The Physics of Going From First to Third

Going first-to-third on the bases in a valuable skill. (via Cathy Taylor)

Euclid, the Greek mathematician known as the “Father of Geometry,” was the first to establish the rules for laying out a ball diamond. Yeah, I know baseball wasn’t even invented yet. Nonetheless, he built the mathematics to describe the behavior of lines and points on flat planes.

You see Euclid’s work whenever you marvel at the exact right angle created by the foul lines as they intersect precisely at the back point of home plate. The perfection of the square with bases at each corner is another jewel of his theorems.

You see Euclid’s work whenever you marvel at the exact right angle created by the foul lines as they intersect precisely at the back point of home plate. The perfection of the square with bases at each corner is another jewel of his theorems.

While Euclid never got around to proving a straight line is the shortest distance between two points, it certainly seems reasonable enough. When the runners go “station-to-station” a straight line is certainly their best bet. However, when trying to collect two or more bases at a time, straight lines are not the best choice.

Let’s understand this by looking at a runner on first trying to go to third base on a single to right field. The defense usually has its outfielder with the best arm in right, so the key for the runner is to minimize the time needed to touch second and move on to third.

Running in a straight line from first to second would require the runner to slow down as he approaches the bag so he can make the turn toward third. Then it would take a bit for him to speed up again. The slowing down and speeding up costs valuable time.

Now you see why ballplayers actually swing out in a wide arc as they run between first and second. They can then maintain their speed as they “round” second and head for third.

Figure 2 is a sketch of the graph of the time to second base versus the length of the path the runner follows. The straight-line path is the shortest but requires the runner to slow down and speed up, which increases the time. On the other extreme, making a very wide arc increases the path distance, thereby increasing the time. Somewhere in between there must be an optimal arc for minimum time.

Mathematicians have devised a solution to this problem. They claim the best path arcs 18.5 feet away from the baseline. The distance along this path is just under 100 feet as compared to the 90 foot straight-line distance between the bases. I’m pretty sure I’ve never seen a runner take a turn that wide.

In any case, that solution is based purely on mathematics, not physics. The question is, why don’t runners usually follow the 18.5 foot arc? To get an answer, we’ll need to think about the forces on a runner moving on a curved path. Understand that I am not talking about the forces along the motion of the runner because at top speed they roughly cancel out. That is why they are no longer speeding up.

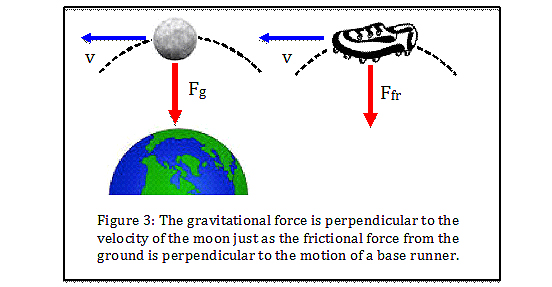

Instead, we need to look at the forces that keep objects moving along a circular arc as shown in Figure 3. Earth provides the gravitational force (shown in red) on the moon that acts toward the center of the moon’s circular orbit. Without this force, the moon would fly off into space in a straight line along its current velocity (shown in blue).

In a similar way, the ground provides a frictional force on the runner’s shoe that acts toward the center of the circular path of the runner. Again, if this force were absent the runner would just keep moving in a straight line along his current velocity. It is the friction between shoe and the ground that keeps the runner turning along the arc.

Vocabulary lesson: these forces acting toward the center causing objects to travel along a circle are called “centripetal forces.” Homework: use the term “centripetal force” in a casual conversation!

Figure 4 shows the foot of runner rounding a bag. If you look very closely, you can see the effect of the frictional force deforming his shoe slightly. To get the bag to exert a large enough frictional force to make the turn, the runner must lean toward the center of his circular arc. The same thing happens when you lean in to make a turn on your bike. Also, roadways are banked to help your car lean into a turn.

