Did John McGraw Have a Bullpen Edge?

John McGraw was ahead of his time when it came to bullpen usage. (via Mears Auction)

Bill James has written more about baseball—encompassing history, analytics, and opinion—than I will ever get to read. That doesn’t stop me from reading, and often re-reading, his work. One old passage of his I came across recently covered all three elements I just named, and offered a prediction that he didn’t test—but I can.

In The Bill James Guide to Baseball Managers, James examined the managerial style of John McGraw, iconic field marshal of the New York Giants in the first third of the 20th century. One main characteristic James observed was that McGraw was more prone to use relief pitchers than the rest of the league, for his entire career. His teams led the National League in saves (figured retroactively) more than half the seasons he managed, decades before the save emerged as a concept.

Due to McGraw’s cutting-edge tactics in this regard, James speculated about what it meant for the Giants’ on-field success:

This was probably worth at least five games a year to his teams. I don’t have statistics to prove this—it hasn’t been studied—but I would bet that a typical team in the early 1920s probably blew 20 to 25 leads in the late innings. McGraw’s teams probably blew 15 to 20.

I love tracking down this kind of esoteric information. I love having good excuses for tracking it, such as fact-checking the biggest name in baseball analytics. I especially love Retrosheet making it possible to track this information just* by downloading a few files.

* It wasn’t quite as simple as that, but it beats the daylights out of poring through hundreds of newspapers for thousands of box scores.

So I did track down whether McGraw’s relief machinations saved his Giants five games a year. Before I start dropping numbers, though, it’s worthwhile to look at some of the facts behind the figures.

A Brief Pre-History of the Bullpen

There has almost always been relief pitching in major-league baseball. Occasionally a starting pitcher would get hurt or be too tired or too ineffective, and another player would be put in the box. As the game developed, and demands on starting pitchers rose (notably in 1893 when the pitcher got moved back to 60 feet six inches), relief pitching grew beyond an emergency measure into something not uncommon, if still not routine either.

At the start of the 20th century, a general method began emerging on assigning relief roles. If a good pitcher hadn’t thrown in the last day or two, and that day’s starter faltered in a tight game, the good pitcher would relieve him. (If said pitcher hadn’t thrown in the last three days, he probably wouldn’t be available to relieve because he’d be the starter.) The lists of league leaders in wins and in saves had a lot of overlap (once historians went back and figured saves for those years).

McGraw was a leader in this method, lacking the reticence to pull his starters that many other managers had. He probably learned this from Ned Hanlon, his manager when he played on the 1890’s Baltimore Orioles. Hanlon teams had the two highest save totals of the 19th century.

McGraw learned well from this highly influential manager. His Giants began regularly leading the National League in saves, and individual Giants pitchers did likewise. This served him well … until 1908.

In that epic pennant race, McGraw’s pitching staff went from a strength to a millstone. He couldn’t get consistency from anybody but Christy Mathewson. Increasingly, Matty got the call not only in the rotation but whenever a fire broke out late. Mathewson led the NL that year in total games, games started, complete games, shutouts, and wins, all while tying for the lead in saves.

But it came at a dire cost. In the final 37 days of the season, Mathewson pitched 110.1 innings, starting and relieving. That is the equivalent of throwing a complete game every three days—for five weeks.

It is no surprise that he reached the end of the line exhausted. Despite four days’ rest before the pennant-deciding game against the Chicago Cubs, Mathewson’s arm had next to nothing. He lost the game 4-2, and the pennant with it.

This experience appeared to change McGraw’s thinking. He had to limit his ace’s workload, ideally by minimizing his relief duties. The relief burden had to shift somewhere, though, and McGraw had an idea for that.

In 1908, he gave a 29-year-old rookie named Bill Malarkey 15 relief stints without a single start. This was part stopgap, part McGraw’s way of testing Malarkey’s viability as a pitcher. (Malarkey flunked: he never pitched in the bigs again.) For 1909, he selected another un-seasoned pitcher on his roster for a similar role: Otis “Doc” Crandall.

Doc would start eight games in 1909, and relieve in 22. This was a record, which Crandall would break the next year. And the next, and the next, and the next. He still had some starting duties, but his main job was relief pitching.

He was, however, about as far from a closer as a reliever can be. As shown by James and later by Chris Jaffe in their respective tomes on managers, Doc was essentially a garbage-time reliever. He seldom came in with a small lead, like today’s relief aces, but often when the Giants were behind. He had rather few saves, and substantially more relief wins, coming when New York’s strong offense got back what the starters had given up.

