The Future of Baseball Technology, Part Two: Into the Unknown

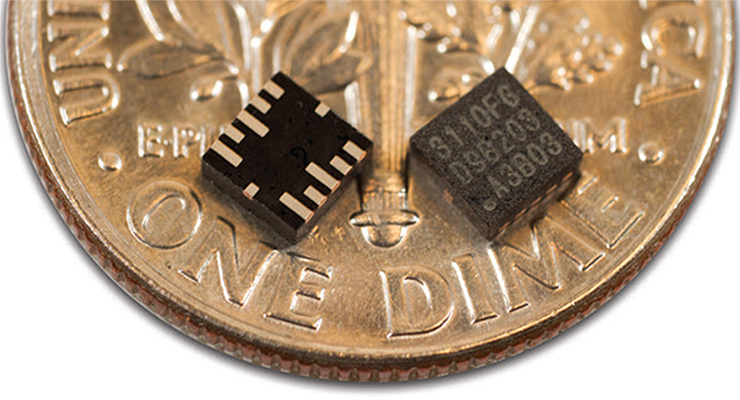

The mCube accelerometer is two millimeters wide, costs about a dollar and will revolutionize life over the next decade. (via mCube)

This is the second in a two-part series about how technology will shape the future of baseball. Part one can be found here.

Twenty years from now, baseball will probably look very similar to baseball today. Players will probably still use wooden bats, and wear helmets and uniforms that resemble what we have today, with updated designs, of course. Although the game will look visually similar, there will be an unseen side to the game which does not exist today. Technology will have become so small, powerful and inexpensive that it will be visually unnoticeable to the spectator. Every bat, ball, jersey and cleat will have embedded sensors, tracking data on the player’s movements, hydration, fatigue, blood oxygenation, muscle fatigue, and even mood and mental state.

Sound impossible? Scientists have already created “smart dust,” sensors smaller than the head of a pin. Researchers have created a transistor that is one atom thick. Google is working on a pill containing nanotechnology, which can detect cancer anywhere in the body. There is a man in the UK legally recognized as a cyborg. These are not common, everyday technologies yet, but neither was the microwave in 1965. Science-fiction-level smart devices are coming, and it will change life as we know it, baseball included.

In this installment, I will detail some of the more far-out technology that could shape the future of baseball on and off the field.

The Future of Wearables

The current generation of wearable devices are essentially high-tech pedometers, used to track how much activity a person does during the day. These are sleek, fun gadgets now, but will become much more powerful in the next few years. The next generation of wearables will be able to track things such as heart rate and blood oxygenation.

One example is the BSX Insight, a device worn on the calf by cyclists and runners. The device uses LEDs to shoot light into the muscle, then measures the reflection of that light. This allows for estimating the chemical composition inside the muscle. Thus, an athlete wearing this device can measure how fatigued the muscle is by seeing how much lactic acid is present.

“We shine light into the muscle several thousand times per second,” said Dustin Freckleton, co-founder and president of BSX Athletics. “That creates a real-time fingerprint of that athlete’s current physiology. We’ve taken what used to be a technology that used to only be found in laboratories, available with finger sticks and blood sampling, and democratized it so that it’s available in every athlete’s home gym without needles.”

Freckleton said athletes use this technology to take the guesswork out of training intensity.

“If you were a car, lactate threshold is your redline,” Freckleton said. “It’s not the highest you can rev your engine, but once you start going past it for long periods of time, it’s not good. Just as tachometer reads ‘1, 2, 3, 4, 5’ which are grades that show how fast the engine is turning, the human machine has states of intensity. It allows the athlete to dial in what intensities are needed to build the capabilities needed for the race they are training for. In a very real sense, they can learn ‘I need to speed up’ or ‘I need to slow down’ to be in the area where I am getting the most out of this workout.”

The BSX Insight team is focusing on endurance sports for now, but team sports will not be far behind. Imagine measuring the chemical composition of a pitcher’s forearm, bicep or shoulder in real time during a game. It could revolutionize pitching training and in-game pitching change decisions.

“We’ve already started experimenting,” Freckleton said. “Put (the device) in the right place, it could produce some real interesting results.”