Figure 5 shows the forces that act on the runner. Gravity (Fg) pulls him downward, the ground (Fgr) pushes upward, and the friction (Ffr) acting along the ground keeps him moving along the arc. The frictional force becomes larger as the angle he makes with the vertical increases.

Figure 5 shows the forces that act on the runner. Gravity (Fg) pulls him downward, the ground (Fgr) pushes upward, and the friction (Ffr) acting along the ground keeps him moving along the arc. The frictional force becomes larger as the angle he makes with the vertical increases.

Now we can better understand the real question: Can the runner follow the 18.5 foot arc without having to lean in so much that he loses his footing and goes down in a heap? Using the Laws of Physics we can graph the angle versus the speed of the runner along such an arc. The result is shown Figure 6.

The graph shows if you walked this path, the angle you need to lean is zero. You wouldn’t need to lean at all. However, the faster you run the more you need to lean inward.

Michael Clair wrote an article listing the fastest speeds around the bases in 2014. His winner was Dee Gordon, who circumnavigated the bases in a scorching 13.89 seconds on what was ruled a triple and an error. This gives an average speed of 17.7 mph which implies his top speed was probably around 20 mph.

If Gordon was following the 18.5 foot arc, the graph indicates he would have had to be leaning in about 23˚. It is very hard to tell in the replay exactly where he was and what angle he had. However, my gut tells me that he would have crashed and burned had he taken a path that required him to lean in that much.

While there seems to be no definitive evidence to overturn the mathematicians’ claim that the best arc is 18.5 feet from the baseline, at least physics explains why runners need to lean into the turns as they round the bases.

So, in summary, let’s leave the math to Euclid and the mathematicians. After all, the purely mathematical approach is incomplete without using the physics to find the optimal path from first to third. Once again, we see that some of the best experimental physicists on the planet are the ballplayers themselves. They seem to know instinctively the best path to take.

David,

Well done. When I face-plant rounding second in my beer-league softball games because I’m thinking about angles, arc paths and cetripetal forces….well, I guess I’ll get up and have another beer.

Cheers.

AC

Bravo! You did the article homework…quite well too!

Good stuff, Dave. For the mathematically inclined, the paper “Baserunner’s Optimal Path” makes for interesting reading and I’ve posted a copy at my web site: http://baseball.physics.illinois.edu/BaserunnersOptimalPath.pdf

I don’t think it is fair AT ALL to say the underlying research piece involved math and not physics. They use physics, with the interesting simplifying assumption that acceleration is subject to a cap that is not affected by current velocity or direction of acceleration. Your piece could be described generally as thinking about the constraints on sideways acceleration.

It’s also interesting that the mathematicians assert without proof that their path goes further (18+ feet) away from the lines between the bases than any player runs, and yet you suggest they are requiring tighter turns than Dee Gordon could execute. Which implies Dee would have had to run even further outside those lines. But that’s almost impossible since even a circular route would have radius <64 feet, which means <19 feet outside the line between the bases at the midpoint where the line is only 45 feet from the center of the circle.

So runners clearly are able to corner more tightly than you assume, and your photo makes a good point: the stride on which they contact the base is a unique opportunity to turn more sharply than they otherwise can (more lateral acceleration).

If I sum up your piece in light of the work the mathematicians did, I would say that you show their assumption oversimplifies too much and you're prepared to assume that the Dee Gordons of the world have intuitively figured out the best route so math and physics can't offer them any improvement suggestions, and are even limited in ability to explain what they are doing in any way the educated layman can understand. I'm not sure whether to agree. I recognize that, for example, humans are able to solve the best route to catching fly balls rather easily with intuition when the math (based on what they can see with their eyes) seems complex.

But there are other areas where long-standing assumptions by athletes based on intuition have turned out to be wrong in a physics-related way (Fosbury Flop in highjumping seems a good example). My personal bet would be that even good baserunners are a little too slow to move to their right on the way towards first on balls into the outfield (due to all the wrongheaded training they've had about banana turns), but that they do run an optimal path from the point they hit first base.

