MLB Turned a Blind Eye to Bobby Cox’s Domestic Abuse

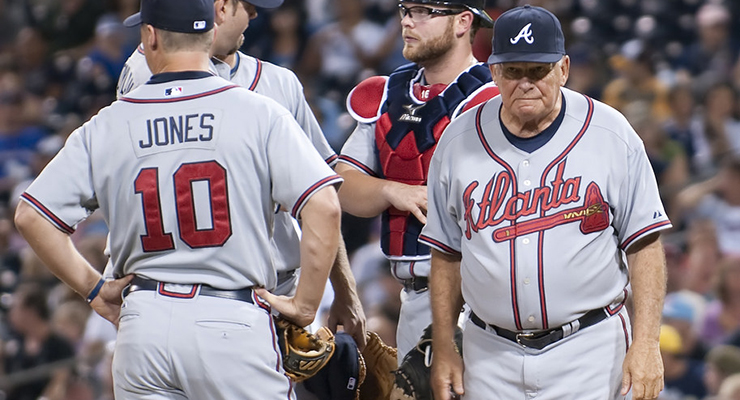

Bobby Cox had a domestic incident with his wife Pamela in 1995 that went unpunished. (via Dirk Hansen)

Editor’s note: This article contains descriptions of domestic violence.

Bobby Cox is known for a lot of things: managing the Atlanta Braves for what seems like an impossibly long time (in reality, it was 26 non-consecutive years), being inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame, holding the record for most managerial ejections (158).

What isn’t often talked about when we talk about Bobby Cox’s legacy is domestic violence, but perhaps it should be. Cox is just one in a line of men Major League Baseball chooses to celebrate for their on-field accomplishments while overlooking or forgetting about their off-field violence against women. The reference to his domestic violence incident with his wife is even conspicuously absent from his Wikipedia page.

In 2016, MLB has taken domestic violence more seriously than it has before. The season saw the suspensions of Aroldis Chapman, Jose Reyes, and Braves player Hector Olivera for partner violence under its new policy, enacted before the season began.

Tony Clark, executive director of the Major League Baseball Players Association, said in a statement: “Players are husbands, fathers, sons and boyfriends. And as such want to set an example that makes clear that there is no place for domestic abuse in our society. We are hopeful that this new comprehensive, collectively-bargained policy will deter future violence, promote victim safety, and serve as a step toward a better understanding of the causes and consequences of domestic violence, sexual assault, and child abuse.”

The policy allows players to be suspended if they are arrested for domestic violence (after the incident is investigated by the league), even if the case is never prosecuted and the player is not convicted of the offense. This is significant, because many victims of domestic violence will choose to drop charges or refuse to testify against their abuser, meaning many perpetrators never face convictions or consequences for the abuse. Per the policy:

Investigations:

The Commissioner’s Office will investigate all allegations of domestic violence, sexual assault and child abuse involving members of the baseball community. The Commissioner may place an accused player on paid administrative leave for up to seven days while allegations are investigated…Discipline:

The Commissioner will decide on appropriate discipline, with no minimum or maximum penalty under the policy.

Players are able to challenge any decisions to the arbitration panel.

But before Chapman and before Reyes, there was Bobby Cox. In 1995, Cox was arrested on simple assault charges against his wife, Pamela. According to police reports, Pamela Cox called police to their home after, she said, Cox punched her in the face and pulled her hair during an argument. She also said that Cox called her a “bitch.” The police report noted that Pamela Cox’s face was red at the scene. Cox was released from jail later that night on $1,000 bond.

What happened after the incident, during damage control on the part of Cox and the Braves, epitomizes so many misconceptions about domestic violence and the way victims of it behave. Later that week, Bobby and Pamela Cox sat side-by-side during a press conference (much like NFL player Ray Rice and his wife, Janay, did after the video of him assaulting her was made public), and told the media that it had all been a big misunderstanding. Both parties denied that there had been any physical violence whatsoever, and attributed Pamela’s red face to the fact that she had been crying. Cox painted the incident as a simple argument that had gotten a little too heated, and his wife supported his account.

If my 10 years as a domestic violence counselor taught me anything, it’s how to identify abusive behavior, even when it’s subtle. I trained in how to spot signs of abuse. I spent hours hearing story after story from the women I worked with, whether I was their therapist, a staff member at the emergency shelter they had fled to, or the voice on the other end of the hotline they were calling to seek help and guidance. All these were roles I held over the course of my career as a social worker.

