Roll With It: The Dice Baseball League

Who knew a pair of dice could make following baseball even more awesome than it already was. (via Sankar 1995)

On a hot teenage summer afternoon, a baseball game played out.

The pitcher stretched into a windup, flung the ball to the plate. The batter swung, cracking a liner right by the pitcher’s cap, trailing into center. Running out of the box, the batter rounded first and retreated, content with a single, fist-bumping the first-base coach.

And so Ross, my childhood best friend, and I looked up from the twin dice and notebook paper we’d used as scoresheets and celebrated the world we’d created: the Raleigh and Ross Dice Baseball League.

On the field, Ross’s older brother, Josh, played out another dreary, meaningless summer league baseball game. We watched as Josh took the sign and laid down a perfect squeeze bunt. “Sometimes,” Ross smiled at me, “you gotta roll the dice.”

***

The basics of the Raleigh and Ross Baseball League were dreamt up on the oppressive bleachers of Trevecca Nazarene University’s baseball field — a field on which I, merely four years later, would play one bench-bound season of collegiate baseball. In 2002, I was 15 and Ross was 13, and we were there to watch Ross’s ambitious older brother Josh play for his travel team. (The opposing pitcher that day? Nashville’s own David Price). But summer league baseball games — even those pitched by future Cy Young winners — are for scouts and sunscreen-slathered moms, throned in their visors and folding chairs. We were bored, and Ross’s mom must have had dice in her purse. (There’s no data for the probability of this event, but it seems, in hindsight, unlikely.) We also scavenged it for pen and paper.

Baseball is a basic game — throw, hit, catch, run — and beautiful because of it, its grassy outfield expanses leaving room for deep sabermetric dives and back-of-the-baseball-card numbers alike. Talking through the basics, we jotted notes with his mom’s blue pen, our handwriting smudged and distinct. We passed the dice between our hands: baseball’s infinite possibilities at our fingertips, clattering on the aluminum bleachers.

***

Ross grew up a bike ride away. We spent our summers cultivating happiness and comfort at every turn. Our fathers were athletes, hard workers, and great bemoaners of laziness. Even now, into my thirties, if any couch-lounging lasts longer than one 20-minute television episode, I hear my father’s voice prodding me from my idleness, urging me to go out and do something.

Despite our shared fatherly antagonization, Ross and I were fervently committed to our own relaxation. We did not take kindly to Ross’s older brother Josh. We felt his plyometric training, weight-clanging full-body workouts, and taking a summer job at 15 in efforts to purchase a car reflected poorly on our lack of drive. Josh would come over to the house to talk to my dad about working out; Ross and I would slink downstairs to the PlayStation.

Ross was always down. It is what I remember most about our teenage summers: the energy we snowballed towards one another, neither of us ever turning down an experience, a journey to the next neighborhood over on our bikes, another run of Triple Play, another roll of the dice. We fed off each other’s energy. Sleep would postpone itself until sunrise if we had Friends to watch. We were perfect partners in what our fathers would have called the unforgivable crime of our own sloth.

Without any somebodies to become, we had all that humid and empty space in which to dream, to create, to conjure up worlds — or, in this case, take one that already existed and make it our own.

***

We were not good at math.

We used two dice and consulted no theorems or charts, Moneyball or bell curves. We just rolled with it.

The game was rudimentary and fast; we might have been accused of injecting the dice. Pitchers stood absolutely no chance. Ross and I played 110 games of dice baseball (the Raleigh and Ross Dice Baseball League’s colloquial title) that summer, and not a single game went by without the sound of our whispered home run commentary, “It’s back, to the wall, it’s outta here!” Most games featured a half-dozen homers. If this sounds like early-2000s baseball — and shit-loads of fun — it’s because it was.

Using player attributes from EA Sports’ Triple Play 2002 as a reference, we created personalized “hitting charts” for over 100 players. We took two dice and their 11 possible outcomes (2-12) and created a reliable baseline to determine baseball’s vast array of offensive possibilities. For a player like, say, Jeff Bagwell, a dice roll yielding a two or three cranked one out of the park. Anything between four and six swung and missed. Seven, eight, or nine was a good old-fashioned out. Integers 10 and above were base hits.

You can see, then, how home runs might be easy to come by. For Bagwell and the 37 others with that home run probability (noted as “HR (2-3)”), every pitch had an 18% chance of being a hypothetical souvenir. Every pitch! This is how major league baseball was at the time, and we certainly weren’t complaining. You couldn’t test a die for HGH, and why would you want to?

