When Baseball Was King

For one Thanksgiving, baseball — not football — was king. (via Public Domain)

In 1863, Abraham Lincoln, in the midst of the Civil War, declared Thanksgiving a federal holiday. While contemporaneous Americans associate the holiday with the Pilgrim harvest at Plymouth in 1621, such celebrations were commonplace in Europe and its colonies in the Americas. Harvest festivals and periodic days when civil and religious authorities called upon the populace to give thanks for religious figures, battlefield victories, and other important events encouraged the development of civic pride and nationalism.

In the decades following the Civil War, the emerging sport of baseball weaved itself into the broader fabric of Thanksgiving and American life. While the regular baseball season had long since ended, local businesses, athletic clubs, and neighborhood teams filled the void. The games often occurred alongside other activities like shooting contests, relay races, dog races, and other festival activities. Often they were part of charity events raising money for orphan and poor relief. In 1887, the Nassau Athletic Club in Brooklyn held its third annual charity “burlesque games” featuring a greased pig wrestling contest, a cranberry pie race, and a not-at-all-problematic baseball game between “Chinamen and colored men.”

In San Francisco, Californians celebrated Thanksgiving similarly to their brethren on the opposite coast. On November 24, 1887, San Francisco featured a host of theatrical performances, charity events, and “various other amusements, from peppering pigeons with leaden pellets and betting on horse races, to assisting in social exercises and responding to toasts.” The highlight of Thanksgiving, however, was a baseball showcase the city had never seen before.

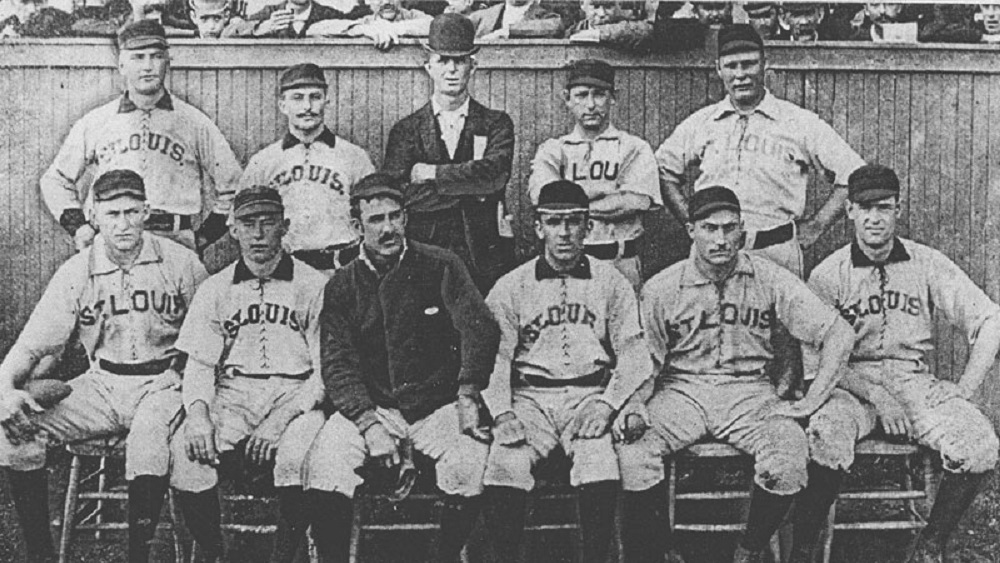

Four professional baseball teams had come to the West Coast to play a series of exhibition games against one another and teams from California. While other pro teams had wintered in California before, the New York Giants, who more than 70 years later would make San Francisco their home, were making their first trip west. The Philadelphia Quakers and Chicago White Stockings of the National League and the American Association champion St. Louis Browns had also sojourned to the City by the Bay.

Thanksgiving would be the highlight of the trip. The Giants would play two games at the Haight Street Grounds: the first against the Haverlys, named after the famed theater, from San Francisco, and the second against the Greenhood & Morans, named after a pair of clothing store owners, from Oakland.

Over at the Central Park Grounds, the Quakers would face off against the White Stockings in a match-up between the second- and third-best teams in the National League. In the afternoon game, the Quakers would battle the Browns.