Despite his best efforts, Bobby Cox’s statements told a different story than the one he was trying to sell to the public. “There was no hitting of any sort. I grabbed her forehead and her hair a little bit just to keep her a distance away from me and we were both going at it pretty good,” Cox said. He also gave this version to the police, as the report said that he admitted to pulling her hair and calling her a name. What Cox fails to realize is that grabbing someone’s forehead and hair is an act of violence, and calling the person a name is verbal abuse. In his attempt to defend himself from accusations of abuse, he actually admits to being abusive.

What’s more, he also tries to shift the blame onto Pamela, indicating that they were both the aggressors in the situation. According to the police report, he claimed “that she also has been violent in the past, and that he hit her in reflex to her assault on him.” This is a classic tactic used by abusers; in fact, when victims are aggressive it’s usually an attempt to protect themselves from the abuse being perpetrated against them.

The police report further indicated that “(Pamela Cox) stated that this has occurred many times before, but (she) never called the police because of possible media attention” and the effect on their children. Again, this is textbook domestic violence. The incidents are not isolated; they are part of an ever-escalating pattern of abuse and have often been going on for quite some time before the police ever become involved.

Also concerning is the fact that the police report mentions that their then 13-year-old daughter was home and witnessed the assault. An abuser is often comfortable enough with his behavior to be doing it openly in front of the kids, and it is another way to exert control over family members, cultivating a culture of fear in the house.

According to Lundy Bancroft’s book When Dad Hurts Mom: Helping Your Children Heal The Wounds of Witnessing Abuse:

Researchers tell us that three-quarters of children living with violent men are physically present for at least one assault. Some mothers report that weeks or months after a scary abusive event, their children suddenly mention details of what happened that the mother had idea the child had witnessed. They watch through doorways or cracks, they stand at the top of staircases, they hid behind furniture. Sometimes they are right out in the open.

We, of course, have no way of knowing how many times their daughter witnessed the abuse, but if it was indeed ongoing, research tells us that she not only saw it, but was affected by it in both large and small ways.

Pamela Cox indicated that she had not wanted Bobby to be arrested, that she had no intention of pressing charges. Janay Rice also dropped the charges against Ray, as did Chapman’s and Reyes’ partners. It’s incredibly common for victims to decide not to press charges against their abusers (or refuse to testify, if the state decides to pursue the case), and it absolutely does not indicate that the abuse did not happen. A study in the journal “Social Science & Medicine” found that “emotional appeals from their abusers who minimize their own wrongdoing, rather than threats, often lead victims of domestic violence to drop charges.”

ThinkProgress reports:

There are various reasons victims choose not to do testify in domestic violence cases, including the fact that reliving the experience can be embarrassing and even re-traumatizing. One of the biggest reasons they avoid court, though, is the fear of retribution from their accusers, that testifying will only further jeopardize their safety… and then there is the aspect of how they are often treated by law enforcement officials who ask the wrong questions or don’t always take the claims seriously. That can be especially true in cases involving celebrities or famous athletes who invite more media attention to a case.

One look at the National Center on Domestic and Sexual Violence’s Power and Control Wheel shows almost all the behaviors identified in the police report or the press conference. They include: saying the abuse didn’t happen, shifting the responsibility for the abuse by saying she caused it, calling her names, and making her drop charges, as well as the physical violence that he demonstrated. Bobby Cox’s incident checks all these boxes.

One look at the National Center on Domestic and Sexual Violence’s Power and Control Wheel shows almost all the behaviors identified in the police report or the press conference. They include: saying the abuse didn’t happen, shifting the responsibility for the abuse by saying she caused it, calling her names, and making her drop charges, as well as the physical violence that he demonstrated. Bobby Cox’s incident checks all these boxes.

If we are to believe that the incident happened as indicated in the police report (and I do), why don’t most people even remember that Bobby Cox was accused of domestic violence (though it doesn’t surprise me that the man who holds the record for ejections has a temper at home, too)?

