Wade Boggs, Rickey Henderson, and the Fly Ball that Disappeared

Roosevelt Stadium had an antiquated lighting system that led to some problems. (via Jersey City Free Public Library)

In 1976, KISS performed at Roosevelt Stadium in Jersey City, N.J., a show documented in a DVD titled “The Lost Concert.” Two years later, Roosevelt Stadium was the site of another event: The Lost Fly Ball. A fly ball vanished from a Double-A game between the Bristol Red Sox and Jersey Indians on May 28, 1978.

The Indians were an Oakland A’s affiliate but kept the name “Indians” from a previous major league partnership so they wouldn’t have to buy new uniforms. When the Double-A club filed paperwork to join the Athletics organization, some publications listed the team as the “Jersey City A’s,” an inaccuracy that still appears in baseball encyclopedias and websites. The team’s general manager, Mal Fichman, decided to use “Jersey” instead of “Jersey City” to appeal to the entire state.

Rickey Henderson played center field for the Indians. That’s probably a strange image, as we don’t associate Henderson with the Indians or center field.

There was no confusion surrounding the Bristol Red Sox team name. The Red Sox were a Red Sox affiliate. They were based in Bristol, Conn., a two-and-a-half-hour bus ride from Jersey City. Bristol players loved road trips to Jersey City because they were a short cab ride from postgame excitement in New York City.

Bristol had a future Hall of Famer of its own, Wade Boggs. He played outfield, second base, shortstop, and third base that season. Speaking of strange images: Boggs in the outfield, an assignment he had only once in the major leagues.

Boggs, Henderson, and the rest of the players dealt with Roosevelt Stadium’s antiquated lights that night. “It was dark. A ball could get lost because the ballpark was not well lit at all,” said Indians public relations director Jim Hague.

With a thick New Jersey accent, a precise memory, and an entertaining storytelling style, Hague now compares himself to the lead character in the movie Almost Famous. He was 17 years old and somehow convinced his high school to let him take extended absences to travel with the Jersey Indians. He laughs at memories of Henderson cheating in their back-of-the-bus late-night card games.

For home games, Hague was the press box utilityman, working as the stadium announcer, official scorer, and media liaison. “The Jersey Indians ballpark was in major disrepair,” he said. “There’s no question it was dark.”

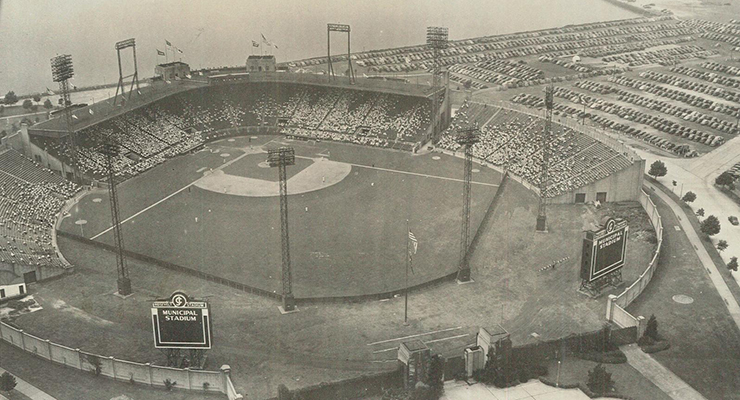

In its first year, 1937, Roosevelt Stadium sold 50,000 tickets to Opening Day, even though the capacity was only 24,000. It hosted baseball, basketball, boxing, concerts, football, ice skating, and soccer over the years. Jackie Robinson collected four hits there for Montreal on April 18, 1946, in his first minor league appearance. The Brooklyn Dodgers scheduled 15 regular-season games there in the mid-1950s as their long-term plans were unfolding. Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young jammed at Roosevelt Stadium the night Richard Nixon resigned.

“We called it ‘Helen Keller Field’ because half the lights were out,” remembered Jersey outfielder LeRoy Robbins. “The person who owned the club didn’t pay for getting the lights fixed. It was a little challenging seeing the ball there.”

“It was a very difficult place to umpire,” said 1978 Eastern League ump Gerry Davis, who went on to work more major league postseason games than any other umpire in history.

“That place was a dungeon,” recalled Bristol outfielder Gary Purcell.

Those dim conditions played a part in a minor league mystery, The Lost Fly Ball. Yes, a fly ball disappeared from an official professional baseball game.

Jersey was batting in the early innings when a right-handed hitter swung at an outside pitch and lifted the ball toward Bristol right fielder Barry Butera.

