Card Corner: One Man’s Favorites

(via Michelle Jay)

In 2013, the Hall of Fame closed its baseball card exhibit, replacing it with an exhibit featuring photos taken by Cuban photographer Fernando Salas. After the removal of the longstanding card display, visitors who asked were told the exhibit had grown stale and out of date, but that it would likely be replaced by a newer card exhibit in the coming years.

That day is about to come. On May 25, the Hall will debut “Shoebox Treasures,” a comprehensive exhibit about the history of baseball cards. The exhibit will feature many of the most valuable and intriguing cards from the Hall’s collection, which numbers over 200,000 in total. “Shoebox Treasures” will explore the origins of baseball cards in the 1800s, the rise of tobacco cards, the significance of the Honus Wagner T206 card, and the roles of industry pioneers like Sy Berger, Woody Gelman, Jefferson Burdick, Doug McWilliams, and others who have contributed to the rich history of the hobby. The exhibit will also include a number of drawers that will be packed with a wide selection of cards.

For me, the exhibit carries a personal connection, in two different ways. While I am not a curator, I have served on the committee entrusted with overseeing the card project. That has given me the chance to offer my thoughts on the kinds of stories this new exhibit should tell. Second, as anyone who has read my Hardball Times articles can attest, baseball cards have long been my hobby, ever since I made my first trek to Gillard’s Stationery Store to purchase my first pack in the spring of 1972.

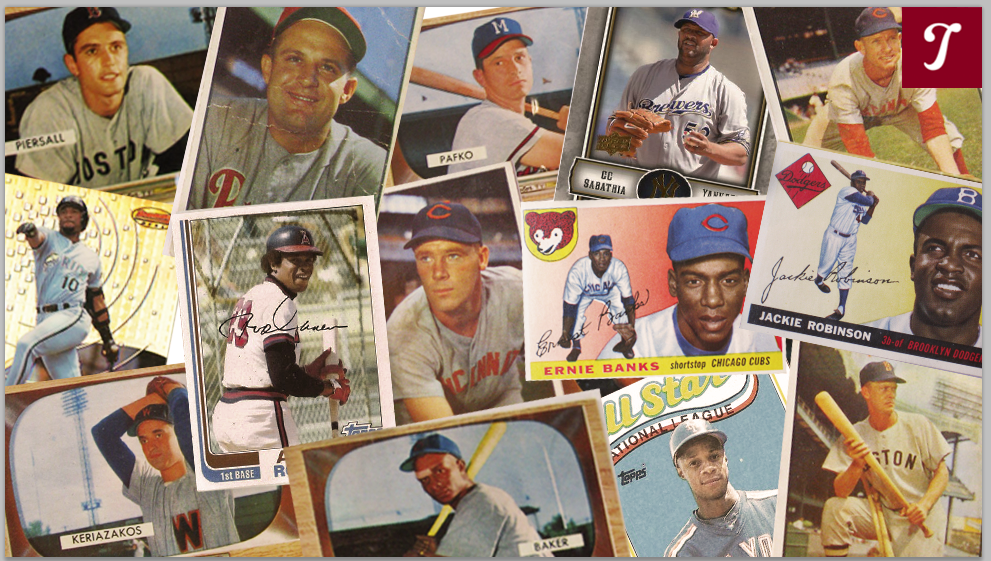

To recognize the exhibit, now seems like the right time to present a sampling of some of my favorite cards I’ve collected over the years. I do not own the T206 Wagner, the ’52 Mickey Mantle, or the rookie cards of Jackie Robinson and Roberto Clemente. Instead, I’ll concentrate on what I do have, a smattering of personal favorites from the 1960s, ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s.

