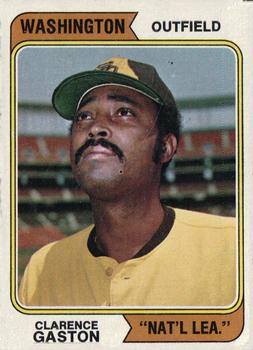

Card Corner Plus: Cito and the ’74 Nationals

Some 40 years ago, when I first saw this card, I gave it a long and curious look. As we inched closer to the start of the 1974 season, I wondered who in the world these “Washington Nationals” were. As far as I knew, Clarence Gaston played for the San Diego Padres. I thought that someone at Topps had lost his mind. As it turned out, Topps had to make a game time decision, and opted to prepare for the real possibility that the Padres would be playing in Washington.

In truth, that scenario almost happened. In 1973, as the Padres played horrendously on their way to 105 losses, they drew fans at a paltry rate. By season’s end, roughly 611,000 fans went to Padres games, the worst figure in the National League. Facing some severe cash flow problems, Padres principal owner Arnholt Smith put the team up for sale during the 1973 season. On May 5, he reached a tentative agreement with Joseph Danzansky, the owner of Giant Food, Inc. Danzansky agreed to pay Smith $12 million, with a down payment of a mere $100,000. A number of news organizations, including the Associated Press, reported the sale as a done deal.

In truth, that scenario almost happened. In 1973, as the Padres played horrendously on their way to 105 losses, they drew fans at a paltry rate. By season’s end, roughly 611,000 fans went to Padres games, the worst figure in the National League. Facing some severe cash flow problems, Padres principal owner Arnholt Smith put the team up for sale during the 1973 season. On May 5, he reached a tentative agreement with Joseph Danzansky, the owner of Giant Food, Inc. Danzansky agreed to pay Smith $12 million, with a down payment of a mere $100,000. A number of news organizations, including the Associated Press, reported the sale as a done deal.

The city of San Diego responded by saying, “Not so fast.” Citing the fact that the Padres still had 10 years remaining on their lease with San Diego Stadium, the city threatened to take legal action against the Padres if they abandoned the city and tried to weasel out of the lease without making major financial restitution.

While most of the National League owners suggested they would support the move, at least two members of the old guard indicated otherwise. According to a September 1973 report in the Washington Post, Cubs owner Philip Wrigley and Dodgers chief Walter O’Malley vehemently opposed the Padres’ move to Washington. Wrigley considered Washington a two-time loser (since both incarnations of the Senators had moved elsewhere) while O’Malley did not want to lose a geographic rival in San Diego.

Some of the other owners also began to question the move to Washington once they heard that attorneys for the city of San Diego planned a lawsuit seeking $72 million in damages. The National League was named in the lawsuit, which meant that the owners would have to pay part of the $72 million if they lost the case. And they wanted no part of that.

In contrast, Commissioner Bowie Kuhn fully supported the proposed move to Washington. If he could convince nine of the National League owners to support the move, that would be enough to ratify the franchise sale and transfer. Kuhn’s support of the Washington move angered Padres GM Buzzie Bavasi, who claimed that the commissioner was attempting to bribe National League owners into approving the move to Washington. Kuhn allegedly told the owners that approving the move would curry favor with Congress, which might look more favorably on continuing baseball’s anti-trust exemption.

By early December, the sale to Danzansky seemed inevitable. The National League released its 1974 schedule, which showed the city of Washington hosting an Opening Day game on April 4 against the Phillies. Wintertime acquisitions of several high-priced veterans, principally Matty Alou, Glenn Beckert, Willie McCovey, and Bobby Tolan, indicated that a sale to the wealthy Washington owner was nearly a foregone conclusion. But at least one of the new Padres indicated reluctance at relocation. “I don’t know if I’ll go [to Washington],” said McCovey, leading to speculation that he might retire.

With Topps readying for full-scale production of its 1974 set, the company faced a decision with regard to its new cards. Topps came up with a compromise. The company printed some of the Padres player cards with “San Diego” and “Padres” printed on the banners featured at the top and bottom of the cards. But they also printed some of the Padres cards with “Washington” and “Nat’l League” on the banners. One of those cards was the Gaston card.