If we are experimental physicists, it would be interesting indeed to get an overhead video of the path taken by a variety of batters on balls that are potential triples and see just how different their routes from HP to 3B are. If those paths are much different (especially on the 1B-2B leg), they can't all be right, since the differences between fast MLB runners in acceleration and speed constraints isn't that great.

Hmmm. I think I have found a science fair project for my sports minded junior high son.

I was curious whether it is reasonable to think a runner can run full speed around the bases given the arc constraint (much turn at least as sharply as a 63.6′ circle), which leads to the following two data points: radius of the curve on a standard 400M running track is ~36m, so much less sharp. Radius of a standard 200M indoor track is only 17.2m, or about 56 feet. But that track has a 10 degree bank to the curve to help the runners offset centripetal force (even though they are running with shoes and a surface designed to maximize the friction force they can generate).

So probably Dee Gordon cannot run at maximum speed all the way around the bases. This makes the math even more complex–is it better to run the circle route as fast as possible (some fraction of max speed), or run a route with sharper curves near the bases requiring deceleration that you make up for by accelerating to higher speeds on the straighter segments in-between those sharp curves. This would look more like the banana curves we are taught, but I still suspect we’d see enough variety in paths to suspect some runners are taking better routes than others.

Jon,

These are excellent insights. I would encourage you to write something up. If not for THT then for AJP.

David, you make me blush since my last formal exposure to physics was 31 years ago as a college freshman! AJP!?

In any event, do you know whether there is any access to the raw data behind those neat clips we see on broadcasts (mostly playoffs I think) showing baserunner speeds as they go around the bases? That data probably sorts all this out pretty nicely.

NOPE. The baserunner does NOT have to slow down when rounding a base that is FIXED. If you have moveable bases you have to be erect and hit it with your right foot so the base does not slide out from under neath.If the bases are fixed (especially fixed permanently like on some lower rung diamonds) you can run STRAIGHT, use the LEFT foot on the corner and PUSH OFF. No arcs, no slowing down. If anything the push off will make you go faster.

I think Lance Johnson and Tim Raines preached this.

Thanks

So you’re saying a runner can run straight into first base and use the anchored base to change his direction by 90 degrees with no reduction in speed and head straight towards second? That gets the NOPE.

Perhaps what you mean is that the one stride touching the can generate enough added lateral acceleration to allow the runner to otherwise run with small enough arc to maintain top speed. This would be nice to test with an overhead view, since that would make it obvious that the runners turn much more sharply right at the bases. But I really don’t think it is true, based both on personal experience and physics.

With all the other strides around on dirt a “too sharp, too fast” turn results in slipping because the cleat/dirt contact cannot generate enough frictional force. As you point out, at the FIXED base the lateral force is different. As David’s article suggests, the runner’s ability to lean into a turn is much greater at a fixed base: more lean on dirt reduces traction and the frictional force you can generate, yet more lean on the fixed base gives you the equivalent of a banked turn, so you don’t need traction (and you don’t snap your ankle like a twig) to generate lateral acceleration.

If you’re right, observation would show a dramatically tighter turn at the base than elsewhere, and a dramatic lean for the runner at the base. When I watch actual runners rounding bases I don’t see this, including the inside the park homers linked to in the article. I looked for Raines taking a turn, but old videos had few cameras. In his ASG triple in 1987 you see him coming into third at an angle, which means he did round second, not run directly from second to third.

“In any event, do you know whether there is any access to the raw data behind those neat clips we see on broadcasts (mostly playoffs I think) showing baserunner speeds as they go around the bases? That data probably sorts all this out pretty nicely.” I recently wrote a bit about STATCAST data The Physics of Fielding. In this piece I was complaining about the lack of information about the data and the fact that so little of it has been made public. In fact, just to write it I had to make several assumptions. I fear that MLB has made a policy decision to keep everything but PITCHf/x private.