The Living, Historical Illustrations of Tim Godden

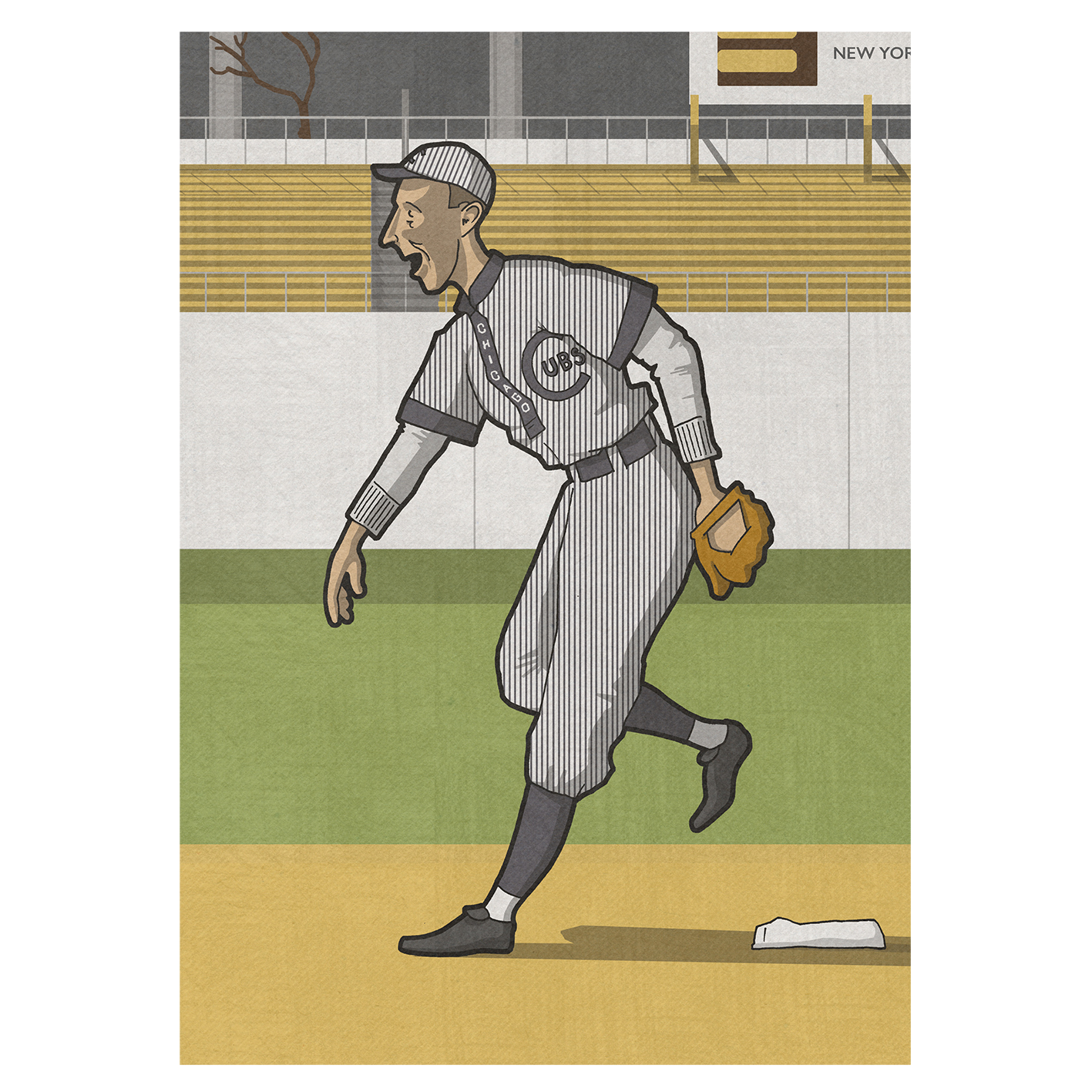

Tim Godden’s illustrations give a different look to today’s game of baseball.

Tim Godden needed a model, but as a Red Sox fan, he refused to draw a Yankee. Instead, he settled for Mel Ott.

Godden liked the 1939 World’s Fair Patch, which was worn during the 1938 baseball season by all the New York teams. “That’s a really awesome patch,” he thought, the creative side of his brain kicking in. “But I can’t just draw the patch. That’s a bit silly.” And so Godden dove down the historical rabbit hole of the 1939 World’s Fair Patch and Mel Ott.