It’s probably because despite Cox’s arrest, he faced no consequences from the Braves. He went on the manage the rest of their season and the club’s general manager at the time, John Schuerholz, told the media that he did not see any need for Cox to take any time off. The club chose to make it a non-issue, MLB chose to make it a non-issue, and his wife did what she could to make it a non-issue. Everyone involved likely hoped that downplaying the incident would make it go away, which it essentially did. Bobby and Pamela are still married, which isn’t surprising. A Time magazine article showed that there are plenty of reasons that people stay in abusive relationships, chief among them that they may be financially tied to their abuser and feel stuck; they may fear losing custody of their children; they really do love their abuser. And then there’s this:

It can be dangerous to leave an abuser because the final step in the domestic violence pattern is to kill the victim. Over 70% of domestic violence murders happen after the victim has left the relationship.

This strategy of trying to make domestic violence allegations disappear was not unique to Cox. It was the go-to strategy for Major League Baseball until this year. We saw it happen with Kirby Puckett, Josh Lueke, Brett Myers and Pedro Astacio, among others. Myers and Astacio are notable for the fact that both started in the first game following their incidents (Myers’ was the very next day and Astacio’s was Opening Day of the following season).

And while 2016’s domestic violence policy and player suspensions are a wonderful step, it’s worth noting that both Chapman and Reyes played or are playing for their respective teams in the playoffs this year — something they would not have been allowed to do if they had been found guilty of using performance enhancing drugs like Marlins infielder Dee Gordon was. It seems to me that baseball still finds taking drugs to help you be better at your job to be a more serious offense than landing a woman in the hospital. For his part, Bobby Cox had his number retired by the Braves and was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2014.

If baseball is really ready to take domestic violence seriously, as it says it is, we need to ask ourselves why players and managers are able to get by unscathed. Should a “mistake” (as so many players like to refer to domestic violence incidents as) tarnish an athlete’s entire reputation? Should he be ineligible for things like starting playoff games or Hall of Fame induction? For survivors of domestic violence like me, the answer is clear. I’m triggered and sad every time I see a player’s face on the TV screen, knowing the kind of violence he is accused of. Not only that, just because someone is arrested only one time for domestic violence does not mean it was a one-time thing. In fact, the biggest predictor of future violence is past violence. It’s likely that it’s happened before, and it will happen again.

Bobby Cox may have been a great baseball manager. But he is also very likely an abuser. When we talk about the former, we need to remember to give equal weight to the latter.

References & Resources

- John Beamer, The Hardball Times, “Cox breaks ejection record”

- Jason Linden, The Hardball Times, “Baseball Cannot Tolerate Violence Against Women”

- Fox Sports South, “Hector Olivera suspended 82 games for violating MLB’s domestic violence policy”

- Paul Hagen, MLB.com, “MLB, MLBPA reveal domestic violence policy”

- Associated Press, San Francisco Gate, “Braves Manager Jailed — He and Wife Deny Assault”

- Lundy Bancroft, When Dad Hurts Mom: Helping Your Children Heal the Wounds of Witnessing Abuse, 2004

- Travis Waldron, ThinkProgress, “Why Victims Of Domestic Violence Don’t Testify, Particularly Against NFL Players”

- Jim Leckrone and Mary Wisniewski, Reuters, “Study shows why domestic violence victims drop charges”

- National Center on Domestic and Sexual Violence, “Power and Control Wheel”

- Eliana Dockterman, Time, “Why Women Stay: The Paradox of Abusive Relationships”

- Mike Bates, SB Nation, “MLB’s record on domestic violence worse than NFL’s”

Britni, Wonderful article and you do a great job of applying your personal professional experience to a VERY sensitive topic.

Applying current mores though to an event 20+ years old though strikes me as the equivalent of minimizing George Washington, et. al because he owned slaves. Certainly wrong by current standards, and worth remembering, but to “apply equal weight” to the memory seems extreme.

What would you expect baseball to do in 2016? Kick Bobby Cox out of the Hall of Fame?

I could be wrong, of course, but I don’t think that was the point of the article. I don’t think she’s advocating to punish Bobby Cox right now for something that happened 20+ years ago, but rather to bring attention to the incident, and then use that as a way to talk about the evolving policy and moving forward.

Domestic abuse 20 years ago was like owning slaves in George Washington’s time? Where the hell did you get that idea? so 20 years ago i walk up to you and casually talk about beating my wife, grabbing her hair shouting her etc and you just nod and accept it? it’s not similar at all! Slavery in Washington’s time was deemed socially acceptable and common domestic abuse was a crime 20 years ago, don’t go equating the two.

