The Pyramid Rating System All-Time League and the All-Time Baltimore Orioles

Earl Weaver was the easy selection to be the manager of the all-time Orioles. (via Keith Allison)

As mentioned in my first article here last year, one of the side projects I have done with the Pyramid Rating System is the creation of an all-time roster for each active franchise in the majors (as well as a few non-active franchises). The selections of the all-time rosters are based largely on the “team” rankings of the Pyramid Rating System, where players with individual franchises have been ranked. i.e., Babe Ruth with the Yankees versus Babe Ruth with the Red Sox.

The inspiration for this came largely from the Great American Fantasy League, of which I am a member of as manager/owner of the Chicago Cubs. If you go to the 31-minute mark of the video embedded below you will see a feature MLB Network did on the league as part of their “Behind The Seams” series.

The other inspiration has come from seeing what others have done with this topic. Obviously, the idea of an all-time team for a single franchise is nothing new, but what I find in most every article I read about this topic is that the author rarely address the topic of how actual baseball strategy would affect how the team is run: how to set a lineup and a depth chart, playing guys out of their natural position, platoons, having a ready backup at every position in case of injury. These are factors that managers and general managers have to contend with daily basis that for the most part I feel get swept under the rug.

The idea behind this is not just to imagine what each of these teams would like look on its own but also to mirror what the Great American Fantasy League does, and put each of the teams in context of what a whole league of all-time teams would like look. What I’ve tried to do with each of these franchises is build a team and a strategy behind it for a 162-game regular season as opposed to just simply naming off the best players at each position, or just listing the best season a player had at each position.

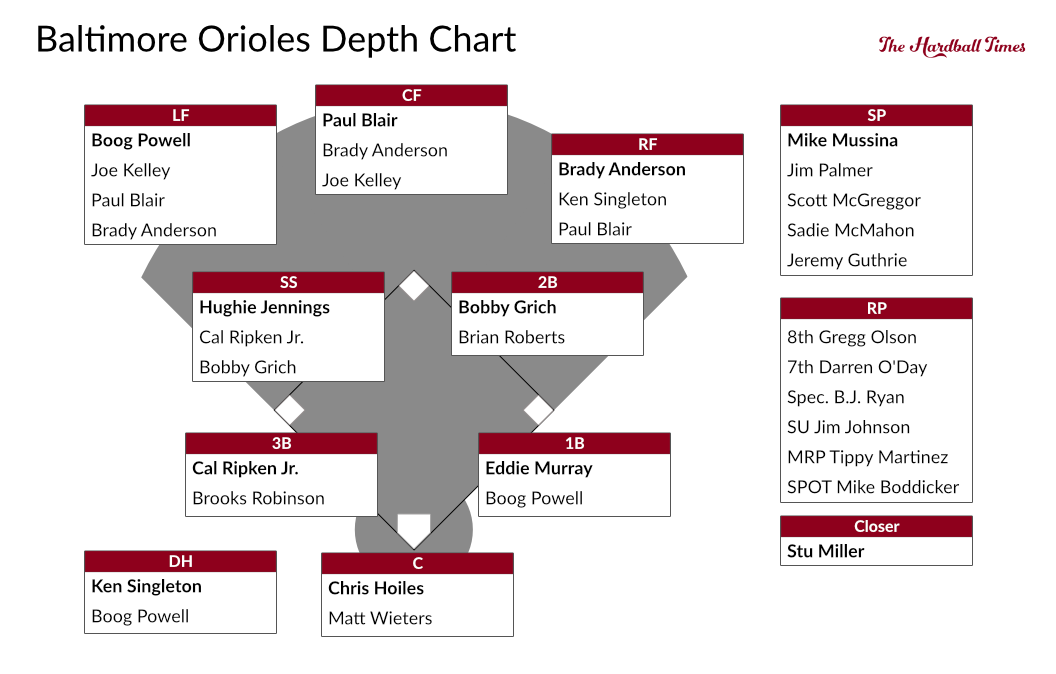

We see it in the majors all the time. Just because someone is the best center fielder on the team doesn’t automatically mean he will be the full-time starting center fielder. If I have a great defensive backup but a bad left fielder, I may shift my All-Star center fielder over to left, not because I don’t think of him as a great center fielder, but because I’m trying to cover a weakness on the team. On a different team, the same player may be the full-time starting center fielder. No manager or GM would ever look at a player’s strengths or weaknesses independent of the rest of the team in determining what role he should play, and that is the approach I have taken here.

Another caveat I tried to include was to show how these teams would be built if they were to exist today with the game played as it is today. Every roster will feature 12 pitchers–five starters, six relievers and a spot starter who could also act as a long reliever–and just 13 position players, two of whom have to be catchers.

The overall strengths and weaknesses of each era will be reflected in how the players on the roster will be used. Bullpens will tend to be disproportionately composed of modern-day players, and rarely will you see a Deadball era player batting in the middle of the order.

For the positions at which players can be listed, I tried to focus more on what positions a player could have played during his career than the positions he did play. For example, I believe Ernie Banks could have spent his entire career playing first base and still would have had a Hall of Fame career. Same could be said for Mickey Mantle if he had been a first baseman throughout his entire career.

These types of assumptions, though, are always going to be made on historical evidence. You will never see a player like Ted Williams listed at third base. Generally speaking, a player had to play at least 10-11 percent of his total games with the team at a position to considered an option at that position, with the exception of catcher, where the threshold was roughly 15 percent.

The only exception I made to this rule was when it came to the outfield. Anyone whose primary position is listed as center field is automatically eligible to play both left and right field regardless of if he played there. So Willie Mays, Mantle, Ken Griffey Jr., Joe DiMaggio and Duke Snider are eligible at all three outfield positions in spite of their limited playing time at the corners.

