The Baseball Story: In The End, Why Must It Begin?

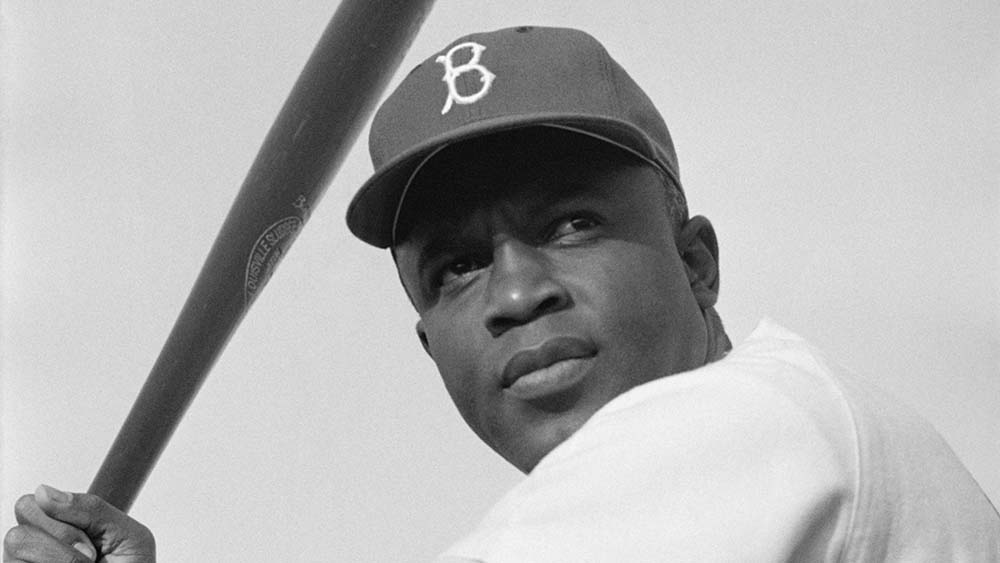

The beginning and end of Jackie Robinson’s career, as portrayed in the movie 42, was something else. (via Library of Congress)

The movie 42, about baseball’s Jackie Robinson, opens with the sound of a typewriter actively clacking. Staccato, emphatic, it is a sound not unlike the one my own keyboard is making now, that of a story being told, of a tale already in progress, situated somewhere between its beginning and its end and in search of its peculiar conclusion. My story differs, perhaps, in that it is also in search of its premise. And what, by definition, is a premise? Well, as Annie Savoy declares at the conclusion of Bull Durham, you could look it up!

I did. Here is the meaning of “premise:” the fundamental concept that drives the plot of a film or other story. So, yeah, unlike the makers of 42, who centered their story on the genuinely heroic exploits of the man who knocked down a sectarian wall and announced, “Here I am — get used to it,” I am ignorant not only of my story’s conclusion but also of its … ummm …. thesis?

I do know why I started this story. Days earlier, I underwent back surgery. The result: less agony, yes, but also a convalescence demanding that I just lounge around. While lounging — again, under doctor’s orders — I decided to use the time wisely, and dare I say productively, by watching a few baseball movies I had recorded. One such movie, Bull Durham, I had seen twice. Four others — 42; A League of Their Own; Sugar; For Love of the Game — I’d not seen. Lastly, I also watched the one-hour documentary Babe Ruth.

And so, prepped for proof of recuperation, primed for a way to convince a skeptical audience that recovery itself had not been starved of a storyline, I searched the cinematic hours for a narrative thread that had tied together these tales. Aside from baseball itself, aside from the sport that accommodated the fictions and nonfictions its storytellers had told, what common themes had marked these half dozen films? In the end, what would be — what will have been? — the fundamental concept?

The films themselves are easily categorized, even if the fundamental concept proves elusive. Consider: Bull Durham and A League of Their Own are rightly classified as comedies; the former has one dude wearing a garter belt, the latter has every woman learning table manners so as not to succumb to “masculinization.” Consider, too: Sugar, about a Dominican ballplayer’s efforts to reach the big leagues while navigating a strange new culture, and A League of Their Own, about the efforts of the women of the All-American Girls’ Professional Baseball League to play ball in a nation that has called upon their Rosie convenience and Riveter dispensability, are fictional accounts of representative biographies, each illustrative of the struggles and triumphs of flesh-and-blood players whose stories, on page or film, have long been subordinate to bigger tales of men like Jackie and Babe.