***

|

***

Dice baseball teams were drafted via snake draft, without pomp or handshake from the commissioners, in my basement. Players were divvied based on a kind of randomness that I can neither remember nor find evidence of a method to. We unnecessarily filled out eight 25-man rosters, naming the teams based on which real-life major league team had the most representatives. The Expos (still a thing!) featured Vladimir Guerrero, Jose Vidro, Javier Vazquez, and Bartolo Colon. Lining up for the Phillies were real-life Phils like Scott Rolen, Marlon Anderson, and the immortal Brandon Duckworth. Lineups were then created, stacked ones that saw Bagwell batting seventh for the loaded Phillies, and a young Albert Pujols hitting seventh for the badass Giants.

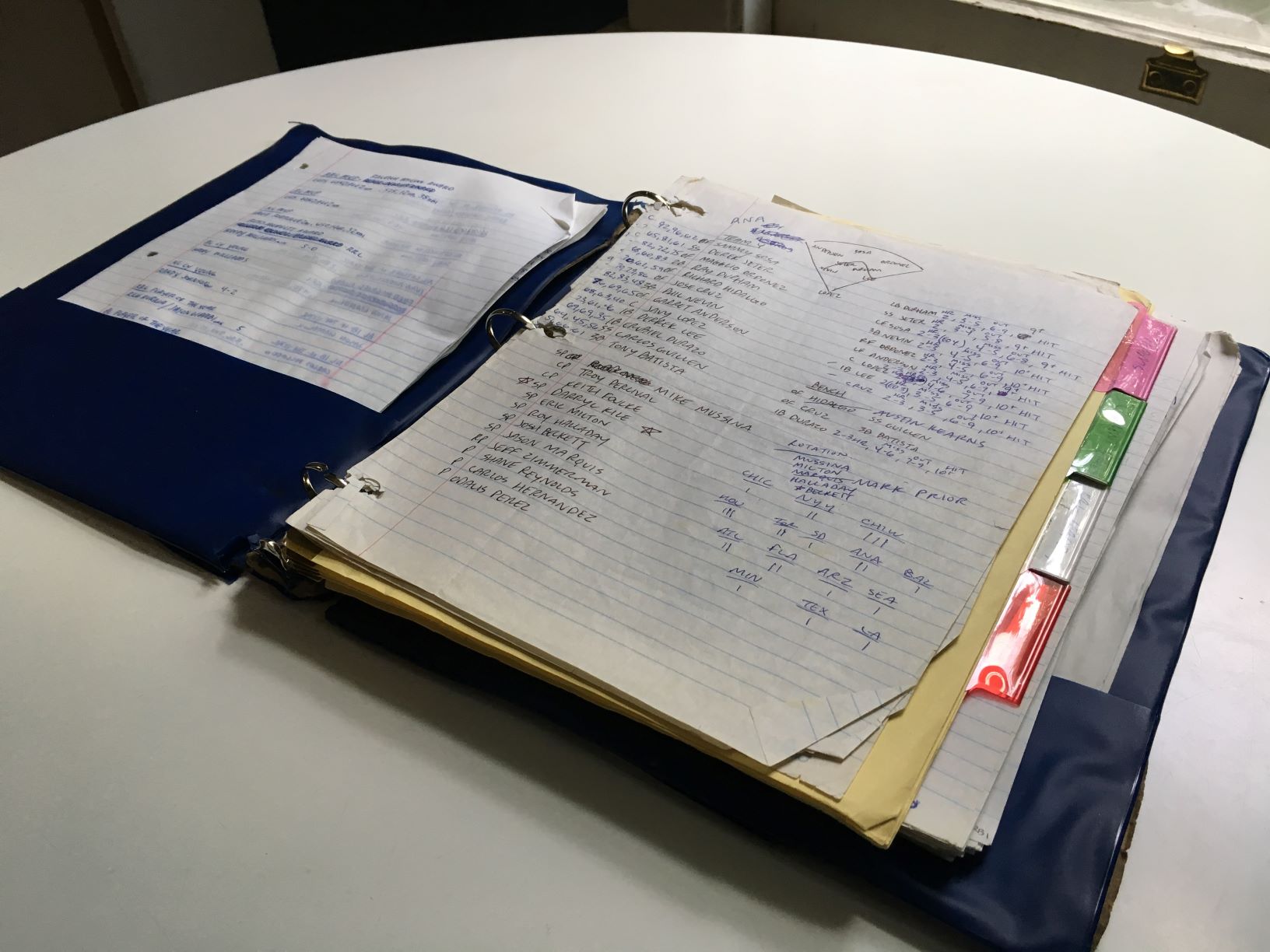

I still have these rosters — I still have everything — in a scraggly blue binder. We played, it seems, just enough dice baseball to fill the notebook but not enough to compromise its three-ringed integrity, as it has protected these scoresheets for over half my life. The binder itself has tabbed sections, as I’d evidently showed more commitment to dice baseball organization than to any schoolwork, my homework haphazardly shoved into textbooks. Not only were scoresheets annotated and filed by date, but there is a landing spot for team rosters with attributes and lineups and separate sections for standings, team-by-team stats, and weekly-refreshed league leaders.

The RRL leaderboard through 24 games.

The scorecards are immaculate, hand-drawn, and customized for each game, occupying a major swath of the RRL notebook. Each of the 110 dice baseball games was recorded on college-ruled paper, featuring both teams’ lineups in parallel vertical columns, below which was a horizontal line score. As the game unfolded, a “live box score” kept a tally in the columns, and at the end of the game, the bottom portion of the paper was used for bookkeeping: pitchers of record, home runs, player of the game, and any sort of game notes.

The scorecard for a game between the Cardinals and the Twins, noted as “*Classic game — arguably best game ever.”

Ross and I shared rolling duties. We’d switch off inning by inning, swapping the dice for the pen. It was rare to let someone play a whole game by themselves. To let someone else play a game without you felt like missing your child taking first steps — what might baby Kenny Lofton do? You could always catch the box score after the game, but despite our starred annotations — *Classic game!* — there were no highlights.