“I could tell by the angle of the ball coming off the bat that it’s coming in my direction,” Butera said. “I look up, I can’t see it. Nothing. I’m yelling to our bullpen, asking them for help, and they don’t see it either.”

“It wasn’t hit high enough to be blown over the fence,” Boggs added.

The most basic advice ballplayers receive is to keep their eye on the ball. But what happens when the ball disappears?

“We stood there and I kept waiting for the ball to come down, hoping it wouldn’t land on my head,” Butera said. “It was the weirdest thing I’ve ever seen in my life.”

“None of my teammates saw it land,” Boggs said. “Fans said it didn’t come down in the stands.”

Jersey had the lowest attendance in Double-A baseball that season. The team played 68 home games and drew only 28,969 fans, exactly 38,000 fewer than the Reading Phillies’ league-leading 66,969. These days, a successful Double-A operation sells 28,000 tickets for a four-game series. Fifteen of the 30 current Double-A teams welcomed 300,000 or more fans last season.

The Lost Fly Ball game occurred on the Sunday night before Memorial Day. There were fewer than 300 spectators to see, then not see, the puzzling pop-up.

A Class B game in Lynn, Mass. ended early on May 20, 1911, when a fog bank rolled in from the ocean and Fall River’s Buck Weaver belted a ball into blurriness. Nobody could find that ball, either. But this was a different story. While Jersey City is on the Hudson River waterfront, weather was not a factor in this Eastern League enigma. It was a 68-degree night without condensation, fog, haze, mist, murkiness or precipitation of any kind.

Said Butera: “We stand there, stand there, stand there, and the ball never comes down. It never landed. Nobody knows where the ball is. The batter is running around the bases. True story. It was unbelievable. Nobody saw the ball land.”

“If you think about it,” Robbins said, “a ball going up has to come down, (so) where did it come down?”

The mystified managers wanted to know, what’s the call?

Double-A umpiring staffs have three per crew these days. Back then, there were only two to keep up with the speed of the game just two rungs below the majors. The umpires assigned to that game were both well-traveled with previous years of minor league experience, but neither had ever considered how to rule a ball batted into nonexistence.

“The umpires got together and decided to give the batter a ground-rule double,” Boggs reported.

Bristol manager Tony Torchia wasn’t thrilled with an opponent being handed an automatic double, but he had no evidence to suggest otherwise, so he settled back into the first-base dugout without much argument.

We tried to identify the batter who hit the fading fly, but things happen — four decades’ worth of things. The Eastern League told us they don’t have archives earlier than 1981. Hague had boxes full of 1978 Jersey Indians scorecards, but they were washed away in a flood six years ago.

The Hudson Dispatch, the newspaper that covered the Indians daily, folded in 1991. The Jersey Journal followed the team, too, but its archives are inaccessible because of renovations at the Jersey City Free Public Library.

We tried mining records of the visiting team, but The Bristol Press did not go to print on Sundays or Mondays back then. Bristol baseball historians Dave Greenleaf, Doug Malan, and Bob Montgomery hadn’t heard of the play in question. Charlie Eshbach, the Bristol Red Sox general manager in 1978, wasn’t aware of The Lost Fly Ball, either.

We gathered theories on where this fly ball landed but could not get a consensus. Hague wondered if Roosevelt Stadium’s high, white bleachers in right field concealed the ball’s landing spot. One player spotted a kid behind the right-field wall holding a baseball, but another observer said it didn’t look like a game ball. A Class D Kentucky-Illinois-Tennessee League game stopped because of a missing ball in 1939 when a pop-up went up and a dead owl came down. Perhaps The Lost Fly Ball also had wildlife interference?

Eventually, a new ball was put in play, the contest resumed, and Bristol cruised to a 7-3 victory.

The Red Sox won the Eastern League title in 1978. Butera wore his championship ring for years. Boggs finished third in the league in hitting, and Henderson led the circuit in stolen bases.

The Jersey Indians player development contract with Oakland expired, and on Dec. 2, 1978, the Indians signed a working agreement with the Pittsburgh Pirates. They agreed to buy new uniforms this time and rebranded as the “New Jersey Bucs.”

The enthusiasm for the new era of Jersey City professional baseball was short-lived. New Jersey Bucs hats became collectors’ items because the team never played a game under its new identity.

In January of 1979, a windstorm blew over one of those ineffective light stands and sent it crashing through the Roosevelt Stadium roof.

“It damaged the press box and the upper grandstand. It was beyond repair,” said Chuck Johnson, an Eastern League employee at the time. “Bolts were rusted, the grandstands were collapsing. Inspectors went in, and they condemned the place.”

