Three for the Memories

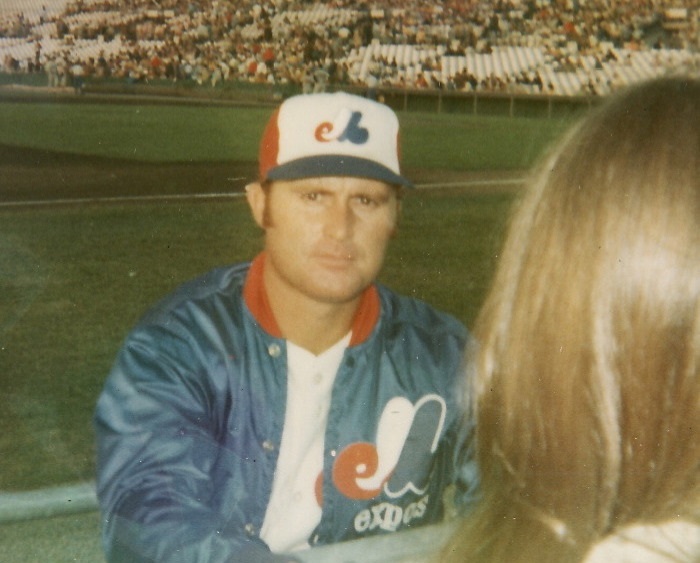

The baseball world lost Ron Fairly on October 30. (via Tony Angiblas)

At one time, I considered myself a young baseball fan, a somewhat rebellious sort who read Bill James’ historical abstracts every winter and always photocopied USA Today’s season-ending statistical wrap-up for each of the 26 teams. When I was a sports talk show host back in the day, those statistical rundowns were vital in assessing wintertime trades and free agent signings. I mean, how else were you supposed to assess whether the Yankees had done a smart thing in trading an aging Mike Easler for an enigmatic Charles Hudson?

Now, at the age of 54, I’m no longer considered young, I don’t read much of Bill James anymore, and don’t subscribe to USA Today. Much of my reading comes from the daily New York City newspapers, where I can follow the exploits of the Mets and Yankees all year long. I also like to read about the game’s history in any one of the hundreds of books that have become part of my baseball library. When I want to look at statistics, it’s quite easy: fire up the computer or the tablet and head over to Baseball-Reference.com, which did not exist in the 1970s or ’80s.

Even at an advancing age, I still find the game, especially its history, fascinating and enthralling. As I grow a bit longer in the tooth, I have also realized a disconcerting trend: the deaths of players whom I remember watching are coming at an increased pace. That’s not a good thing, but it does remind me that I’ve been following this game for a long, long time.

There’s a saying that celebrity deaths come in threes. For baseball players, it sometimes seems like news of their deaths happen in waves, and not just threes. And yet deaths within the span of a few weeks hit home with me. These were players I saw play, whose baseball cards I collected, and who meant more than just the statistics that we might find on the backs of those cards.

None of these players were stars. One was a journeyman catcher, the second was a player who lasted a relatively brief time on the major league scene, and the other was a very good supporting cast player. And yet all three had a considerable impact on good to great teams, particularly in the postseason. They were all important parts of championship clubs, even if we look back at their offensive numbers and come away underwhelmed.

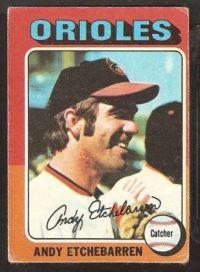

The first player, Andy Etchebarren, died on October 5 at the age of 76, which seems impossibly old for a player I clearly remember seeing. If you grew up with the game in the expansion era you simply had to remember Etchebarren. There was no way to forget this man, if only because of his remarkably distinctive look, one that would have made it difficult to confuse him with Bucky Dent or Lee Mazzilli.

With his dark, bushy eyebrows that usually connected over his nose, Etchebarren proved a worthy successor to 1960s standout Wally Moon as the owner of the game’s thickest and longest unibrow. Etchebarren also had a thick chin, along with ruddy, pock-marked facial features. He looked less like a ballplayer than someone who should have been working on an Edward G. Robinson film about American gangsters.

Far more importantly, Etchebarren was a vital role player on two world championship teams in Baltimore, first in 1966 and again in 1970. That first championship coincided with Etchebarren’s rookie season, when he made the All-Star team despite mediocre offensive numbers. Even at season’s end, the writers came to appreciate his stalwart defense and his adept handling of a young Orioles pitching staff, voting him a 17th place finish in American League MVP voting.

Etchebarren was never a very strong hitter, but his catching skills, his toughness, and his sound fundamental play gave him a tangible place on a number of high-caliber teams in Baltimore. It’s also worth noting that it was Etchebarren who saved Frank Robinson from drowning during the latter’s Triple Crown season of 1966. At a raucous team party in midsummer, Robinson felt compelled to jump into a swimming pool, even though he did not know how to swim—at all. Luckily, Etchebarren noticed Robinson flailing around at the deep end, jumped into the pool, and rescued him before the party turned tragic.