A similar assumption was made for players whose primary position is listed as right field but who would also played enough games to qualify to be listed as a center fielder. These players also are eligible to be listed as a left fielder. (i.e. Hank Aaron, Al Kaline, Reggie Jackson, Sammy Sosa, etc.) In essence, this follows the Bill James defensive spectrum, but applied only to outfield.

Like the spectrum, it does not go the other way around. Someone whose primary position was left field and who qualifies as a center fielder does not automatically qualify to play right field. Tim Raines, for example, can not be used as a right fielder. Similarly, anyone who qualifies as both a left and right fielder does not automatically qualify as a center fielder. Billy Williams and Ryan Braun, for instance, can not be listed as a center fielders.

Adding these aspects gives a much better view of what you actually could do with a team as opposed to relying solely on historical stats as the be-all, end-all.

As far as the teams themselves go and my proposed “league,” here is what is included:

| AL East | NL East |

| Baltimore Orioles | Boston Braves |

| Boston Red Sox | Brooklyn Dodgers |

| New York Yankees | Montreal Expos |

| Philadelphia Athletics | New York Giants |

| Toronto Blue Jays | New York Mets |

| Washington Nationals | Philadelphia Phillies |

| AL Central | NL Central |

| Chicago White Sox | Atlanta Braves |

| Cleveland Indians | Chicago Cubs |

| Detroit Tigers | Cincinnati Reds |

| Milwaukee Brewers | Miami Marlins |

| St. Louis Browns | Pittsburgh Pirates |

| Tampa Bay Rays | St. Louis Cardinals |

| AL West | NL West |

| California Angels | Arizona Diamondbacks |

| Kansas City Royals | Colorado Rockies |

| Minnesota Twins | Houston Astros |

| Oakland Athletics | Los Angeles Dodgers |

| Seattle Mariners | San Diego Padres |

| Texas Rangers | San Francisco Giants |

As you can see, a few teams listed–such as the Brooklyn Dodgers and Philadelphia Athletics– no longer exist. That is because the franchise histories I am using do not follow the traditional major league timeline. As seen in the video at that start, Walter Johnson is part of the all-time Twins in the Great American Fantasy League, but in my league he is on the all-time Washington Nationals. The idea behind this is to follow more of a “city-centric” approach than going by actual franchise history.

Johnson is a good example of the problems of looking at past players from bygone franchises in the context of their more modern counterparts. Johnson may never have played a single game for the Nationals, but he never played a single game for the Twins, either. Johnson did, however, play his entire career in Washington, and in my opinion it’s the city identification that matters more than the franchise. In this regard, I’m taking an approach more akin to what the NFL did with the Cleveland Browns. Nobody would ever think to put Jim Brown or Otto Graham on the all-time Ravens squad even though that is the team that version of the Browns ultimately became.

Even this approach is met with some issues. While the Minnesota Twins all but ignore their tenure in D.C., both the Dodgers and Giants are very open about honoring their prior history in New York. The Atlanta Braves seem to be somewhere in the middle in terms of how much they’ve acknowledged their past in both Boston and Milwaukee. How much of a team’s history belongs to the city and how much of it belongs to the franchise’s own lineage seems very much open for debate with no clear answer.

The six defunct franchises I included — the Boston Braves, Brooklyn Dodgers, Montreal Expos, New York Giants, Philadelphia Athletics and St. Louis Browns — are all teams I feel can have their own separate history independent of any currently active team. For teams like the old Washington Senators, the Milwaukee Braves and the Kansas City Athletics, I’ve included them with their current major league counterparts who play in the same cities they once did. The rationale is that, if the Milwaukee Braves never had moved to Atlanta, the Brewers never would have existed; however, even if the Braves had never left Milwaukee, it’s likely that one way or another, Atlanta eventually would have been able to land a major league team.

The final caveat I included in an effort to have this system resemble more of an actual league than an evaluation of great players in a team’s history is that I can use each player only once. Obviously, there are players whose talent would qualify them for multiple franchises. In terms of placing players using this method, I tried to factor in where a player had his best years and his overall playing time. For instance, I thought Keith Hernandez had his best years with the St. Louis Cardinals, but because of the depth the Cardinals have at first base, they actually can afford to leave the ’79 MVP off the 25-man roster. The New York Mets, however, are not as deep at first base, which is where Hernandez winds up.

As a bonus, I included full 40-man rosters as well as a full coaching staff. What I find interesting about the 40-man rosters is that in some cases they actually can act as a “minor” league of sorts–a lot of active players who may be right on the cusp of making the 25-man roster but are perhaps just a solid year or two short. Please note that as of now these teams include stats through 2015.

As for the coaching staffs, the managers and bench coaches were the No. 1 and No. 2 ranked managers in a franchise’s history. The rest of the coaching staffs were largely suggestive and shouldn’t be taken too seriously. Where possible, I tried to bring in elements of realism, but it is very difficult if not impossible to determine something like who was the greatest first-base coach of all time. For the most part, I simply tried to identify players with elements that would match up with the skills required to be an effective coach at each position but who themselves would have no chance of making the 40-man all-time roster, meaning none of the coaches are currently active players. As such, take these with a grain of salt.

The final issue in the setup is in which year to begin, and that is 1891. Why 1891? First, it’s the first year for which Baseball-Reference provides neutralized stats, and it’s also about the time when the game of baseball really started to take its modern form. The Pyramid Rating System lists Ross Barnes as the 39th-greatest player in baseball history, but in reality I would consider someone like him to be inconclusive in terms of an all-time rank because of the vast rules differences of the era. The 1891 season is also early enough to include peak years for players like Cy Young, whom many still consider to be the greatest pitcher of all time.

