The Inclusive Legacy of Backyard Baseball

While not the most realistic baseball simulator, Backyard Baseball holds a special place in many hearts. (via Jason Scott)

Sports video games wouldn’t be much of anything without their athletes. The closest we could otherwise get to the genre that has captivated fans for decades might be the PC classic Hot Dog Stand: The Works, a game with no actual athletic competition (but one that does feature an iconic theme song). Fortunately, that is not a world we have to live in. The most polished and popular games of the 21st century have the luxury of licensing, and therefore feature increasingly impressive recreations of the world’s best professional athletes, and do so to great effect. But despite the large shadow these games cast, most of the world’s baseball playing is not done at the professional level; some games account for this in their design.

For most people, baseball begins as a kid’s game, and that is exactly what Humongous Entertainment’s 1997 release Backyard Baseball aimed to capture with its 30-character cast of children. Over two dozen sequels, which branch into various sports, have ensured the game became a cultural touchstone for its generation of players. What isn’t immediately obvious even to the most devoted fans is that the original cast exudes a level of diversity, inclusion, and equality that, even two decades after the game’s initial release, remains inexplicably rare in the world of sports media.

One way this is achieved is through the races of the available players. For perhaps the first time in the (shockingly lengthy) history of baseball video games, white players do not account for a majority of the roster. Though the 13 available white players (43.3 percent of the total) still constitute a group larger than that of any other race, Humongous Entertainment’s decision to include 17 total players of color is one that not only distinguishes the game from its sports-centric peers, but from baseball’s most prominent platform: Major League Baseball.

According to The Institute for Diversity and Ethics in Sports, major league baseball’s player population was 58 percent white in 1997, the year of the game’s release and was just a tick more so (59 percent) in 2018. Making characters of color the majority provides a platform for unparalleled representation within the context of the sport, and the game does not waste it. Each character has a skin tone that is unique t (save for the five pairs of siblings), and this spectrum includes a variety of Black, Latinx, and Asian players.

That this level of racial diversity may not be the game’s most inclusive attribute is perhaps the most impressive thing about it. No women have suited up for a major league team as of 2019 and even fictional representations are mostly lacking, with the exception of the fantastic Ginny Baker. But the Backyard cast includes 15 female players alongside its 15 male players, a 50-50 split that seems almost too good to be true but isn’t.

Baseball’s history is inextricable from the women who have played and continue to play it professionally around the world, yet popular culture has almost nothing to show for it. A quick look at a list of baseball films is all the evidence one needs to get a lay of the land. As great as 1992’s A League of Their Own is, it should be a movie about women’s baseball by now, 27 years later, instead of the movie about women’s baseball. Pitch made a valiant effort (and may get to make another) to make an impact, but ultimately couldn’t quite find its footing in the national discourse. Every effort matters in the fight against sexism, and that a children’s computer game was one of so few works to make one is both a testament to Humongous Entertainment and an indictment of American pop culture at large.

In the past few years, the fight against discrimination in pop culture has gained unprecedented prominence in the public discourse, but it has been taking place for the entirety of the industry’s existence. The use of words like “racism” and “sexism” in these conversations make some people (who are likely male or white or both) quite uncomfortable, but the words and discomfort alike are necessary to communicate the gravity of the situation. And what is actually at stake here?

In 2016, Michelle Obama told Variety that “for so many people, television and movies may be the only way they understand people who aren’t like them.” Her point is clear: Pop culture can provide exposure to other cultures that one may otherwise never have. But as much as it can teach people how others can be different, it also has the power to show cross-cultural similarities, a power Backyard Baseball utilizes to great effect.

Achmed Khan has always been a personal favorite, in part because he absolutely mashed but also because I liked his theme music, which resembled the kind of rock music my dad and I liked to listen to. I’m a white man who grew up in a mostly white town. I hadn’t actually met anyone named Achmed or Khan, but because of this game and this character and his brother Amir, I knew when the time came (and it did, in my high school days) that other than some aspects of appearance, we were both people capable of sharing all of the same interests. Backyard Baseball alone did not make me a more racially tolerant person, but it absolutely planted seeds of inclusion that most of society and pop culture fail to. Lessons like that, especially for an audience of children, are invaluable.