McGraw had discovered the concept of pitcher leverage, but was working it from the other side. He used the middling Crandall in low-leverage relief stints, taking that piece of the overall workload off his best hurlers. Christy Mathewson, for instance, dropped from a dozen relief appearances in 1908 to just four in ’09.

The Crandall experiment ended when Doc jumped to the Federal League for 1914. At the same time, Christy Mathewson’s superb career began flaming out. The Giants got overhauled by the Miracle Braves late in 1914, then crashed to last place in ’15. McGraw had to rebuild, and rethink.

His new method was to spread out the starting duties more broadly, no longer leaning hard on any aces. This allowed McGraw to give those starters more relief assignments without risking overwork. He still used some untested arms primarily or exclusively as relievers, but they didn’t come out of the bullpen as often as Crandall had, largely because they didn’t have to.

The formula worked, or at least didn’t stop them. McGraw’s Giants won the pennant in 1917, then reeled off four straight flags from 1921-24. And for the entire 1917-24 stretch, all eight years, his team led the NL in the not-yet-tabulated category of saves.

This was the cutting edge of relief pitching for a while. The Washington Senators used Firpo Marberry as a relief ace during their two pennant years in the mid-1920s, but due to his success there they slid him back into a starting role. The mindset remained that if you were a good pitcher, you needed to be a starter. It would take until the latter 1930s for anything resembling the bullpen as we now know it to begin taking shape in the majors. John McGraw remained ahead of the curve, if only because the curve was moving so slowly.

Holding On

I took as my main time period the years 1921 to 1923, corresponding to James’s talk of “a typical team in the early 1920’s.” I also checked the year 1913, way back in Doc Crandall’s era as a Giants reliever, out of curiosity about how this relief set-up affected the team’s performance.

One hitch was determining what Bill James meant by “in the late innings.” I concluded that his cut-off had to be at least six innings, and certainly no more than seven. (A cut-off at eight usually leaves you a final inning, not innings.) I looked at both, so I could choose whichever definition came closer to his surmises about lead-blowing frequency.

So I checked, in each game, whether each team lost a lead after six or after seven innings. Note that they did not have to hold this lead at the cut-off point. A team that was tied through six and seven, moved ahead in the eighth, and lost the lead in the ninth would count as blowing a lead. A team that made a comeback in the ninth, then took and subsequently lost a lead in extra innings would count as blowing a lead. We’re examining late-inning pitching patterns in an age when starters could well go deep into extras, so I thought that proper.

Also note that a blown lead does not necessarily mean a loss. Comebacks happen. Both teams can blow late leads, and only one will suffer the loss (or even zero: this pre-night ball era still had a fair amount of tied games.). I counted blown lead defeats separately, but for the moment I’m dealing with just the blown leads.

Also also note: a team can blow late leads more than once in a game, but I only count it as one. I’m sure that is what James meant, and what most people would mean.

In the ’21-’23 range, there were a total of 992 blown leads after six innings in the majors, and 645 blown leads after seven innings. This works out to 20.67 blown leads per team per year after six innings, and 13.44 blown leads after seven. The six-inning number fits James’s 20-25 range, so I will gladly assume that’s what he meant all along and work with that from here on.

So did McGraw, with his bullpen tactics, blow fewer leads than the rest of the league?

| Year | BRO | BSN | CHN | CIN | NYG | PHI | PIT | SLN | NL Av. |

| 1921 | 19 | 27 | 26 | 20 | 20 | 16 | 20 | 20 | 21.00 |

| 1922 | 24 | 22 | 17 | 17 | 20 | 23 | 19 | 23 | 20.63 |

| 1923 | 15 | 20 | 26 | 24 | 17 | 22 | 18 | 30 | 21.50 |

| Total | 58 | 69 | 69 | 61 | 57 | 61 | 57 | 73 | 63.13 |

Not by as much as James thought. The Giants blew an average of 19 late leads a season, when the National League averaged 21.04. The American League had similar numbers, its teams blowing an average of 20.29 late leads per year. McGraw’s boys did outperform the league, but not by five games a season.