The White Stockings and Quakers had whet the appetite for the Thanksgiving games by playing a Sunday afternoon game on November 20 at the Central Park Grounds.

Before the teams even arrived at the field, anticipation for the game had taken hold in San Francisco. Around noon, crowds began gathering at the fashionable Russ House hotel where the players were staying. As the teams started their journey to the park, “Sporting men, lovers of the manly art, eye-glassed dudes, and the small street urchins” sought spots on the street to watch the impromptu parade. While the Quakers and Browns looked sharp in their crisply clean uniforms, the White Stockings failed to impress. The San Francisco Examiner complained, “Were it not that ‘Beauty unadorned is best adorned’ the Chicagos would have looked a dingy crowd.”

By the time the teams reached Central Park, the excitement had reached a fever pitch. The Examiner reported, “there was a surging howling, rustling mass of humanity ready to storm the citadel if anyone sought to bar their entry.” A detachment from the Salvation Army attempted to steer the massive crowd away from the field using a cornet, a large drum, and a hearty dose of yelling. Enterprising vendors selling “genuine Arabian gum drops” and “Boss candy” sought to take advantage of the large crowd to sell their wares. Instead, baseball-crazed patrons shoved them aside.

Once inside the park, the 10,000 to 15,000 spectators filled every available seat. The White Stockings played well. Their fleetness of foot in the field especially impressed the fans. “The Chicago girls are world renowned through the alleged size of their feet, but if their baseball brothers have inherited a similar abnormal development of their pedal extremities it in no way interfered with their covering the ground when any chance of a run was visible,” wrote The Examiner. Chicago pitcher Tony Mullane “divided his time between sending in red-hot balls and masticating a quid of tobacco” as the White Stockings won, 12-3.

The poor quality of play from the Quakers, on the other hand, drew the crowd’s ire. The Philadelphians committed six errors and allowed the White Stockings to score nine runs across the third, fourth, and sixth innings. For their part, the Quakers managed to scrape together only three runs in the bottom of the third. The Examiner complained, “Had a California club put up the game the Phillies did yesterday they would have been hooted and jeered from the crowd.”

One Browns player speculated that the large crowd disrupted the flow of the game, swallowing up several popups that would have been outs under normal circumstances. The Examiner speculated that the Quakers may have played poorly because, even as a warm afternoon sun shone down on the field, “the only beverage allowed the players to keep up their spirits was water.”

Additionally, an altercation in right field delayed the game 20 minutes. Thomas McCall, a young, inebriated man, had been berating the fans around him, demanding someone bet on the outcome of the game with him. When his fellow spectators failed to reciprocate, McCall called them “vile and indecent names.” After being escorted from the crowd by two San Francisco police officers, McCall broke free and resumed his disorderly behavior. Officers Stanton and McCarthy then placed McCall under arrest but not before McCall kicked Stanton in the eye and “blackened” McCarthy’s shins. When called upon to account for himself in court the next day, a sober McCall offered no excuse for his actions. Judge Hornblower sentenced him to four months in the House of Correction for battery and using vulgar language.

That afternoon also marked the end of the fall season of the California League. As with most professional leagues of the time, the number of teams shifted from year to year and even month to month. In 1887, the California League had four teams: the Haverlys, Greenhood & Morans, the Pioneers, and the Atlas.

The California League teams had plenty of major league-caliber players on their rosters. Twenty-one year old George Van Haltren had played for the White Stockings in 1887 before returning home to rejoin the Greenhood & Morans for the season’s stretch run. Greenhood & Morans’ right fielder, Bob Blakiston, had played for the Philadelphia Quakers and Indianapolis Hoosiers from 1882 through 1884. In 1884 and 1885, catcher Jim McDonald bounced among the Union Association, American Association, and the National League before returning to California.

Haverlys catcher Lou Hardie had made brief appearances with the Quakers and the White Stockings in 1884 and 1886. Later, in 1890, he played 47 games for the Boston Beaneaters, and in 1891, 15 games for the Baltimore Orioles. From 1888 to 1890, third baseman Pete Sweeney played in 134 games, hitting .209/.280/.269 with a 49 OPS+, for the Washington Nationals, Quakers, Browns, and Louisville Colonels.