In order for advanced wearable technology to be used by players at high levels, it needs to get easier to wear. Especially for devices that need to be worn on a pitcher’s shoulder, for example. DorsaVi is an Australian company that produces wearable sensors that stick to the athlete, rather than needing to be worn with a band or a sleeve. ViPerform is its sport product, which is currently made to be worn on the back and various parts of the leg.

“This level of analysis has never before been available outside the gym or biomechanics labs,” said Dave Wildermuth, CMO of DorsaVi. “ViPerform is allowing coaches and medical teams to screen athletes to provide objective evidence for decisions on return to play, measure biomechanics and provide immediate biofeedback out on the field, tailor and track training programs and optimize technique and peak performance.”

The ViPerform can measure an athlete’s symmetry while running or working out, key to determining if a player is nursing a hidden injury.

“Elite athletes are great at compensating for injuries or soon-to-be injuries that they don’t even know are brewing,” Wildermuth said. “Particularly for running—are they favoring a leg? Is their ground contact time symmetrical? How about the stability of the knees? The human eye only operates at 30 frames per second. We collect data at 200 frames per second. We pick up stuff that you’re going to miss if you’re just watching athletes perform or even videotaping them.”

These devices are just a few interesting examples of the type of technologies which are available or soon to be. In their current forms, none are likely to spread through baseball like the radar gun did. However, these are the roots of a revolution. Cell phones would not have revolutionized the world if all they did was make calls. It is the combination of a number of separate technologies—a still camera, video camera, GPS, accelerometer, calendar, and internet connectivity—that made smartphones a worldwide phenomenon. Imagine a device that measures a pitcher’s throwing motion like the Motus mThrow, measures muscle fatigue like the BSX Insight, and sticks to the player’s uniform like the ViPerform. When that device exists—and it will—baseball will be forever changed.

“The goal of every wearable technology is to make the user forget they are wearing it,” Freckleton said. “The best way to do that is to embed the technology into a garment that they are already used to putting on. Without a doubt, that’s where the industry is going.”

Virtual Reality and Augmented Reality

Tony Gwynn famously traveled with his VCR on road trips to do video analysis. Since then, video scouting has evolved into DVDs and now tablets. The next generation will see it transcend video altogether. Virtual reality (VR) has already ridden the hype cycle wave, but computing power is finally good enough to enable the kind of realistic experiences we were promised when VR was first introduced more than a decade ago. The Oculus Rift and Samsung Gear VR are consumer-ready technologies, waiting for the next Tony Gwynn to bring VR to baseball.

From a personal perspective, I can attest that modern VR experiences are incredible. Although you are always aware of the headset, the VR truly tricks your brain. You lose yourself to the experience far deeper than any video or 3D movie. Taking off the headset is like stepping out of one reality and back into the real world. Don’t take my word for it, watch this guy fall all over himself because his brain is convinced it’s on a roller coaster.

Imagine this scenario. You are a major league player who will face a pitcher for the first time tomorrow. You head to the batting cage, the team’s VR assistant loads up the program, and you slide on the headset. From your perspective, you are now standing in the batter’s box, in the stadium full of fans, looking at tomorrow’s starting pitcher on the mound. He winds up and throws, and it looks exactly like it will during the game tomorrow. You can virtually face that pitcher dozens of times, seeing every pitch in his arsenal at the exact speed and break that he throws it. Could there be any better preparation other than actually facing the pitcher himself?

EON Sports is a VR company heading this direction in football. It has created a VR program for quarterbacks to practice reading defenses.

VR can be used in player evaluation as well. The Red Sox currently use a computer game in their amateur scouting process, in which players identify pitches on a screen. The logical next iteration of this process would be using a VR headset, putting the player in a more lifelike situation. Also, instead of needing to drag around a laptop and have a player sit at a desk to perform these tests, a scout will need only his smartphone and some cardboard.

Augmented reality (AR) is a similar-but-different technology, where the person wearing the device sees holographic overlays on his normal field of vision. The best known example of this is Google Glass, which was the butt of several jokes, but was a fairly impressive first stab at functional AR. A better example of the potential of AR is Microsoft’s Hololens.

