Bubble Wrapping History: The Search For a New South Jersey Baseball Hall of Fame

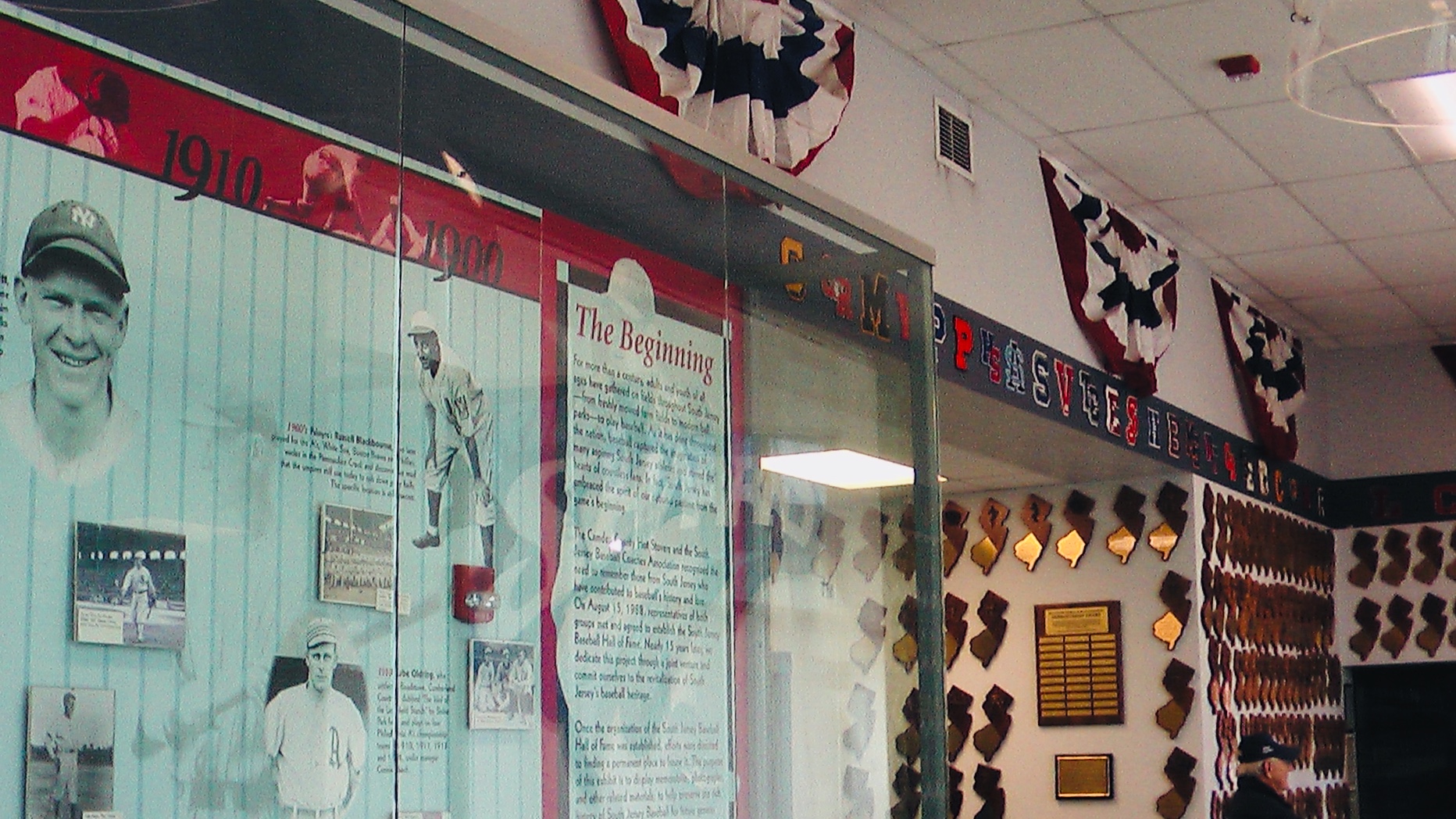

Campbell’s Field was once the home to the South Jersey Baseball Hall of Fame. (via R’lyeh Imaging)

In the early hours of July 16, 1945, the United States government put aside any passing concerns for the citizens of Albuquerque, New Mexico, and went ahead with the first nuclear bomb test in human history.

Almost exactly three years later, on a much less eventful morning in Greenwich Village, Bell Labs revealed its latest production: the transistor, a component that would replace the vacuum tube in radio transmissions and further the reach of humanity’s communications.

In The Idea Factory: Bell Labs and the Great Age of American Innovation, Jon Gertner marks this pair of developments as the beginning of “the two most important technologies of the twentieth century.” With one of them, America introduced the world to heinous destruction on a biblical scale. With the other, America’s pastime was able to reach a new generation. That pastime being baseball, not heinous destruction on a biblical scale.

