Exploring Extreme Ballparks Past

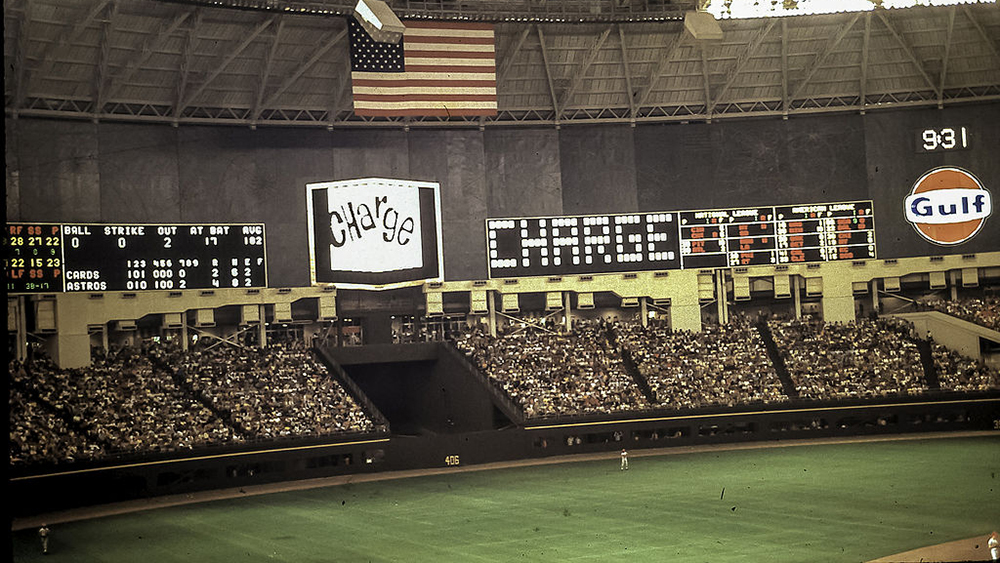

The Astrodome was one of the more pitcher friendly ballparks in MLB history. (via Bill Wilson)

Editor’s Note: Portions of this article were adapted from the new book, “Ballparks: A Journey Through the Fields of the Past, Present, and Future,” available now from Chartwell Books.

Ewing Field, San Francisco’s notoriously short-lived ballpark, was one of the finest stadiums in America when it opened in May 1914. With a capacity of 17,500 and a price tag of a quarter million dollars, the Double-A park was larger and more expensive than several of its major league counterparts. The new ballpark had the Bay Area brimming with excitement — an excitement which, unfortunately, was short lived once actual games started being played. It became quickly apparent that Ewing Field was utterly useless as a ballpark, and its first season of baseball turned out to be its last.

How did one of the world’s finest baseball venues become a white elephant overnight? Blame it on the weather. Ewing Field had been built near the summit of San Francisco’s most desolate hill, Lone Mountain, where frigid, wintry winds whipped through the neighborhood most of the year. The San Francisco Seals had gotten a sweetheart lease from the local archdiocese on a plot of land fit only for the dead. (That was literally true — the rest of Lone Mountain housed the city’s various cemeteries, containing some 100,000 bodies, and the view from the stands was tombstones virtually as far as the eye could see.)

Not for the last time, San Francisco baseball officials had failed to accurately assess the weather conditions at the site where they built a new ballpark. But Ewing Field, if anything, was an even bigger disaster than Candlestick half a century later. “The cold wind whistled around Lone Mountain and shot down on the green of the ball field to make you shiver,” the San Francisco Chronicle wrote on Opening Day, “and it is quite within reason that it interfered with the quality of the pitching.” One disgruntled fan complained that “you ought to call it Icicle Field.”

As the El Niño summer of 1914 progressed, conditions got even worse, and fans began staying away from Ewing Field in droves. Attendance slipped to 200 at one game, of which the Chronicle wrote: “The field was so slippery there was hardly a chance for the men to steady themselves; the ball so wet that pitching of any quality was impossible; and the track was so heavy that base running was out of the question.” There’s a story — which, sadly, is probably apocryphal — about a freezing fielder building a campfire on the outfield grass to keep warm.

Before Ewing Field’s first season was even over, Seals ownership gave up. They announced plans to abandon it and return to the team’s ramshackle old ballpark, and Ewing never hosted professional baseball again. Half-forgotten, it burned down in 1926.

Ewing Field is perhaps the most vivid example of an extreme ballpark affecting game play — anyone know how sitting by a campfire affects an outfielder’s range factor? — but it’s hardly unique in baseball history. Every era has had stadiums whose dimensions, weather, or other characteristics created an extreme environment for baseball. Here’s a look at several more such parks from baseball’s past.