In short, Miguel “Sugar” Santos and Dottie Hinson don’t exist, but they do.

Babe Ruth and 42, meanwhile, are disparate renderings of true stories. One a documentary and the other a biopic, they shine a light on men already illuminated, already celebrated and fiercely revered, even if one made his name as a boozer and carouser and the other as a teetotaler and family man, in love with his missus as he battled the hatred that had built the wall. As depicted in the film, the love is not incidental to the bigotry he confronts. It is necessary to his conquering of it, vital to his climb. Without Rachel Robinson, the story has shown us, Jackie would not have made the ascent.

Indeed, and lastly, 42 and For Love of the Game can be grouped as love stories. Consider: The real Jackie Robinson and the fictional Billy Chapel share a “passion,” you might cornily call it, not only for the woman who has entered each man’s life but also for the game that has delivered separate versions of the American Dream to the stories they claim as their own. Jackie’s is one of struggle, of a clash against Jim Crow and those old-time baseball cronies who with a “gentlemen’s agreement” had conspired to keep Jackie and his ilk in the Blacks Only parks and out of the Whites Only seats.

Billy’s, too, is one of struggle, not on behalf of some new beginning — not in step with a new frontier that a player like Jackie has manned — but against the same old end: old age, and the time it arrives to finish the athlete’s story.

Born into every beginning, The End is that one inevitable conclusion.

***

The end of Crash Davis, as the Bull Durham audience understands, comes long before The End. Aside from his 21 days in The Show, the hard-bitten catcher is a career minor leaguer, a dozen-plus years in the sticks. Too savvy to have been tossed aside but too untalented to have made it big, Crash had his swan song begotten in a long-ago debut, an early at-bat in some beat-down ballpark where men like him (and Sugar) have dreamed of big league stardom but where the end is conspicuous in the limits of their abilities. He didn’t know it, but we do: Crash was finished as he began.

Still here he is — a day after that garter belt-wearing moron got his big league call-up on the strength of his “million-dollar arm”— striding into the manager’s office to learn that “the organization wants to make a change.” The pain is made public in the blankness of his face, the seasons brushed away as if they’d never started and merely on the air of an utterance: “They wanna bring up some young catcher, some young kid hittin’ .300 at Bluefield.”

The circle of life has been Disneyfied to death, but in baseball it’s still pretty poignant.

Some young kid, too, is Sugar, fresh from a baseball academy in his native republic and now, having learned to order eggs in English, living with his wholesome host family on an Iowa farm and pitching for the Single-A Swing.

Spoiler alert: He isn’t pitching there for long.

For Sugar, the end comes early, too, but in contrast to Crash, who is forced to acknowledge his baseball mortality long after baseball made it abundantly clear, Sugar comes to grips with this sad reality — this real-world coda to an island ideal — as quickly as he once gripped his ticket-to-riches curveball.

The look on his face, a face much younger than Crash’s but now equally seasoned in the proof of bad news, has become a kind of death mask for a man who still breathes. The air at this point is his big poison, what makes his pain physical and deeply felt. The distance — dark, Middle American, thick with the fields that mark every horizon with more grim corn — is not enough to contain his million-mile stare. It regards a future, unlike the past that fueled it with notions of Yankee Stadium and riches for his kin, without the game.

What do we speak of, really, when we speak of the end? For Billy Chapel — again, spoiler alert, but you’ve had two decades to watch For tove of the Game — it comes in storybook triplicate. Call it the Triple Crown of happy endings. He gets the girl, he completes a perfect game and — you guessed it — he goes out on his own terms. Indeed, late in this 40-year-old right-hander’s game against the — you guessed it again — Yankees, Billy sits in the Tigers dugout and writes a simple but essential message on a pristine ball. It is to be given to the Tigers owner, who is selling the team to a callous corporation.

“Tell them I’m through. ‘For Love of the Game.’ Billy Chapel.”

Well, okay. There’s enough corn in that sentiment, and in this dreadful movie, to cover the state of Iowa for the next five decades, but suffice it to say that Billy Chapel, as portrayed by the same Kevin Costner who played Crash Davis all the way to The End, knows how to finish the story he has authored.