As the years passed, America’s youth would come to know both well. The threat of nuclear annihilation would send them ducking under their desks, and transistor radios would allow them to listen as their local nine played into the school year. Baseball had put itself into both technologies, either as a passing cultural reference — Gertner says it only took a “baseball-sized chunk” of plutonium to trigger a mushroom cloud — or as a method of distraction — transistor radios allowed the 1969 World Series to be broadcast from Shea Stadium in New York to the students in Mrs. Kimball’s English class at Toms River Intermediate in Southern New Jersey.

Don Borden was in that class and he and a few of his classmates, transistor radios snaked up their shirt sleeves, earpieces obscured by leaning on their hands, were utilizing the technology available to them to follow the action.

“Mrs. Kimball was a very stoic older teacher, calico dresses, very, very prim and proper,” Borden recalls. “At some point and time, [the Orioles’] Paul Blair hit a drive to deep left center field, and Tommie Agee was the Mets center fielder. The Mets’ announcers are like, you know, ‘back back back back…’”

“Tommie Agee makes a phenomenal game-saving, potentially series-saving catch. And the six or seven of us are [cheering], and Mrs. Kimball had her back to us — ’ll never forget this, it’ll go to my grave — she turned very slowly, and said, ‘Gentlemen, and I use that term loosely, if you’re going to be so rude as to be listening to the World Series as the rest of us are tending to our studies, the very least you could do is share what happened to the rest of the class.”

South Jersey wasn’t the only place in the country where kids were sneaking a listen to the World Series in 1969, though it may have been the only one in which their teacher asked what the score was. Baseball, by this time, was in every town, its reach furthered by transistor radio broadcasts, both public and clandestine. It didn’t thrive just in New York and Baltimore, either — for every row of houses and a post office, baseball was there, swiftly building upon its early legacy. From those South Jersey backyards and English classrooms would emerge both names we recognize, as well as others who would remain local legends and disappear into other walks of life without a career batting average we can cite offhand.

Every generation or so, you get a Goose Goslin (Salem, New Jersey) or an Orel Hershiser (Cherry Hill High School East) or a Sean Doolittle (Shawnee High School) or a Mike Trout (Millville Senior High School), but for those who flamed out or couldn’t keep up, there is little but quickly yellowing box scores to commemorate their accomplishments on the diamond. Playing baseball well is not a common thing, even if you never reach the peak of the sport, and memorializing that accomplishment allows your story to live on, even if it ended not long after the first chapter.

That remains the intent of the South Jersey Baseball Hall of Fame, organized and curated by the Hot Stovers Baseball Club, a not-for-profit organization whose mission is “to promote sportsmanship and participation in South Jersey baseball, to keep the area’s baseball heritage alive through the South Jersey Baseball Hall of Fame, and to provide college scholarships to well-deserving high school scholar athletes.” You can still see Campbell’s Field, the minor league stadium that once housed the SJ HOF, from the seat of a PATCO train as it rattles the Ben Franklin Bridge crossing from Philadelphia into Camden, New Jersey; it’s the pile of rubble, bulldozed neatly along the outline of an infield.

Courtesy of Tom Haas.

Tom Haas, the president of the Hot Stovers Baseball Club of South Jersey, which oversees and curates the South Jersey Baseball Hall of Fame, had been informed a year and a half before Campbell’s Field was demolished that his organization would have to find a new home for the SJ HOF because the old one was going to be hit by a wrecking ball. They got to work looking for a replacement venue, knowing that the day would come when they would have to enter the empty stadium with all the manpower they could muster, pack up fragile exhibits, and carefully transport the plaques, signs, and delicate memorabilia on display.

One morning, Haas realized as he opened his newspaper, that day arrived.

“[They told us] ‘we will let you know, we will give you plenty of time to get that stuff out of there.’ We seen that article where [George] Norcross said they were going to tear [Campbell’s Field] down,” Haas says, “and we were pretty sure it was time to move the stuff.”

The RiverSharks had moved out and Campbell’s Field had become a derelict. Haas had been told that one of the reasons Campbell’s Field hadn’t been able to secure a new tenant was because the place needed two million dollars in renovations. He and some fellow Stovers could see every penny of the damage, dripping out of leaks and cracking through the walls, as they explored the remains.

“The stadium was in really bad shape,” Haas says. “The field might have been fine, but the underside of the stadium…. It was in bad shape. We went through the locker rooms. Things were falling apart, pipes were breaking. That was one of the reasons that nobody went in there.”

Which was fortunate, because somebody could have gone in there after the facility had been left uninhabited. There was not a real line of defense between Campbell’s Field as it sat there, waiting for death, and any interested party walking by who was curious enough to hop a fence. The South Jersey baseball treasures they would have found inside would have been worth snagging a pant leg: A bat once held in Goose Goslin’s hands. A helmet that once sat on Mike Trout’s head. Sheets of glass, displaying historical info that would be all too tempting to anyone walking through an abandoned ballpark looking for something to break.

