The Case for Eliminating the DH

Yesterday, a visual case for adding the designated hitter to the National League was laid out. Don’t listen to anything that guy writes. Anyone who really understands baseball knows we should eliminate the DH entirely.

The crux of yesterday’s case was that pitchers can’t hit at an acceptable level, creating a subset of major league at-bats that do not resemble the usual competitive balance between pitcher and batter. Further, it often distorts the at-bat for the batter who immediately precedes the pitcher in the lineup. Today, we’ll take a look at the underlying fallacies of said argument, as well as present several other arguments prosecuting the case against the DH.

The Fallacy that Pitchers Can’t Hit

That pitchers, as a group, don’t hit very well cannot be disputed. That they can’t is a completely different issue. Pitchers are not ordinary human beings, nor are they lacking in two core skills required to hit major league pitching, specifically, having elite arm-hand speed combined with elite eye-hand coordination.

A player who can throw a ball 90+ mph with enough coordination and accuracy to get it into small target 60 feet away has the requisite physical tools to hit major league pitching. What is missing is not the physical ability to hit major league pitching. Rather it is the training, desire and social conditioning that are preventing pitchers from becoming useful hitters at the major league level.

In many ways, the existence of of the DH provides a market disincentive to invest in a pitcher’s ability to hit, since for half of the major leagues, this value is non-existent. Thus, even if a pitcher is being groomed by a National League team, the element of the prospect pitcher’s value that is determined by his trade value dictates there is little value in developing his hitting.

This goes further than just a value statement, or a risk/reward decision made by senior personnel. It speaks to social conditioning with respect to the pitcher position, specifically that it is okay for a pitcher to provide negative offensive value so long as he can pitch.

If the DH were to be eliminated, teams could create a significant competitive advantage by investing in developing their pitchers’ collective ability to hit, creating surplus runs with pitchers who out-hit their counterparts by a consistent margin. The DH rule makes this more difficult, since pitchers move around and often lack the basic wherewithal to compete as a hitter.

Further, the societal expectation that pitchers don’t need to be good hitters percolates throughout the baseball development system, all the way down to Little League, where, if you are a great pitcher, little emphasis is placed on being a great hitter. Were this to change, I would suggest that pitchers over time would fit more naturally on the defense-offense trade-off curve, representing a drop off from the second base/shortstop hitting level that is closer to the gap between middle infielders and third basemen/right fielders.

The Reductio Ad Absurdum Argument, a.k.a. “Turtles all the Way Down”

If we accept the premise that pitchers shouldn’t hit because they don’t hit very well, we are essentially making the argument that when a position’s ability to hit is significantly worse than average, we should replace that position with a designated hitter. If we follow this logic, we would then see merit in allowing teams to have a pure defensive shortstop who would have his own designated hitter so he can focus on being an optimal defensive player (lighter, quicker, more agile, etc.) without having to worry about adding things that might offset his defensive ability (extra weight/muscle, time wasted working on hitting instead of a pure focus on defense).

This approach then could apply all the way down the defensive spectrum, including first base, where we ideally would have a tall, agile player who would otherwise be playing basketball or tennis, who would be well suited to stretch for errant throws but also be able to get to balls laterally. First basemen could focus all their time and energy on optimally fielding the position without having to expend any valuable time on working on hitting, leaving that entirely to their corresponding “designated” hitter.

The absurdity of replacing every incompetent hitter with a potentially better designated hitter makes only marginally more sense for pitchers than it does for any other position in baseball. Playing shortstop at a high level requires a very complex skill set that is mutually exclusive from the skill set required to hit major league pitching, similar to pitchers who also have to master a complex skill set that does not help them hit major league pitching. If we accept that pitchers should have a designated hitter, we should accept that shortstops should also have a designated hitter, which would suggest that second baseman should as well, since as the header suggests, it’s “turtles all the way down.”

The Argument for Tradition

Tradition, on its own, is not necessarily a good thing, especially in situations such as the “traditional” role of women or people of color in society, or the exclusion of arbitrary matrimonial gender pairings, where tradition is a direct impediment to necessary, vital cultural progress. Such is not the case with respect to the designated hitter rule, which since its introduction in 1973 potentially has led to the regression of pitchers being able to handle major league pitching (more on that later).