For much of his Orioles career, Etchebarren platooned at catcher with Elrod Hendricks. It was part of Earl Weaver’s extensive platoon system; the Etchebarren/Hendricks combination typified the way Weaver extracted the most of his role players. Hendricks provided more offense, but Etchebarren was the stronger defensive presence.

Etchebarren usually didn’t hit much in the postseason, either, but there were the exceptions of two LCS turns in 1973 and ’74. In the 1973 playoffs, Etchebarren turned into Boog Powell, hitting .357 with a .643 slugging percentage against the Oakland A’s. He would have received more attention for his king-sized hitting output, but the Orioles lost the series in four games as the A’s moved one step closer to another world championship.

When his 15-year major league career ended in 1978, Etchebarren turned to coaching, first at the major league level, and then as a minor league manager. He remained part of the game for 30 years as a coach and manager, giving him 50 total years of service in professional baseball. Sadly his retirement lasted just a few years, which doesn’t seem fair for a guy who lived the game for so long.

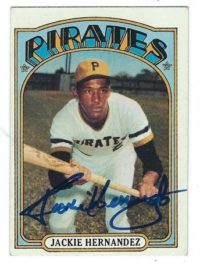

Jackie Hernandez, who died one week after Etchebarren at the age of 79, was a lesser-known player, but a match in terms of his passion for the game. Long before becoming a coach and instructor, the Cuban-born Hernandez signed with the Cleveland Indians as a catcher in 1961. He moved to shortstop, a much better fit for his skinny frame, but the Indians gave up on him in the middle of the 1965 season. Hernandez persevered, signing a minor league contract with the California Angels, then spending some time in the Minnesota system before receiving the break that he needed: expansion baseball. The Kansas City Royals took him in the expansion draft and made him part of their inaugural team in 1969.

Hernandez played a good shortstop for the Royals, but hit very little, batting .222 with no power. After a dip in playing time in 1970, the Royals deemed him expendable, including him as an extra in the trade that sent hard-throwing right-hander Bob Johnson to the Pittsburgh Pirates. The Bucs regarded him little more than a throw-in to the deal, but Hernandez ended up splitting time at shortstop with an aging Gene Alley in 1971.

During spring training in 1971, Orioles manager Earl Weaver noticed Hernandez playing shortstop for the Pirates. He was unimpressed. “The Pirates can’t win the pennant with Hernandez at shortstop,” Weaver told reporters. The manager would come to regret those words, which eventually made their way to Pirates manager Danny Murtaugh, who was not pleased.

Already 30 years old, Hernandez hit only .206 for Murtaugh and the Bucs that season, but he had the kind of range and sure hands that played perfectly on the artificial turf at Three Rivers Stadium. By the time the postseason rolled around, Hernandez had become the Pirates’ regular shortstop. After appearing in all four playoff games against San Francisco, Hernandez continued to man the position during the World Series—against Weaver’s Orioles. He handled 24 chances in the seven-game Series, making all of the plays flawlessly. Those chances included the final play of the Series, a tough, chopping grounder hit up the middle by Merv Rettenmund. Hernandez handled a tough hop well behind the bag, planted himself firmly, and fired a perfect throw to Bob Robertson to end Game Seven, giving the Pirates the title.

Would the Pirates have won the World Series without Hernandez? It’s hard to say for sure, but an aging Alley might not have reached all of those ground balls that Hernandez did. In a taut Series that went to Game Seven, a game decided by one run, who knows what might have happened.

Hernandez saw his playing time diminish in 1972 and ’73, as he lost ground, first to Alley and then to another veteran shortstop, Dal Maxvill. In January of 1974, the Pirates traded Hernandez to Philadelphia for backup catcher Mike Ryan, but he failed to make the Phillies’ Opening Day roster. At 33 years of age, Hernandez would never again play in the major leagues, though he would extend his career playing in the Mexican League.

After finally calling it quits as a professional ballplayer in 1976, Hernandez turned to coaching, both at the professional and amateur levels. He particularly liked working with kids, most of whom would not make the major leagues. Yet, that didn’t matter to Hernandez.

In the early 2000s, Hernandez managed an independent minor league team called the New Jersey Jackals, consisting mostly of non-prospects. On a typical day with the Jackals, Hernandez threw batting practice for several hours, offered players repeated instruction in the areas of both fielding and hitting, and then managed the team that night. Hernandez also tried to make the experience fun, often cracking jokes and making the atmosphere light and loose for his players. It was one of the ways Jackie liked to remind his players that the game was meant to be enjoyed.