The threat of an unprecedented memorabilia heist had weighed on Haas and the Hot Stovers. It took them three Saturdays to pack up almost 100 years of history in the South Jersey Baseball Hall of Fame. A group of five or six Hot Stovers showed up, but in the final week it had dwindled to three, and the club recruited any spare sons-in-law to help before the professional movers came in to handle the glass.

Courtesy of Tom Haas.

“Yeah, we were a little nervous about them breaking the glass,” Haas says. “It took four guys to lift one piece of glass, they used those suction cups. They made two trips, and then the movers had a real big truck and they only used one trip — everything, all the framing, all the boxes. Our membership did a great job, because we had packed everything. All they had to do was pick the boxes up and put them in the truck.”

The question remained, as it had for most of a year, where all of this baseball history was going to go. Soon, Campbell’s Field would be dust. They needed a home for the Hall of Fame that wasn’t abandoned, targeted for destruction, or wrapped in leaking pipes. Plan B was far from ideal.

“I said, I can’t put it in my garage, I got no space in my garage,” Haas recalls. “We were asking our members, ‘You got any room in your garage to put this stuff?’”

Courtesy of Tom Haas.

The hall looked like it was going to be scattered, still boxed, among attics, dens, and basements across the southern half of the Garden State, limiting its effectiveness. The whole point of the SJ HOF was to stir interest in baseball among young fans. Finally, the Hot Stovers found a solution at Camden County College when they reached someone with experience in being a young baseball fan.

“My father was a very, very good baseball player in the shore conference in the Freehold Regional [High School District],” Don Borden says. “I think one of his greatest wishes was that my brother and I would have been better baseball players, but candidly, neither of us were. We tried. Let’s just say that.”

The first thing Borden, now the president at CCC, wants to make clear is that a lot has changed for him about baseball since Mrs. Kimball’s English class.

“I was originally from Ocean County, we have mixed allegiances,” he explains, responding to accusations that he used to root for the Mets. “I was always a follower of the Phillies, but to be honest, I also leaned a little bit towards some New York teams. I had a dual allegiance that ended at about the age of 19. I was a child — I was stupid, I made a lot of bad decisions.”

Borden had worked his way up through high school administration, serving as athletic director, principal, and superintendent for Audubon High School, an institution synonymous with baseball in South Jersey. He became president of Camden County College in 2016, the position he was holding when an intermediary connected him to Tom Haas and the Hot Stovers during their search for a new facility.

“Prospective new facility,” Borden stresses. “We’re in the design stage.”

Making architectural promises in education is a delicate dance, so Borden is very deliberate about what he says. Right now, the new gymnasium and athletic facilities CCC is looking to develop exist only in blueprints, blueprints Haas and other Hot Stovers have seen and been told represent a two- to three-year timetable. When they are complete, the plan is for the South Jersey Baseball Hall of Fame to be housed in a part of the brand new CCC athletics facility, including a banquet hall for annual Hall of Fame class inductions and other functions. Currently, banquets are held at Masso’s Crystal Manor in Glassboro and meetings are held at The Taproom & Grill in Haddonfield, with occasional jaunts to the Voorhees Diner on the other side of the Jersey Turnpike.

South Jersey is a place with a shifting definition. Everybody is pretty sure it includes seven counties, but corners and slivers of others may or may not fall within its borders. In 2015, the media turned to the people to ask which pieces went where. But baseball has always been a way that it has defined itself. Audubon High School. You can’t mention Audubon, or Gloucester Catholic, or a litany of other local institutions, without picturing how their names look stitched on a baseball uniform. In front of over 20,000 fans at the College World Series, as Audubon’s Brett Laxton did when he set the NCAA championship strikeout record, or a couple of families at Campbell’s Field on a Tuesday night; baseball has done more than leave an impression on South Jersey. It’s built a legacy of local legends, national acclaim, and hometown kids making good, even if they didn’t make it all the way.

Even in trying and failing, as many have done, to play baseball forever, an enthusiasm grows to pass it along. The majority of us who migrate from the field to the stands still stick around to watch the players who learned how to hit a big league fastball.

“Even if it changes over time and maybe loses its emphasis, baseball, for the longest amount of time, I think, was America’s game,” Borden, a history major in his undergrad days, explains. “It has a cultural connection, and helped America through difficult times, just giving people something else hold onto. Baseball has always been there. Baseball’s been a connection for most of the people, I think, in my generation. I’m getting older, and maybe that connection is going to fade. But from a historical perspective, it will always have an iconic status for what it meant for our country through the last hundred years or more, and I think that’s why it’s important to keep the mementos of that and to understand your place in that context, in that history.”