Other players, like the women of A League of Their Own, aren’t as fortunate. Positioned as little more than characters in a narrative that others are plotting, they are met with the bleak prospect that the AAGPBL will shut down just as soon as their husbands, boyfriends, and brothers return from the very war that allowed them this opportunity, this chance to leave behind the cow udders at Lukash Dairy and the taxi dancing on the seedy side of New York and instead grab a bat and play some ball in front of paying fans.

“We’re winning the war,” says league founder Walter Harvey to general manager Ira Lowenstein during a late-season ballgame, just as Rockford Peaches pitcher Betty Spaghetti whiffs an opposing batter with the bases loaded in the bottom of the ninth. “(President) Roosevelt himself said that men’s baseball won’t be shut down. We won’t need the girls next year.”

Distressed, Lowenstein replies, “This is what it’s gonna be like in the factories, too, I suppose. ‘The men are back, Rosie, turn in your rivets.’”

Constrained less by gender-role expectations than by the mere fact of their gender as it pertains to professional baseball, the girls play on, all the way to their own World Series, while acknowledging that a Damocletian spike is poised above their hatted heads and primed to end this All-American dream.

And so the end, in this case, is only a specter, weirdly ethereal but tangibly real, like death, not yet arrived — nope, not yet! — but always on the clock.

What do we speak of, really, when we speak of The End? Keep watching. A League of Their Own isn’t finished with its based-on-real-events but fictional tale. In the AAGPBL World Series, kid sis Kit bowls over big sis Dottie to score the winning run for the Racine Belles. For Kit, the end of the game is just the beginning. She will play next season, we soon discover, even if the AAGPBL clock is ticking. For Dottie, by contrast, this really is the end — the end of sing-along road trips and fancy one-hand catches, of game-winning dingers and gunning down runners as they go sliding through the dust. She’s hanging up the shin guards and catcher’s mask, tools not of ignorance but of enlightenment, of those who work where they want.

“You’ll miss it too much,” says Kit to Dottie, postgame.

“Miss it?” scoffs Dottie as they stand in the train station. “Yeah, miss putting on all this gear? Catching a doubleheader in 100-degree heat? Getting slammed into every other day by a baserunner? Think I’m gonna miss that?”

“Yeah!”

No — this, for Dottie, is curtains.

It is the beginning, though, of her authority. She now controls her story. As disappointing as it is to Kit, and to fans of the AAGPBL, Dottie will exercise her postwar liberty by returning to the farm and raising kids with her husband.

And so, a question: How do we really view the end of this film? Like a lot of real-life stories, it moves past one ending to reach another and then another. Kit wins. Dottie loses but wins, too, earning the independence anyone might want. Keep watching. Once begun, narratives intersect and bend back around. Nostalgia now surrenders to the truth of the clock. The league has folded, in both the movie and in the real world, and the girls of AAGPBL are old women now, at least if they are lucky, because some are dead and gone.

Honored here by the Baseball Hall of Fame, they celebrate what they once were: the women of the Girls’ League, not yet given over to that most obstinate author of all: mean old Father Time. With little to see but the wrinkles and little to ponder but the ends they portend, the movie transitions from the faces of the old women to the faces of the young: a black-and-white photo of the Peaches, these same women in earlier incarnations. Nostalgia is reborn as an introduction, an awakening to mortality, the beginning of the you-know-what. And still The End, as positioned by the film, is not yet arrived. The film transitions once more, from a black-and-white photo of the fictional Peaches to color footage of the very real old women of the AAGPBL, now playing ball on a Cooperstown field and refusing to let time stop them.

This, they tell us, is not the end. Is it ever?

***

Like A League of Their Own, the movie 42 and the documentary Babe Ruth must recognize and reconcile the tension between fiction and nonfiction, truth and myth, reality and fairytale endings. Neither of the two protagonists — neither Jackie nor the Babe — is a Billy Chapel, fictional from beginning to end and headed without question to a coda that mortals can only dream of.

And neither is a Sugar or a Crash, figures who, despite their fictional standing, are truly representative of the thousands of nonfictional players who never reached The Show or who remained there just long enough to be quickly forgotten. In short, they are Jackie and Babe, part truth and part myth, and even as the films endeavor to simultaneously integrate and separate the two parts in their middle chapters, they must make peace with each the truth and the legend at their ends. They must find a way, and a place, to conclude the biographies without sacrificing either the man or the myth he still inhabits.