I think the key point being driven at here is if you’re going to evolve in how you deal with these cases you need to look at the mistakes of the past and show that they can be high profile and things need to change. Think on Barry Bonds what would the layperson know about him. Home run king then Steroids (never proven only allegations). Bobby Cox doesn’t have domestic abuse near his memory or legacy is that fair? are they being treated the same way? I’m a cubs fan and i felt both Chapman and Reyes should have been ineligible for postseason play, if there’s real life tangible impact on earning and careers the message that mlb cares will be there all the more

I actually had no idea about Bobby Cox doing this. I’m left wondering what a good, proactive policy might look like from MLB, given that it seems from what I’ve read that suspensions (in essence taking away a player’s living) without additional resources could actually exacerbate domestic violence situations. (Though I agree that players should not just have it swept under the rug as the author mentions.) Maybe a more victim-focused program that offers free and anonymous help for players’ victims would be a good start? I don’t know the answers, but would like to see MLB be thoughtful about this in a way that’s focused on solutions rather than PR.

All they CAN concentrate on is PR. That is how this behavior affects their business. What is Microsoft’s domestic abuse program, Walmart? No one knows, or cares because it doesn’t affect their corporate image,

Retired man, generally out of public spotlight, and still his wife, and you stir this up?

No proof of anything, and all this article does is make soft excuses for it.

Tell me, in the 20 years since, has there ever been an additional whiff of this behavior? You say it’s not a one time thing, yet perhaps I’m missing something as I’ve never heard of any even rumors of further allegations.

I guess you’ve the right to say he’s a likely abuser, but I’ve the right to say this is a cheap click-bait hack job. Enjoy your 15 minutes.

There is proof; he basically admitted what he had done. Did you read the article? It’s not really disputed that he committed what would be known as abuse.

But I’m not sure how much MLB or any sports league can do. If the person is an abuser, will suspending him from a playoff game make much difference? Keeping him out of the Hall of Fame isn’t going to change the basic issues involved. Presumably, people who use PEDs, once they get caught and suspended, will likely change their behavior (although, obviously, not all do). Certainly, the Braves/MLB should have at least suspended Bobby Cox, but would that have changed his behavior? It seems to me that a lot is being put on MLB (and the NFL) to address a widespread social issue that has complex sources and causes. And, certainly, sports leagues can’t police marriages.

I’ll echo the statements above.

I don’t want to condone Cox’s past behavior (it was and still is indefensible) but what is the point of this article? His legal history is pretty well-documented and it just seems like dragging someone’s name through the mud because it’s a slow news day.

Matt Bush ran over a dude’s head and left him for dead on the side of the road and has been called an inspiration this season.

Legions of players from earlier eras were vehement racists.

Having the skills/abilities to thrive in baseball and being a good person aren’t even remotely related.

If we’re going to address the problem and hold the league to a higher standard, why are we focusing on the past? Shouldn’t we be examining the current landscape of the game for changes that can be made?

Gonna be honest, already regret commenting on this. Domestic abuse is clearly wrong and a major issue in the world of professional sports. The league has a history of ignoring it and siding with the players across the board.

I’m a knee-jerk Braves fan who doesn’t want to hear that about Cox but it’s an unfortunate reality of his past.

Note to self: don’t comment immediately after reading something. Let it sink in for a bit.

I get why it is important to pose the question, because if his wife was never incentivized to call the cops or seek help again, nobody could ever know what really goes on behind closed doors. We are forced to take their word that everything is fine, though all the research and evidence out there indicates “once an abuser, always an abuser.” MLB can investigate all they want, but many victims feel safer with the status quo than the alternative, so every instance turns into a witch hunt. It is much easier to glorify celebrity than to protect someone who may or may not be a victim… all it takes is for one “victim” to be full of shit and public perception is changed to support the “innocent until proven guilty.”

The takeaway I get is that time is what can truly change the narrative, and nobody is going to get too bent out of shape over what can only be proven to be one instance of poor judgement.

As long as Aroldis Chapman and Jose Reyes are playing, I will never believe that MLB wants to curb this shit. Seriously, be done with these assholes who hit women and move along. Baseball will be better because of it.

It’s a well written and well thought out article, until the end.

You point out that just because someone is arrested once, it doesn’t mean it only happened once. And you’re right, it doesn’t.

But you clearly imply that anyone who is arrested for any sort of domestic violence once is a habitual abuser. And that’s just as wrong, if not more so, than assuming that the one arrest was the only incident. You’re painting a pretty detailed picture of someone based solely on one incident, and not only that, you’re using a very broad paintbrush to paint a lot of people as something.