Like Borden, Haas is the product of a South Jersey upbringing. He played high school baseball, coached at Bishop Eustace for 11 years, and was the head coach at Pennsauken for 16. He is one of the youngest members in the Hot Stovers club right now. He is 68.

“That’s something we’re trying to do, get some younger members,” Haas says. “We send out emails at our coach association, we talk to the members. They say they want to join, but when it comes down to it, they send in dues, but they don’t show up, they don’t help out. We have a big effort going on right now to get all the high school coaches to be members, because we honor all their players. So we’re putting out a letter to the athletic directors to help us with this effort. We don’t ask much.”

The Hot Stovers host an annual golf outing and a yearly banquet to induct new honorees. They have a scholarship program that has provided over $200,000 to local athletes over the years. As youthful interest wanes, the time has come to ask why their mission to maintain South Jersey baseball is so important.

One lesson every adult fan learns is that baseball will never again be what it was to them when they were a kid. You only get one chance to see things through a child’s eyes, and those experiences typically get bubble wrapped in your head and placed gently somewhere in the back.

“I think that players were viewed as heroes, whereas today, maybe you know too much,” suggests Borden. “Players stayed with teams for all of their career, so you really became invested in teams and the guys who played for them year-to-year. Back in the day, baseball played one game on national television during the week, and most of my friends tried to watch that. I think that’s what attracted me to baseball–that and the fact that my father was a big baseball fan. We only had one television and if you wanted to watch anything, you’d watch what your dad watched and my dad watched baseball.”

The challenge is in learning how to transfer what was precious and formative to you onto someone else. You can point at baseball all you want and suggest the appeal of its sluggishly executed strategies and wildly entertaining defensive shifts, but in the end, a key part of sharing baseball is letting prospective fans see it for themselves.

It’s a simple idea made challenging by MLB’s broadcast restrictions; the local nine now have a better chance of being blacked out than broadcast into the ears of English students. Instead of more tired commentary about kids today having their attention spans devoured by their phones, you could give them a place to see what baseball looks like when it’s played in their backyards; a place for parents and coaches to bring young shortstops, backstops, and side-armers, and let them see that not only has baseball been an institution in their hometown since long before they were born, but that their little pocket of baseball has watched greatness emerge from the same infields, outfields, and front lawns in Toms River, Haddonfield, Salem, and Millville on which they play their games. Let them connect the dots between themselves and Mike Trout, the guy their loud uncle would have, until a few days ago, rather have had on the Phillies than Bryce Harper.

Borden believes that CCC is a “county organization, and a service organization.” By giving the South Jersey Hall of Fame a home — a prospective home — he can help strengthen a community with the sport that distracted him from studies as a child, by passing on not just baseball, but the moment he fell in love with it, to anyone who walks through his doors.

“I think it recognizes the history of the sport is made up of contributions made by people,” Borden says. “Some of it comes down to these small town — well, not even just small town — Little League organizations that bred great players. I think South Jersey Baseball has always been incredibly competitive, but I could say that about basketball, wrestling, football; and certainly as an organization that represents the communities in the county, [CCC] would certainly want to honor that. But you know, I think South Jersey sports in general has really strong traditions and really strong histories, and I think it’s important to honor those things and remember those things.”

Everybody involved in this story understands: it’s hard for a stadium like Campbell’s Field, with no major league affiliation and a dwindling audience, to get out of the way of a wrecking ball. When a building comes down, not every memory is going to make it out. The South Jersey Hall of Fame did, and for now, it’s still waiting for its Cooperstown to be built.

“We were looking at the display boards,” Haas says. “They’re leaning up right now against a column in the boiler room at the college. So we were thinking about moving them to a storage facility so they can lie flat on the ground and not warp. Of course, they tell us, they’re looking after all this stuff and assured us that everything will be fine.”

The relentlessness of time makes preservation a desperate act. You can roll up history in bubble wrap and find a boiler room to keep it in, but in the end, that wrecking ball is going to find it. And no wrecking ball swings harder than the pendulum of a clock.

For the Hot Stovers and the South Jersey Baseball Hall of Fame, an ambiguous future is the closest thing to a promise. All they can do is try to keep the glass from cracking on a region’s baseball legacy, so that another generation can scream about a catch at the wall and disrupt Mrs. Kimball’s English class.

“We packed everything up,” Haas says. “Bubble wrapped it, so it’s pretty secure.”

References and Resources

- Interview with Tom Haas, February 6, 2019

- Interview with Don Borden, February 25, 2019

- Jon Gertner, The Idea Factory: Bell Labs and the Great Age of American Innovation

With Rowan University’s growing influence (and overall growth in the Glassboro and South Jersey area), why not look to them to perhaps create a location for this much needed piece of Southern NJ baseball legacy?