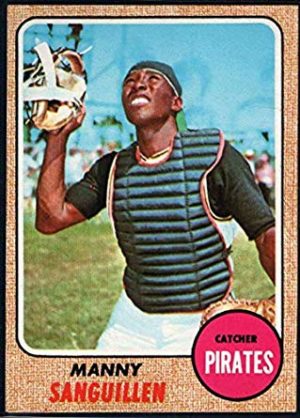

Manny Sanguillen—1968 Topps: Back in the ‘60s, the word “groovy” was a way of describing something excellent, or desirable, or just cool. So when I look at Manny Sanguillen’s rookie card from 1968 Topps, I think, “This thing is groovy.”

There is plenty to like. First, the weather backdrop for the card appears to be ideal. Taken at what looks to be the Pittsburgh Pirates’ spring training site in Bradenton, Florida, the photo gives us the brightest of blue skies and a glaring sun. After a long winter, it’s always refreshing to look at a baseball card photograph taken on a picture-perfect day.

We see Sanguillen in his full catching gear, complete with chest protector and catcher’s mitt. (The cropping of the photo makes it impossible to determine if he’s sporting shin guards, too.) Sanguillen is also wearing his cap backwards, as all catchers do when they take their places behind the plate. I always like to see catchers wearing their gear on their cards. It gives them a look of readiness, as if they’re fully prepared to play a game and not just casually killing time during a lull in a spring training workout.

Clearly, the photo doesn’t depict actual game action, but Sanguillen is doing his best to recreate the situation under the setting of spring training. Holding his mask in his bare hand, he squints as he looks skyward into the intense spring sun, pretending to track an imaginary pop-up. It’s a pretty realistic pose, a good acting job from a player who has been asked to simulate a defensive position.

The card is also enhanced by the depiction of Sanguillen, a positive and vibrant personality who became one of the game’s most likable players in the 1970s. At the time of the card’s release, Sanguillen was coming off a 30-game debut season that saw him hit .270. Somewhat surprisingly, he wouldn’t make the Pirates’ roster in 1968 but would return to Pittsburgh in 1969, beginning a stretch as the team’s unquestioned first-string catcher. He would appear on numerous Topps cards over the next decade, but perhaps none so memorably as his rookie card of 1968.

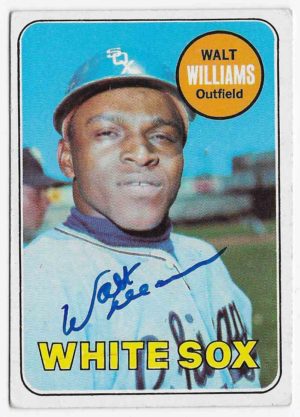

Walt Williams—1969 Topps: I first became aware of this card when I read the seminal book, The Great American Baseball Card Flipping Trading and Bubble Gum Book. (It’s a tongue-twisting title, but the book is exceptional for its sense of humor and its insights into baseball cards of the ‘50s and ‘60s.) Authors Brendan C. Boyd and Fred Harris devote some time to outfielder Walt Williams, a human fire hydrant who was all of 5-foot-6, with broad shoulders, a thin waist, a prominent chin, and a completely indiscernible neck.

As is quite evident on his 1969 Topps card, Williams’ head appeared to rest directly on his collarbone. Williams’ neck was so short that he was called “No Neck,” a moniker given to him by catcher John Bateman, one of his early teammates with the Houston Colt .45s.

In the early 1970s, young fans like me almost always referred to Williams as No Neck Williams; we rarely called him Walt. Yet, Topps never featured Williams’ nickname on any of his cards. That was probably fine by Williams, who bristled at being called No Neck before eventually coming to accept it.

Nickname or not, Williams was a fun player. A contact hitter who rarely struck out, he ran well and could play all three outfield positions, in addition to second base. He also had a voracious appetite, he was known to sometimes polish off more than 20 hamburgers from Burger King in a single sitting.

The man could eat in addition to serving as a distinctive model for some memorable baseball cards.