So what happened to the seemingly inevitable move to Washington? As it turned out, the threat of legal action against the Padres and the National League proved to be too much to overcome, giving everyone cold feet in the process. San Diego’s mayor, Pete Wilson, threatened to “wage war” against the National League. Danzansky and his backers could not reach a deal with Smith. And then in January, a local answer resolved the situation. Ray Kroc, the founder of the very successful McDonald’s franchise, agreed to buy the team and keep it in San Diego for the immediate future. Kroc matched Danzansky’s offer and signed a revised lease that promised to keep the team in San Diego through at least the 1980 season.

So Gaston, McCovey, and the rest of the Padres geared up for a season in San Diego. Aside from the obvious designations of Washington and National League, the other feature that stands out on the Gaston card is the player’s name. He was not yet called “Cito” Gaston, the name that he became known by as a manager with the Blue Jays; he was still known solely as “Clarence” Gaston in 1974. Cito has stuck so well as a nickname that we almost forget that he was known by his given name of Clarence throughout much of his playing days. In fact, all of the cards that Topps issued of Gaston as a player, up through the 1979 set, refer to him as Clarence.

Long before he became a manager, Gaston was also a highly touted outfielder. Originally signed by the Milwaukee Braves in 1964 (just one year before the installation of the amateur draft), Gaston had the ideal build for a ballplayer. Long and lean, he stood six foot, three inches tall and weighed 190 pounds, just the kind of body type that scouts forever seek in young players, particularly outfielders. After signing, Gaston reported to Greeneville of the Western Carolinas league and struggled to a .230 average in 49 games. He fared no better in the New York-Penn League, where a .238 batting average for Binghamton did little to improve his confidence.

The first-year problems only multiplied, carrying over into his second season. An assignment to the Florida State League resulted in a paltry .188 batting average and no home runs in 202 at-bats. With two lost seasons at the lower levels of the farm system, the Braves must have fretted that Gaston would never hit.

Figuring that they had nothing to lose, the Braves (by now relocated to Atlanta) farmed him out to Batavia, an unaffiliated team in the NY-Penn League. The change of scenery worked wonders, as Gaston exploded, hitting .330 with 28 home runs and a .589 slugging percentage. He played so well that the Braves pushed him up to the Double-A Texas League near the summer’s end and watched him pick up three hits in 10 additional at-bats, completing a remarkable transformation for a player who had looked like a candidate for release just one year earlier.

In 1967, Gaston continued to hit well in the Texas League, where he put up a .305 batting average and reached base 36 percent of the time. Gaston’s strikeouts (104 for the year) did cause concern, but not enough to discourage the Braves from recalling him late in the summer. Given a September cameo, he came to bat 25 times, but collected only three hits.

Though Gaston’s cup of coffee with the Braves lasted a handful of games, it paid a huge dividend for the young outfielder. The Braves roomed him with a veteran, a 30-year-old Hank Aaron. Gaston and Aaron struck up a quick and lasting friendship. To this day, Gaston credits Aaron for the guidance that he supplied in helping him mature.

The experienced helped Gaston, but he clearly wasn’t ready to hit in the major leagues. Based on his lack of plate discipline, the Braves wisely sent Gaston back to the Texas League in 1968. He ended up splitting the season between Double-A and Triple-A ball, but did not put up big numbers. The Braves decided not to protect him from the upcoming expansion draft, figuring the Expos and the Padres might be scared off by his high strikeout totals. But the Padres, with their final pick of the expansion draft, called Gaston’s name.

That winter, Gaston tore up the Venezuelan Winter League, where he led all batters with a .383 average. The Padres took notice. Gaston made the Padres’ Opening Day roster, but started the season on the bench. That situation changed during the season’s first week, when manager Preston Gomez made the 25-year-old Gaston his starting center fielder. Gomez became enthralled with Gaston’s defensive play, including his strong arm. In contrast, Gomez and the rest of the Padres suffered through Gaston’s many offensive slumps. He hit .230 with two home runs, walked only 24 times, and struck out 117 times. A shin infection and an injury to his foot did not help matters. All in all, it was a ghastly season for Gaston at the plate.

A patient Gomez stayed with Gaston as his center fielder in 1970. This time Gaston made the necessary adjustments, listening to several sources of good advice. Cubs star Billy Williams suggested he use a lighter bat. Padres batting coach Bob Skinner refined his swing. Bolstered by the recommendations, a more relaxed Gaston put forth a career year. Though he still struck out too often and didn’t walk enough, he hit a scintillating .318 and launched 28 home runs, making himself one of the National League’s best all-around center fielders. Fittingly, he won selection to the All-Star team, for the first and only time in his career.

Gaston played so well that the Braves publicly expressed regrets that they had let him go. “Clarence is the one player with the Padres who could make our lineup,” said Braves manager Lum Harris. “We know that now, but we didn’t know it when he let him go in the expansion draft.”