One documented incident doesn’t mean it’s the only incident, that’s for sure, but it also doesn’t mean it’s not, and you crossed the line.

This post was clearly needed. So much disgusting victim-blaming in these comments. Wow. I can’t believe how pro-domestic abuse the Hardball Times commenters are.

This is disgusting. Domestic abuse is wrong, period.

The long slow crawl through the institutions continues apace. There isn’t much left.

I’m not going to try to engage or change the minds of those on this thread that are clearly trolling and victim-blaming, but will just say that it’s disgusting and has no place in baseball or anywhere else. Shame on you and please get help.

Needed click bait for today?

Philip — all of what you wrote is stupid, but my guess is you don’t care. Instead, I’ll point out that you do a fantastic job of touching on different parts of the abuse graphic:

“This article is junk” — Intimidation

“It pains me to see Britni spelled with an i more than seeing Chapman and Reyes on the field” — Emotional abuse

“Abuse sucks, but demonizing baseball players isn’t going to stop it” — Minimizing, denying and blaming

“Corporations only care about the bad PR. Not the actual issue” — Economic abuse

“Ultimately domestic abuse takes two. Like MLK said, a man can only ride your back if it’s bent. Get some spine” — Minimizing, denying and blaming

On your next post, please try to hit the others…

“What’s more, he also tries to shift the blame onto Pamela, indicating that they were both the aggressors in the situation. According to the police report, he claimed “that she also has been violent in the past, and that he hit her in reflex to her assault on him.” This is a classic tactic used by abusers; in fact, when victims are aggressive it’s usually an attempt to protect themselves from the abuse being perpetrated against them.”

OK, so you’ve established that both victims and abusers can be aggressive. This makes sense: of course a victim is going to fight back sometimes.

“What Cox fails to realize is that grabbing someone’s forehead and hair is an act of violence, and calling the person a name is verbal abuse.”

Wait? Now you’re implying that only abusers can apply force. So when Pamela was alleged to apply force, you conclude that she must be doing so as a victim in self-defense, but when Bobby is alleged to apply force, you conclude that he must be doing so as an abuser.

That is incredibly poor reasoning from someone who is trained to spot signs of abuse: you cannot differentiate between abuser and victim and you simply guess based on stereotypes.

Well, c’mon. Isn’t it more likely that the stronger person (generally the male) is the abuser rather than the weaker? I realize that women can be violent themselves, but it seems much more likely that any force Pam used was in response to what Bobby was doing.

Female on male physical abuse is a real thing. There are examples of serious beatings, not to mention rapes. Men generally do not like admit when it happens and society tends to think it funny, so it does not get reported much. True, male on female is more prevalent but female on male is more common than you think.

Chuck Finley comes to mind.

Nowhere in your article do you provide any proof that the MLB “turned a blind eye” in its investigation of the incident. The article goes on to become borderline libel. You say it is “not surprising” that Pamela has been married to Bobby for over 20 years, and then immediately go on to list reasons she might have – including fear of being murdered. You go on say that based on an arrest over an incident we know little about from over 20 years ago that Cox is “very likely an abuser.” You even suggest that based on this incident, which Pamela came out and said was overblown the next day, that Bobby Cox should have been banned from the playoffs and the Hall of Fame, and that seeing Bobby Cox causes you to become “triggered and sad”.

I have worked in a public defenders offices before interviewing potential clients who are involved in domestic violence calls. Police often have to make an arrest if called for a “domestic” based on department policy. That does NOT mean someone there is a serial domestic abuser. Comparing this incident to the Ray Rice incident, which we have video for, is disingenuous. Hardballtimes lost a lot of credibility in my eyes after this article.

What an awful article. Other comments have touched on many of the problems with it already, but I want to reiterate how sloppy and sophistic most of this is. Very much an embarrassment to the rest of the content on THT.

It’s dressed-up in the armor of advocacy against domestic violence, which puts anyone challenging it at risk of being maligned as defending or justifying abusers. But if the same quality of reasoning and evidence used here were applied to baseball – or almost any other less-charged subject – I think we’d all see the rubbish for what it is.

Why the hell should MLB be giving the functional death penalty to people society doesn’t even bother to lock up for any length of time, if at all? Sorry you keep “getting triggered” every time anybody who has ever done anything wrong has any success in any endeavor.. no, actually I’m not, at all. Do your crime, do your time, and then make the best of yourself going forward. MLB is ALREADY punishing above and beyond the law.