Suddenly, the Eastern League had a team without a home. After shuffling around other cities and affiliations, the New Jersey Bucs franchise moved to Waterbury, Conn.

“We went down there to Jersey City and drove a couple of U-Haul trucks back to Waterbury. It was boxes full of uniforms, bats, balls and things of that nature that were left over. It was a one-day trip,” Johnson said.

And just like that, the team disappeared, just like its fly ball a few months earlier.

References & Resources

- Telephone/email correspondence with Wade Boggs, John Burbridge, Barry Butera, Gerry Davis, Charlie Eshbach, Dave Greenleaf, Jim Hague, Jerry Izenburg, Chuck Johnson, Doug Malan, Scott Merzbach, Bob Montgomery, Anthony Olszewski, Gary Purcell, LeRoy Robbins, Bill Rosario and David Vincent.

- AccuWeather

- Jersey City Free Public Library

- The Bristol Press

- The Brooklyn Daily Eagle

- The Hudson Dispatch

- The Jersey Journal

- The Pittsburgh Press

- The Reading Eagle

- The Union City Public Library

- Baseball-Reference

- The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball

- The Kitty League

- Retrosheet

- The Society of American Baseball Research

Great work; prior to this reading I was not aware of these 1970s Eastern League adventures.

Previous to this article, I knew of Roosevelt Stadium as the site of Jackie Robinson’s pro-debut and a place where the great Bob Seger and the Silver Bullet Band ( his was their Night Moves album) had to open for the mediocre KISS in 1976. (Or did KISS close for Seger?)

After reading this history of the stadium, I clicked around the web to see Roosevelt Stadium’s art deco facade; I did find images of that facade but wish to share this link to art from the Hudson County (NJ) Community College Library depicting Robinson seeming playing at Roosevelt Stadium by moonlight and Willie Mays hitting by sonar there. It seems artist Paul Lempa latched onto the “dungeon” lighting as a motif in his rendering.

http://www.hccclibrary.net/dodgers/

Now hold on there …

I saw that tour. In Pittsburgh, it was (in order) Artful Dodger, Bob Seger and KISS, and not just KISS but KISS on the “Destroyer” tour, just about as good as KISS was ever going to get, back when they were still thought of in some circles (*cough* Tipper Gore *cough*) as a threat to the fabric of society. Good enough that many years later on one of their endless cha-CHING tours KISS replicated that show, IIRC. I can still visualize them opening with “Detroit Rock City/Kings of the Nightime World.”

Props to Seger, he was terrific, but that whole show was amazing. I still cite it as one of the best concerts I’ve ever seen.

But if you think KISS at its best was mediocre, I guess I’m not going to change your mind.

Tipper Gore and the PMRC emerged in the early 1980s, by which time KISS had long since passed their peak. The pushback against the band in the 70s was from conservative religious groups otherwise obsessed with backwards masking and demonic/Satanic lyrics and imagery. Tipper was just upset about bad language, and a good 5 years later.

You are correct, of course (and I should have checked the timeline first), but in any case she provides a good “Oh yeah, her” avatar from (roughly) those days for that kind of attitude toward rock music and strangely dressed people (could have used Anita Bryant as well, maybe, but I think Tipper triggers more memories). Also, I’m older now and time seems to compress. I just recall a sort of “lock up the wives and children” panic prevalent in some quarters when KISS would come to town. And for all I know, that might have been generated completely by some clever person in the KISS P.R. department in the day.

Strange how it happens that as KISS’ careers spiraled out into the money monsters they would become, they became the kind of band older folks would take their kids and grandkids to see. They went from fearsome to lovable. Same thing that happened to Alice Cooper.

A good day to you, sir! Rock on!

For what it’s worth, it was Dee Snider, from Twisted Sister, who testified before a mid-1980s U.S. Senate committee, in opposition to the PMRC agenda.

Mr. Buc,

With a tone of conciliation and brotherhood, I stipulate that that roster of acts could have had value for you and also me.

I was nine-years in ’76 and do not recall those acts getting out to my childhood home near El Paso, Texas. I do remember fondly those musicians coming into my life from Chihuahua on a 50,000-watt border blaster station–XROC 80.

I did not value KISS then or since. That is my value–no effrontery intended to the KISS Army. I do believe that my bro-worship of Bob Seger started in ’76 with “Night Moves” and grew with each discovery that I made in his catalogue.

Lastly, as I “hum a song from 1982”, Buck Weaver’s referenced fly-ball into the deep night can be evoked in the title chorus of “Night Moves.” “…ain’t it funny how the night moves/when you just don’t seem to have as much to lose.”