The other forms of tradition, such as tailgating at an NFL game, Hockey Night in Canada, NBA Christmas Day, etc., all add flavor and depth to our collective sporting experience. The DH countervails part of the rich tradition of major league baseball–specifically the history of pitchers hitting for themselves–and is a constant buttress against this history.

The argument for tradition goes beyond the theory that the history of the game should be conserved. It speaks to the essence of baseball, which is that every position is unique, with its own strengths, weaknesses and trade-offs, and there shouldn’t be one position singled out that requires two individuals to share the role.

Baseball is the one team sport in which each athlete can be held accountable for the bulk of his individual performance. We should celebrate that and hold pitchers accountable for their ability or inability to hit their position. The other aspect of this argument pertains to the concept that each hitter should, at some level, be able to play the other side of the game. Having a designated hitter with no defensive responsibilities runs anathema to this concept.

A (Short) Visual Case for Eliminating the DH

Pitchers, relatively speaking, used to be better at hitting home runs, with a significant decline since the introduction of the DH. Earlier, we touched upon the potential macro effect the DH has had on pitchers’ collective hitting ability. Let’s take a look at some data, paying attention to pre-DH and post-DH numbers:

Pitcher wRC / 100 PA

Based on wRC, pitchers have been declining for quite a while, with a small bump post-DH (possibly due to better hitting pitchers switching to the NL), followed by the continuing decline of pitcher wRC. It’s difficult to blame the DH rule for this decline since it clearly started before the DH rule was instituted. wRC is a relative stat, and in this case it could be quite difficult to parse out true ability from relative ability. With this in mind, I wanted to take a look at a binary, non-relative metric–home runs per 100 plate appearances–to see if the DH had any effect on pitchers’ ability to hit homers.

Pitcher HR/100 PA

The top and bottom are showing the same data, with the top split out into decades and the bottom into individual seasons. Here we have a very clear signal, with pitchers in the two decades prior to the DH rule being implemented hitting far more HR/PA than any other decade since, with a particularly steep decline in the three decades directly after the rule adoption, which includes both home run “boom” periods.

This year’s 0.523 HR/100 PA during a historic season for long balls is still below the average in the 1963-1972 time period, when pitchers were expected to contribute offensively. These data support the theory that a large element of why pitchers don’t hit well is the lack of expectations placed upon pitchers to contribute on the offensive side of the ball.

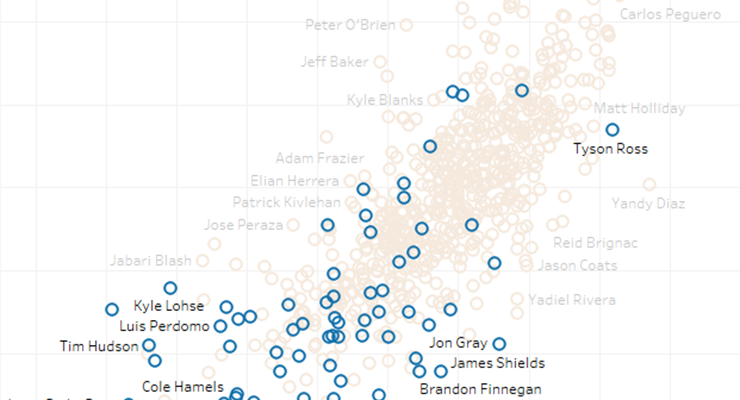

Distribution of Pitcher & Hitter expected WOBA

(Excludes bunts, minimum 25 balls in play during StatCast era)

In yesterday’s piece, we spent an extensive amount of time focusing on the big picture that pitchers can’t compete on the offensive side of the ball. Here we’ll look at the distribution of expected wOBA based on the exit velocity and launch angle.

On the hitter side (i.e., all non-pitchers) we see that roughly six percent of all hitters have an xwOBA below .270 and approximately 19 percent are below .300. On the pitcher side, the average pitcher would thus equate to a fifth-percentile hitter, with the top 10 percent of pitchers very close to average.

Keep in mind, this is only for situations when the ball is put in play, thus focusing more on pure hitting ability (damage done on contact) rather than experience (working counts, pitch recognition, etc), implying that if pitchers were to focus more on their hitting, a healthy percentage would be acceptable major league hitters.