One of Hernandez’ former players, Nick Diunte, wrote the following at Forbes.com shortly after Hernandez’ death, “He cared deeply about his players, no matter if they were in the big leagues or the bush leagues.” It’s quite clear that Hernandez loved nothing more than to teach the game.

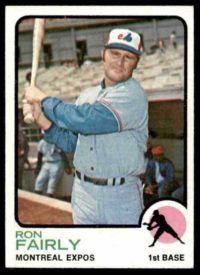

While Hernandez and Etchebarren survived as oft-overlooked role players, Ron Fairly carved out a different kind of career in the 1960s and ’70s. Fairly, who died on October 30 at 81 from the effects of cancer, was also an overachiever. Fairly never hit as many as 20 home runs in a season. For his career, he batted a mediocre .266. Short and stocky and lacking in some of the athletic graces, he could look a little pudgy in a uniform.

Interpreting any of these traits as a sign that Fairly was a below-average player would be off the mark. Actually, hey was a consistent and durable player who understood the art of hitting. Let’s consider just a few of his numbers. He never struck out more than 72 times in a season. He almost always drew more walks than strikeouts. He compiled an on-base percentage of .360 in an era that was mostly favorable to pitchers, not hitters. And he did most of this while playing in two parks that were difficult to hit in: Dodger Stadium and Jarry Park.

As a younger player, Fairly became a key contributor to several standout teams in Los Angeles during the 1960s. A good player during the regular season, he was at his best in World Series play. In 20 Series games, he batted an even .300, while hitting two home runs and compiling a .525 slugging percentage. Yes, Fairly was much more than just a standby on three world championship teams.

After his slow start to the 1969 season, the Dodgers decided to move on from the aging first baseman/outfielder, sending Fairly and infielder Paul Popovich to the expansion Montreal Expos for Manny Mota and infielder Maury Wills. Fairly hated the trade. He was leaving Southern California and a franchise with a history of winning to join an expansion team that played in cold weather and an unglamorous minor league stadium called Jarry Park.

The trade discouraged Fairly, but he didn’t allow it to affect his performance on the field. He continued to play hard for his new manager, Gene Mauch, and played well, even for a bad team destined to lose more than 100 games. Over the balance of the season, Fairly hit .289 with 12 home runs.

In 1970, Mauch used Fairly as his platoon first baseman against right-handed pitching. Fairly responded with some of the best hitting of his career; he batted.288 with an on-base percentage of .402. After an off year in 1971, Fairly bounced back, culminating with his career-best season of 1973. That summer, Fairly drew 88 walks and struck out only 33 times, while lifting his OPS to .880. He also made the All-Star team for the first time, especially impressive for a 34-year-old veteran who was considered to be fading into decline.

After bouncing to St. Louis and Oakland, Fairly again reinvented himself, this time for another expansion team, Toronto Blue Jays. In the spring and summer of 1977, Fairly became one of the bright spots for the first-year Jays. Used mostly as a DH, he hit 19 home runs and compiled an .827 OPS. In July, he became the Blue Jays’ first selection to the All-Star team.

Fairly’s playing career finally ended in 1978. Unlike Etchebarren and Hernandez, he did not turn to coaching, but instead chose broadcasting. For years, he did color commentary on San Francisco Giants games, and later on broadcasts for the Seattle Mariners. In 2011, he broadcast his final game with the Mariners, setting the stage for several years of work-free retirement.

The deaths of Fairly, Hernandez, and Etchebarren garnered a few headlines, but much of the mainstream media gave each of their obituaries only a few lines of newsprint. Sadly, that’s what often happens to players who last appeared in a game 40 years ago. To the true baseball fan, they deserved more, much more, given the length and the quality of their contributions.

All three gave the entirety of their careers to the game—the embodiment of being baseball lifers—and I can think of few compliments any greater than that.

Thanks Bruce. Unfortunately, finding out about old ballplayers’ deaths by accident is the norm. There is no registry for such events. In the ’60’s and ’70’s. the Sporting News publishes an obituary section but back then the players were not of my generation.

This is a fine tribute to the lesser known or marginal players that are so necessary to the game. I’d like to see all of the players get a more detailed obituary when they pass. Etchebarren is on an iconic photograph on the cover of Sports Illustrated from the 1970 WS when Bernie Carbo is called out at home on a tag play, but the ball is clearly in Etchbarren’s bare hand. Fairly was one of the most popular Dodgers and had some pretty big moments.

The beauty of Vin Scully is, he never criticized any player, so as a boy, I probably thought all of the players were much better than they were. Reading your article, this certainly applies to Ron Fairly. I thought he was one of the best.

Ron Fairly was a teammate of Pee Wee Reese, who debuted in 1940; and of both Nolan Ryan and Frank Tanana, who pitched their last games in 1993.

good article