The Padres hoped that Gaston had turned the corner completely, but he would never again match his 1970 numbers. The following year, he still hit 17 home runs, but otherwise struggled. At one point, he realized that he was using a bat that was the wrong weight for him. His batting average dropped, nearly 100 points by season’s end, as he became even more aggressive, drawing a scant 24 walks. That simply would not do.

Over the next three seasons, Gaston continued to struggle, even as he moved from center field to right field to make room for the speedy Johnny Jeter. The formula was familiar: about four strikeouts for every one walk, along with diminishing batting averages. During the spring of 1973, Gaston drew the wrath of Padres president Buzzie Bavasi, who was furious that Gaston reported to camp at 232 pounds. “He’s 20 pounds heavier than he was three years ago, when he hit .318,” Bavasi complained to The Sporting News. “He’s spent three weeks trying to get in shape. He should have been in shape when he got here.”

Gaston hit 16 home runs that season, but his .250 average and 20 walks did not please Bavasi. In 1974, the rise of a young Dave Winfield, along with the acquisition of Bobby Tolan, cut severely into Gaston’s playing time. Gaston also turned 30 during the ‘74 season. Convinced that he would never again capture his 1970 form, the Padres decided to cut their losses that winter. They sent Gaston back to his original team, the Braves, in a straight-up deal for reliever Danny Frisella.

Wisely, the Braves did not play Gaston every day, instead using him as a fourth and fifth outfielder behind starters Ralph Garr, Rowland Office, and Dusty Baker. Gaston did respectably, compiling a .718 OPS in 141 at-bats.

Gaston found a comfort zone in Atlanta, where he gave the Braves good defensive play and emerged as their top right-handed pinch-hitter. He remained with the Braves deep into the 1978 season, when the Pirates came calling in a frantic bid to win the National League East. On September 22, the pennant-contending Bucs purchased the 34-year-old flychaser in a straight cash deal. Gaston picked up a hit in two at-bats as the Pirates fell just short of the divisional crown, losing to the Phillies by a game and a half.

With a surplus of outfielders, the Pirates decided to let Gaston go after the season ended. Not wanting to give up the dream, Gaston signed on with the renegade Inter-American League, where he enjoyed a reunion of sorts with former teammates Jeter, Dave May, and Tito Fuentes. Gaston batted .328 for Santo Domingo, but the league folded up in midsummer, leaving him temporarily unemployed. He then hooked up with a team in the Mexican League, where he finished out the season.

After the 1978 season, Gaston dropped some excess weight and received an invitation to spring training at the behest of Indians catcher Cliff Johnson. The Indians gave him a non-roster invite, but did not include him on the Opening Day roster. So he returned to the Mexican League, where he played one additional season before finally calling it quits.

Although his playing career was mediocre at best, Gaston would find greater rewards in coaching and managing. In 1982, the Blue Jays hired him as their batting coach. By this time, Gaston officially took on his second identity. While he was growing up in Texas, a friend of his noticed a resemblance between Gaston and a Mexican wrestler known as “Cito” and began calling him by that name. Strangely, the nickname did not begin to stick until the 1980s. Gaston liked the moniker, and despite the ensuing confusion, the name took on a life of its own. Hence, Cito Gaston was born.

Remaining in his post as batting coach for almost the balance of the 1980s, Gaston became extraordinarily popular with his players, who loved his open style of communication. After a bad start to the 1989 season, the Jays fired their manager, Jimy Williams, and sought a replacement. Several Blue Jays, including George Bell and Rance Mulliniks, encouraged GM Pat Gillick to offer the job to Gaston, which he did.

At first Gaston turned down the offer, mostly because he enjoyed his role as hitting instructor, but a number of players urged him to take the job. Gaston relented, becoming only the fourth African-American manager in major league history, after Frank Robinson, Larry Doby, and Maury Wills. No one could have realized it at the time, but Gaston, the least known of the four pioneers, would emerge as the most successful.

Known as a players’ manager who excelled at communicating, Gaston led the Jays to five divisional titles, culminating in World Series championships in 1992 and ’93. Including a later stint as manager, he has compiled a lifetime winning percentage of .516. He is one of a handful of managers to have won two World Series without making the Hall of Fame.

Now a consultant with the Jays, Gaston’s managerial days are probably behind him. But he has retained his reputation as one of the sport’s nice guys, someone that you like as soon as you meet him. He is the kind of man that you root for, hoping that he will have one more chance to manage, one more chance to win a third World Series and solidify his case for the Hall of Fame.