Astrodome (Astros, 1965-99)

Though the Astrodome’s dimensions were relatively normal, it was obvious from the beginning that the world’s first indoor stadium would be friendly to the men on the mound. The ball didn’t carry, the indoor lighting was poor, and the sizable amount of foul territory (26,900 square feet, according to researcher Andrew Clem) gave pitchers a healthy number of cheap outs. When the Dome opened with a 1965 exhibition game against the Yankees, New York pitcher Mel Stottlemyre said, “This ought to be a pitchers’ paradise. The ball just doesn’t carry the way it does outdoors. You’ve really got to hit one to knock it out.”

The Astrodome rated as a pitchers’ park in each of its 35 seasons, with park factors ranging from a low of 91 in the mid-1970s to a high of 98 in its final season of 1999. The park’s extremity probably altered the course of franchise history, as it caused the Astros to undervalue homegrown superstars Joe Morgan (120 OPS+ with Houston) and Jimmy Wynn (131 OPS+) because of their low batting averages (.255 and .261, respectively). In the early ’70s the Astros traded both men for underwhelming returns.

The quintessential Astrodome game was played in 1968, the Year of the Pitcher, when the All-Star Game came to Houston. Four Hall of Famers (Don Drysdale, Juan Marichal, Steve Carlton and Tom Seaver) took the mound for the National League, helping the NL to a 1-0 victory in which it allowed just three hits and no walks. Fittingly, the game’s lone run scored in the least hitterly way possible: Willie Mays singled, advanced to second on an error, went to third on a wild pitch, and scored on a ground ball double play.

Baker Bowl (Phillies, 1887-1938)

The longtime home of baseball’s least successful franchise, Baker Bowl housed the Phillies for 52 years, 40 of which saw them finish in fourth place or worse. It was a notoriously ramshackle structure, with the bleachers collapsing during games in both 1903 and 1927. Between them, the two incidents killed 13 people and injured dozens. Locals called Baker Bowl “The Bump” because a railroad tunnel running underneath the outfield caused a bulge in the playing surface.

The stadium’s most arresting feature, however, was its massive right field wall, which famously featured a huge ad for Lifebuoy soap. The wall was 60 feet tall and around 200 feet long, and at 273 feet away from home plate, it was an appetizing target for hitters. (And possibly a nuisance for infielders: “If the right fielder had eaten onions at lunch, the second baseman knew it,” Red Smith quipped in the New York Times.) Gavvy Cravath, a right-handed slugger who rejected the Deadball Era’s slap-hitting ethos, became so adept at knocking opposite-field fly balls over the fence that he became, for a brief time, baseball’s modern career home run leader. In 1933, the inviting fence helped the Phillies’ Chuck Klein win the National League Triple Crown.

Forbes Field (Pirates, 1909-70)

The longtime home of the Pirates was essentially a neutral ballpark — its batting park factors ranged from 95 to 107 — but it was a perennial hotbed for that most exciting of baseball plays, the triple. In their 62 years here, 13 times the league leader in triples was a Pirate.

Instead of the padded, gently curving outfield fences of today, Forbes boasted a series of straight brick walls which changed direction at hard angles. The stadium also featured a confusing mishmash of ever-changing wall heights. At various times, the heights of different parts of the wall measured 8, 9, 10, 12, 14, 17, 18, 24, 25, 27, 28, and 32 feet tall, turning deep fly balls into adventures for even the most talented outfielders.

Only 11 teams in modern baseball have ever hit 110 triples in a season; six of them were Pirates teams that played at Forbes Field. In 1912, an obscure Pittsburgh outfielder named Owen Wilson hit 36 three-baggers in one season, far more than any big leaguer before or since. The personnel didn’t even seem to matter much: Between 1923 and 1930, seven different Pirates players led the league in three-baggers. “It’s a triple ballpark, not a homer ballpark,” said Pie Traynor, who led with 19 in 1923. “Hitters shorten their swings.”

Huntington Avenue Grounds (Red Sox, 1901-11)

In 1901 the American League, which was trying to jump up to major league status, appointed a blue-ribbon panel — chaired by A’s manager Connie Mack, a Massachusetts native — to explore Boston and select the perfect site for a new ballpark. They picked a grassy field in North Roxbury where the circus usually set up when it came to town. “There was a fairly large pond on the property that children would splash into during summer months,” Bill Nowlin wrote in his book Red Sox Threads. “In the winter, of course, people could ice skate there.”