AR will likely be an important field of technology for the future of the fan experience, but its usefulness for baseball players will be limited. A player wearing an AR headset could one day see real-time overlays with pitch speed, tendencies, or even messages from the manager. However, those benefits go beyond data collection and into game-altering functions, which is why AR is likely far away from being allowed on players during games by Major League Baseball.

Brain Measurement

“Measuring brain activity will get into mainstream sports,” said Michael Bentley, founder of Blast Motion. “We are able to measure the ball, and we’re starting to be able to measure the athlete, but [we need] to truly be able to measure the athletes from their energy systems. What can they do today? As they walk into the stadium, is their central nervous system ready to be stressed or is it time to rest?”

To this point, most of the new data streams discussed in this and part one involve tracking the athlete’s body. Measuring thought and mood is another frontier where technology will take us over the next generation. Bryan Cole wrote an excellent piece on brain measurement in baseball at our sister site TechGraphs.

While we are still in the early days of harnessing brain measurement, the technology is progressing and its cost is dropping. There are consumer products on the market, such as the Muse headband, and even toys, such as the Mattel Mindflex. Having tested these, I will say the scope of what is measured is narrow for now. These devices can sense whether you are concentrating hard, but they can’t tell the difference in what you are concentrating on. Still, functional brain sensing technology for a few hundred bucks is pretty wild.

This kind of technology could be embedded into hats and helmets in the near future. It might sound crazy now, but one day, players will already be used to wearable devices that track their movement and vital signs. The leap to brainwave tracking won’t seem nearly as big as it does today. Consider Tommy John surgery—putting a new ligament into an elbow. It would seem impossible to a player from the 1800s. Only because of gradual advances in the medical field does it feel normal to us today.

Health Technology is Baseball Technology

Health care is a relevant field for everyone on the planet with a pulse. In that context, sports are secondary, but both fields share a similar goal: keep people healthier for longer. In baseball, the future of health technology is critical because each player represents a multi-million dollar investment, the return on which is contingent on health. Preventing a single hamstring strain for a star player could be worth $5 or $10 million.

This field has a wide variety of interesting technology, more than can be listed here. What follows are simply a few selections, which exemplify what the future could hold for the future of baseball training staffs.

Athos is a good example of what a full-body analytics system could look like. Instead of focusing on one muscle or motion, the goal is to measure every movement of the body. It is probably too restricting for many players’ tastes now, but the technology will get smaller and easier to wear. Future iterations could track players during workouts and games, sending data about each muscle, looking for warning signs of a pending injury.

The Colorado Rockies are the first major league team to begin testing with Musclesound, a technology that uses ultrasound to measure glycogen levels, the “fuel” inside a muscle. Currently, this test is performed in the trainer’s room, but it is easy to extrapolate how this technology could be embedded into a wearable devices in the near future.

All these new data streams coming off wearable devices will require a central repository, which collects the data and makes them usable for the team’s staff. Kitman Labs is a good example of the kind of data management platform that will be vital for teams as technology becomes a bigger part of their day-to-day operations. Kitman, which has partnered with the Dodgers, currently relies on a combination of objective and self-reported data, but it is not hard to imagine how it could begin bringing in streams of data as more technologies are adopted. For more on Kitman Labs, check out this piece by Bryan Cole at TechGraphs.

While technology will help prevent injuries, they will always be a part of the game. One way to expedite recovery time is to have less invasive surgery. Robotic surgery, for example Da Vinci Surgery, could make for less invasive procedures, less trauma, and fewer human errors. The Da Vinci system can’t yet do a Tommy John procedure, but once it can, it will likely reduce the recovery time significantly.

The Future of the MLB Rulebook

Off-field technology will no doubt be adopted first, but baseball will soon have to confront its policies regarding on-field electronics. Devices that track a player during the game are harmless to the in-game competition. Some of the companies interviewed for this piece are already in discussion with MLB to rewrite the rulebook.