Including the 1890s, as well as histories of bygone franchises that played in the same city, changes the dynamic of how some of these teams otherwise would look. One such franchise is the first I am doing, the Baltimore Orioles. Most view the late 1960s and early ’70s as the Golden Era of baseball in Baltimore, an era that saw the Orioles win three straight AL pennants, but it was not the first dynasty the city had ever seen. That would be the National League’s version of the Baltimore Orioles in the 1890s, a team that would win three pennants in a row behind Ned Hanlon and featured such future Hall of Famers as Hughie Jennings, Joe Kelley, Willie Keeler and John McGraw.

Baltimore Orioles

Franchises Included: (Baltimore Orioles (AA) 1891, Baltimore Orioles (NL) 1892-1899, Baltimore Orioles (AL) 1901-1902, Baltimore Orioles (AL) 1954-Present)

Number of Hall of Famers on 25-man roster: 6

Manager: Earl Weaver

Although Hanlon and his three NL titles could pose a decent argument, nobody can argue with the success of Earl Weaver. Over his 17 seasons in Baltimore, the Orioles experienced just one losing season under Weaver and had only four seasons in which they finished lower than third in the division. This type of success is reflected in the roster selection, as nearly half of the 25-man roster played under Weaver.

The number of managers who had a more successful tenure with one team as Weaver had with the Orioles could be counted on one hand, with fingers left over. It is because of this that Weaver is in the Hall of Fame and an easy selection for manager of the all-time Orioles, which is saying something considering the success of Hanlon’s tenure in Baltimore landed the man they called “Foxy Ned” in Cooperstown.

Best overall player, hitter and position player: Cal Ripken Jr.

In my opinion, the greatest shortstop in American League history. Few players in history have had more success with one team than Ripken had with the Orioles. Over a 21-year career in Baltimore, Ripken racked up two MVP awards, eight Silver Sluggers, over 3,000 hits, over 400 home runs and an incredible 19 All-Star selections. As great a hitter as Ripken was, the amazing thing is, it could be argued the best part of Ripken’s game was his defense. Although he won just two Gold Gloves in his career, Ripken probably should have had a lot more, as he was either first or second in defensive WAR in the AL eight times during his career and is fourth all-time.

With Ripken playing 675 out of his 3,001 career games (22.5 percent) at third base, he qualifies to play both third base and shortstop, and I consider him the best option at both positions. Even if we assume Ripken would be a worse defensive player at third, its still worth noting that he still has over 3,000 hits and 400 home runs for his career, something no career third baseman can say. And every single one of those hits and home runs came with the Orioles over the course of more than two decades.

Best pitcher: Mike Mussina (Honorable Mention – Jim Palmer)

Although I have Mike Mussina ranked as the best Baltimore pitcher of all time, a 1 and 1A rank would be much more reflective of how close these two are than a 1-2 rank.

People are well aware of Jim Palmer. A three-time Cy Young award winner and the ace of the Orioles staff for the better part of 19 big league seasons, Palmer carries exactly the type of resume you would expect to see from a first-ballot Hall of Famer. Palmer was among the top 10 in the AL in ERA 10 times, in WHIP nine times, innings pitched eight times, strikeouts seven times and pitching WAR eight times. It is for all these reasons that I think Palmer is one of the best number-two starters on any team’s all-time roster.

What hurts Palmer, and why there aren’t more Orioles pitchers from his era on the team, is the same reason I feel Palmer is slightly overrated. Bill James said “a great deal of what is perceived as being pitching is in fact defense,” and that is what happened with Orioles of the late ’60s and ’70s. With Brooks Robinson, Mark Belanger, Paul Blair and Bobby Grich playing behind Palmer and company, there is no doubt that some of the numbers Orioles pitchers were able to put up in this era were inflated by the defense behind them.

This doesn’t mean I don’t view Palmer as a Hall of Fame-caliber pitcher. It’s just naïve to think Robinson, Blair and company didn’t have something to do with Palmer’s 2.58 ERA for the decade. It’s a combination of a great pitcher and a great defense.

This reliance on excellent defense is the key reason Mussina becomes virtually equal to Palmer. In Fielding Independent Pitching (FIP), Mussina is actually top 10 in the AL more frequently with the Orioles than Palmer was for his entire career (seven times versus five), including being in the top three three times versus Palmer’s one. Also, in walk-to-strikeout ratio Mussina was among the top 10 in the AL nine times with the Orioles versus Palmer’s two top-10 appearances. Even though Palmer was more successful than Mussina by traditional stats, this also was in large part due to the era Palmer pitched in compared to Mussina’s.

As for Mussina, I feel he is one of the most criminally underrated pitchers in history. For his entire career, Mussina was in the top 10 in ERA 11 times. By comparison, Bob Gibson was among the top 10 in ERA eight times, and nobody ever would question Gibson’s worthiness of enshrinement. If not for the One Team Only rule, Mussina would be on the all-time Yankees roster as well.

Best player not on the roster due to the One Team Only rule: Frank Robinson

A former Triple Crown winner and a five-time All-Star, Frank Robinson is arguably the greatest outfielder in Orioles history. On this team, Robinson would have bolstered the lineup in a big way, especially against lefties, an area where the Orioles’ right field starter, Brady Anderson, struggles.

As great as Robinson was with the Orioles, his best years came in Cincinnati, a place where he led the NL in OPS three straight seasons to go along with 161 steals and a Gold Glove, elements of Robinson’s game that were greatly reduced by the time he got to Baltimore.

For much of his tenure in Baltimore, Robinson was a one-dimensional player, but a one-dimensional player who also was capable of smashing 30 home runs in an era when 30 home runs was good enough to be in the top 10 in the league. The One Team Only rule takes out what otherwise would have been a middle-of-the-lineup presence for the Orioles.