Blown leads don’t work out so well, but what about blown games, late leads turned to defeats?

| Year | BRO | BSN | CHN | CIN | NYG | PHI | PIT | SLN | NL Av. |

| 1921 | 18 | 19 | 14 | 13 | 14 | 11 | 9 | 16 | 14.25 |

| 1922 | 16 | 18 | 11 | 10 | 11 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 14.13 |

| 1923 | 11 | 18 | 15 | 8 | 9 | 15 | 13 | 17 | 13.25 |

| Total | 45 | 55 | 40 | 31 | 34 | 41 | 37 | 48 | 41.63 |

The Giants’ record is actually a little better here. They blew 34 games in a three-year span when the average NL team was blowing 41.63, for a difference of just over two and a half games a year. If we also take a peek at 1913, we see the Giants widening the gap between blown leads and blown games.

| Type | BRO | BSN | CHN | CIN | NYG | PHI | PIT | SLN | NL Av. |

| Leads | 18 | 17 | 16 | 21 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 13 | 18.13 |

| Games | 12 | 11 | 8 | 15 | 9 | 12 | 17 | 11 | 11.88 |

The Doc Crandall Giants weren’t blowing fewer late leads than average, but they were preventing blown games more efficiently. One possible explanation is that the Giants’ late-game pitchers were limiting the damage when losing a lead, leaving the offense a tie or one-run deficit that they could make up with greater ease.

Another possibility arises from a confounding factor that these four Giants teams share: they all won the pennant. They were very good teams, meaning their hitting was probably quite strong. That implies those Giants were building big leads that couldn’t be overcome, or had strong prospects to rally after an opponent’s comeback and retake the lead.

We can presume these teams hit better than the average—or we can look at the numbers. In 1913 and 1921-23, Giants’ hitters batted six, nine, eight, and 10 points, respectively, above league-average and park-adjusted OPS+.

Going by points above average rather than simple OPS+ was necessary because Baseball-Reference excludes pitchers from league calculations but not team calculations, so the teams end up collectively well below 100. Odd, but easily worked around, and we see that the Giants were strong offensive teams in all of those years. They led the NL in ’23, and were second the other three seasons.

So did this effect operate in general, beyond the Giants’ specific case? Did being a good offensive team, or a bad one, affect how often you lost from blowing a late lead?

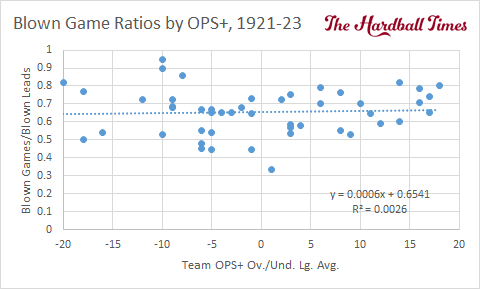

I saw two ways to approach the question. I could compare OPS+ to raw figures of blown games, or compare it to the proportion of blown late leads that led to losses. The latter would acknowledge late pitching’s role in losing that lead, while measuring the ability of the offense to redeem their failure. As I like to do when I’m not sure about the proper attack, I did it both ways.

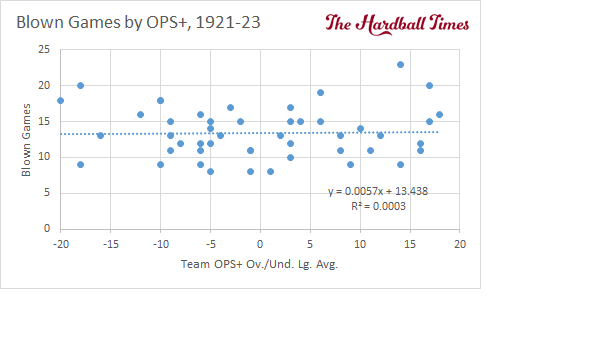

Turns out, it was an illusion both ways. I used both National and American League teams to fill out the sample size for those years, and still got next to zero correlation. The trendlines were nearly flat, and what little slope they had showed more blown games by the better offenses.

So with the influence of offensive ability washing out of the equation, we are left with what the numbers showed us. McGraw’s Giants in the early 1920s were better than the league at preserving late leads, by about two games a year for leads preserved and by two and a half per year for comeback losses prevented. The effect was only about half as strong as Bill James predicted, but it did exist. McGraw was wringing out some extra wins with his late-game pitching moves.

McGraw Versus the Modern Bullpen

The 1920’s were a long time ago in baseball terms, and by development of relief pitching doctrine, they are almost prehistoric. With today’s seven or eight-man bullpens, platoon specialists, and assignments by inning, one would expect teams to be better at holding late leads today than they were almost a century ago.