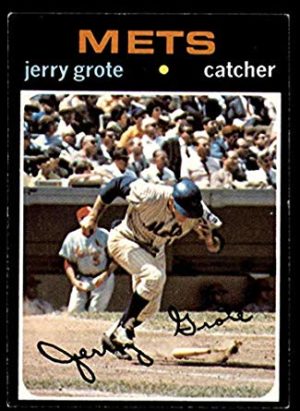

Jerry Grote—1971 Topps: In 1971, Topps did something it had never done before: showcase players in full-color action photography from actual games. In total, Topps used action shots of 52 players, making the ’71 set far more exciting and dynamic than many of its predecessors.

In depicting New York Mets catcher Jerry Grote, Topps included a photo from a 1970 game at Shea Stadium between the Mets and the St. Louis Cardinals. How do we know the Cardinals are providing the opposition? In the dugout, we see a Cardinals uniform (No. 5) worn by veteran coach Dick Sisler, the son of Hall of Famer George Sisler.

Grote is seen busting his way out of the right-handed batter’s box moments after making contact with a pitch. He’s running full force, head down and arms pumping, as though this were Game Seven of the World Series, not some forgotten game from the middle of the season.

This card runs counter to the habits we witness in today’s game, where all too often players can be seen not running hard on pop-ups or grounders. No, the hard-nosed Grote was old school all the way.

Grote’s way worked, as he maximized his limited physical skills. Though he didn’t have much talent as a major league hitter, his hustle, determination, and strong defensive skills allowed him to remain a front line catcher for roughly a decade. He helped two different Mets teams reach the World Series.

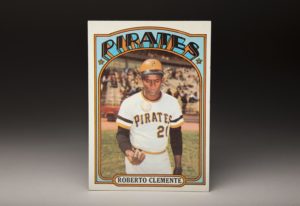

Roberto Clemente—1972 Topps: When I first picked up this card, I noticed the darkness of the background; it seemed the photo was taken on a particularly cloudy day at Shea Stadium, sometime before a game between the Pirates and Mets. Later, I came to realize a far more intriguing part of the card: the strange presence of a ball in mid-air, one that had subtly blended into the color of Clemente’s Pittsburgh uniform, just above the Pirates name. It struck me then that Clemente had actually tossed the ball into the air when the Topps photographer took his picture. The positioning of his right hand, with the palm up and the fingers extended, confirms that Clemente has just released the ball from his grip.

This card just smacks of Clemente’s coolness. He seems oblivious to the presence of the photographer. He also doesn’t seem too worried about dropping the ball as it descends. Was this shot planned? There’s no way to know for sure if Clemente and the photographer staged this pose or if the photographer just happened to catch him at the moment where the ball was in mid-air.

I’m probably being naïve about this, but I’d like to think it was the latter, a spontaneous moment that just makes Clemente seem that much cooler to us. Either way, it’s still a nifty shot, one that is different from most of the other posed shots of this era.

The card also reminds us that Clemente’s career and life were coming to an end. Along with his ’72 “In Action” card, this was the final one that Topps issued while he was still alive. His 1973 card would come out after his death, a final tribute to this Hall of Fame talent and heroic humanitarian.

As much as I love the ’73 card, which features a beautiful action photograph from a spring training game, I think I’ve come to like his ’72 card a little bit more. When I look at the ’72 card, I’m reminded of what Commissioner Bowie Kuhn, a great admirer of Clemente, once said about the player dubbed “The Great One.” “He had about him,” said Kuhn, “a touch of royalty.”

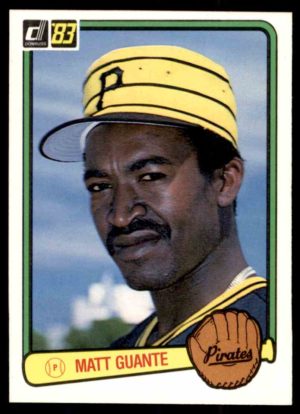

Cecilio Guante—1983 Donruss: The end of the Topps monopoly brought some variety to card collecting, as Donruss and Fleer entered the fray in 1981. After some growing pains, the two rival companies began showing improvement with their 1983 card designs, even if they continued to produce their fair share of error cards. One of my favorite sets from the era is ’83 Donruss, which featured a smooth design and ultra-clear photography. The set included this card, showcasing a player named “Matt Guante.”