“It seems to me that baseball still finds taking drugs to help you be better at your job to be a more serious offense than landing a woman in the hospital. “

This is actually a good point of discussion and I believe it is not as obvious as you think.

If someone was proven to have thrown a game, that player would be banned for life. The reason for this is this is a crime against baseball. The whole point of baseball is a physical competition where the outcome is decided on the field, and if this assumption is undermined it defeats the entire reason the MLB even exists and, possibly more importantly, why anyone would ever pay to watch. It is an existential crisis that deserves the most severe of punishments as the alternative is closing up shop.

PEDs are in a different classification. PEDs are banned not because they improve performance but because they are dangerous. It’s a health issue. If some players are allowed to use PEDs then it pressures everyone to use PEDs. Presumably, this will damage the quality of the product. While there are criminal elements here – at least some PEDs are illegal – it is essentially a crime against baseball. And if baseball thinks that something is damaging their game, then punishments are warranted. It may be that these punishments are insufficient or too severe, but that’s another issue.

Domestic violence is not a baseball issue. It is an awful thing, but barring it occurring in baseball facilities it is the same category with murder, drug dealing, burglary, car theft, fraud, and hundreds of other crimes that occur in society independent of baseball or any other sport. The problem here is there is a system to deal with these issues: the criminal justice system. That’s the reason why police and courts exist. If the person is found guilty, then criminal punishments are levied. Once the person has fulfilled those punishments, then the person has paid the debt to society and is presumably available to get a job whether that be in baseball or elsewhere.

So, yes, PEDs can very well be a more serious offense to the MLB than landing a woman in the hospital. That’s because it is a baseball organization. It polices what is relevant to baseball. In the criminal courts, putting a woman in the hospital is a lot more serious than throwing a baseball game because it is a criminal court.

What you are essentially advocating here is turning MLB into a parallel criminal court, which is an awful idea. If the MLB wants to punish players found culpable in criminal court, presumably because they are making the sport look bad, that’s a perfectly reasonable baseball decision. It should not be taking it onto itself to police actual crimes, given it is not qualified to do so and there is a qualified organization readily available. The MLB knows baseball. It should stick to that.

“PEDs are banned not because they improve performance but because they are dangerous.”

They’re supposely banned for both reasons, but there is a lot of hypocrisy touting the second. Many sports competed in clean–boxing for sure, maybe football–are more dangerous than taking PEDs, so the argument that PEDs pose health risks is used very selectively. And in fact when players like Bonds and Clemens can’t get voted into the HOF, it’s not because the voters think they encouraged other players to go fast and loose with their health, it’s because the numbers they put up were enhanced.

“What you are essentially advocating here is turning MLB into a parallel criminal court, which is an awful idea. ”

No, the point is that someone’s off-the-field behavior can impact baseball unfavorably, and baseball has the right to take steps to avoid this. As the author pointed out, many cases of likely domestic abuse don’t result in any kind of punishment, not because the man was clearly not guilty, but because he wasn’t guilty by a high enough standard to convince a court. There’s no particular reason why baseball should have to be held to the same standard. OJ wasn’t convicted, either, but would you want someone with that much evidence against him to go unpunished if he had happened to be an active ballplayer at the time?

Baseball is not just a profession. It puts a product out in front of the public. It has the right to exercise some quality control over that product.

So, yes, you want to turn the MLB into a parallel criminal court where players can be punished for alleged crimes that the criminal justice system may find frivolous but sound bad on the news, In addition, you want lower standards of proof, combined with a process that basically says the MLB can do whatever they want. What could possibly go wrong? You would not want to be employed under such a system.

The odds of an innocent man getting railroaded is high. You want bad PR? There’s bad PR! For that matter, you would not want to be the MLB the first time they get sued when someone challenges the ruling. The MLB will lose. The fact that the MLB effectively fined him $10 million dollars is not going to go well.

Given that OJ went through a highly publicized trial and was acquitted makes it rather difficult to justify that he is banned for life and won’t get paid the rest of his contract. I do appreciate that sports is entertainment and employing someone toxic is bad for business. I would avoid hiring people who would hurt my bottom line and would only bring in someone like OJ if I thought the benefits were truly great. However, a contract is a contract. They aren’t supposed to be easy to break.