The rule comes into play in other areas with the team. Below, you will see Miguel Tejada listed as an Orioles reserve, which means he’s not on the Oakland roster, which you might think odd. I sort of agree. I have him listed as the second-best shortstop in A’s history after Bert Campaneris. The problem with the A’s is all their starting infielders (Jason Giambi/Mark McGwire, Mark Ellis, Campaneris and Sal Bando) can only play one infield position. Giambi and McGwire takes care of first, but I need a fourth outfielder (Jose Canseco) and a backup catcher (Kurt Suzuki).

That leaves me with two bench spots for three positions. If I added Tejada to the team I would need someone who could play both third and second. There’s really nobody like that. I can however find someone in Mike Bordick who can play short and second and just put Eric Chavez at third. This is made a bit easier by the fact that Tejada was just as good in Baltimore — if not better — than he was in Oakland, even though many fans from his heyday probably think of him as an Athletic first.

Putting Bordick on Oakland also works us back to Baltimore. Bordick had more success in Baltimore, but he is squeezed off the roster. Bordick is limited to shortstop only with Baltimore, and that’s a very deep position. Here’s how the O’s line up at shortstop:

- Cal Ripken Jr.

- Hughie Jennings

- Bobby Grich

- John McGraw (On the NY Giants as manager)

- Mark Belanger

- Miguel Tejada

- Melvin Mora

- J.J. Hardy

- Luis Aparicio (On the White Sox in my league)

- Mike Bordick

So, if you’re wondering why Bordick isn’t on this Orioles roster, that’s why.

| Position | Person |

| Manager | Earl Weaver |

| Bench Coach | Ned Hanlon |

| Hitting Coach | Merv Rettenmund |

| Pitching Coach | Ray Miller |

| Bullpen Coach | Grant Jackson |

| 1st Base Coach | Jack Doyle |

| 3rd Base Coach | Al Bumbry |

| DH vs RHP | DH vs LHP | ||||||

| Pos | B | T | Name | Pos | B | T | Name |

| DH | S | R | Ken Singleton | 2B | R | R | Bobby Grich |

| LF | L | R | Boog Powell | C | R | R | Chris Hoiles |

| 3B | R | R | Cal Ripken Jr. | 1B | S | R | Eddie Murray |

| 1B | S | R | Eddie Murray | RF | S | R | Ken Singleton |

| RF | L | L | Brady Anderson | 3B | R | R | Cal Ripken Jr. |

| C | R | R | Chris Hoiles | CF | R | R | Paul Blair |

| 2B | R | R | Bobby Grich | LF | R | R | Joe Kelley |

| CF | R | R | Paul Blair | DH | L | R | Boog Powell |

| SS | R | R | Hughie Jennings | SS | R | R | Hughie Jennings |

| vs RHP | vs LHP | ||||||

| Pos | B | T | Name | Pos | B | T | Name |

| RF | S | R | Ken Singleton | 2B | R | R | Bobby Grich |

| LF | L | R | Boog Powell | C | R | R | Chris Hoiles |

| 3B | R | R | Cal Ripken Jr. | 1B | S | R | Eddie Murray |

| 1B | S | R | Eddie Murray | RF | S | R | Ken Singleton |

| CF | L | L | Brady Anderson | 3B | R | R | Cal Ripken Jr. |

| 2B | R | R | Bobby Grich | LF | R | R | Joe Kelley |

| SS | R | R | Hughie Jennings | SS | R | R | Hughie Jennings |

| C | R | R | Chris Hoiles | CF | R | R | Paul Blair |

| P | R | R | Mike Mussina | P | L | R | Mike Mussina |

| Pos | B | T | Name |

| C | R | R | Rick Dempsey |

| 1B | L | R | Chris Davis |

| 2B/3B | R | R | Rich Dauer |

| SS/3B | R | R | Miguel Tejada |

| SS | R | R | Mark Belanger |

| OF | R | R | Adam Jones |

| OF | L | L | Willie Keeler |

| OF | L | L | Nick Markakis |

| SP | L | L | Erik Bedard |

| SP | R | R | Scott Erickson |

| SP | L | L | Mike Flanagan |

| SP | R | L | Dave McNally |

| RP | L | L | Zach Britton |

| RP | R | R | Dick Hall |

| RP | R | R | George Zuverink |

Strengths

Without question, the biggest strength of the Orioles is who they have on the left side of the infield. This is evidenced by the bench role Brooks Robinson plays, which unfortunately is more or less wasted on this team. In my opinion, Robinson is the third-best player on the team, but the two players I have in front of him are Ripken and Jennings. With Ripken, we have not only arguably the greatest shortstop in American League history, but someone who proved his ability to play third base, as well. Robinson is the greatest third baseman in Orioles history, but that may be in part because Ripken played most of his career at short.

Although Robinson was arguably the greatest defensive third baseman of all time, Ripken was one of the all-time defensive greats at short, and it would stand to reason Ripken could have been one of the all-time great defensive third baseman too had he his prime years there, which is what this plan is picturing.

With Jennings, we have one of the more forgotten great players in baseball history. With the Orioles, Jennings batted a career .359, including one year (1895) when he hit .401. Jennings was also first in defensive WAR every year from 1894 to 1896, helping lead the Orioles to the National League title in all three seasons. Of all the great players for Ned Hanlon’s Orioles, Hughie Jennings was the greatest.

Despite having much less power than Robinson, Jennings would be a far better contact hitter and base stealer. Robinson would still have the edge defensively, but not enough to justify benching Jennings in favor of him.

Boog Powell and Brady Anderson also give the lineup a bit of a power boost against righties. During Anderson’s 50-home run season of 1996, his OPS against righties was 1.103. Similarly in 1964, the year Powell led the AL in slugging, he had an OPS of 1.101, which–in the pitching rich year of 1964–was good enough for an ungodly 213 OPS+ against righties.

