P.K. Wrigley and the College of Coaches

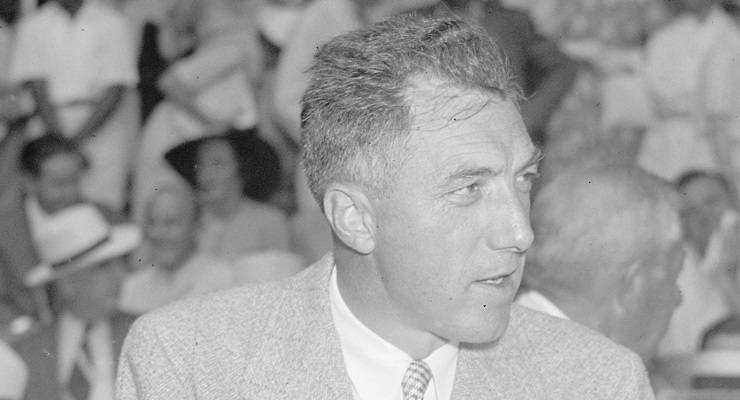

Future commissioner Ford Frick reluctantly approved the College of Coaches. (via Harris & Ewing Collection)

When Dan Jennings recently traded in his position as general manager with the Miami Marlins to become the team’s skipper, it raised more than a few eyebrows around baseball.

But throughout its history, the national pastime has had plenty of surprising managerial hirings.

None of them, however, sounded as bizarre at the time as the Chicago Cubs’ College of Coaches.

The concept was the brainchild of team owner Philip K. Wrigley, the chewing gum magnate who had lost patience with his team’s prolonged losing ways. The Cubs had just completed an abysmal 1960 season in which they’d gone 60-94, barely ahead of the last-place Philadelphia Phillies. Since the team’s last World Series appearance in 1945, Chicago had had only one season over .500.

It all started when manager Lou Boudreau, frustrated at Wrigley’s refusal to offer him a two-year contract, resigned during the 1960 World Series between the New York Yankees and the Pittsburgh Pirates.

At that point, Wrigley was eager to shake things up. Affectionately referred to as “P.K.,” he saw himself as a baseball visionary, one willing to think outside the box. Wrigley admitted that the selection of a manager was incidental to the broader problem of the bumbling organizational structure of the Cubs. Radical changes, he promised, were in order.

A panel was convened, composed of Wrigley, his son Bill, and team vice-presidents Charlie Grimm and Clarence “Pants” Rowland. Also part of the group was 33-year-old El Tappe, a player-coach with the Cubs in 1960. Tappe was regarded by many as the logical candidate to take over the managerial position.

The panel was come up with workable solutions to improve the inept Cubs. “We’re studying this thing from all angles,” Wrigley insisted.

Subsequent meetings followed, including lunch on Dec. 14 at P.K.’s private table in his posh restaurant at the Wrigley Building. As he sliced into his steak, the Cubs’ owner broached a topic that had been hot on his mind lately: Changing the title of “manager” to “head coach.” By way of explanation, Wrigley told how one night recently he’d looked up the word “manager” in the dictionary, and the definition he’d found was “dictator.”

“Heavens, we don’t need a dictator,” he told the panel.

Meanwhile, the winter meetings were approaching, and the Cubs were no closer to determining who their next manager — or “head coach” — would be.

But, Wrigley confided to the sportswriters, why does a team even need a manager, in the grand scheme of things?

After all, wouldn’t it be just as effective, nay, even better, to employ several coaches, and have them run the team like a board of directors? It was just an idea, of course, but still….

The more Wrigley talked about it, however, the sweeter he thought it sounded. Finally, at a press conference on Jan. 12, he dropped his bombshell: The Chicago Cubs would not have a manager for 1961. Instead, Wrigley proclaimed, they would have a “College of Coaches.” Before fielding the inevitable hard questions from the press, and trying to inject some humor into the situation, he’d placed a placard on the table in front of him, which read: “Anyone who remains calm in the midst of all this confusion simply does not understand the situation.”

The theory behind the College of Coaches, according to Wrigley, went more or less like this: Each of its members, or coaches, would serve as the Cubs’ nominal manager (or head coach) on a rotating basis. Initially, the College would be composed of Ripper Collins, Goldie Holt, Verlon Walker, Charlie Grimm, Tappe, Harry Craft, Vedie Himsl and Bobby Adams. Over the next several months, additional coaches would be brought in.

The key was that the coaches would alternately serve time in various positions throughout the entire organization. In the words of John Holland, the club’s vice-president in charge of player personnel: “(A member of the College) could spend the first month of the season as the head coach of the Cubs. The next month he may manage at San Antonio, and the month after he might manage our farm team at Wenatchee. Then he could come back to the Cubs in July or August merely as a coach.”