A Short Rant about Manipulating Data Visualizations

I’m going to show you three graphs, one of which was part of yesterday’s piece and showed exit velocity compared to xwOBA, to show how often pitchers are at the low end of both metrics. All three visuals will show the exact same data. With only slight variations, however, the stories they tell will be radically different.

Visual No. 1 | Exit Velocity and xwOBA, Hitters on Top

This is the chart used in yesterday’s piece, with all the blue pitcher circles buried behind the orange hitter circles, leaving the visual impression that there were relatively few pitchers in the middle-middle section of the graph (i.e. somewhat average). This is what happens when we flip the pitchers on top.

Visual No. 2 | Exit Velocity and xwOBA, Pitchers on Top

With the same visual, we can now construct the narrative that while there are a host of pitchers that are just plain horrible, a strong portion of them are comfortably middle-middle and resemble (when they make contact) normal major league hitters.

Visual No. 3 | Exit Velocity and xwOBA, Focus on Pitchers

In this version, we’ve focused on just the pitchers, bringing them to the foreground and fading out all the hitter circles. This shows that pitchers seem to distribute themselves all over the chart, with the bulk clusterd around the 84 mph, .240-to-.270 xwOBA mark (similar to the chart above). This chart–combined with the distribution chart–supports the theory that pitchers are capable hitters who are being dragged down by a host of pitchers who just don’t event try. Thus, we shouldn’t adopt the DH because a lot of pitchers don’t try; we should eliminate the DH and provide more incentive for pitchers to improve as hitters.

Conclusion

The existence of the designated hitter in the American League provides a constant competitive disincentive for pitchers and organizations to invest in developing their pitchers as hitters. While it is hard to prove the DH is completely at fault for the continuous decline of pitcher hitting ability, there really is no compelling pure baseball reason for continued use of the rule.

Even if we accept the fallacious assumption that pitchers don’t hit very well (enough hit well enough when they make contact), it does not imply that they can’t. Further, it would stand to reason that if any position were to fall too far on the wRC+ ladder, it could be subjected to the DH rule, further distorting the game from what it should be: one player per position at one point in time, not one player for eight positions and two players for one specific position.

It’s time for all pitchers to hit for themselves. Let’s designate the DH rule for assignment.

It really would help keep the pace of play nice and brisk too.

This is spot on. That guy yesterday didn’t know anything!

Also, pitchers rarely hit in the minors. If they were forced to hit all the way through their development they would indeed be better hitters

I understand the desire to continually write articles about why the game is better without the DH, but the reality is that it’s never going away. The player’s union would never negotiate a contract that was essentially taking jobs away from players, i.e. aging sluggers who can’t play the field anymore. The DH is here to stay forever, NL fans should just be happy it hasn’t been implemented for their teams yet.

This reads like the poor guy in debate class who drew the short straw and has to defend the indefensible topic. “If an infinite number of monkeys with an infinite number of typewriters could duplicate Shakespeare, then major league pitchers should be able to hit a baseball with regularity.” Except the statistics prove otherwise and have for decades. There’s no smoking gun/alternative universe here.

Since every form of baseball from Little League to the American League uses the designated hitter — with the exception of the National League — this whole issue is moot. You want to be Don Quixote tilting at windmills? Throw up all the graphs and diagrams you want and blather about “possible competitive advantage,” but pitchers are becoming increasingly more futile with a bat in their hands.

Traditions are great, until they no longer serve any use. If the NL wants to enjoy horse and buggy baseball in the 21st Century, that’s their choice. But the modern game is here to stay.

Plus, I’ve never met a single person who buys a ticket to a baseball game to watch pitchers come to bat, even if it’s Bartolo Colon.

1. This author never argues that pitchers are as good as their fellow position players, only that were they incentivized to return to the former average they would fit naturally on the offense-defense tradeoff spectrum (where their pitching ability would compensate for their poor albeit not non-existent value at the plate).

2. That something has been widely accepted as practice does not make it useless to argue against. The argument that unions would never allow the DH to be eliminated is probably correct, but the whole issue isn’t moot just because its fighting a losing battle (a battle being lost largely for reasons that don’t counter the points here)

3. I’ve also never met someone who bought a ticket to specifically watch the DH hit.

It’s just that your team has never been that bad. In 2010 and 2011 I listened to Twins games to listen to Jim Thome hit.