In the final illustration, Ott stands in profile with his bat over his shoulder having just finished his swing. He’s bounded by a thick stroke line, his complexity built by subtle changes in hue. On his left sleeve, front and center, is the patch — and then there’s the patch again, blown-up to the same size of the superimposed Ott. The illustration embodies both Godden’s style and his process.

“It’s fun to go off and do the research and not so much bring it to life, because it’s still very much alive, but to put my own voice into that reimagining,” Godden says. “I like the little nuances. And baseball is littered with them, isn’t it?”

Even though baseball illustrations make up much of the English illustrator’s catalogue now, Godden didn’t begin drawing baseballers until around three years ago. Before that, he wasn’t even a full-time illustrator. But in that short period, Godden has captured the imagination of many baseball Twitter users through his novel brand of illustrating both World War-era and current baseball players re-imagined during the early 20th century. And much like Mel Ott was a conduit for Godden to illustrate a patch, baseball is a conduit for Godden to pursue his two lifelong passions: art and historical research.

To take a step back: When Godden started working on illustrations consistently, it was a way to decompress from his daytime work: studying for a doctorate in cemeteries. Godden holds a Ph.D. in Architectural History from the University of Kent, having studied World War I-era French and Belgian cemeteries specifically.

What that field of study entails, in the most figurative sense, is a routine dalliance with ghosts. Soldiers, often just boys, sent off to war, never to return home. While fascinating, it’s not exactly the most uplifting work. So when he got home at night, he relieved stress by turning to a childhood passion of his: illustration.

At first, Godden drew the soldiers he was researching. In one illustration, a member of the Graves Registration Unit jots down the location of a grave. In another, a young soldier in the Wildcats, the 161st Infantry Brigade, 81st Division, holds a black and white cat aloft. Godden set up a blog to showcase his work, which got a fair bit of notoriety and led to commissions for more illustrations.

But after a couple of years of soldiers and World War-era work, Godden wanted to expand. He was looking for a niche that still scratched his itch for historical research but could also provide enough breadth to sustain his interest and his income. He gravitated to sports.

As a kid in rural Norfolk, part of the United Kingdom, Godden loved sports. He grew up with three brothers, all of them playing football (soccer) but also baseball and roller hockey. “Because there were four of us, we could decide to get into a sport and there were already enough of us to do it,” Godden said. Playing helped, but being a baseball fan in the UK in the ’90s was no easy task. Godden watched the one game a week on Channel 5, nominally a Red Sox fan because he owned a hat.

Maybe more importantly for the already historically inclined young Godden, Field of Dreams came out around that time. “When you see Field of Dreams and you see those guys coming out of the corn, I don’t know; it’s something that just resonated with me,” Godden says. “I guess for most historians that’s what they’re trying to do. They’re trying to reach out and touch history the whole time. And in that scenario, history is coming out to touch you.”

Godden found his new niche. He started sketching footballers and baseball players, some from the World War I era who had fought as well as played, and some from the current era re-imagined as they would have looked during the early 20th century. When Godden finished his doctorate, he started illustrating full-time, making his income off of commissions and sales through his blog.

While going full-time allowed Godden to finally realize his childhood dream of drawing for a living, it also allowed him to hone his style. “I’m drawing every single day,” Godden says. “You find your voice, you find that visual language that you’re looking for when you’re practicing that visual language every day.”

Even though Godden didn’t find consistency with his style until recently, he says that elements of it have been there since he was a kid. He traces the thick, black strokes that border all of his characters back to his dad’s Francophilia and the subsequent holidays spent in the Tintin-inundated country. His predilection for recreating people in profile also draws some inspiration from Tintin, as Godden prefers subjects that have simple, recognizable silhouettes. “Sometimes I’ll see a face, I’ll have no idea who the player is, but I’ll think, ‘I have to draw that guy. He has the perfect silhouette,’” Godden says.

In art school at the Norwich School of Art and Design, teachers tried to hammer the simplistic representative inclinations out of Godden in favor of more realistic depictions. “Why do you do that?” they would ask about his bold, black borders. “It doesn’t make it look real when you do that.” At the same time, though, Godden was learning about German painters Max Beckmann and Otto Dix, renowned artists who painted in a similar representative style and who proved to Godden that it was acceptable to create that way.