Just don’t call him Clarence. It’s Cito. And don’t tell him he ever played for the 1974 “Washington Nationals,” because they never existed.

Cliff Johnson and Cito went to Wheatley High School (since closed) in San Antonio graduating two years apart.

Actually, Wheatley High School merely changed back to its original name-Brackenridge High School.

I’m glad to see that you’re still writing for Hardball Times, Bruce. Fine article.

I remember attending a Padres-Phillies game in Philadelphia in 1974 that featured a rowdy group of baseball fans from Washington rooting for their “home” team. At that point, D.C. had been without baseball for only a few years — if they only knew how long they’d have to wait! I also remember one guy holding up a sign that said, “Welcome, Washington Cadres.”

I went to a lot of Dodger games in ’74 and remember going early one night and sitting in the left field pavilion for batting practice. This big guy for the Padres was cranking them out to left and we had to buy a program to find out who this guy was. Well, looking at his total of 2 homers for the year, we were stunned Clarence Gaston was hitting hitting ’em out like that. Nate Colbert was matching Gaston for BP homers that night. He ended up with nine and Cito six for the year.

My understanding of the matter is that Cito just doesn’t want to manage anymore. He only came back in ’08 because the clubhouse was a toxic waste dump, which he fixed (always something he did as a manager as well as anyone who’s ever managed), and then guided the ship for a couple more years before going back to the front office. As far as I know, the Blue Jays would have let him go on if he wanted to.

I always thought he would have been a perfect manager for the Yankees if the timing had ever been right. He handles clubhouse personalities and keeps the atmosphere healthy, is able to maintain the respect of his players, is much better with veteran players, and when he has a team that can win, he lets them go out there and win.

Cito, is that you?

This comment, as well as the end of the article itself, have my head on the verge of exploding.

Gaston never earned many accolades back in the ’90s, and rightly so. He was a stubborn man who did a terrible job of managing his lineup and his bullpen, his “do nothing” methods largely based on some very strange perceptions he had formed during his flash-in-the-pan MLB career. The Blue Jays were back-to-back World Series champions because of an enormous payroll filled with excellent players, not because of anything remotely resembling managerial genius – and in fact the only reason he managed those teams at all is because Blue Jays upper management overruled the GM’s decision to fire Gaston after the 1991 season.

His 1993 All-Star Game shenanigans showed his true colours to the rest of the league – his roster decisions were questionable enough, but then he showed up Mike Mussina by refusing to bring in the hometown pitcher to close out the game, infuriating fans and players alike. After the game, he doubled down on his dick move, calling Mussina classless and saying he wouldn’t get to play the next year, either.

By 1997 Toronto’s own relationship with Gaston had turned sour, and Gaston turned sour back, most famously when he accused three of the more critical members of Toronto’s media of racism. 17 years later, he still refuses to apologize.

And for a so-called “player’s manager” he sure was disliked by an awful lot of his players over the years. Roger Clemens, David Wells, and Shawn Green were just a few of the superstars Cito clashed with in the old days; Vernon Wells, Aaron Hill, Travis Snider, oh god there were so many in just those few short years of his return.

Cito Gaston was an awful manager. Take off the rose-coloured glasses and you’ll see it, too.

Aaron, if you want to argue that Gaston was overrated or mediocre or subpar as a manager, I could see that. But you reach such extremes in your critique of Gaston that it’s hard to give the criticism much credibility. We’ve seen many talented teams underachieve over the years–the Mets of the early 1990s and the Orioles of the mid-to-late 1990s immediately come to mind–and fall short of World Series expectations. If Gaston were as bad as you say–and you’re making him out to be one of the worst managers of all-time– the Jays would never have come close to winning the World Series those two years. Bad managers can hurt good teams significantly, but Gaston never seemed to do that. After all, his won-loss record is well above .500.

You mention some of the players he had trouble with, like Clemens and Wells. Both of those players were difficult to manage throughout their careers; they had trouble with multiple managers, not just Gaston. And I’m not sure why you would include Travis Snider, a perennial underachiever who has done nothing since leaving the Jays. Vernon Wells or Shawn Green I can understand, but Snider’s inclusion does nothing to further the contention that Gaston was some sort of incompetent buffoon.

That’s a really, really bad argument. A manager’s record is about as useful as a pitcher’s record.