It’s a nice-looking card, even if Guante appears to be sneering at the photographer. More than the sneer, what jumps out at you is the name of the player: Matt Guante. There was no player by that name in 1982 or ’83. There was, however, a pitcher named Cecilio Guante, a hard-throwing right-hander with a nasty delivery who eventually became an effective middle reliever for the Pittsburgh Pirates and New York Yankees.

So how did it happen that Donruss came to list the colorful Guante as Matt?

This case of mistaken identity would have been more understandable if Donruss had placed a Latino-sounding name, like “Carlos” or “Cirilo” or “Claudio,” on the card. Matt doesn’t sound anything like Cecilio. It just doesn’t fit.

One theory seems plausible. A fellow collector told me that he believed that someone at Donruss had confused Cecilio Guante with Matt Galante, who was a coach for the Houston Astros back in the 1980s. Galante and Guante sound alike, especially when you say them quickly.

At first this seemed like a reasonable guess, but Galante didn’t start coaching for the Astros until 1985. The mystery remains, making this card even more lovable to me.

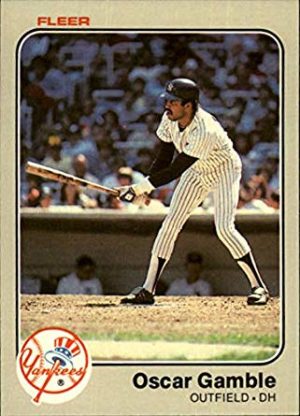

Oscar Gamble—1983 Fleer: While most fans and collectors gravitate toward his airbrushed 1976 Topps Traded card and the splendor of his gargantuan Afro, my favorite card of Oscar Gamble comes from a set released seven years later. It is part of one of the early sets put out by the Fleer Company, an underrated selection that featured team logos in the corner and a gray border that was reminiscent of what Topps did with its 1970 set.

In this case, we see a nice action shot that was photographed at Yankee Stadium sometime in 1982. More than any of his other cards, the ’83 card captures Gamble’s unique batting stance with an unusually deep crouch. We can also see Gamble waggling the bat, a timing mechanism that he used in the moments before each pitch. Between the waggle and the crouch, this is exactly how I remember Gamble, a player I saw often during his two stints with the Yankees. By then, the large Afro was gone, sacrificed because of the grooming rules set forth by the Yankees. But the distinctive batting stance remained.

The card also reminds me of how dangerous a hitter Gamble could be, particularly when facing a right-hander at Yankee Stadium. The way Gamble set himself up in the batter’s box, his body looked like it was pointing directly toward the right field bleachers, a favorite landing spot for his home runs. If a right-hander made a mistake on the inner half of the plate, Gamble seemed almost destined to deliver a deep fly ball into the short porch at the Stadium.

In addition to his power, Gamble’s personality made him a likable player. He was outgoing, quotable, and full of humor, the kind of player the Yankees needed in a clubhouse that was often divided by conflict. Any card of Gamble is a good one, but ’83 Fleer remains at the top of the list for me.

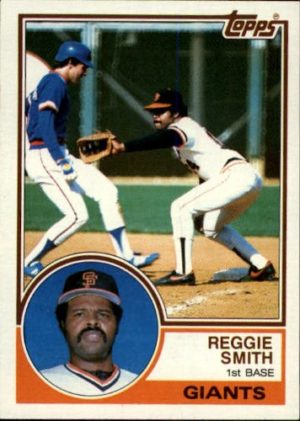

Reggie Smith—1983 Topps: Not only did the entrance of Donruss and Fleer create more variety and choice, but it also forced Topps to improve its product. One of the early examples came in 1983, when Topps issued a set that featured two images on the face of each card. Topps also increased the frequency of action shots, while greatly upgrading the design quality that had reached a low point in 1982.