Now that abusers can be suspended for sufficient evidence without a legal conviction, are victims going to be at higher risk of retaliation “for starting all this” even if they did very little?

Britni, do you know other examples of policies where abusers can be punished without any further involvement or “say-so” from the victim, and what the victims say about these?

Wondering if the league needs to do more about that, maybe make it clear they will have zero tolerance for retaliation.

Hey guys, do you ever see discussion about baseball that comes from, like, football fans or economists, who just don’t know much about baseball and don’t know what they don’t know? I understand it well enough, say the economists. Everybody has the right to an opinion, say the football fans.

Clearly the author and the people commenting have never met Bobby. I don’t want to share how I know him but I’ve been close to Bobby for 20 years. He made a mistake, that is true. Everyone deserves a second chance and he did not throw his second chance away. Britni suggests that he was abusive times before that, and he wasn’t. She also suggests that he probably was abusive following that incident, which he wasn’t. And with no evidence she said he most likely abused his child in some way. That could not be further from the truth. It infuriates me that she would make that claim and have zero support for it aside from “other abusers have”. Bobby is not an abusive man. He made a mistake and it was a bad one, but he learned from it and the family moved on. He loves his family more than anything. Everyone, including the author needs to find out more about the man he is before they pass judgment and make these false assumptions about him. He is a great man, father, and grandfather.

Are you in a position to address whether Bobby and his family ever underwent any counseling or behavior modification therapy as a result of the incident? I am in no position to debate Britni’s knowledge of this area; no doubt she is far better versed in the subject than I can hope to be, and I have no doubt her essay is well intentioned. But one thing the “once an abuser, always an abuser” stance she seems to take doesn’t appear to leave any room for is the possibility of rehabilitation and forgiveness. Perhaps Britni could address the prospects for modifying the abuser’s behavior. If the abuser admits he (or she, or they) has a problem and seeks help, does the modified behavior generally hold? I’m aware that alcoholics, for instance, understand that even if they’ve been sober for decades they’re still alcoholics. But abuse seems a little different somehow. Can abusers become model citizens with the proper help? And if they can, how long do they have to live with the stigma before we forgive them?

You have no idea what happened that night, and this article is irresponsible clickbait garbage.

The conundrum is that the Ms. De La Cretaz is probably right but it is possible she is not. What evidence do we need to take formal sanctions?

We have very good information at this point to strongly support all of her general statments about abuse and abusers. What documentation we have of the incident matches those patterns. We have evidence that Cox did something that can not be entirely written off.

However, without better evidence we can not KNOW the author is correct about how bad the incident was or that it was/is part or a broader pattern of abuse. The parties involved downplayed the incident and continue to act as if what happened was unfortunate but did not cross any critical line. That could be true. YMMV but there is room for doubt.

For criminal purposes we hold a very high standard – reasonable doubt. What doubt is reasonable is very difficult to pin down and there is room for reasonable people to disagree, but that is another discussion. We do that because the consquences of criminal guilt are, at least in theory, harsh. We want really, really good evidence.

For non-criminal purposes we do not have to have such a standard. You can set any standard of evidence you like for your own personal judgement. Standards for more formal judgement need to be prety high, though, because the consequences of formal judgements can also be pretty harsh. Losing your ablility to make your living in your chosen field or having your reputation sullied and losing otherwise deserved honors are significant penalties.

Is there enough evidence here to drag Bobby Cox’s name through the mud? Yup, there sure is. Is there enough evidence here to believe Ms. De La Cretaz? I am inclined to. But is there enough evidence that you must believe and, for example, kick him out of the Braves Hall of Fame? Nope, there sure isn’t.

Many of you will think I am misoginist scum and others a self-hating s**t head for those conclusions. OK. But it underlines how difficult these situations are. (Not to mention how hard it is to respect opinons very different from your own!)

The decision to print this was, as former POTUS George H. W. Bush was fond of saying, “Beyond the pale.”

“Have you no sense of decency?” Boston lawyer Joseph Welch to Wisconsin Republican Senator Joseph R. McCarthy, June 9, 1954. The immortal line that ended McCarthy’s career.

THT, “Have you no sense of decency?”

speaking from experience.

In an abusive relationship (yes it is a reality) the victim and perp. often change with situations and time. The emotions and personalities rule the situation and any addictions will fuel the battle. I witnessed events as a youngster that I swore I would never do as an adult… yet there I was 30+ years later being arrested.