With all of that said, Backyard Baseball is still a game, and its characters athletes. They do not exist simply to be observed, but to play ball. Just as their identities vary, so too do their on-field talents. The characters’ skill levels exist on a spectrum that each and every one of them is likely to be acutely aware of. To this day, a year after collecting my undergraduate degree, I can still recall who the most athletic kids were in my elementary school gym classes and the burning desire I had to beat them at something, anything.

I like to think I’m not alone in that, either. There is a reason Jess’ obsession with racing (and eventual loss to Leslie) in Katherine Paterson’s Bridge to Terabithia has resonated with so many readers over the years. There are few opportunities for social status before you hit a double-digit age, but athletic ability is definitely one. A perceived on-field hierarchy is inevitable, for better or worse, and whether the game is being played at Tin Can Alley or Parks Department Field No. 2, Backyard Baseball is no exception.

My ability to recall the premier athletes of the game, as well as those from my second-grade class (shout-out to Joey, whose grace in victory now seems like a stereotype-buster in its own right) reminded me of the fact that some characters are, in fact, better than others. However, whether or not the demographic diversity of the roster extended to actual baseball performance was not something I could recall (or claim to have ever known), so I dove into the numbers in an attempt to find out.

MLB The Show and Out of the Park Baseball impress year after year with their astonishingly intricate rating systems that ensure their simulations can match the complexity of the real-life baseball we know and love. In comparison to those constantly adapting and evolving systems, the simplicity of Backyard Baseball is almost as jarring as it is endearing. Each player is rated in four skills (batting, running, pitching, and fielding) on a scale of one to four baseballs, the ultimate unit of measurement. For the sake of this project, these baseballs will be referred to as skill points.

In total, there are 120 individual skill ratings (four for each player) and 311 overall skill points. Ninety-one of the 120 skill ratings (75.8 percent) are of either the three-skill point (49, 40.8 percent) or two-skill point (42, 35 percent) variety. As a result, most characters are extremely close in overall skill points: Eighteen of 30 (60 percent) have 10 or 11 total. The one-skill point ratings are the rarest (12 out of 120, 10 percent), with the four-skill point ratings not far behind at 14.2 percent (17 out of 120). Such a skill point distribution gives life to a deep middle tier at the cost of thinner top and bottom tiers, which makes perfect sense in the context of this game. Every player is meant to be usable, and given that no player has less than eight total skill points, they all are. But how evenly are these points distributed along race and gender lines?

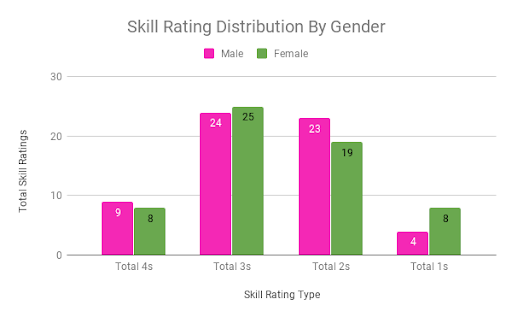

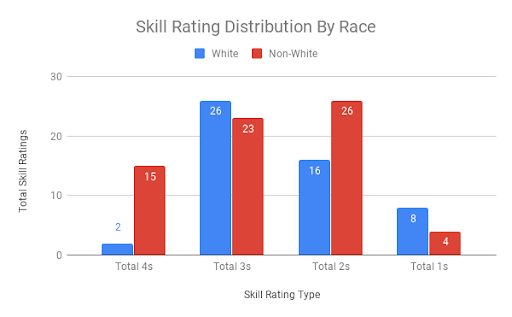

First, I opted to determine how many skill ratings of one to four were assigned to female players compared to male players and players of color compared to white players. Here are a couple of charts that display those results:

The most drastic split between the two can be found in the four skill-point category. While the 17 ratings are divided as evenly as possible by gender with a slight 9-8 edge for the male players, a whopping 15 belong to players of color to just two for white players (one in running for legendary speedster Pete Wheeler and the other for ace pitcher Angela Delvecchio). The only other double-digit discrepancy in either the race or gender rating distribution is in the two-skill point ratings, where players of color have 10 more, though in that case the fewer ratings the better. The four skill-point difference is the driving force behind the slight edge in average skill points per rating for the players of color (2.72) have over the white players (2.42), at least in terms of average skill points per rating.