I grew up a Twins fan and am now a Nats fan. I used to think the pitcher batting was really stupid. I now like NL play more–even though the Nats are basically an AL team that is in the wrong league.

My preference for NL play is, unfortunately, ineffable. So, I’ll stop typing.

I agree with the argument to eliminate the DH. However, not because “pitchers should hit,” but because all hitters should contribute somewhere on defense.

To cite a few quotes from the article that I find questionable given the 2017 baseball pipeline from LL to The Show.

“Further, the societal expectation that pitchers don’t need to be good hitters percolates throughout the baseball development system, all the way down to Little League, where, if you are a great pitcher, little emphasis is placed on being a great hitter.”

The best pitchers in Little League are often in the upper echelon of hitters. Truly elite pitching is not projectable until around the age of 14, and it is at this time that the “Pitcher Only” becomes commonplace. At an elite high school, showcase, or college program, these “Pitcher Only’s” spend MUCH of practice doing band work, running, swimming, throwing regimented long toss, or doing other things to protect their arms. They do this in order to best protect their arms, as we try to combat the strain of the modern pitching mechanic on rotator cuffs and UCL’s.

“A player who can throw a ball 90+ mph with enough coordination and accuracy to get it into small target 60 feet away has the requisite physical tools to hit major league pitching.”

This is a bit farfetched. “Players who can throw the ball 90+ MPH with enough coordination to get it into a small target 60 feet away” include a great deal of DI pitchers. Most DI hitters cannot hit MLB pitching, and by this assumption college pitchers (if given the opportunity to remain hitters) would have been better suited as hitters than the hitters themselves.

With the exception of hip-shoulder-separation and coordination (of quite different kinds), there is little in common between what it takes to hit MLB pitching and what it takes to “throw a ball 90+ mph.”

Thanks for writing. Just wanted to take a second and highlight a couple of comments comments and shed a different angle on the issue.

For me to accept a DH, you must first persuade me that professional players deserve a handicap.

High school players can have a handicap. College, sure. Minors, even. But the highest league in the world?

If the highest league in the world, with presumably the best players in the world, requires a handicap in order to compete, something has gone very, very wrong. So, if anyone is in favor of this DH, you must first successfully argue that the best players in the world require a handicap in order to compete.

To me, I’d much rather watch a game without a handicap. Let the best players win.

“A player who can throw a ball 90+ mph with enough coordination and accuracy to get it into small target 60 feet away has the requisite physical tools to hit major league pitching.”

This is not true. In 1962 Bob Buhl, playing for the Braves and Cubs, went 0 for the season. He did, though, manage to reach first base six times by base on balls. In 953 lifetime plate appearances he is credited with 76 hits, for a batting average of, as Skip Carey was so fond of saying, “Oh eighty nine. BINGO!”

A HOF pitcher named Sanford Koufax was another “BINGO” “hitter.” He hit OH ninety seven lifetime. Sandy did, though, have to balls the chicks love…

For those who posit, “The DH is here to stay forever,” I say the DH was called an “experiment” when instituted, and it is an “experiment” that has lasted far too long. It is an “experiment” that went awry. It has drastically altered the way the game is played. Only those who want to see longer bullpen benches filled with yet another “loogy” like having a DH.

If one extrapolates where MLB is heading, then it will go the route of the NFL. Younger fans do not believe it when informed that football (maimball) had two-way players, who played both offense and defense, until the ’60s. The only stopping better fielding SSs from only playing in the field is the cost of adding more players to the roster. I would prefer to see an astute manager, like Bobby Cox did with Jeff Blauser, an above average hitting, below average fielding, SS, who was paired with Raffy Belliard, a very good fielding, but not so good hitting SS. It was remarkable to watch Bobby game after game utilizing both players to obtain the best out of their abilities.

That should be “Sandy did, though, have TWO balls the chicks love…

” It’s difficult to blame the DH rule for this decline since it clearly started before the DH rule was instituted.”

This was the point at which the author needed to stop, recognize that “well, this theory didn’t pan out,” and scrap his article. Unfortunately, instead of accepting the obvious implications of the historical pitcher wRC chart above, and calling it a day, the author persisted.