Huntington Avenue Grounds, the site of the first World Series game ever played, was also notable for two other things. The first was a huge sloping embankment that started 50 feet in front of the left field fence, so fans could be seated on the playing field when there was an overflow crowd. The second was the impossibly vast size of its outfield. The power alleys were well over 400 feet away, and the center field distance has been reported anywhere from 530 feet (in the most conservative estimate) to a difficult-to-believe 635 feet.

Despite its distant fences, Huntington Avenue had a mostly neutral effect on offense, though the ballpark did drastically alter the shape of that offense. The park greatly reduced the number of doubles, because hits that would have been doubles elsewhere instead bounced all the way to the wall for triples and inside-the-park homers. According to SABR’s Ron Selter, Huntington’s park factor for doubles in its earliest configuration was 78, compared to 156 for triples and 139 for home runs. Of the 158 total homers hit during the park’s first four seasons, only four went over the fence — this despite the Red Sox boasting the batter who reputedly hit the longest fly balls in the league, Buck Freeman.

Lake Front Park (Cubs, 1878-1884)

This elaborate wooden ballpark, boasting 18 curtained luxury boxes and a fancy pagoda-style bandstand at its main entrance, was the home of the Chicago White Stockings (today’ Cubs franchise) for seven eventful seasons. It stood on the same piece of prime downtown real estate where the famed Anish Kapoor sculpture known as “The Bean” now stands.

Because the ballpark site was hemmed in by train tracks and Lake Michigan to the east and Michigan Avenue to the west, its outfield distances were the shortest in baseball history. Lake Front Park’s foul lines were a comical 180 feet to left field and 196 to right, and during most seasons balls hit over the left field fence counted as ground-rule doubles. In 1884, when they counted as homers, four different Chicago batters broke the major league home run record, led by Ed Williamson’s 27. (And you thought the 1998 Sosa-McGwire home run race was a big deal.)