Although Ross and I shared playing, cheerleading, and broadcasting duties, I kept the books. The folder lived at my house, and I computed the league leaders by hand each week. My handwriting — all caps, neat, slightly pitched to the right, and almost exactly the same as it is today — is on everything.

***

The inaugural game, as indicated by the signatures of the co-commissioners, between the Expos and Phillies, took place the very afternoon of Ross’ brother vs. David Price. We got home, the rules sketched out, the rosters taking shape, and took the field. The dice gods smiled upon Marcus Giles, who slapped the first hit, a single. One of Ross’s hanging dice throws resulted in the first RRL home run by Troy Glaus. In hindsight, the opening game was quite off brand for the league, dominated by good real-life pitchers Randy Johnson (8 IP, 5 H, 2 ER, K) and Roger Clemens (8 IP, 5 H, ER, 3 K). The Expos won it, 2-1.

Documentation of the RRL’s Inaugural Game, complete with the signatures of the co-commissioners.

We played out the rest of the opening three-game set before dinner. The second game, a simple 3-0 Philly win (with even fewer hits — five apiece for each team), was the final one to sidle even remotely close to the actual laws of life and baseball and humanity. The third and final game, still being played on those Ross’s-mom-salvaged paper scraps, really got the ball — er, dice — rolling. Jason Kendall (!) hit two homers, and the Expos scored four runs in the bottom of the ninth to walk off with a win.

***

Before any hitting action could occur, we had to roll the pitch. 2-5 was a ball, 6 and up was a strike. Throw a strike, of course, and the batters come into play.

It speaks to the brand of baseball we grew up with that we did not offer the slightest advantage to pitchers. At-bats started with a 1-1 count, but this only vaguely offered the chance at more pitcher strikeouts, and was mostly so Ross and I could speed through an entire corridor of games in an afternoon. Without any attributes of their own to offer, all pitchers were uniform, meaning Randy Johnson and Randy Wolf were… exactly the same. It seems rather silly now — we’d have to totally redesign the dice to account for Max Scherzer — but back then, it just made sense. Who wanted to roll the dice and watch their made-up players slump back to the dugout after a K? Yet despite the homogeneity of pitchers, Ross and I were committed to reality. We’d pull a pitcher if he was getting shelled (except sometimes, curiously, we didn’t — heed this disastrous Andy Pettitte start: CG, 13 runs, 19 hits, 6 walks, zero strikeouts), and would always bring in the unnecessary closer to get unnecessary saves.