One of the best cards from 1983 gave us two stars in action. It’s the Reggie Smith card, the final card Topps issued for the underrated slugger, who would soon move on to the Japanese Leagues. As seen in a 1982 game, Smith is taking a throw at first base, while a skinny Chicago Cubs baserunner is casually making his way back to the bag. At the time, only Cubs diehards might have taken note of the baserunner’s identity. But now we no longer take his presence for granted. That runner is Hall of Famer Ryne Sandberg, who was playing his first full season for the Cubs.

Sandberg’s presence on the Smith card doesn’t do much to change its value, but it’s always fun when star players make cameos on cards belonging to other players. The Smith/Sandberg duo is reminiscent of Bobby Bonds’ 1973 card, which he shares with Hall of Famer Willie Stargell, in another photo taken at Candlestick Park.

Two stars for the price of one.

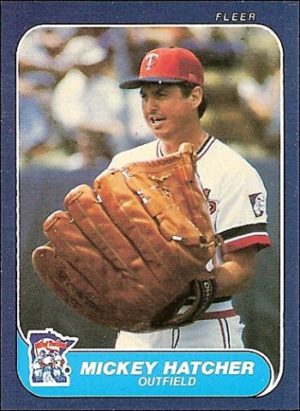

Mickey Hatcher—1986 Fleer: Never has a player looked so ridiculous on a card as Mickey Hatcher does on his 1986 Fleer card. The outlandish size of the glove, which appears to be the diameter of two frying pans, coupled with Hatcher’s mischievous expression, make this a card classic.

The card also epitomizes Hatcher’s status as one of the wackiest major league players of the 1980s. In fact, someone ran a poll in the middle of the decade, asking major leaguers to name the zaniest of their brethren. Hatcher finished first, beating out other eccentrics like the late Joaquin Andujar, Greg “Moon Man” Minton, and Steve “Rainbow” Trout.

There is an intriguing backstory behind this card. No, Hatcher did not use this glove in an actual game. During spring training in 1985, a glove company visited the Minnesota Twins’ camp in Orlando. Hatcher saw the glove lying on the ground and decided to put it to good use. “I picked it up and the card guy just happened to shoot it when I was out there playing for fun,” Hatcher told ESPN.com. “I said, ‘Get a picture of me with this glove because I need all the help I can get.’”

Apparently, the glove company loved the free publicity that Hatcher was giving the glove, so a representative let Hatcher keep it, hoping that the Twins’ utility man would bring it around to all of the American League sites. Hatcher did just that, lugging the glove around on Twins road trips. The glove became a ready-made prop, something that Hatcher could unleash on teammates and fans at any time.

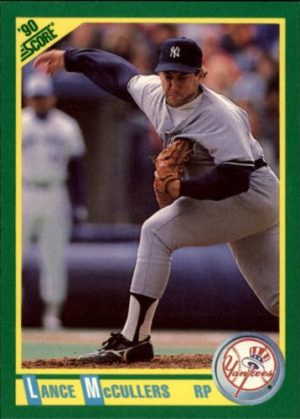

Lance McCullers—1990 Score: The Score Company has become a forgotten part of baseball card lore. It put out sets from 1988 to 1998, with a heavy emphasis on action shots and colorful borders. As I look back on Score’s early cards, they seem rather gaudy to me, but the 1990 set stands out for being well done, with its variety of colored borders. The set includes a memorable entry for Lance McCullers, the father of the Houston Astros pitcher and a good relief pitcher in his own day. This card may have provided a foreshadowing of the elder McCullers’ career.

When I first saw the McCullers card, I did a double take. The finish of McCullers’ delivery, as seen in a game against the Toronto Blue Jays, looks painful. While I am not an expert on pitchers’ mechanics, I can tell that this motion didn’t exactly come out of Pitching 101. At the end of his release, McCullers’ head is turned completely toward first base. The right-hander is also sporting a discernible grimace, which only adds to the feelings of discomfort.

When healthy, he was a major talent, a right-hander who was built like a bull and threw a live, moving fastball. At one point, I thought he would become a dominating closer. Yet, I don’t I remember him finishing his pitching motion so awkwardly. Still, the camera doesn’t lie. The 1990 Score card reveals an obvious imperfection in his delivery. So do a few other McCullers cards that were produced in the early ‘90s.