So while it’s not exactly part of my original subject matter, I decided to compare blown-lead figures of the 21st century to those of McGraw’s era. For the best match, I looked for a recent year with a runs per game total as close as reasonably possible to the early 1920s. (More or fewer runs per game would presumably make it harder or easier to hold late leads.) I found 2007 had 4.80 R/G, compared with 4.81 for the 1921-23 NL and 4.84 for the ’21-’23 majors. Anything more recent was significantly lower, so 2007 it was.

I tallied the ratio of blown leads and blown games to total games played for 2007, for 1921-23, and also for 1913 to get a peek at what the numbers were like in the Deadball Era.

| Type | 2007 | 1921-23 | 1913 |

| BLd/Gm | 0.116 | 0.134 | 0.109 |

| BGm/Gm | 0.079 | 0.087 | 0.072 |

Modern bullpen doctrine makes a difference. The rates of blown games in 2007 are further from those of the similar run environment of the early 1920s than they are from the deadball year of 1913. There might be a confounding effect in the ways those runs are scored—big innings versus run-at-a-time tactics—but I lean toward calling this a genuine effect, on the order of a game and a third saved per season.

But this is league versus league. What if we slipped in McGraw’s teams of the early ‘20s for comparison?

| Type | 2007 ML | 1921-23 ML | 1921-23 McGraw |

| BLd/Gm | 0.116 | 0.134 | 0.122 |

| BGm/Gm | 0.079 | 0.087 | 0.074 |

McGraw’s Giants played more like they had a 21st-century bullpen than a Roaring ‘20s pitching roster. They actually beat the 2007 average on late blown games.

Some caution is in order. The 462 games the Giants played over those three years is a limited sample size, and perhaps the effect of a strong offense is there despite not showing up in the OPS+ charts. Still, there is a basis for saying that, by the effects gained, John McGraw’s relief tactics put his Giants a few generations ahead of the National League of his day.

Am I saying teams today should go back to employing starters in relief roles the way the Little Napoleon did in the 1920s? That’s a really big step. So much has changed in the game, like more regularized schedules permitting strict starter rotations, and the training and expectations of pitchers themselves. Odds are, you can’t get there from here. Besides which, you’d risk losing something from the starters for the dubious benefit of doing about as well in the late innings.

And it’s important to remember why McGraw was doing this. He was trying to ease the burden on his best starters. The bullpen was the means, not the end: he would have considered prioritizing relief pitchers to be backwards. Anyone doing it McGraw’s way today would not be doing it for McGraw’s reasons, another strike against the idea.

But who knows? Bullpens have gotten as large as they practically can, despite the continuing pressure to add more and more arms. Bringing in starters at the right time to shoulder some of the late-inning burden could be the next development, if some manager is daring enough to make that move.

If he does, though, don’t laud him too much for trying something new. He’ll actually be trying something very old.

References and Resources

- The Bill James Guide to Baseball Managers

- Chris Jaffe, Evaluating Baseball’s Managers

- Cait Murphy, Crazy ‘08

- Retrosheet

- Baseball-Reference

Interesting article.

Bravo !!! J'ai hâte d'en savoir plus sur le projet concret… Une bière un de ces 4 ? Bonne année 2012, pleine de prises de risques, de rencontres enrichissantes, de nouvelles compétences acquises sur le terrain, de moments de travail intense et de rires encore plus in&sseent#8230;et de beaucoup de succès bien sûr !

I keep wondering when someone will go back to a 4 man rotation- with starters “limited” to 100 pitches today, there is really no reason that a 4 man rotation could not be used, with the 5th starter being the long man and spot starter…With off days and the occasional use of the 5th starter it could be done, but I am not sure that modern pitchers nor their agents would agree. “It is easier to find 4 good starters than 5.” Earl Weaver

The Colorado Rockies tried something like that a few years back. Four starters, limited to around 75 pitches. They gave it up in a month or so: it wasn’t helping on the field, and I strongly suspect their starters weren’t buying in much.

Big experiments are big risks, leading to big chances that someone will get fired if they don’t pan out. It’s easier to stay with the herd.

Well, something needs to be done to reverse the 12, 13, even 14 man pitching staffs now; it’s a whole different game and I think inferior. If large staffs are here to stay, maybe think about having a flexible 28-man active roster, with 25 being activated on a given day. You could inactivate tomorrow’s starter, yesterday’s starter, plus another player (rotate mop up guys back and forth, or keep a third catcher, etc). That would allow a couple of more bench players and make the game more reasonable.

Regardless of how one feels about all the identity concealing, the Yeezy Mafia team certainly are consistent about it. Their website is even registered through Privacy Protection, a company that hides the contact info of site owners from the public WHOIS database.