In spite of his offensive limitations, Paul Blair would have to be considered a leading candidate to win a Gold Glove in this all-time league. Only Ken Griffey Jr. and Al Kaline have won more Gold Gloves as an American League outfielder, and with either Ken Singleton or Powell likely to see fielding time in almost every game, the defensive boost provided by Blair could go a long way in covering that weakness.

The bullpen, while not the best, is certainly one of the better ones in the American League. The emergence of Darren O’Day as one the best setup men in the game has helped solidify this status compared to where it would have been a few years ago. Likewise, the emergence of Zach Britton as one of the game’s best closers could further improve the bullpen, and he sneaks onto the 40-man roster.

Featuring B.J. Ryan as a lefty specialist is one of my favorite little quirks with this team. Although solid throughout his career against righties, Ryan was particularly nasty against lefties. In 2004, lefty opponents managed to hit only .094 against him. For a team built almost solely around right-handed pitching, Ryan could provide a major boost.

Weaknesses

After Mussina and Palmer, the quality of the Orioles starting rotation drops off very quickly, which is surprising for a team that has produced six Cy Young Award winners, but probably not as surprising for a team that has only produced one Hall of Famer over the same time span. For the number of great pitching seasons the Orioles have had over the years, the lack of long-term consistency by any pitcher outside Mussina and Palmer sells them a lot shorter than their team stats might otherwise indicate. As you will see later, some teams are able to go three, four–and in one case–even five Hall of Famers deep with their rotations. When Mussina and Palmer are on the mound, the Orioles are a team capable of beating anyone, but with anyone else it could be a rough go.

As mentioned before, the Orioles are also a very righty-heavy team featuring just two lefties on the 25-man roster, which against a lefty-dominant lineup could spell doom.

In the field, the Orioles are hamstrung by bad defense in the corner outfield positions. With Eddie Murray locked in at first, Powell is forced to play out of position to be in the starting lineup. As bad as Powell might be in left, Singleton is no better in right, but with Anderson’s role being limited to a platoon, it forces Singleton out in right whenever a lefty is starting. This allows the DH spot to open up for Powell, and it slides Joe Kelley — who hit .351 during his Orioles career — into left. But considering the lack of importance left field played defensively in the 1890s relative to today, Kelley may not be much of a defensive upgrade over Powell.

Perhaps the biggest weakness for Baltimore is just the overall lack of superstar power. As great as guys like Murray and Grich were with the Orioles, when compared to what other teams have as their starters, they are middle of the road.

Conclusions

Compared to the rest of the teams, the Orioles are mediocre. Their left side of the infield is second to none, while Blair, Grich and Murray round out a pretty solid defensive team. Mussina and Palmer make for a pretty solid 1-2 punch to go with a solid bullpen.

The biggest downside with Baltimore is its lack of superstar depth. Five Hall of Fame position players may seem like a lot, but other teams can fill almost their entire lineup with Hall of Famers. The corner outfield positions are obvious weak spots, and the starting staff drops off drastically after Mussina and Palmer. Over a full season, my guess is Baltimore would win around 75 games.

The last thing I want to mention is the tremendous amount of talent it took to make any of these teams. Nearly every single player on the Orioles’ 40-man roster was an All-Star. Virtually everyone in the starting lineup was at one point an MVP contender. These are the best of the best, and a lot of the names you see missing from the Orioles may be found on other teams. A squad of the best players ever to suit up for the Orioles would include Robin Roberts, Reggie Jackson and Hoyt Wilhelm, all of whom have made all-time rosters for other franchises.

I hope people enjoy reading about these all-time teams as much as I did making them. This was a two-year process, and there were a lot of tough calls to make. I’m sure I didn’t get every one of them right, and I am sure people will argue that Brooks Robinson at third and Ripken at short is a better combo than Ripken at third and Jennings at short. Just don’t think I’m hating on Robinson — I still consider Robinson to be the greatest defensive third baseman in baseball history, and all three had Hall of Fame careers.

You need to get out more, leaving Frank Robinson off any all time list and putting Ripken over him is crazy.

The only reason Frank Robinson didn’t make the cut is because he is on the reds team(where he had most of his best years), obviously this team would be better with Frank Robinson in right and Brady Anderson/Joe Kelly in left.

The only quibble I have is I think I’d prefer Dempsey for defensive purposes over Hoiles/Wieters.

I think Dempsey is the best defensive catcher the Orioles have ever had, but offensively I’m not even sure he would be in the top five and that’s what winds up costing him. The fact that he’s on the 40 though I think is evidence of how highly I think of Rick Dempsey. Pretty much every person you see on the 40 man roster was a perennial all-star with the Orioles at some point in their career.

What I find interesting about Hoiles is that he actually winds up being one of the most dangerous bats the Orioles have against lefties. From ’93-’95 Hoiiles hit .304 against lefties with 28 home runs, 15 doubles and 67 RBI’s all over just 348 plate appearances. He also had an on base percentage of .414 and an OPS of 1.071 over that time span. In fact Hoiles had an OPS of at least 1 against lefties every year between ’93 and ’95.

Dempsey would be a black hole offensively, and while Dempsey has the edge on Chris defensively, Hoiles was top ten in defensive WAR in ’94, so were not talking about comparing Charles Johnson to Mike Piazza, which is what the difference would have to be for Dempsey to overtake Hoiles.

It wasn’t Ripken over Robinson. You seem to have missed the intent of the list…

Interesting article. Could of suggestions/questions:

George Sisler on first over Boog Powell?

Ken Williams perhaps in the OF?

Could BJ Surhoff help out over Hoiles @ C?

PS Weaver would pick Dempsey over Weiters.

The only reason players like Sisler and Williams are off the list is because I treated the Browns as their own separate franchise independent of the Orioles.