A player’s tale will typically end at one of three points: at game’s end, at career’s end, or at life’s end. Call them the Triple Crown categories of Pastime storytelling. More, the story must make the other two ends implicit in the conclusion it singles out. In 42, the end has its onset in the first inning of the Dodgers-Pirates game on September 17, 1947. With a win, the Dodgers will clinch the NL pennant and advance to the World Series to face the Yankees. Jackie, at the center of attention, is facing Pirates starter Fritz Ostermueller in the top of the frame, just a couple of major leaguers battling it out at a distance of 60 feet six inches. At this point, though, Jackie is as mythic as he is mortal. While all the usual bigots have subjected him to all the usual epithets, others have called him “superhuman.” Dodgers GM Branch Rickey has compared the man to Christ. Jackie, in a word, is messianic.

Is it a ridiculous designation, or is it fitting? He comes strictly from flesh, always flawed, and his pioneering year in the majors hasn’t been without human emotion, a Cleansing Of The Temple-type anger he has felt in the face of hatred. In his first at-bat, against Ostermueller, he grounds to third baseman Frankie Gustine, who gets the out by throwing to first baseman Hank “The Hebrew Hammer” Greenberg, a man likewise subjected to racist abuse but a man who, messianically, returned to baseball just two years earlier after serving 47 months at war, the longest military tenure of any player in history. This isn’t fiction. Even if unexplored in the film, this is fact.

Also fact is that in the fourth inning, still facing Fritz, Jackie hits a 3-0 pitch over the left-field fence for a go-ahead homer, putting the Dodgers up 1-0 en route to their 4-2 win. (Okay, so it’s not fact. In reality, Jackie hit a 2-2 pitch for the go-ahead homer, a truth that attests to the added drama that creative license can yield.) Half a century later, sabermetrics —that most factual of reckonings — would cite the home run as the game’s most important play, boosting Brooklyn’s chances of advancing to the World Series by 12 percent.

It is at this point, with Jackie heading home, that the film is reaching its end.

“Home, sweet home” is how sportswriter Wendell Davis puts it, clacking away on his typewriter — the first laptop — as he sits among clapping fans.

After Jackie rounds third base, the movie jumps to collateral scenes. Here is Rachel, pushing the baby carriage along a sunny Brooklyn street while neighbors celebrate the home run and the win … and the larger victory. Here are teammates clapping, fans clapping; Red Barber clapping. Is it to show that other tales are always running crossways to the one to which we are audience? Here again is Jackie, fast-forwarded to the game’s aftermath and seeing on a city street the evening edition of The New York Times. Headline: HAIL TO THOSE BROOKLYN BUMS. And here once more is Jackie, doubly rendered, arriving at home to embrace his wife … and arriving at home plate.

For the man 42, and for the movie 42, it is the perfect ending. Implicit are the facts we have come to acknowledge: his final at-bat, a whiff to end the 1956 World Series; his retirement, an on-his-own-terms departure after the Dodgers traded him to the rival Giants; and his death, at 53, in 1972.

Implicit, too, are the glories that came before: Jackie has opened the gate for Don Newcombe, Roy Campanella and other black players. He has earned recognition as Rookie of the Year and MVP and has reached the Hall of Fame. He’s had his number — that distinguished 42 — retired. And now, on one day each season, every player in the major leagues makes it his own.

What the ending doesn’t show us, what it conveniently leaves out, is that the Dodgers go on to lose that 1947 World Series, in seven games, to the Yanks.

Nope, that’s no way to end a story. Just ask Billy Chapel.

You can’t conclude a story, fictional or nonfictional, by losing to the Yanks.

The Yanks — those usual, damnable Yanks —- have remained the franchise synonymous with the Babe Ruth mythos. Consider: He delivered his famed Called Shot, we are told, in those illustrious pinstripes. The Yanks are also synonymous with his truth. The Babe hit 60 homers in 1927.

You could look it up!

The Yanks were not, however, the team with which he finished his career. Whatever the legend, the facts are these: In 1935, after the Bambino had rocked a 1.167 OPS across his 21 seasons in pinstripes, Yankees owner Jacob Ruppert, desperate to ditch his aging star, forged a secret deal with the struggling Braves to send the Bambino packing. In efforts to turn Ruth into a gate attraction, Boston would give him the titles of assistant manager and vice president. Soon after, the Yankees assigned the Babe’s famed No. 3 to second-year outfielder George Selkirk and used his locker to store firewood.