Are you criticizing MLB because they started a domestic violence program? Cox may have been an abuser and MLB did little to nothing about it. But isn’t it better that today there is a program?

Actually I don’t agree with any program for social behavior that an employer publicizes. Employers CAN have a program, but how they enforce it is no one else’s business. If you disdain behavior, i.e. Cox, Kaepernick, etc. don’t support them, their teams, sport. Every individual can make that decision, if it affects the business, they will react, if it doesn’t affect the business, then society doesnt care as much as you think they do.

“Tell me, in the 20 years since, has there ever been an additional whiff of this behavior?”

You apparently have never attended a youth sports event attended by Bobby Cox where his daughter (and mine) played and heard Bobby screaming curses at the ref.

Metro Atlanta resident since 1990

I ran a red light 20 years ago. I hope the writer of this article doesn’t find out.

I’ll be labeled as a habitual abuser of the roads.

This is not a fair article without, you know, FACTS.

All there is, is blah blah opinion from the writer. No followup at all with the parties affected.

Drivel.

The real “blind eye” turned is by the author, who appears to have a rigid, biased, and inaccurate – if obsolete – perception of domestic abuse. Basically, she writes from the false pedestal that domestic violence is a man-against-woman crime, and she frames said violence to portray the woman as the always innocent, noble, and honest victim of these hateful male-perpetrated acts. Damn the facts – or better yet, manipulate, exaggerate, and re-construe them.

Example: “There was no hitting of any sort. I grabbed her forehead and her hair a little bit just to keep her a distance away from me and we were both going at it pretty good,” Cox said…In his attempt to defend himself from accusations of abuse, he actually admits to being abusive.

What’s more, he also tries to shift the blame onto Pamela, indicating that they were both the aggressors in the situation. According to the police report, he claimed “that she also has been violent in the past, and that he hit her in reflex to her assault on him.” This is a classic tactic used by abusers; in fact, when victims are aggressive it’s usually an attempt to protect themselves from the abuse being perpetrated against them.

Really? The author summarily dismisses Cox’s account, while summarily accepting and embellishing his wife’s account, essentially based on the justification “I’ve been doing this a long time and I just know these things.”

Cox’s account sounds sober and completely viable. Women are frequently violent abusers – both physically and verbally – yet society accepts, excuses, and even laughs at their behavior. After all, a man should just “be a man” and take it, right? Cox isn’t even allowed to protect himself or prevent his wife’s attacks because doing so would constitute abuse.

The reality is, abuse goes both ways. In fact, according to the CDC, more MEN suffer from domestic abuse (e.g. pushing, shoving, slapping) than women. When only considering severe violence (e.g. beaten, burned, choked, kicked, slammed with a heavy object, or hit with a fist), male victims still comprised 40% of all domestic abuse cases – a statistic that continues to shift away from women and towards male victims.

I find this article to be journalistic garbage well below the standard of THT, and, while I’m otherwise neutral regarding Bobby Cox, the author unjustly defames him here.

I may be echoing many other commenters, but I’ll still say my piece. I really do have concerns about domestic abuse and I don’t want MLB, or any other organization, to condone these actions. It may help keep players in check if they know that their livelihoods are on the line.

I can’t agree with the author’s assertions about Bobby Cox in this particular case. He’s been a public figure, a significant and notable one, for over 40 years. If there were even a whiff of another legal dispute or anything else to impugn his character, I would feel shame in supporting him. This is one time something happened over the course of his entire lifetime, it was 20 years ago, and there’s been no mention of any issues ever since.

I get that the author is an expert. I carefully read her words and I respect her knowledge. But this is a case where she has never spoken to either the victim or perpetrator, and in fact, has only scant information based on headlines. Perhaps if Britni had interviewed Pamela personally, or Cox’s daughter, or Cox himself, I might give her expertise the benefit of the doubt. But she’s extrapolating way beyond her ability to be certain in this case, given the minute data she has to work with, and she’s using those as a broad attack on Cox’s character. As a historian, I find her research to be shoddy.

I must ask why you chose to focus on Bobby Cox? There must be numerous cases of domestic violence involving players and managers over the last 100+ years. Is there something in specific you’d like to see happen him at this point?

Jesus Christ, did this end up linked on some garbage reddit thread? From under which rock did this MRA army emerge?

From the writer’s website (http://www.britnidlc.com/): “I believe in shattering stigma and changing the world through the power of storytelling.”