The biggest fear for MLB is communication during the game. Someone watching the game in the clubhouse could send a small vibration to a wristband or other wearable device alerting the batter when the catcher calls for a curve ball. Another issue will be devices that will enhance senses. A player wearing a contact lens that gives him better than 20/20 vision and a sign-stealing graphical overlay is the PED scandal of 2030. Of course, in this context, PED stands for performance enhancing devices. This technology is far away, but several companies already are working on AR contacts and enhanced vision.

Creating a list of approved, tracking-only devices is a good start, but a harmless wristband could be modified for nefarious purposes. There is no obvious solution to this issue, but a flat ban will not be an effective long-term plan. Players, broadcasters and teams will soon be clamoring to have more devices used in-game.

Looking further down the road, MLB may not have much of a choice. How do you catch players when devices are smaller than a postage stamp? How do you enforce a ban when the device is embedded in the player’s eye, brain or body? Baseball has a few years to figure it out, but it is time to start having these conversations.

Technology as the New Competitive Advantage

“There is going to be a generation of players that come up used to technology,” said Joe Nolan, CEO and founder of Motus Global. “I have three sons, and I see the way they are growing up compared to the way I grew up, and technology is a part of everything they do. It’s inevitable. Technology is going to become more and more involved in all sports. In the next 10 or 20 years, there are things we can’t even imagine that will probably become a part of baseball.”

So, 5,000 words later, I hope I have provided a look at the kinds of technologies that will be important to baseball in the future. In the last few words, I will try to prophesize the implications of this technology.

Starting soon, MLB’s new video technology, Statcast, will provide new data streams to every team, like PITCHf/x before it. Each team gets the exact same data, which means there is no competitive advantage in the data, only in who can use it better. The technology featured in these articles will not work that way. A team will begin using a piece of new tech, be it a swing tracker or an EEG headband, and it will own that stream of proprietary data. The new arms race in front offices will transition from “Who can build the best predictive model given the same dataset?” to “Who can come up with the best new streams of data?” In fact, this transition has already begun. Do you think the Dodgers are running a start-up accelerator to turn a profit?

All this falls within Bill James’ original definition of sabermetrics: “The search for objective knowledge about baseball.” This movement began with box score data. In the next few years, it will encapsulate more volume and variety of data than James probably dreamed. Nevertheless, his definition still holds the basic truth of why this new technology exists and how it will be used.

In my opinion, the effect of new technology will be felt first in amateur scouting. The draft is far from random, but the number of high picks who bust and superstars who come out of nowhere leads me to believe that baseball is nowhere near the peak of objective knowledge in this area. These new technologies are small, mobile and affordable, meaning more data will be collected on amateur players than ever before, by scouts and the players themselves. These data will shine a new light on an area of baseball that is currently dimmest. Better data will lead to better draft picks. I expect the first teams to harness the new wave of technology will have a similar advantage to the teams that first embraced sabermetrics.

A very interesting article Jesse. It will be fun to watch how these technologies develop.

How about enhanced contacts and a holographic strike zone for umpires? The biggest sellers though will be on those improved glasses advertised in the back of magazines that see through women’s clothing.

Excellent article. I have tried the VR roller coaster. My stomach was quezzy for the next half hour or so.

Re: Stealing signs. Wouldn’t technology be used to hide the signs? That is, instead of putting down fingers, the catcher sends an electronic signal by manipulating his glove hand or something.

Then the cheating would move to intercepting that signal.

If there were secret electronic signals, then wouldn’t they go from pitcher to catcher, or from coach to both? The only reason the catcher gives the signal now instead of the pitcher is because he can hide the signal.

I don’t think that’s the reason at all. I would say it’s because a pitcher has so much going on in terms of just trying to execute his pitches, that they want pitch calling to be handled by the catcher. Also, if it’s the catcher’s job then you can have standardization across your pitching staff, rather than each pitcher trying to call his own game.

I recall when they were talking about how VR sex would be just like the real thing. I’m an old fogey, I guess, but there seems something disturbing about the idea that we can create an artificial experience that is no different from reality. Why go to a ball game when you can just simulate one? Why play sports when you can get the same experience in cyberspace (or whatever you would call it)?