The games themselves were crazy. In one extra-inning affair, Nomar Garciaparra — an interesting case, as he possessed the unusual home run equation of HR (2, every other 3), which required separate dictation and a keen player’s eye — went 7-for-8 with four singles, a double, and two home runs. In that same game, Chipper Jones went yard three times for seven RBI. Rich Aurilia, a player you’re just now remembering and who was actually quite good in both real baseball and RRL baseball, once hit a two-run homer to tie a game in the sixth, a three-run homer to tie it in the eighth, and a game-winning solo shot in the 10th. That is some Little League/Triple Play home-run-derby-in-the-living-room shit.

A playoff game — oh yes, there were playoff games — featured 11 round-trippers. One late-season contest made it 26 outs without a home run. It would have been the first game to finish without a homer in RRL history — and then Alex Rodriguez hit a walk-off, three-run blast.

Ross and I celebrated these moments like we were the proud dads of the players, leaning against the fence, sneaking dips of Skoal. We had made something with real stakes, real drama — and not only were we celebrating walk-offs and wins, we were cheering that we made this possible. We had created this.

***

Our most ambitious project was personalizing the batting chances for each player — from Barry Bonds (the nearly-insane “HR [2, 3, and every other 4]”) to Ben Davis (“HR [sorry, no]”).

The most accurate depiction of baseball was when Ross and I assigned players the combination of “HR (2-3)” and “HIT (10+)”. Using this baseline, Magglio Ordonez hit a modest .275, with nine homers and 19 RBIs in 27 games. Phil Nevin slugged five home runs, drove in 19, and batted .241 with those same attributes. Andruw Jones went .308/7/20, while Brian Giles rode those numbers to .296/9/25.

The “HR (2-3)/HIT (9+)” guys are where it got crazy. Those guys broke the dice. Jason Giambi went .470/16/40. In the heart of the Twins’ league-leading offense (182 runs in 27 games!) were Helton, Chipper, and Nomar. Helton, the “worst” of the three, hit a paltry .436/9/34. Garciaparra, at the height of his real-life Nomah powers, picked up Helton’s slack and hit .432 with 17 bombs and 32 RBIs. Chipper Jones hammered every dice roll in sight: .456, 17 home runs, 37 RBIs. If God had invented a dice baseball game and drafted Himself onto the Twins, He wouldn’t have hit .456 with 17 jacks.

Luis Gonzalez, after his frighteningly good IRL season, went and added two hundred points to his batting average in his MVP RRL season: .525/12/38. Ross and I, having heard of Brad Pitt but not Billy Beane, can be validly critiqued for our batting average obsession. But I will come to my own teenage defense and say that when you roll two little dice together thousands of times over the course of a humid summer in your basement, and the imaginary avatar of Luis Gonzalez — legs spread like a samurai, facing the pitcher like he was some charging bear — gets a hit 52% of the time? His WAR — wait a second let me check this, our handwritten notations are hard to calculate oh wait here it is HIS WAR WAS FIVE THOUSAND. You could not stop Luis Gonzalez in dice baseball. You could only pray to the dice baseball gods for mercy.

In addition to Bonds, we gave Manny Ramirez, A-Rod, and Sammy Sosa the bombs-away every-other-four home run designation. These guys, predictably, wore out the dice until Ross had to ransack the family Yahtzee! box for more. Sosa thwacked .475 with a cool 20 dingers and 37 RBI. Manny being Manny in the Raleigh and Ross League meant far fewer baserunning boners and way more bombs, as he swatted .434 on the brief season, hitting 16 out of the park and driving in 29 teammates. A-Rod strolled calmly through a .450/14/32 season. Barry Bonds hit .391, which isn’t that much better than the actual .370 he hit that year, with 18 homers and 30 RBI. He only walked once — and was never intentionally walked, which, along with bunting, praise be to Bill James, never happened in an RRL game. (Curiously, several instances of hit-by-pitches occurred, although for the life of me I cannot determine what sequence of dice integers could have spurred a hit batsman. Was revenge spun into the dice?)

It is, I suppose, a little odd that we didn’t account for pitching. Ross went on to pitch in college, after all. Perhaps our future descendants will unite and create an addendum to the game, like Tolkien’s kids, extending the universe on down the generations. Our sons will have grown up without a version of Baseball Tonight that ends its show with “Going, Going, Gone!” and a full recap of who all hit home runs around major league baseball that evening. They’ll have replaced it with something like “K Korner,” and it’ll just be Karl Ravech’s dead eyes narrating a list of who all struck out that night.