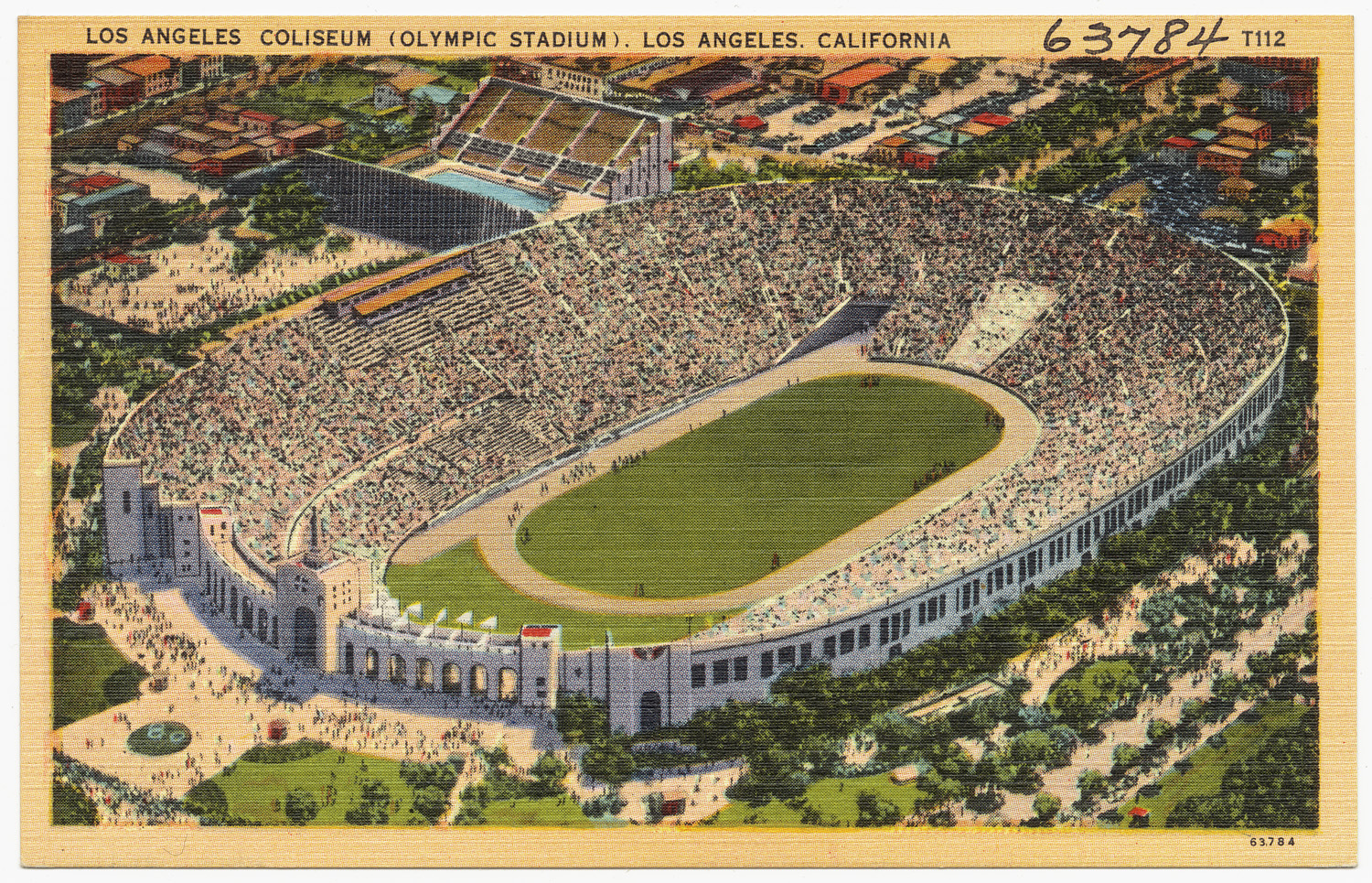

Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum (Dodgers, 1958-61)

Photo: Boston Public Library

Forced to choose from several less-than-perfect venues to use temporarily while Dodger Stadium was being built, Walter O’Malley picked the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum as his team’s first home in California. The humongous concrete structure was already a historic landmark even then, having been built in 1923 for USC football and expanded for the 1932 Olympic Games.

The Dodgers soon discovered that it was quite challenging to play baseball in a football stadium. One pitcher called the Coliseum “The Grand Canyon with seats.” The playing field, a giant oval, was entirely the wrong shape for baseball, but O’Malley didn’t care. He was more interested in the Coliseum’s 93,000 seating capacity. The Dodgers squeezed a baseball field into the space by putting home plate at one end of the oval and situating the left field fence a tantalizing 251 feet from home plate. This pleased the team’s right-handed hitters, but to keep home runs from coming too cheaply, the Dodgers erected a 40-foot-tall chicken wire screen in left field.

Lefty sluggers like Wally Moon learned to hit pop-ups to the opposite field, where they would plop over the chicken wire for home runs. The bizarre configuration made a mockery of the game, and also curtailed the career of lefty pull hitter Duke Snider, but Angelenos loved it anyway. When the Dodgers played in the 1959 World Series, more than 92,000 people packed in for each of the three games at the Coliseum. Those remain three of the five highest-attended games in baseball history. The other two were also played at the Coliseum.

Polo Grounds (Giants, 1911-1957; Yankees, 1913-22; Mets, 1962-63)

Photo: Columbia University Library.

Like Forbes Field, the Polo Grounds had a neutral overall effect on offense, but the ballpark’s oddities dramatically affected the shape of that offense. The horseshoe-shaped grandstand surrounded an oval playing field which featured some of the shortest foul lines in history but also one of the deepest center field distances. The left field distance fluctuated over the years from 250 to 287 feet, while right field ranged from 249 to 258. Center field, meanwhile, was as distant as 505 feet during the 1930s and ’40s.

The short porches in left and right fueled some gaudy home run total for the home team’s hitters. Giants slugger Mel Ott hit 323 homers at the Polo Grounds, compared to just 188 on the road. When Babe Ruth ushered in the live-ball era in 1920 — exploding from one homer every 18.7 plate appearances to one every 11.4 plate appearances — his improvement was caused largely by leaving then-cavernous Fenway Park for the friendly confines of Coogan’s Bluff.

The dual effects of the Polo Grounds were dramatically illustrated during one of its most famous games, Game One of the 1954 World Series. With two runners on base in the eighth inning, Cleveland’s Vic Wertz clubbed a 440-foot drive that famously landed in the outstretched glove of Willie Mays. Two innings later, Giants pinch hitter Dusty Rhodes hit a meager pop fly down the right field line that barely squeaked over the wall 258 feet away for a walk-off homer, causing pitcher Bob Lemon to throw his glove down in frustration. “Lemon’s glove went further than my home run,” Rhodes quipped.

Stars Park (St. Louis Stars, 1922-31)

Photo: Missouri Historical Society.