The position measurements are team by team as well, so even though Sufhoff played 704 games behind the plate, 0 of them came with Baltimore so he’s not considered eligible as a catcher with them.

Guys were evaluated strictly by what they did with the team as opposed. The Mets for instance could feature a lineup with Willie Mays, Rickey Henderson and Duke Snider in the outfield, but it wouldn’t be reflective of how great they were with the franchise.

With Dempsey versus Wieters, I think that’s a much closer battle than Dempsey versus Hoiles. Defensively the two are closer together, but such is the case offensively as well. Wieters can at least give you a bit of a power threat which puts him over, but neither I think would be all that great of a hitter.

Wow, this is awesome! What a fantastic series and concept. Looked over the Pyramid Introduction article, really great stuff. I’m looking forward to it. Also, do you plan on posting any all time rankings based on the pyramid curve? What is the schedule for the current series?

Thanks for the feeback. I do have a master list of the team rankings, but as of now I don’t really have any plans on positing it. It was about 27,000 player tenures as opposed to the 13K players I had evaluated in the player rankings. 1440 players made a 40 man roster which works out to a little more than 10% of the total players I had evaluated being featured in this series, which is much more enjoyable for me to talk about then just trying to dial in on the top 1% of players as the be all end all of significant players in history.

As for as a schedule I’m already working on the next team, but there’s a lot of great things featured on this site and I’m not the one making the decisions of what gets featured when, so I can’t really give you much feedback on that.

I will say that I’m going to be focusing mainly on the more established franchises first. I think an all-time Rockies team or an all-time D’Backs team could potentially find itself looking very dated in five to ten years. I don’t see nearly the potential for as much change with teams like the Reds and the Tigers.

Erik Bedard and Jeremy Guthrie over Mike Cuellar? That is going to require some explaining.

The issue with looking at the Orioles pitching with the early late 60’s 70’s is how much of their success can be attributed to pitching and how much can be attributed to defense. When you have Brooks Robinson, Paul Blair, Mark Belanger and Bobby Grich all playing behind you, you can’t tell me that doesn’t help out the ERA some.

The catch 22 with it is guys Culler is that they pitched a way that worked and I mention several times in the first article that this is a difference between value and talent and I think this is one of the ways it gets illustrated. Talent is inherent, value is intrinsic and can be changed by factors that have nothing to do with a player’s overall ability. A groundball pitcher in the early 70’s would have much more success with Baltimore than anywhere else in baseball.

How good of a pitcher would Mike Cuellar have been without the same caliber defense behind him? We don’t know and this is aiming to figure how these players would fair in modern day vacuum which is something that can’t be tested, which brings in an element of uncertainty that can’t be eliminated.

Why Guthire and Bedard over Cuellar gets into how I factored in proportionality. The best season I have from Cuellar is ’69 when he wins the Cy Young in a year where I had evaluated 360 pitchers total. Jeremy Guthrie’s best season comes in 2010 when I had evaluated 633 pitchers in total. I can say the best pitcher from ’69 is better than the best pitcher from ’10 and even the second best pitcher from ’69 is better than the second best in ’10 but if you keep doing that at some point you have to conclude that pitchers from 1969 are just inherently better than pitchers from 2010, which also means either the hitters from 2010 are better than 1969, or that the caliber of talent in ’69 is just better than what we saw in 2010, which is era bias.

Because there’s more pitchers in 2010 than there were in 1969 I can’t put Cullar’s ’69 season (where he was 10th in WAR) over Guthrie’s 2010 season (where he was 8th in WAR) without also saying ’69 just inherently had better pitching.

I can be consistent with how I treat players, but I don’t think there’s any way I or anybody can actually be fair. There’s just too many built in factors to eliminate.

First off, let me say that you have made quite an achievement here with 2 years of work. Guys like Jennings are definitely under the radar picks.

However, I’m concerned about methodology. There is no link between the Baltimore Orioles of the 1800s and today.

On top of that, you say that you are factoring in FIP here, but then ignore that McNally had a career FIP of 3.49, and Cuellar’s was a career 3.29. Boddicker had a 3.80 career FIP, Flanagan’s was at 3.84, and McGregor’s was 4.06 (clearly a low number), but you are ignoring the fact that Guthrie’s low FIP over his only 5 years in Baltimore was 4.44. Tillman has played as long with the O’s as Guthrie did and has a career 4.43 (lower than Guthrie’s lowest season on the team).

On top of that, you justify through WAR but mis-state the reality. Guthrie was 58th in WAR in 2010 at 2.5 and Cuellar was 8th at 6.6. I’m not sure what you are reading from, but Guthrie whether through pitching WAR or through FIP has no business being anywhere near this list. He’s never been in top 10 for any team in WAR. In all Cuellar was top 10 in MLB WAR 3 times!!! McNally wasn’t, but he had finishes of 11th and 13th, and his overall tally was over 33 WAR, whereas Guthrie’s career WAR number is 11.7.

…source Fangraphs.

While there is commentary about how much team defense effected pitching stats, you don’t mention how team defense and weaker hitting affected how coaches coached. The pre-steroid era was one where pitch-to-contact was preached by managers and coaches, especially for those pitchers who weren’t blessed with Doc Gooden dominant stuff. Guys like Frank Tanana extended their careers significantly by changing philosophy. Listen to Palmer talk about pitching philosophy and you will see the realities of paradigm.

Imo, this group isn’t really representative of the real all-time team, and you often take liberties with some players, such as Boog Powell, that you didn’t take with other players, and included players that really shouldn’t be included at all.

I concur, the “reasoning” used in this piece is highly inconsistent and occasionally downright ridiculous. Choosing Hughie Jennings over Brooks Robinson is an outrageous and indefensible move that screams “Look at me! I’m different and obscure!” It’s absurd. If you have a player who was one of the greatest shortstops of all-time, you don’t move them to third base until they can’t play shortstop anymore. For an all-time team, you would never do it at all. Clearly that was only done here to shoehorn Hughie Jennings into the conversation when there was no legitimate reason to do so. The only thing for which Jennings is historically notable was his ability to get hit by pitches.