Nicely said.

I’ll give you this: “KISS Meets the Phantom of the Park” is one of the worst movies I’ve ever subjected myself to.

Rock on.

Great article – it was a fun story while providing a context for the state of minor league baseball affairs in the late 70s and the end of baseball in Jersey City. What are your thoughts on where the ball went?

Thank you, Eric.

Good question. It’s a mystery. Maybe the ball will land one of these days.

Tim

David Copperfield was born David Seth Kotkin, on Sept. 15, 1956, in Metuchen, N.J., a short jaunt down I-95 from Jersey City.

Can anyone account for his whereabouts that night?

Ha!

My brother and I were at this game. I’ve told people about it over the years, but this is the first time I’ve ever seen it confirmed. I was 17, my brother was 21, and it was the only time I ever went to Roosevelt Stadium. My brother was the kind of person who wanted to say he’d been somewhere before it closed forever, so we went. It was pretty obvious it didn’t have long to go.

I remember the cavernous dark interior of the stadium; there was hardly anything left at the time like concessions or anything much at all. Just a guy selling pennants, I think. Maybe some guy selling hot dogs from a box. The restrooms were ancient. We sat on hard cement bleacher like seats, I’m almost sure, even though we were pretty much directly behind home plate.

I don’t remember it being that dark yet. Probably enough for the lights to be on, but I had no problem seeing that ball. It went high – very high, from our vantage point, into right field. And then – it disappeared. It just disappeared! One of the strangest nights of my life. No one could account for what happened to it. We never lost sight of it; it was just gone. It took a while to understand that everyone had just seen the same thing and there was no rational explanation (no birds or anything either).

Richard,

Thank you for posting your experience. It’s amazing to hear from someone who was in the stands that night!

Tim

Cool article, and awesome comments by people who were at the game and the Kiss concert. Sometimes the internet is great.

Grew up in Jersey City in the 50’s and 60’s. Roosevelt Stadium did not have “High white bleachers in right field” as reported in the story. In fact it had no bleachers at all. I attended a lot of those games, including Dodger games and most of the rock concerts held there including CSN&Y the night Nixon resigned. Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon tour there was, without a doubt, the greatest show I ever saw.

Mike,

Thank you for reading the article. The city spent $40,000 in February of 1977 to “remodel the stands,” according to newspaper coverage at the time. The bleachers looked different in 1978 than they did in the 1960s.

Tim

Both the left and right field areas were painted white when there was a one-game tryout between the Reading Phillies and Cleveland Class AA Williamsport affiliate (they were looking for a new location and tried Jersey City for one game) in 1976. At one time, there were wooden seating in that area, but most of it was beyond repair, so the wooden bleacher-style seats were removed and what was left was painted concrete stairs that were indeed white.

And for the person who said that the team owners didn’t pay for the repairs, that’s wrong. Roosevelt Stadium was owned and operated by the city of Jersey City. It was known for the longest time that the powers-that-be wanted to have the eyesore removed and replaced with housing (which is what eventually took place). The city was not going to pay for major repairs or renovations to Roosevelt Stadium.

When the light structure collapsed, that was enough damage to condemn the place and rule it unfit for night play (although the high schools and colleges played day baseball and football games there until it was razed in 1985).

And I still, for the life of me, remember a ball being lost in the air and never coming down.

Such is the folklore of minor league baseball. Some crazy things do take place.

I was so happy that Tim contacted me and had me contribute to his article

Jim Hague

Great stuff Tim! Thanks for the effort to tell such a great Minor League Baseball story!

Any chance that Bristol Red Sox historian Bob Montgomery is the same Bob Montgomery who played catcher for the Boston Red Sox during the 1970s?

Cool article. Things have changed. Minor league baseball, especially AA is a much bigger deal nowadays.

I think, but I might be wrong, that even AA teams make money from jersey sales, and wouldn’t mind changing their uniforms. But then again, changing the team name might be bad for business as the fans are less likely to identify with a new name. Having the farm teams adopt the big league nickname doesn’t sound like a good idea. It sounds better to have a name with a local ring to it.

Also, can’t imagine a high school kid with that much responsibility on a minor league team nowadays. College graduates are taking unpaid internships and are lucky for it.

Indeed, times have changed. Getting paid for work is apparently now a perk. .

It was a fun story while providing a context for the state of minor league baseball affairs in the late 70s and the end of baseball in Jersey City. Thanks for the effort to tell such a great Minor League Baseball story!