying on fastballs. That’s an interesting thought.

I thought it was interesting that the rate of decay (so to speak) of the various types of pitches lined up well with usage rates. In other words, offspeed pitches as a whole, which appear to lose their effectiveness at twice the rate (relatively speaking) of fastballs, are thrown with basically half the frequency.

That feels like is what should happen. But maybe that is just luck.

What if you used change in wOBA expectancy as a result of the pitch? (Instead of actual wOBA, that is.) So if a hitter takes a 0-1 strike, the expectancy drops. Might that reduce the problem of selection that occurs by only looking at events that end an at bat?

Thanks for the replies. I will have to cogitate on the data for a while. Good stuff! Very interesting.

One thing I wonder. Would perhaps the times through the order (or just number of pitches in general) penalty be different for pitchers who throw primarily fastballs compared to those who throw a lot of off speed pitches?

“What if you used change in wOBA expectancy as a result of the pitch? (Instead of actual wOBA, that is.) So if a hitter takes a 0-1 strike, the expectancy drops.”

Yes, I always advocate that when looking at individual pitches. I think that is a much better idea.

Looking at PA ending pitches you also have this problem:

Say you have this player in his first 2 PA:

FFFF FFFC

You call that a “1 curve pitch count” in the second PA, but surely the result of that second PA is heavily influenced by the first 3 pitches, which are fastballs and the batter has seen 6 of them by the time he gets to that curve. So when you use only “PA ending pitches” there is a lot of interaction between that pitch and the other pitches in the PA.

This is an interesting alternative Ben, thanks for the raising the idea. I actually calculated expected run differences per ball and strike taken per count (based on wOBA) in my contribution to the upcoming THT Annual. I hadn’t thought to apply that idea here, but I can see the advantages.

Maybe I’ll have to try this….and see how much it changes the conclusions.