If we respect the data, the story is pretty clear: The decline in pitchers’ hitting relative to position players began 100 years ago and proceeded relentlessly since then, with the DH rule having no discernable impact. This trend has little to do with pitchers’ training or attitude — it simply reflects the reality that professional hitters are getting better all the time. As a result, the gap between them and a good athlete who is not a professional hitter (AKA “MLB pitchers”) grows ever larger. The story is not “pitchers keep getting worse at hitting” (which is almost certainly not true), but rather “position players keep getting better at hitting.” And once you understand that, it becomes obvious that there is absolutely nothing pitchers could do to materially close the gap.

There is a balance between defense and offense for every position. However the effect that pitchers have on run prevention mean that hitting will always pale in comparison in terms of importance for them.

Also Starting pitchers only play one game out of every five and average about 2 PA per game. Starting position players play 9 innings almost every day and average about 4 PA per game. All told, regular position players get 9 times the PA of starting pitchers.

“A player who can throw a ball 90+ mph with enough coordination and accuracy to get it into small target 60 feet away has the requisite physical tools to hit major league pitching.”

“This is a bit farfetched. “Players who can throw the ball 90+ MPH with enough coordination to get it into a small target 60 feet away” include a great deal of DI pitchers. Most DI hitters cannot hit MLB pitching, and by this assumption college pitchers (if given the opportunity to remain hitters) would have been better suited as hitters than the hitters themselves.”

Actually, I think that is a very good observation by Eli. It’s not that all pitchers should be able to hit .250 or something. Obviously they can’t, and for that matter most professional hitters can’t hit that well against MLB pitching.

But despite the fact that pitchers were not selected for hitting ability, they can all hit at least something. Even Jon Lester, who began his career with a huge 0-for streak, is hitting .136 this year and even has a homerun. Pitchers are far below average hitters, but there are almost no examples of pitchers who cannot hit at all given a big enough sample size. Perhaps the worst would be Dean Chance, who hit .066 in 662 AB.

Pitchers are far better at hitting than the average 20-40 year old non-athlete reading this would be. I doubt among the non-athletes you could find 1 person in 100 who could hit .100 against major league pitching.

Among non-athletes, I absolutely couldn’t find 1 person in 100 who could hit .100 against major league pitching. I’d go as far to argue that given a pool of non-baseball playing athletes, I couldn’t find 1 person in 100 who could hit .100 against an MLB pitcher.

That was not Eli’s argument, though, and “pitchers are worse hitters than average people” wasn’t mine.

He drew a correlation between the skills required to “throw a baseball 90 MPH” and the sills required to “hit MLB pitching.” That is not a well founded argument. Some pitchers are not great hitters because the skills of pitching and hitting at that level are somehow biomechanically intertwined with one another. These hit well because they’re incredible baseball players and have been around the game for a long time, at a high level.

We will not have pitchers taking OF-BP in lieu of band work, regimented long toss/pen work, and swimming. There are many great arguments against the DH. The argument that we should allow top flight pitchers to hit OF-BP with the rest of a high level college/pro team, and shouldn’t force them to focus on pitching and the safety of their arms, is not a compelling one.

^^The pitchers that are great hitters are not so because the skills of pitching and hitting at that level are somehow biomechanically intertwined with one another. They hit well because they’re incredible baseball players and have been around the game for a long time, at a high level.^^

I apologize.

Thanks for the response, by the way. Love discussing this sort of thing!

I definitely feel like I’m in the minority but I enjoy having the DH in the AL and no DH in the NL as otherwise there’s not really any difference between the two leagues any longer.

That said I enjoyed both articles.

The bigger issue is with starting pitchers getting hurt. They are paid MUCH more nowadays then they were in the 1950’s and you would rather hope to avoid non-pitching injuries, like running the bases, and focus their training to reduce injury.

The high cost of starting pitcher salaries is why the DH makes competitive sense in today’s luxury tax baseball system.

“Pitchers are far better at hitting than the average 20-40 year old non-athlete reading this would be.”

That’s definitely true. After all, these are elite athletes, most of whom have played baseball since they were 5-6 years old — it would be shocking if they couldn’t hit better than the average man of their age. But I think the relevant question is whether they hit well enough — close enough to a weak-hitting position player — that we fans want to pay to watch them hit. Obviously, opinions will differ. But as the data from the first article showed, pitchers are not just weak hitters, they hit far worse than a weak hitting position player. There literally isn’t a single position player who hits as poorly as the average pitcher.