Wrigley reasoned that his plan would relieve the constant pressure on the Cubs head coach, whoever he may be. He had long believed that the indiscriminate firing of managers was the height of silliness, since it was hardly ever their fault when a team was underperforming. “We have made a study of managerial firings,” Wrigley proclaimed at the press conference, dramatically waving a sheaf of papers in the air. “It would surprise you. The list is staggering.”

Most importantly, the College of Coaches would take advantage of the diverse teaching methods, viewpoints, and opinions of multiple men, rather than just one, to more effectively nurture young players at all levels.

“If it works,” said Wrigley, “it’ll be a good idea. Managers are expendable. I believe there should be relief managers just like relief pitchers.”

He went on: “This is the day of specialists, and I think it makes good sense to get the best men for each individual job. They do it in football and it works quite well. I don’t see why it can’t work in baseball. We are not departing from tradition rashly or in haste, but rather only after long and thorough analysis.”

Baseball Commissioner Ford Frick, along with league presidents Warren Giles and Joe Cronin, gave reluctant stamps of approval. “If Mr. Wrigley wants to have eight coaches and no manager, then that is his business,” muttered Frick. Giles was even less enthusiastic: “Certainly Mr. Wrigley knows what he wants to do. But I’ve never heard of a team without a manager before.” Said Cronin, “I’d feel a lot better with one chief and more Indians.”

Bill Veeck, the owner of the cross-town Chicago White Sox, and a man noted for his outlandish promotions and stunts, didn’t like the sound of Wrigley’s concept. “This would be another case of divided authority, and I don’t think divided authority is a good thing. It then becomes confusing as to who is in the driver’s seat.” Veeck’s poo-pooing of the idea rings hollow, however. After all, he’d had no problems with divided authority back in 1951, when he came up with the idea of “Grandstand Manager’s Day,” in which fans made managerial decisions by holding up placards saying things like “steal,” or “bunt.” Veeck said he would never attempt a College of Coaches. “No, I’ll go along with tradition,” he said. “I guess I’m just an old stick-in-the-mud.”

Interestingly, it was Tappe, the player-coach on Wrigley’s original panel of experts, who may have first envisioned the rudimentary elements of the College of Coaches. Years later, Tappe, a catcher by trade, told his version of the story to Jerome Holtzman, the late, great Chicago Tribune sportswriter and official historian of Major League Baseball:

“Mr. Wrigley called me in because I was a holdover coach and asked what I thought they should do. I had been with the Cubs about five years. We had all those good, young arms, but every time we went to spring training, we had a new pitching coach. And I said, ‘We’ve got to systemize, to have stability.’ He bought that. I wrote an organizational playbook. He gave me extra money for that. We had the same signs, except for the keys, the same cutoff and rundown plays for all the clubs in our organization. When a player moved up, he didn’t have to learn anything new. We taught from kindergarten all the way through graduation. But I never mentioned anything about rotating managers. It was his idea.”

Not surprisingly, Wrigley’s College of Coaches was criticized from the beginning. The fans, the press and his fellow owners all chimed in to pan the plan. “Caveat emptor in tres partes divisa est,” wrote one irate Cubs minority stockholder (Which, translated, reads: “Let the buyer beware, or he’ll be cut up into small pieces.”). Apparently in 1961, chagrin was an emotion best expressed in Latin.

Himsl, a former minor-league pitcher, had the distinction of being the first “head coach” of the Cubs. He went 10-21 before giving way to Craft (7-9). Tappe (42-54) and Lou Klein (5-6) followed, as the Cubs finished 1961 at 64-90, a four-game improvement over the previous season.

As for the players themselves, not all were enamored with the system. Richie Ashburn, for one, made the glib observation in spring training of 1961 that it was “a nutty idea.” Following the season, the Cubs’ All-Star second baseman, Don Zimmer, said, “I can’t play under that many bosses.” Zimmer felt free to vent, now that he had been selected in the expansion draft by the New York Mets. “When you have so many managers giving so many different bits of advice to one ballplayer, what can you expect?” He added, “I don’t think any of my former teammates will be sore because I am saying these things. Next year when I’m with the Mets, I’ll look over at all my friends on the Chicago bench and feel sorry for them.”

Wrigley brushed off Zimmer’s analysis, saying, “We’ve had problems with him in the past. He has his ups and downs, just like anyone else. I don’t think Mr. Zimmer is the one who should be establishing our policies anyhow.”

Wrigley insisted that the program was working, particularly in the minor leagues. The predictable criticism of the College of Coaches, however, was its lack of stability. In the eyes of many, it appeared a hodgepodge saga, with nobody knowing who was really in charge at any point, anywhere. With the coaches shifting hither and yon and back between the majors and minors, from the North Side of Chicago to Carlsbad to Wenatchee to Houston, things got muddied. Different head coaches filled out different lineup cards, employed different strategies, and handled players differently.

More importantly, however, they also had their own agendas, and each may have been secretly gunning for the permanent managerial position, at the expense of his fellow coaches. Harmony was definitely not the byword at the corner of Clark and Addison.