That’s reasonable. I just figured that Cuellar’s prolonged run of success would outweigh the short bursts of success from Guthrie and Bedard. Whatever weight you give to the defense behind him, Cuellar was very good for the Orioles for seven years.

Oh no doubt. Cuellar won a Cy Young and was multiple time all-star with the Birds in their heyday. Its a valid question with no real answer, just opinions with varying degrees of how well they are thought out.

To kind of flip the Cuellar question a little, how do you have Scotty Erickson on the roster when he essentially had one really good season and was nothing more than a stat filler innings eater with (seemingly) gaudy win totals and little else. Isn’t this essentially your argument against Cuellar (besides your point about better defense in 60’s/70’s O’s) and Cuellar was clearly the better pitcher of the two. In Erickson’s best season as an Oriole, 1997, he was arguably only the 3rd best starter ON HIS OWN TEAM. And even if you want to downgrade Cuellar’s Cy Young, that’s one more than Erickson won. So I’m sorry, but this isn’t really a “no real answer” issue.

That being said, I really like your first team list and look forward to the rest (and poking holes in all your choices – because after all, it is much easier to criticize someone else’s work – right?)

Well the two guys in front of Erickson on that ’97 team are Jimmy Key and Mike Mussina two dominant pitchers in their own right and that’s also a team that won 98 games and finished second in the AL in ERA, so to that’s more a testament to how dominating that team was than it is a knock on Erickson.

You are right in that I’m putting Erickson on the team for the same reason I’m keeping Cuellar off, but another factor is keeping the era’s proportionally represented and that’s where Erickson makes his gains on Cuellar.

On the master list I had Erickson with the Orioles was ranked at 1480, while Cuellar was 1621, which is a lot closer than it sounds. It’s equivalent of comparing Ron Darling with the Mets against Bob Knepper of the Astros and there is where it really gets hard because there is no clear cut choice.

With either Cuellar or Erickson I’m probably getting an innings eater and not much else, which isn’t a true representation of how good either was, but this is also a league where great is average and good is not good enough.

I’d put Cal Sr. on the coaching staff somewhere, if only for his ability to teach so many the “Oriole Way”.

I’d have no problem with amending it to have Cal Ripken Sr. as the third base coach over Al Bumbry.

The coaching choices were more for fun than anything and I wouldn’t take any of the choices that seriously. But I will admit that I glossed over the tenure that Ripken Sr. had as the third base coach with the O’s and even with my “choices” I did try to keep some elements of realism involved. Smoky Burgess is not going to be any team’s first base coach for instance.

If I had to go back and do it again, Ripken Sr. would be the third base coach.

On the subject of fun coaching staff choices, your mention of Dirty Jack Doyle, “one of the game’s most colorful players in one of its most colorful eras” (L.Spatz, SABR’s Bio Project), is my favorite decision in this article.

Interesting exercise. All of the ground rules make this approach more challenging than it might appear at first, and there’s plenty of room for “Player X > Player Y” cases, but that’s part of the idea. Looking forward to how you handle some of the other franchises. Thanks.

Thanks for the positive feedback.

The coaches were definitely one of the more fun parts for me to do and it’s because you can find ways of throwing in guys like Jack Doyle who wouldn’t otherwise make it.

It’s also a similar reason why I did the one name only rule which becomes very tricky to implement once you realize how intertwined these teams are. Bobby Grich is arguably the greatest second baseman in Angels history. They lose out on him.

Frank Robinson is a tough pill to swallow, but it won’t be the toughest. There’s players who have won Cy Young’s and MVP’s with multiple franchises.

But overall yeah that rule makes this project a lot more difficult than it would have been otherwise.

you cant leave players of mire than one team and you cant splitt teams of two or more cities other wise interesting

How in the world do you have HOFer Wee Willy Keeler essentially “in the minors” when he is a left-handed and a good OF (#1 in the NL in fielding % in 1901 and ’02) which you state as two of the weaknesses of the team. I mean how much better is he than the Ken Singleton/Brady Anderson platoon? Is there even a comparison?

It’s possible I missed the intent of the “expanded roster” section in your long criteria at the top, but he isn’t a starter or platoon on this team and since he’s on this list I assume he isn’t on the NY (AL) team – right?

First Keeler only has five years with the Orioles which is the fewest of any outfielder on the 40 man roster. That’s one thing that hurts him. Throw in his Brooklyn years and its a different story, but five years is all I’m basing him on and a main reason why I have Brady Anderson who effectively spent his entire career with the Orioles ahead of him even though all-time between the two Keeler easily wins out.

He’s also behind Singleton, Powell and Kelley in terms of OPS+ and as mentioned before all three played longer with the Orioles than Keeler.

As for his fielding, with any outfielder from the 1890’s-1900’s its a question mark in terms of their ability. So much more of the game is played on the ground back than as opposed to now it would lead me to believe that if a player had any kind of defensive ability they would be on the infield.

There is no 1890’s version of Paul Blair to be found as far as a great outfielder who derives most of their value from defense. The way the game is played just doesn’t allow for that type of player to develop.

That’s my biggest issue with the list as well. It looks like Keeler played more seasons for the Highlanders than Orioles (7 and 5), but he was a much better player for the Orioles, totaling 27.9 WAR versus 10.3 for the Highlanders.

Neat article and I can honestly say I learned a bit as I never really knew much at all about Hughie Jennings before. I really like the detailed explanations of why certain players were shifted position-wise in the interests of making a stronger team, or why players from various eras were considered more or less strongly than others in context. It’s a take on the “all-time teams” lists I don’t recall ever really seeing before and is clearly a labor of love to some extent.