Fundamentally, pitchers are being asked to do something (hit) that played no role in their being selected to do this job. Do we allow that to happen routinely in any other situation in baseball? I can’t think of any. What about in other sports? The closest I can think of is asking big men to shoot free throws in the NBA. But even that isn’t nearly as bad asking pitchers to hit. Even Shaq made 53% of his FTs (about 75% of league average), not the level of futility we see from pitchers. And a big man’s ability to shoot does play a role in whether he gets to play in the NBA. A true parallel would be if we forced centers to take 20% of their team’s three-point attempts, or required catchers to make 1/9 of their team’s stolen base attempts. A well-designed sport does not require athletes to do things at which they are fundamentally incompetent (by the standards of that sport). Making MLB pitchers hit is, if not the unique exception, close to it.

Guy: “Fundamentally, pitchers are being asked to do something (hit) that played no role in their being selected to do this job. Do we allow that to happen routinely in any other situation in baseball?”

Every four years.

I guess that’s not really in baseball. Busy morning. Just go back to ignoring me.

During todaze ongoing game between the Braves and Phils there was this exchange:

Jim: “It is possible to swing and miss on purpose.”

Dandy Don Sutton: “It is, and I proved that many times.”

Have you taken into consideration how many times a pitcher has intentionally left the bat on his shoulder, sometimes when given the order by the manager; sometimes when he takes it upon himself?

The problem is that development of any process causes moves toward specialization. If you want pitchers to hit more, the other side would have to be fighting the pitcher-hitter specialization split by making position players pitch as well. You would also have to have pitchers playing another position a given part of the time. Baseball played this way could add powerful strategy. If you had your primary starting pitcher, a righty, pitching, and a secondary pitcher, a competent hitter and outfielder, playing right field, you could switch them in optimal platoon situations without burning bench and bullpen. You could spread out the wear and tear on pitching arms and the dreary waste of time on pitching changes. If you say that is artificial, so is the NBA rule against zone defenses. Maybe shifts should be outlawed as well. I’m still thinking about that. In the NL the counterpart of the DH, which didn’t use to be used so much, is the double-switch. That is also an artifice to prevent the pitcher from batting. If the pitchers were more decent hitters, none of this would be necessary.

Terrific piece of satire, Eli. You had me chuckling throughout. You are an expert troll. Thanks.

I understand the draw to tradition, but not all pitchers are, as the article seems to try to suggest, certainly capable of being good hitters.

Furthermore, if baseball had originally been created with a DH for the pitchers and 100 years later somebody said, “Hey, I have an idea! let’s have the pitcher bat!”, well, everyone would think that person was an idiot.

With starting pitchers rarely going more than 6 innings, a pitcher may at two times a game ,& if he bats a third time, his team is probably winning. Some of the at bats are sacrifice bunts. Scoring in the NL has kept up with the AL

Argument seems to hinge strongly on the idea that pitchers could be better hitters if they put more time into practicing, but why isn’t this happening in the NL? Even if you can prove that NL pitchers hit a little better than AL pitchers in interleague, the NL pitchers are much worse hitters than position players in either league. So whether or not pitchers could theoretically hit better due to untapped hand-eye-coordination-based talent, it’s just not happening.

So if pitchers are going to continue to be far worse hitters than position players, I’d prefer to see the best bench bat get the ABs. Teams roster plenty of prospects waiting for a chance to break out and I’d prefer to see them get the opportunity rather than watching a pitcher struggle. No matter what, someone is going to be sitting on the bench instead of hitting 9th, so there’s a cost either way.

And I’ve heard the argument about how the NL game is more interesting because you have to think more about substitutions, but I just don’t buy it. A pitcher sacrifice bunting or a manger double-switching just isn’t that strategically interesting to me.

BOTTOM LINE: I don’t like the fact that 1/9 ABs are a very high probability out. Instead of trying to make the games faster, let’s make them more interesting. Remove this gameplay cruft.

It’s more like 1/20 ABs, not 1/9, due precisely to the extra layer(s) of strategy that weak-hitting pitchers give to the NL game. Just looking at the 2017 stats of my hometown Pirates, 237 of 4674 ABs (5%) have been pitchers.