The gender splits are a lot more balanced overall, but they do favor the male players. Eight of the 12 one skill-point ratings belong to female players and the other four to male players in a category it actually hurts to lead in. The male players get the worse end of the two-skill point ratings with 23 to the 19 of the female players, the three-point ones are 25-24 in favor of the females players, and the four-skill point ratings are split 9-8 in favor of the males players. While there is no strict equality here, there is most certainly competitive balance, though it would have been neat to see female players be given a slight edge if only so the difference could not be confused for a gender-based slight.

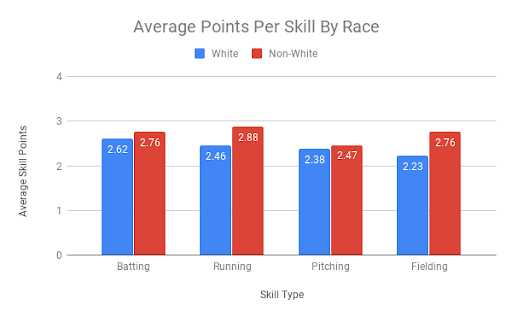

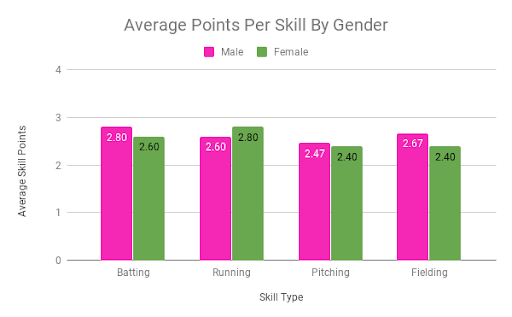

Splitting up the points by skill provides an alternate and complementary perspective, one that sheds even more light on the division of talent among these groups. The largest sum for any of the four is 81, which batting and running share, followed by 76 for fielding and 73 for pitching. In the charts below, they are once again divided into two groups for both race and gender:

The white players have lower averages in each skill. Batting and pitching are quite close, but the two biggest gaps from either chart are in the running and fielding columns, where the players of color win out by 0.42 points and 0.53 points, respectively. A lot of those differences are derived from the imbalance in four- and one-skill point ratings. Six players have four-skill point running, and Pete Wheeler is the only one in the bunch who is white, and three of the four slow-pokes with only one skill point also are white. Fielding is a similar story: None of the game’s best fielders is white, and just one of the three one-point ratings is not. Even on a scale as small as one to four, an imbalance at the extremes will make an impact that cannot be ignored.

The gender splits are once again quite close despite the male players coming out on top in three of the four skills. Male players are slightly better fielders, and the 0.20 point edge in batting belongs to the male players, though an equal one goes to the female players in running. With the fewest total points of all the skills, pitching easily could have swung towards one side with just a couple of extreme ratings, but it is actually the tightest of all. Just 0.07 points separate the two groups, and the two four-skill point ratings and four one-skill point ratings being shared equally between the groups is a big reason why.

Players of color and male players ultimately wield slight advantages over their counterparts, but they are small enough and distributed in such a way that, when crafting teams of nine, balance between the sides is almost inevitable. The end result is that players of the game can choose a character who looks like them or with whom they identify, and the game will not punish them for it on the field. In most games, that is simply not the case.

I have spent a lot of time on the differences between characters that can be counted, but these kids also distinguish themselves with individual characteristics that allow players to identify with them even more. They can mostly be gleaned from their appearance alone, but their brief biographies are also helpful in this regard. Luanne Lui never leaves her teddy bear behind. Kenny Kawaguchi plays from his wheelchair. Annie Frazier’s aversion to running makes catcher her favorite position by far. No one loves the game more than Stephanie Morgan. What makes these personality traits so significant is they allow any kid of any gender and any race to find a common thread with someone, and each of them can hold his or her own on the diamond.