The fastball flingers will be their gods. Thor, Sale, Snell, deGrom: These will be our children’s heroes. Will it be sad? Yes. Will our children make horrifically boring baseball dice games? Yes. Will their imagination and childlike wonder ever be captivated by something as disgustingly pure as the great home run chase of 1998? Will they ever feel a tinge of boyhood eroticism watching a superhero like Brady Anderson hit 50 bombs in one summer? Will they even know the look of a man who we’re all just going to pretend isn’t on steroids?

I lament for my unborn children.

***

For a couple of guys who could not have been less interested in making their dads proud on any actual baseball diamonds, Ross and I played a lot of forms of baseball.

We whacked a light foam ball with an old tennis racket, playing a doll-sized version of baseball in my basement. The pitcher, standing ten feet away, could throw it as hard as he possibly could and with as much juju as he could muster, the ball dancing like a dragonfly stuck in a balloon. The close distance made up for the fact that you were hitting a softball-sized foam ball with a tennis racket. Home runs were anything above my bedroom doorknob. It was a frenetic game — you could run around the bases in about seven twelve-year-old steps.

Tennisball-baseball — which is somehow what we called it, five syllables and all — happened in my yard or his, and bare feet were required. Our games initially called for us to lob the ball in, but when we started outgrowing our yards we amped up the pitches. But even that could not hold us back, so adept had Ross and I become at mimicking the looping lefty home run swings of our favorite players: Fred McGriff and Ryan Klesko, respectively. Our heroes weren’t the most beloved players of the ’90s Braves, but McGriff’s blase approach and Klesko’s zero-f’s facial grooming made them perfect for us, barefoot and sweaty with better things we ought to be doing.

Things like training for our actual baseball games, for we, of course, had our summer league season to play. Both of us played for competitive travel teams, traversing the mid-state on summer afternoons when our friends were at the wave pool — or better yet, shirtless, on the couch, playing video games.

We played a lot of those, too. For the better part of three summers, Ross and I would bike to each other’s houses and play Triple Play. We’d play that ridiculous home run derby in the game’s variety of off-kilter locales — in an oversized living room, at a construction site, wherever. The rosters were also customizable, so we would draft our ideal teams and play epic seven-game series against one another.

One day, we had real baseball to play together. My senior year of high school, Ross was a sophomore pitcher. I started in left field, and Ross was an up-and-coming starter. He pitched a complete-game shutout in the state tournament, and some reckless high roller must have got hold of my dice that day, as I drove in four runs, taking our team to within one game of the tournament final.

***

If you had asked our friends, that summer should have been the one when we hung out at house parties or tried to see which set of cool parents would buy us beer. But Ross and I weren’t really interested. It could have been our commitment to church youth group or the fact neither of us could drive — but really, we had our bikes, our dice, and each other. We couldn’t have known then, but we had used our last little bit of childhood whimsy at just the right time, the last best summer. I made varsity that year, hoops and baseball, and got my first girlfriend. She had a car, and she steered me to all kinds of new places. The dice went on strike, tucking themselves away in the front pocket of the binder.

Ross and I built ourselves a history, and when the rest of our life finally came, the girlfriends and the cars and the college scouts, we forgot about what we’d built. And what Field of Dreams didn’t tell you is that if you build it, you’ll forget about it, and it will fall down, and it won’t really matter if they came or not in the first place.

***

It’s 2019. Ross lives down the street, still just a bike ride away. He’s got a house, lives there with his wife and daughter. He’s got another house, too, the one I live in — he’s my landlord. Tucked away in the corner of the walk-in closet in the house Ross owns is a blue binder, a pair of dice tucked into the front pocket.

The binder.

The season has outlasted our childhoods, our baseball careers, and, if we don’t roll the final few games soon, may be rolled under the tarp of our futures. It’s tough to roll the dice when you have a family to feed, work to do, a dad to be. His daughter is beautiful, eager and giggly — she seems already willing, ready, ready for it all. Ross loves her; I like her chances.

A few years ago, digging through my closet, I came across the old RRL binder, picked up the dice and played a few games. I was obviously in a hurry, not really bothering to notate properly — there are no final pitcher’s stats, the live box score hustled and scrawled. I made it a few games further into the playoffs: Game Six of the ALCS awaits.