The battle for the league championship came down to the last day of the season. The league-leading Pioneers lost to the Greenhood & Morans, 5-2. While the Greenhood & Morans won, pitcher Van Haltren had complained to the umpire about heckling from the Pioneers shortstop, Huey Smith. Smith, known in the California league for his taunting, had unleashed such devastating witticisms like, “Turn the gas up and light onto this one!” and “Slap it out, he’s pie!” on the young hurler. Finally, the umpire ordered Smith to stop his pestering lest he face a fine.

With the Pioneers loss, the Haverlys had a chance to claim the league championship for themselves. The opposing Atlas, however, took the season’s final game, 9-8 in 10 innings, granting the Pioneers the pennant.

The San Francisco Examiner published mostly glowing profiles of the Pioneers players, promoting the league and the upcoming exhibition games with the teams from the East. Second baseman Charles Gagus was known for his reputation as a “kicker and his proclivities in this direction have been the foundation of many a joke.” Infielder Nick Smith, who hit the only home run at the Haight Street Grounds, earned himself a gold medal from an admirer for his efforts. He was well-liked by the young female fans: “Nick is a perfect gentleman on and off the diamond and many a fair one’s heart flutters whenever he takes his position at the bat.” Right-fielder Hypolite Perrier, however, was the victim of some late 19th-century fat-shaming. The 190-pound Pierrer, who was “slightly above the average height” was “an active ball-player for so large a man.”

The yet-to-arrive New York Giants, however, garnered the most excitement from the fans. Featuring a roster packed with stars like shortstop John Montgomery Ward, the Ivy-League educated, labor rabble-rouser with a famous actress for a wife, Tim Keefe, “America’s greatest pitcher,” and the “tall, giant-formed individual” first baseman Roger Connor, the Giants finally crossed the Golden Gate Bridge on Tuesday, November 22.

Local reporters had piled onto the train south of the city to get a look at the players and their traveling entourage. Inside the Pullman cars, “Piles of uniforms, bat-cases, shoes and other belongings of the diamond-field were heaped about promiscuously.” While Keefe and Connor warranted a fair amount of attention—Ward had yet to arrive in California after negotiating for the recognition of his Brotherhood of Professional Base Ball Players from the National League owners—Michael Joseph “King” Kelly was the star attraction. The Examiner took a special interest in the “$10,000 beauty.” An Examiner reporter walked through the Pullman car and encountered Kelly as he “entered from the lavatory, where he had been engaged in putting the finishing touches to a hastily completed toilet.” Kelly was “not handsome: a three days’ growth of bristly red beard, it is true did not add much to his personal appearance. Tall, well-formed, and the possessor of an extremely intelligent face, Mike will pass muster as a good-looking man; but not handsome.”

The Examiner also reported on the team’s superstitions. Kelly “counts his success by the number of girls that admire him within his hearing. If the number is odd he is bound to achieve success with the stick.” Connor was always “intensely happy when he spies a load of barrels standing on end.” The presence of vertical barrels often meant a home run, a barrage of hits, and the absence of errors. Utility man Buck Ewing had an affinity for African-American women: “Passing one on the street does him some good, being brushed by the skirts of one helps him a great deal, but to walk between two of them makes fortune a sure thing.” Keefe took “notice of crosseyed people with reluctance.” Catcher William Brown believed in burying a horseshoe under home plate for good luck.

On Thanksgiving, the Giants took the field for their first game in San Francisco. Five thousand people had packed themselves into the Haight Street Grounds on the raw and cold day as clouds blocked the sun. The field was soft, making running and fielding difficult.

In the top of the first, the Haverlys scored their only two runs of the game off Keefe. The Giants tied the game in the bottom of the first and scored another seven runs, easily winning 9-2. The Examiner complained that the game was a “dreary blank.” Kelly mustered three singles and a triple, scored three runs, and stole three bases while catching Keefe. Ewing, filling in at short for the absent Ward, had two singles, a triple, and two steals of his own.