Now, Godden calls his style “graphic interpretation.” It’s not supposed to portray a mirror image of his subject, just a loose idea of them. “When I’m drawing it, I’m not trying to make you think that is Mel Ott because it’s clearly not,” Godden says. “It’s a couple of lines that give you the impression of Mel Ott.”

For inspiration, Godden will take a photograph of a historical event or some other shred of primary documentation like the patch and try to imagine it from a different angle. “Okay, what would this look like from that seat out there instead of this current perspective?” he asks. For instance, what would Willie Mays’ “The Catch” look like from the left field grandstand and not the conventional home plate view most baseball fans know?

“The thing that fascinates me about baseball is the history. I love that pull-through of statistics. You’ll be sitting watching a game and they’ll say something’s happened and the last time that’s happened was decades ago,” Godden says. “It’s that immediacy of history in the sport that lends itself to an illustration topic.”

When he started illustrating baseball players, much of that history eluded Godden. After all, he had grown up with only one TV game a week in the infancy of the Internet, before FanGraphs or Baseball-Reference or Wikipedia. As a historian, though, that lack of knowledge wasn’t demoralizing as much as enthralling. Godden loves searching for information that people haven’t found before and admits that if a project doesn’t require research, he doesn’t get much enjoyment out of it.

During his research, Godden would find someone he thought was a particularly obscure baseball player, thinking “Oh, nobody will know him.” Godden would draw him and put up the work only to find out his unknown baseballer was actually Rogers Hornsby. “That’s the daunting thing about being someone who’s learning the history and working with it at the same time,” Godden says. “That feeling of not wanting to get it wrong because there’s always someone that knows the answer.”

Godden is more familiar with the baseball landscape these days. He watches a good deal more baseball than he did as a kid, often working from 9 p.m. to 3 or 4 a.m. while watching that day’s games. With a 14-month-old son whom he takes care of while his fiance is at work, Godden’s days are split between the demands of art and childcare: “If I’m not drawing baseball, watching baseball or talking about baseball, I’m changing a nappy, giving him a bottle, and generally stopping him from chopping his fingers off in the door.”

And while Godden grew up without the Internet’s baseball resources, now he can do research with just a few clicks that would have previously necessitated a trip to Cooperstown. Social media helps in terms of inspiration, from baseball Twitter to the varied artifact and design collectors he follows on Instagram.