Don Elston was a relief pitcher for the Cubs at the time. “It was Mr. Wrigley’s idea, so we had to live with it,” he said. “I can’t remember much that was good about it. There was jealousy among the coaches. They didn’t see eye to eye. When one guy was the head coach, some, but not all, of the other coaches did nothing to help him. They sat there waiting for their turn. It was an unhappy time.”

Apparently the only person who didn’t see all this coming was Wrigley.

The Cubs in 1962 were terrible. For the first time in the club’s storied history, they lost 100 games (103, to be exact). Only Zimmer’s first-year Mets finished with a worse record in the National League. Charlie Metro, who had assumed his turn as Chicago’s head coach beginning June 5, later accused Tappe and Klein of not “giving it their all.” Public accusations flew, including talk of hostilities between the various coaches. Metro finished out the season as head coach, but was later fired.

Too many cooks were not only spoiling the broth, they were making a mess of the kitchen. The future of the College of Coaches was very much in doubt.

Grasping for a solution, Wrigley decided to hire 43-year-old Robert Whitlow, a former Air Force colonel, to be the first athletic director in big league history, beginning Feb. 1. He would essentially run the organization from top to bottom, but when asked by reporters to define his duties, he was distressingly vague, saying only that he would “play it by ear.”

If Whitlow’s hiring wasn’t quite the death knell for the College of Coaches, it at least put it on life support. Two years into his grand experiment, perhaps Wrigley had decided that a dictator, even an inexperienced one, didn’t sound so bad after all.

There were rumors that Whitlow would eventually land the full-time managerial gig, but even Wrigley soon realized that he couldn’t simply hand the job to a baseball outsider. The fact that Whitlow was not well-liked by the players did not help matters.

And so it was that on the last day of February, 1963, Wrigley announced that 42-year-old former outfielder Bob Kennedy would be the sole head coach for at least the next season, and possibly beyond.

Under Kennedy, Chicago somehow managed to win 82 games in 1963. The Cubs stumbled the following season, finishing at 76-86. But Kennedy, looking more and more like a permanent manager, was brought back for 1965, although still with the title of head coach. After 56 games, however, with the Cubs near the bottom of the National League standings, Kennedy was booted upstairs, becoming the team’s new administrative assistant, while Klein, who’d been toiling in the organization’s hinterlands as a roving hitting instructor, took over as head coach. Chicago went 48-58 the rest of the way.

Then, on Oct. 25, 1965, the Cubs stole the headlines when they announced the hiring of Leo Durocher, the former Dodgers and Giants skipper who’d won three National League pennants, including a world championship with New York in 1954.

But what would Durocher’s title be? Head coach, or manager? Standing at the podium in the Wrigley Field press room (dubbed “The Pink Poodle” because of its odd color scheme), Durocher put to rest any doubts. “If no announcement has been made of what my title is, I’m making it here and now,” he boomed. “I’m the manager. I’m not a head coach. I’m the manager. You can’t have two or three coaches running a ball club. One man has to be in complete authority. There can be only one boss.”

And that boss would be The Lip.

When asked why he picked Durocher, Wrigley replied, “The primary reason is that he’s a take-charge guy.”

Indeed, the move represented a complete reversal in Wrigley’s thinking of how to run a ball club. Even at age 59, Durocher was as bombastic and strong-willed as ever, and there was no way he would share his authority.

Today, it is easy to poke fun at the College of Coaches, ridiculing it as just another laughable chapter in the history of a franchise that hasn’t won a World Series since 1908.

To be sure, it was a short-lived failure, particularly in the major league level, where stability and strong leadership are vital. But in the Cubs’ minor league system, the results were more positive. From the original faculty members, the College grew to include 24 different coaches at various times, including names like Whitey Lockman, Stan Hack, Alex Grammas, Mel Harder and Buck O’Neil. Even after Durocher’s hiring, Wrigley insisted that the revolutionary system was having an impact. “There never was a rotation of coaches except at the minor league level,” he explained, more than a bit disingenuously. “The rotation is principally designed for the minor league level to speed up development of the players and school them in the same pattern that is to be used with the Cubs. And this we will continue.”

Until his death in 1998, Tappe, the player-coach who claimed to have planted the seeds of the College of Coaches in Wrigley’s head, was steadfast in asserting that the philosophy deserved a better legacy. “Today, hitting and pitching coaches and infield coaches are moving from club to club, giving instruction to all of the players in their system. That was an essential part of Mr. Wrigley’s plan. That’s what we did.”

Without a doubt, Tappe insisted, Philip K. Wrigley was a man of rare vision.

It may have been despite the college of coaches, but the Cubs’ farm system flourished during that time. Players like Ken Hubbs, Don Kessinger, Ken Holtzman, Joe Niekro, and Glen Beckert eventually became the core of the contending Cubs of the late 60s.

Well, not Hubbs since he died in a plane crash in, I believe, 1963 or so. But your point is well taken.