In the afternoon game, the Greenhood & Morans toppled the Giants, 10-4. The crowd of 15,000 “cheered, howled and acted like lunatics during the nine innings required to do up the visitors from Gotham.” The Morans scored two runs in the first to open the game, but the Giants evened the score at two in the bottom of the second.

Kelly, who played well in the first game, came on in relief of Keefe. Kelly, however, who pitched intermittently throughout his career, annoyed the crowd with his slow and ineffective pitching. The Examiner complained, “Had he been placed there first, electric lights would have been necessary to finish the game.” Kelly’s laborious pitching dragged the game out to an excruciating two hours and 10 minutes. The paper gleefully reported the Morans “lit on to him their easy Western way, placing the sphere wherever their fancy pleased them, and giving the stalwart Giants in the outfield all the exercise necessary to keep their blood in perfect circulation.”

The games over at the Central Park Grounds, however, elicited much less enthusiasm from the crowd. While the White Stockings beat the Quakers, 6-5, the game “lacked excitement” according to The Examiner. Quakers pitcher Alex Ferson had little control over his pitches and allowed the White Stockings to grab a 4-0 lead after two innings. The Quakers scored five runs in the bottom of the third and took the lead. The White Stockings, however, scored two runs in the top of the eighth and held on for the win. Chicago second baseman Fred Pfeffer stood out for his glovework, snagging three difficult pop-ups.

In the second game, the Browns triumphed over the Quakers, 12-3. Dave Foutz of the Browns “handled the sphere in a masterly manner” allowing only eight hits and no walks. While the Quakers scored three runs in the first, they failed to push a run across the plate the remainder of the game. Philadelphia remained “slow and amateurish in their playing.” They were like “an amateur team battling with professionals, and bases were purloined by the Browns before the other team seemed aware of it.”

Browns third baseman Arlie Latham, however, won the hearts of the crowd because of his exuberant play and his mouth. He began talking in the second inning and never stopped. The loquacious Latham admonished the umpire for being too slow in returning the ball to the pitcher. He yelled encouragement at his teammates and traded barbs with the crowd. Latham, who had three hits and stole two bases, refused to let a single comment pass without offering a response.

Baseball had fit seamlessly into Thanksgiving in San Francisco. The Examiner reported that despite the cold weather “the morning was occupied in attendance at church or the baseball games…and the afternoon was passed in witnessing the exhibitions by the Eastern players of their skill on the diamond.” Earlier in the week, the paper had declared that while “certain unappreciative” writers had labeled baseball a fad, the sport had “manifestly come to stay.” Baseball’s success, the paper concluded, “must be the outcome of something in the genius of the American people which the system of the game exactly suits.”

As the people of San Francisco celebrated a wonderful day of baseball, the Sacramento Record Union bore a forbidding headline: “Is Baseball Doomed?” while reporting on a college football game between Cornell and Lehigh University.

While football games have come to dominate Thanksgiving, for a brief moment, baseball was king.

References & Resources

- Baseball-Reference

- “Our National Game” The San Francisco Examiner, November 21, 1887

- “Pioneers: Champions of California for the Season of 1887” The San Francisco Examiner, November 21, 1887

- “Baseball Amateurs” The San Francisco Examiner, November 21, 1887

- “Disturbed the Game” The San Francisco Examiner, November 22, 1887

- “Mike is Here: The Beauty and the Famous New York Giants in Town” The San Francisco Examiner, November 23, 1887

- “Thanksgiving Day” The San Francisco Examiner, November 25, 1887

- “Billy Boy, Van.: George and the Greenhoods Do Up the Gotham Giants” The San Francisco Examiner, November 25, 1887

- “The Athlete’s Holiday Fun” The New York Herald, November 25, 1887

- “Is Baseball Doomed?” Sacramento Record Union, November 25, 1887

‘The San Francisco Examiner complained, “Were it not that ‘Beauty unadorned is best adorned’ the Chicagos would have looked a dingy crowd.”’

Love this stuff. Exactly how much is this ingenuous, I don’t know!

Great article! However; “The Giants finally crossed the Golden Gate Bridge on Tuesday, November 22.”

50 years too soon https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Golden_Gate_Bridge

Looking forward to your book.