A manager who uses Devon White as a .300 OBP leadoff man, who lets Shawn Green and Carlos Delgado ride the pine, who thinks John Olerud is in Joe Carter’s way, who works pitchers into the ground and leaves them out there to die even if they’re on post-injury pitch counts, that’s not a manager who’s contributing in any positive way to his team’s record.

His in-game strategy was non-existent, a very significant number of his players absolutely hated playing for him, and he was just about fired at the end of the 1991 season for all the same qualities that, somehow, he’s now regaled for.

He chose bad players over good ones, and turned plenty of good players into bad ones. He. Was. Awful.

Cool article. But some errors. Hank Aaron was 33 in 1967, not 30. Also, you say that Cleveland invited him to spring training for the 1979 season. That must have been 1980 if he spent ’78 with Atlanta and Pittsburgh, and ’79 with the Inter-American League’s team in Santo Domingo.

From a historical perspective, this quote shouts out: “Kuhn allegedly told the owners that approving the move would curry favor with Congress, which might look more favorably on continuing baseball’s anti-trust exemption.” First, the anti trust exemption was never in jeopardy. It was a judicial creation premised on the idiotic assumption that baseball was not a business. Second, Kuhn’s thinking reflects the owners’ real fear of the Flood lawsuit and its aftermath. The owners won but their tactics were being exposed as almost dishonest. Third, the quote is funny in a way. Sort of like Kuhn saying, “hey look guys, we may have a big problem brewing on Capitol Hill. Why not bribe these hayseeds with a baseball team and give them all kinds of freebies and off the books gratuities so they leave us alone.” Kind of like Outback, facing a congressional investigation over unsafe meat, decides to build a beautiful restaurant next to the Hill.

On its most basic level, a manager’s job is to get his players to perform well for him. Cito Gaston has an excellent track record in that department. Players like Olerud, Alomar, Fernandez, Carter, Key, Ward, and Henke all had some of their best seasons while playing for Gaston. That doesn’t mean they all liked, but they played well for him, and that’s the bottom line.

We can criticize even the greatest managers for bizarre individual decisions–batting the wrong man in the leadoff spot, leaving his starters in too long, not knowing when to pinch-hit for the right batter–but we need to looking at the big picture in assessing any manager. Far more important than individual strategic decisions are the manager’s ability to build a unified team filled with players who play hard. Gaston’s championship teams certainly had those qualities. Does he have a harmonious clubhouse? Yes, Gaston did. Do the vast majority of players like playing for him? Based on the comments I’ve read about Gaston, the answer would again be yes.

I can find individual weaknesses in any manager from Connie Mack to John McGraw to Sparky Anderson, but the larger context is what matters. And final results, like wins and losses, do matter. This is, after all, a results business.

I raise a practical question… Had the Padres moved to Washington in 1974, they’d have moved to the NL East, so which East team would have switched to the West? The Cubs and Cardinals have always been fierce rivals, so I can’t imagine only one of them leaving.

Thanks for this piece – I have this card and never realized Clarance and Cito where one-in-the-same.

Re AndrewJ. Atlanta would have gone to the East along with Washington. Chicago and St. Louis would have gone to the West. Chicago was in the AL West so it would have not seemed odd. St. Louis is further west than Cincinnati so, again, no PR problem. I never understood why Cincinnati was in the West while the Cards were in the East.

Thanks for the clarification, Dennis. Of course, it was championing putting teams in their proper divisions which sealed Fay Vincent’s fate in the early 1990s…

Dennis, what I understood is that the Cubs and Cards were against going to the West when divisional alignment took place in 68/69, they wanted to stay in the East with New York (like the Tigers in ’93). They would only go along with divisional alignment if they were in the Eastern Division.

If that’s true about Devon White having a .300 OBP (this guy’s ranting doesn’t warrant the time to look it up), that makes Cito’s managing look even better as he was able to get such production out of his lineup DESPITE such a crappy leadoff hitter. I bet a good 15-20 teams would have loved to have him as manager in the early ’90s.

Here is a link to more interesting info about the decision by Topps to print up these babies:

http://www.sportscollectorsdaily.com/1974-topps-washington-nationals-the-year-topps-jumped-the-gun/

about realignment of the divisions had sd moved to washington: the cubs were not leaving the east.

period.

the wrigley family was simply not going to let wgn lose its 10 o’clock news for pt night games, starting at 9;30, or 10, chicago time.

it really was that simple, and wrigley, that significant.

the saint louis-chicago pairing is too often over played.

it was important when team income was attendance driven, but after 1960, not really notable.

stl would have been a good fit in the nl west.