I want to play now, to take an hour or two, roll the old dice around, see if my fingers still remember the rhythms of the line score, the numbers and figures and fast math that turns a double into a triple, the kids’ creativity that makes a routine groundout into a diving play at short, a spectacular throw from the knees, a bang-bang play at first.

I probably should give Ross a call, see if he wants in on the action. I wonder if he’ll remember what it was like in that summer, back when our dads wanted us to do something that mattered so we did the only thing that did. I wonder if he’ll remember the names: Paul Lo Duca, Sean Casey, Mike Lieberthal, Juan Gonzalez. I wonder if they’ll remember us.

It’s not about if you win or lose, and it’s not really about how you play the game. It’s about doing something that, in your mind, in your three-ring binder, on your parents’ coffee table or wherever can sustain a thousand dice rolls — it’s about doing something that lasts forever.

And so the season rolls on, never to end.

Does Raleigh McCool sound like the name of an anti-drug skateboarding cartoon dog shown during 80s Saturday morning cartoons?

Does Raleigh McCool sound like the name Seth Rogen considered before settling on McLovin?

Does Raleigh McCool sound like the name your 8 year old gives himself?

This is the best thing I’ve read written by someone with a pseudonym since the letters of Mrs. Silence Dogood.

(pssst, McCool is an actual last name, derived from “Mac giolla Chomhghaill meaning ‘The son of the follower of St. Comhghall’, a saint of 7th century origins” per the surname database)

In all seriousness this is a great piece of writing.

Love this. I “invented” a similar game at a similar age, where the dice determined the outcome of the at-bat. If memory serves, it was something like this:

2 – Triple

3 – Error

4 – Walk

5 – Groundout

6 – Strikeout

7 – Single

8- Groundout

9 – Strikeout

10 – Flyout

11 – Home Run

12 – Double

Would not stand up to Sabermetric scrutiny, to be sure.

Really enjoyed this, and brought up memories of games we’d invent and abandon on what seems in my memory something like a daily basis. I think one was played with real baseball cards and a chutes and ladders spinner.

Great stuff. Reminds me of a couple seasons my brother and I played drafting teams with MLB Showdown cards, he kept the stats on pen and paper and we would put them all into an Excel spreadsheet after a few series. There were some unexpected greats like John Jaha and CJ Nitkowski, a surprisingly disappointing ARod, and a Dodgers squad fronted by dual aces Kerry Wood and Curt Shilling (and the top slugger Jeff Bagwell and fan favorite utility Sean Burroughs) coming up short in both World Series.

I played the crap out of the 1964 edition of Cadaco All-Star Baseball and have dozens of notebooks (binders in other parts of the country) filled with my scorekeeping over the past five decades. With 60 discs, I could make six 10-man teams, with names like the Coke Cubs, Pepsi Pirates and A&W Astros. I played it every afternoon after school by myself, doing my own play-by-play. Since then, I’ve found an online disc maker and have amused myself in retirement. Those notebooks are in my “this goes in case of fire” box. The wedding pictures? That’s for my wife to decide.

Good to know I’m not the only one who did this, but with baseball cards as the reference point.

I’m actually working on a baseball dice game right now. However, mine combines rolling a 20-sided die with a normal 6-sided die. First you roll the 20-sided one, and you get a home run with 20, a double on 19, singles for 16-18, etc. Then the 6-sided die is rolled for variations on most of them with possibly a second 6-sided throw for possible baserunning and defensive decisions on some of the plays.

For example, if you roll a 19 (double) and then a 5 or a 6, you have the option to try for a triple with another roll with different probabilities of being thrown out. A 1, 2, or 3 is a strikeout, but if you roll a 3 followed by a 6, you reach (and all baserunners advance) on the third strike rule (as long as there are 2 outs or 1st base is unoccupied).

Whenever there are runners on base, more dice rolls occur before the normal rolls while giving you strategic options like stealing and bunting, or you may benefit from a balk or wild pitch or get picked off.

Then you have the option of using alternate defensive alignments (including an infield overshift) that adjust certain probabilities…

You can also just play the simple version, which cuts out all the strategic decision making if you prefer.

This was a great piece of writing, even quite moving. It reminds me of The Universal Baseball Association by Robert Coover.