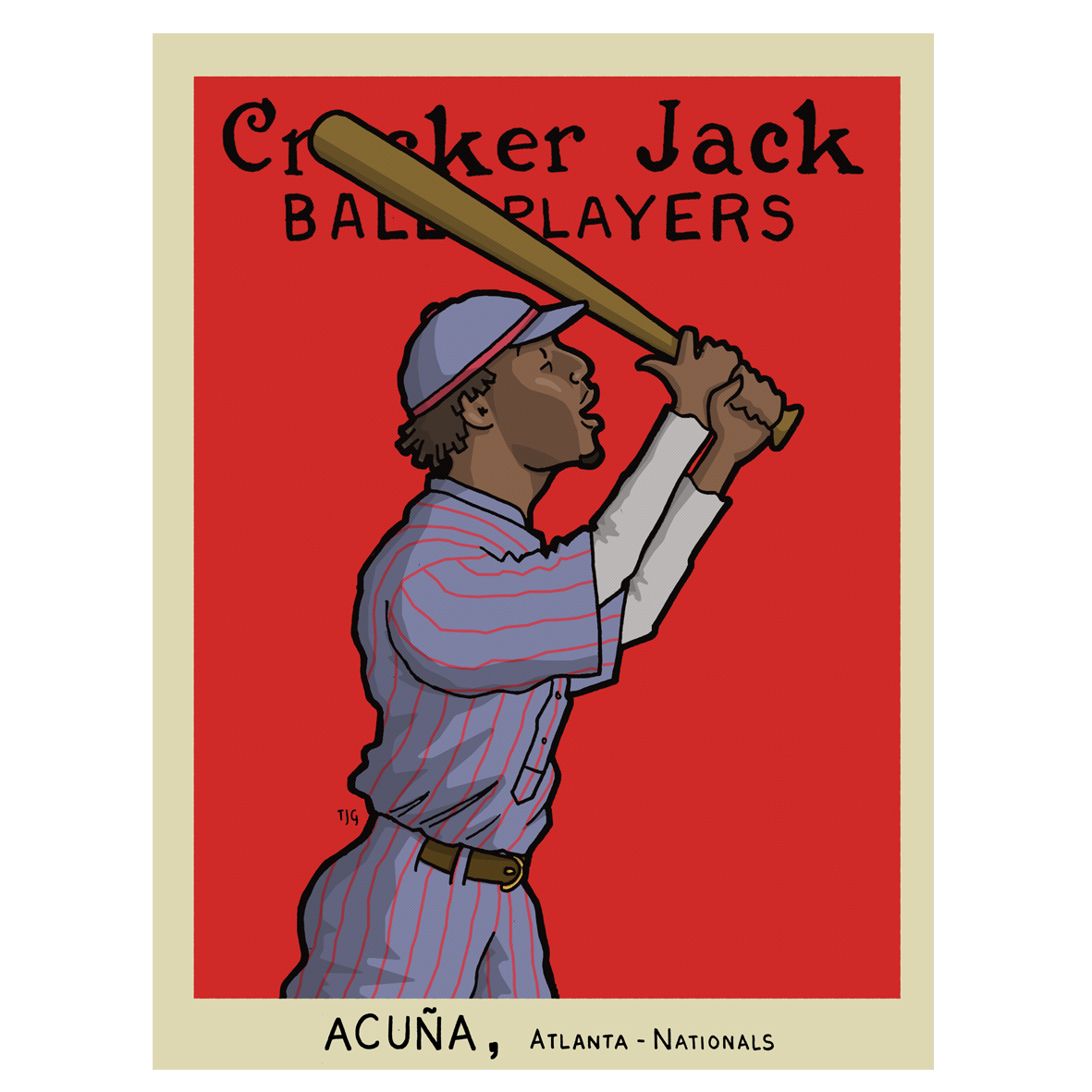

A recent project of his, the Cracker Jack card set, originated with his desire to create baseball cards but was inspired by seeing on Twitter the recent run of teams wearing throwback uniforms. “Even though they have a throwback uniform on, they don’t necessarily wear it how that uniform would have been originally worn,” Godden says. “So that gets me thinking, what would it look like if they actually wore the uniforms how they were meant to be worn? That’s where the Cracker Jack idea came from.”

Without realizing it, Godden created a bit of social commentary. By portraying current players as if they were in 1915, Godden made small compromises like giving Bryce Harper a beard when he wouldn’t be allowed to wear one and large compromises like portraying Vladimir Guerrero Jr. at all, even though players of color would not have been allowed onto the field.

The cards are a subtle bit of revisionist history, reminding baseball fans of the game’s segregated history while celebrating the accomplishments of players today. Ever the Red Sox fan, Godden has also put David Ortiz in the 1934 Red Sox jerseys and Mookie Betts in his own 1915 Cracker Jack painting.

One African-American baseball pioneer has always eluded Godden’s pen, though. No matter how many times Godden sits down to draw him, the illustrator just can’t seem to capture Jackie Robinson’s likeness. “I’ve probably sat and I’ve tried to draw Jackie Robinson 20 times, and they’re not awful but I’m still not happy with them,” Godden says. He can do both Bambinos — Babe Ruth and Josh Gibson — with no problem, but struggles with Jackie.

For the moment, though, Godden’s Jackie woes can be on the backburner. He recently created an infographic ahead of the Women’s World Cup for the National Football Museum and is in the early stages of a project commemorating the centennial of the 1919 Reds-White Sox World Series. Between those commissions, his own projects, and the 14-month-old, Godden stays busy.

And in the odd moments when neither baseball nor the child requires his attention and he needs to decompress, he plays guitar or takes walks through the national park next to where he lives in North Devon. He doesn’t plan to make a career of either.

Good read. Especially the cemeteries. I walk through old graveyards a lot. If you pay attention and have an eye for detail, you can learn a lot about the era in which these people lived and the social/economic strata they occupied. Too bad we do not have laws about preserving old ball parks the way we do with cemeteries. You could spend countless hours and days pedantically researching every speck of tobacco juice on the wall and odor of state beer in the bleachers.

Nice piece. When you say he draws “footballers” do you actually mean soccer players (US parlance)?

Great article. Godden comes across as an interesting and down to earth guy. I love his approach and perspective on baseball’s history