In this case, the card seems to be revealing a lot. By 1990, McCullers was starting to suffer from arm problems, which limited him to 20 appearances that summer. He then missed all of 1991 with arm trouble, before making a brief comeback in 1992. That season, he made five relief appearances for the Texas Rangers, walking eight batters in five innings. In June, the Rangers released McCullers, ending his career. At the age of 28, McCullers was done, his career essentially halted by arm problems.

While I can’t prove that McCullers’ awkward delivery led directly to an arm injury, his 1990 Score card reminds us that the human arm was probably not meant to pitch a baseball for any length of time.

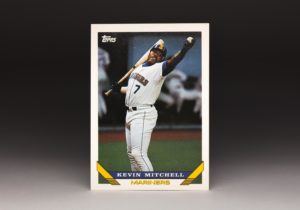

Kevin Mitchell—1993 Topps: Kevin Mitchell’s days as a Seattle Mariner might not be memorable—he played only one season for the team—but his 1993 card will always stand out for me. I’m not exactly sure what Mitchell is doing on this card, which was photographed at the old Kingdome. Perhaps he is preparing to hit a fungo to one of his teammates. Yet, he is not using a fungo bat. He is also standing in an odd position, leaning so far back that he appears on the verge of falling over.

Mitchell seems to be making an exaggerated show of things, as he holds a ball in his left hand, his arm extended as if he’s gesturing to the outfield. Perhaps Mitchell is calling his shot, à la Babe Ruth.

Whatever he is doing, he is likely having fun doing it. He was known as “Boogie Bear” during his playing days, a tribute to his free-styling personality and behavior. He had a distinct personal style, including wearing crocodile-skin combat boots, which were said to cost nearly $2,000. He also collected cars and other vehicles. At one point, he reportedly owned a 1964 Chevy convertible, a Humvee, two dune buggies, a pair of pickup trucks, two trailers, and a fleet of 11 all-terrain vehicles.

Mitchell could have used those vehicles to relocate in 1993. He did not play at all for the Mariners, who’d traded him to the Cincinnati Reds the previous November for Norm Charlton. Even at 31, Mitchell could still hit. He would bat .341 with 19 home runs for the Reds in ’93. No, his trouble was staying on the field. Injuries limited him to 93 games that season, and 95 the following summer. In 1996, he missed the entire season. By ’98, he was out of the big leagues.

If not for injuries, Mitchell might have made the Hall of Fame. The man could hit. Put a bat in his hands, and he was ready to have some fun, just like he did on his 1993 Topps card.

These 10 cards represent the tiniest of fractions of a collection that has been assembled over a nearly 50-years stretch. Will any of these cards be featured in the new Shoebox Treasures exhibit at the Hall? I cannot say for sure. That is ultimately up to the curators. But there will be thousands of cards filling the drawers of the exhibit, so the chances are pretty good.

I have a feeling that there will be something for everyone.

I remember watching an NBC game of the week in 1967 and Curt Gowdy referred to Williams as “No Neck” Williams as if that was his real name. Note the backwards cap on Sanguillen. Back then, catchers did not look like they were auditioning for a gig on The Empire Strikes Back.

I love this series and look forward to every post. Spot-on about Oscar Gamble in the old Stadium — out of all hitters with 600 PAs there, he was 6th in OPS, 4th in slugging (ahead of Mantle!), and trailed only Ruth in isolated power. And what a great stance!

I thoroughly enjoyed reading this article. Bravo!

The action cards from the early 70s sets seem so much better to me than what we see today. There’s something so much more real in them. Is it only me?

great post. i like it. feeling great when reading your post

outlook entrar

Late to the party, but the Kevin Mitchell card should be paying homage to the barehanded snare he made near the wall in a live game, https://youtu.be/4u0MzrYPm4w…Mitchell was kind enough to sign this card for me.