For a brief period during the 1920s, the St. Louis Stars were one of the greatest teams in baseball, and in 1922 they became one of the few Negro League clubs ever to build their own stadium. Constructed for just $38,000, Stars Park was a workmanlike, no-nonsense structure with a small wooden shack out front which served as the ticket office.

Stars Park’s most notable characteristic was the “car barn,” a pre-existing repair shed for the city’s trolley cars. The shed formed part of the left field wall, and it was an inviting target for batters who tried to hit the ball onto its roof for easy home runs. “Down the line was 269 feet,” Stars outfielder Cool Papa Bell once recalled. “If a right-hand hitter could pull the ball he could hit it up on that shed, but they had to hit it high—about 30 feet high. The car shed was the wall.”

Bell was no home run threat, but his right-handed teammates — especially hitting prodigies Mule Suttles and Willie Wells — became adept at lofting fly balls onto the roof of the shed. By one count Wells hit 27 homers in 88 official league games in 1929, reputed to be a Negro Leagues single-season record. Long balls were so prevalent that during some years, balls hit onto the trolley shed were considered ground-rule doubles. Aided by their friendly home ballpark, the Stars slugged their way to Negro National League pennants in 1928 and 1930.

South Side Park (White Sox, 1901-1910)

Photo: Library of Congress.

“South Side Park was the all-time number one pitcher’s park,” Michael Benson wrote in Ballparks of North America. “The outfield fences were irregularly shaped, dipping in toward the plate in straightaway center. The home run distance was shorter to center than to right or left, but practically unreachable in all directions.” This pitcher’s paradise, home to the White Sox during the first decade of the 1900s, was an oasis for Big Ed Walsh, the Sox hurler whose 1.82 career ERA remains baseball’s all-time best mark. A total of two home runs were hit at South Side Park in 1904, three in 1906, and four in 1909 — and yes, that includes both inside- and outside-the-park homers.

In 1906 the ballpark’s paralyzing effect on offense caused the World Series-winning White Sox to be misleadingly dubbed the “Hitless Wonders.” On the surface it seemed an accurate moniker, since the Sox batted just .230 as a team with a .588 OPS. However, thanks to judicious use of the stolen base and the sacrifice bunt, Chicago was able to manufacture 3.68 runs per game, actually a smidgen better than the league average of 3.66. The Sox kept up that rate in the World Series, scoring 3.67 runs per game while pulling off what remains the biggest World Series upset of all time, dismantling the 116-win Cubs in six not-particularly-competitive games.

References and Resources

- Baseball-Reference

- Clem’s Baseball

- Boston Globe, various years

- New York Daily News, various years

- San Francisco Chronicle, 1914

- Michael Benson, Ballparks of North America

- Eric Enders, SABR Biography Project, “Buck Freeman”

- Fadeaway Podcast, “Nine Reasons”

- John Holway, Voices From the Great Black Baseball Leagues

- Philip Lowry, Green Cathedrals

- Angus McFarlane, foundsf.org, “Ewing Field”

- Bill Nowlin, Red Sox Threads

- Dan O’Neill, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, “Historic photo revives interest in Negro League’s St. Louis Stars”

- SABR Biography Project, “Baker Bowl”

- SABR, Dome Sweet Dome: History and Highlights from 35 Years of the Houston Astrodome

- Ron Selter, SABR Biography Project, “Huntington Avenue Grounds”

- Curt Smith, SABR Biography Project, “Forbes Field”

This was just added to my “Favorite Articles 2018” folder. Great job and I look forward to the reading the book!

If you had a time machine, which of these stadiums would you most have wanted to see a game at?

Thanks for the kind words, Eric. I would choose Stars Park, partly just to see what it really looked like, since no photos exist of the interior. (The outside photo shown in the piece is the only photo of the park that exists.) But it would have been incredible to actually sit In the stands and soak in the atmosphere of a Negro Leagues game.

“In 1912, an obscure Pittsburgh outfielder named Owen Wilson hit 36 three-baggers in one season, far more than any big leaguer before or since.”

Wow

Absolutely love this. I love the history of the game and I love the old parks most of all. Maybe my personal favorite is the Union Grounds in Brooklyn, which had a pagoda in play in deep centerfield.

Do you know why Gibson didn’t pitch for the NL in that ’68 All Star Game at the Astrodome?

Yes, Cardinals manager Red Schoendienst was also the All-Star manager that year, and he decided to hold Gibson out of the game with a phony injury that was labeled “arm tightness.” Gibson at the time was on a streak of 9 complete games in a row. He pitched a complete game three days before the ASG and would pitch another one three days after the ASG. He was probably just tired and didn’t feel like wasting innings on an exhibition.