Diving this deep into Backyard Baseball may seem like a silly exercise, and to some extent it is. This is not a game that was created by a large contingent of data scientists who set out to assemble the most statistically balanced sports game of all time. It was made by a small group of developers from Washington state who at one point distributed their product via cereal box, who just wanted to embody the spirit of kid-centric movies like The Sandlot and The Bad News Bears. They just wanted to make a game that showed baseball for what it should be: a game that anyone can be born to play. They succeeded.

While I enjoyed the analysis of this article very much, I can’t help but be disappointed that the inclusion of a player with a disability (Kenny Kawaguchi) is given a treatment equal to characters who “never leave her teddy bear behind” and don’t like to run. The inclusion of a player with a disability is arguably even more forward-thinking than that of the racial composition of the rosters.

Yeah when I saw the headline I kind of thought that’s where this was going. Still a fun article though.

Agreed. The gender/race dimensions are stellar, but other forms of diversity — particularly Kenny’s disability — were standouts at the time. Even minor components like drastic variety in kids’ heights/weights allowed for greater inclusion.

Everything this article says is accurate, but you can step back and find even more.

Super Mega Baseball keeps this legacy going a bit with its cartoony graphics and racially and gender diverse teams. It’s also just a damn fun baseball game.

A little silly *perhaps*, but I enjoyed this article since I never knew anything about the game.

Dour realism has its aficionados, but most people play games for fun!

By the way the 1971 BASBAL was not exactly a video game, it printed the play results. I say this to introduce the anecdote:

“When Daglow ported the game to a batch processing IBM 360 mainframe computer in 1973 this code malfunctioned during testing of the game’s card deck and the game continued for thousands of innings, consuming an entire case of printer paper.”

Kinda sad that there is such an example of inclusion in a game almost no one has heard of, and meanwhile we have the white Sox visiting a known racist as the biggest mainstream media baseball story of the year.

Baseball Stars for the SNES was the first game I remember playing that had a team of women. They were mostly singles slap hitters but it was still a team that could beat you in the early going.

This article brought joy to my heart. An absolute shining fixture in my childhood not just for the gameplay but for the message it sent: everyone can play baseball.

P.S. Achmed was always my favorite too.

Great article, but it would have been nice to see players’ total ratings as well. They may be really balanced in regards to each category, but a player is made up of four categories. If there is a player who has a four in one category but ones and twos in the other, then they are essentially not playable and their four is nonexistent practically speaking.

Great article. I have a similar affinity for “Hardball!” that I played for so many hours on my Apple IIc in the late 80s. Based on the skin tones and names, it was also fairly racially and ethnically diverse for its time, although there weren’t any women.

Did you reach out to any of the programmers or developers to ask about any discussions they had in making the game? That would make a great follow up article. Also, in the spirit of fangraphs, it would be interesting to note if the skills differences between subsets of players were intentional or random.

Dusty Diamond’s All-Star Softball for NES is a gem that many people don’t even know exists. In that game there is a very solid mix of races but there was only 1 female, named Zelda, who could absolutely mash, with a mop. Sure she was a witch and she used a mop for some reason but there was so much more to that game. You could also pick a little devil who was SLOOOOOOOW afoot, but packed a mighty wallop. There was another character, appropriately named Froggy, who hopped as he ran. There were a lot of quirky characters. There was 6 parks to conquer and once you won all of those games, then you would move onto the championship game. In that game, you played a team stocked full of the best players in the game, all of them female. The pitchers had velocity and spin to spare and every one of their hitters had light-tower power. They would likely mash you into a mercy-call a couple of times before you finally bested them. As a kid I remember feeling like a bigger failure losing to a team of girls. But when I picked it back up some 20 years later, I thought, damn, those creators were really ahead of their time.

One of my favorite sports games of all time.

I would like to thank you for your nicely written post

manga kiss