I’m curious where Machado would fit in on the overall rankings at 3B. Obviously he’s not surpassing Brooks or Ripken yet (though if he has a 20+ year career with the O’s at this pace then it’s a conversation), but I thought he’d be on the 40-man roster in Tejada’s spot, especially after the intro talked about how it could be a place to stash some current players that just need a few more years under their belt. I guess he’s just under the margin of games played at SS to be considered for both positions so Tejada is a more useful option there.

Regardless, great read and I look forward to seeing more.

Thanks for the positive feedback.

Manny is definitely moving up the all-time Oriole rankings, but as it is already no matter how you set up the left side of the Orioles defense your benching a no doubt Hall of Famer.

Machado himself could have a Hall of Fame career entirely with the Orioles and still not make the 25 man squad. That’s just how deep the Orioles are on the left side of the infield.

In terms of where Macahdo would rank on the depth chart at third, coming into the season I had him fourth after Ripken, Brooks, John McGraw and Miguel Tejada, but he may overtake Tejada at the end of the year and may even catch McGraw just with another year or two like the one he’s having this year.

As great of a start as he’s off to though its still a long way to go before he can even think about catching either Ripken or Brooks.

jennings didnt have long time in the league he wss good but not ad gooos as brookks on def and he played much longer so i would but brooks at third and ripken at ss with belanger backing on def

Somewhat surprised not to find even a mention of Dave McNally? I know you deduct some for the guys backed up by the great O’s defense of that era, but still……he was a damn good pitcher for a long time.

Grich at SS? No way. He didn’t play SS for the Orioles, he was strictly a 2B. If he played a few games at SS during his tenure with the Orioles, does that really make him eligible for that position? Mark Belanger was the starting SS when Grich became a regular at 2B after Davey Johnson was traded and he was still the starting SS when Grich departed for California as a free agent after the 1976 season. Take him off the list and you can squeeze Bordick in.

Cuellar did pitch in a different era, with a better defense and in a pitcher-friendly park. But using your reasoning (that we have to imagine how they would fare in the modern game) certainly Cuellar’s K rate would’ve been higher than it was. Cuellar had a fantastic screwball but he also pitched during a time when hitters were more contact oriented than they are today. Because the average hitter today sacrifices contact for power, K rates for pitchers who were not nearly as talented as Cuellar are inflated.

I just can’t see Guthrie over Cuellar if for no other reason than he didn’t have any one pitch with which he could dominate hitters. When Cuellar had that screwball going RH batters made very weak contact with it. Today it would’ve been weak contact and a plenty of punchouts.

Grich did start out his career with the Orioles at shortstop and does qualify for the position, but before you say Belanger is the better option at short than Grich, think about what the list is really saying. The same player is also the best option at second and he can only play one position at a time. If both Jennings and Ripken were to get hurt, BOTH Tejada and Belanger would be called up. Belanger if nothing else would be used as a late game defensive replacement. Defensively he’s good enough to be argued as the best defensive shortstop in AL history. The problem is his OPS+ is 68. In a league where almost every pitcher was an All-Star at some point in their career, let’s just say he’s not batting lead off.

Jeremy Guthrie over Dave McNally and Mike Flanagan? Please explain?

Number of top 10’s in WAR amongst Orioles starters:

Sadie McMahon 4

Scott McGregor 2

Erik Bedard 1

Mike Cuellar 1

Scott Erickson 1

Jeremy Guthrie 1

Dave McNally 1

Mike Flanagan doesn’t have any.

This is how I’m looking at it. The best pitcher of the bunch can almost depend on what day of the week it is.

It’s not the idea that Cuellar could be a better option than Guthrie that I don’t buy into. It’s that he’s that much better of a replacement.

It’s not like I had much positive to say about Jeremy Guthrie. What I will say is that each era in MLB history is fairly proportionately represented, think about what that might really look like. If people are constantly bringing up me leaving out pitchers from the late 60’s-early 70’s or undervaluing them, it tells me people really don’t agree with that philosophy.

I see what my problem is. It is that I am being subjective, whereas your model excludes subjectivity. As a lifelong Oriole fan, steeped in the stories and memories of that franchise, Guthrie means little to me; whereas McNally, Cuellar and Flanagan — even Steve Stone (with his one great season) — are important. Those four were part of great eras in franchise history.

It is your model, you get to do what you like, but you’re probably in for some similar questions as you move forward.

I really appreciate all the work you must have done on this project. I can’t wait to read the rest of the series. I have no argument with your team except for Guthrie. I really can’t see putting him ahead of any of the other pitchers mentioned. You seem to base much of it on his slightly higher peak but even though bbref WAR has him 8th in the league in 2010 I see he is only 29th by fWAR and only 16th by their version of RA9 WAR. Even at his best, I just can’t see how he was any better than the other guys.

And I see that in Cuellar’s big 1969 season bbref has him tenth in the league with 4.5 WAR, while fangraphs credits him with 7.8 RA9 WAR and 2nd place. That seems like a pretty big difference.

It is a big difference. One system has him as one of if not the best #2 starters in the league, the other has him as a true #1. Had I had that season rated that good instead of what Baseball-Reference had him at, Cuellar would have made the 40 man squad at the very least.

Its not something that should be disregard either. Anyone that would do something like that and look at their picks as be all end all’s doesn’t know what they are talking about, because the more time you spend doing something like this, the more you realize how much uncertainty really lies in these rankings.

When is the next installment of the series?

Sorry for being late to the party. This is really cool. I think there are some legitimate gripes made here, particularly with Jennings as that’s a different franchise. That said the most glaring omission isn’t mentioned. The O’s bullpen coach absolutely without question is Elrod Hendricks. Grant Jackson? WTF?