Nope, this was no way to end a story. This was no Hollywood ending, for real. But it happened, as the documentary makes perfectly plain. Ruth would go on to hit six home runs in 28 games for the Braves that season before calling it a career in late May, a once-heroic figure now saddled with the sort of ordinariness that only other men, lesser men, had known.

Self-evident in Babe Ruth, then, is the balance of Babe Ruth as fiction and fact. “He was celebrated for the mythical figure he was,” the documentary has told its contemporary audience, “who at the same time was flesh-and-blood.”

Early on, we see his spring-loaded swing, all potential energy at once unleashed and “wrecking the whole afternoon with one swipe.” We see the ball arcing to heights and distances never before known to the Pastime.

“No Hollywood writer would have dared invent somebody like this,” says one historian. “This was science fiction.”

Likewise watching, we see the mighty body and those little mincing steps, so contradictory but perhaps befitting a man whose “personality was a paradox, forged by two competing forces” — those of goodness and iniquity alike.

We see it again and again: the mighty wallop, the mincing trot.

Is this for real?

It is, in fact, Ruthian.

“It’s like he was created for this role he was given,” says another longtime watcher, “and he played it to the hilt.”

We learn, too, about the boozing and carousing. He left his wife and child. We hear about the Great Bellyache of 1923, aka VD. Near the end we see the body, once full of strength and life and hot dogs and beer, brought low by a history of high living and a future in the grip of disease, the cancer that will bring about his death, like Jackie Robinson’s, at a mere 53. We see, in addition, the famous photo of old No. 3, his back curved with burden. The film won’t end with a game-winning wallop, or with mincing steps toward home. It will end with these images: an open casket, little kids crying, and grown man making the sign of the cross. Implicit, you could say, is No. 60.

It will end, as well, with conclusive words.

“Babe Ruth will never be gone. He’s still here. He’s always here.”

***

Still here, too, are Sugar and Crash. Unlike the Babe, their legacies won’t find enshrinement. But, in a more personal space, each has outlasted his ouster to fashion a fresh start. Following his release from the Bulls, Crash catches on with the Asheville Tourists and, on a sunny day at the yard, bashes his 247th minor league home run, good for an all-time record. Following his own departure from the Swing, Sugar catches on with a furniture maker for money and with an amateur team for fun, playing ball on a sandlot field near Yankee Stadium and all the fairytales it once upon a time invited.

Now, with his record in the books, Crash returns to Durham and makes his way to Annie Savoy’s porch. There on a swing, he tells her he’s done.

“I quit,” he says. “Hit my dinger and hung ‘em up.”

And yet for Crash, this is not The End. It’s near but not yet arrived. There might be an opening, you see, for a managerial job next spring.

And here, in our conclusion, we arrive at what must be the premise.

“Another Opening Day,” says Branch Rickey in 42, grinning expectantly as he watches his Dodgers take the field for their first game. “All future, no past.”

His assistant nods. “It’s a blank page, sir.”

John,

That was sizzling prose from a deep place. Back-surgery brought out a jewel from your fingers; I hope your funny-bone was undisturbed by the recent cutting.

Taking a tangent off your Babe-in-film allusion, I’d like to foul-off a pitch offered by the assorted Babe Ruth documentaries. Historians, filmmakers and myth-makers frequently miss his after-baseball stature in cancer-research. The Babe’s prominence in and proximity to NYC made him an important figure in the clinical trials of and ethics of the post-WWII technology of chemotherapy.

“It went from mice to Babe Ruth”

https://www.popsci.com/babe-ruth-cancer-treatment

87 Cards:

Thank you for the kind words. Write a piece like this, it’s usually to an audience of none, so I’m glad somebody took the time to read it. Much obliged.

As for the funny bone/surgery relationship, well, the good doc more or less restored it. The days preceding surgery were little but a study in excruciating, stupefying pain. Even for a wordy wordy wordy writer, there are no words for that kind of agony. Needless to say, it’s hard to toss off sparkling one-liners while sprawled motionless on the bed and screaming for six hours straight.

As for Ruth: Man, thanks so much for the info and the link. That’s a fascinating and remarkable story. Who knew?! The Babe did far more for humanity than sock the bejeebers out of baseballs.

Cheers!