Card Corner Plus: Five Who Have Left Us

It was Marty Appel, longtime Yankees public relations director and prolific author, who once said, “When a ballplayer dies, we tend to remember him by how he looked on his baseball cards.”

Exactly. That is what comes to my mind when I hear that a ballplayer from my youth—and I’m generally talking about a player from the 1970s or ’80s here—has passed away. I immediately recall the baseball card images of that player, often starting with my favorite card, and descending from that point.

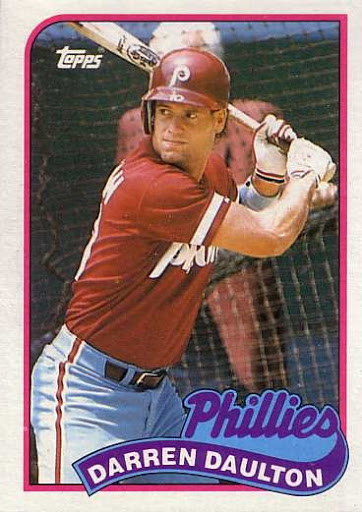

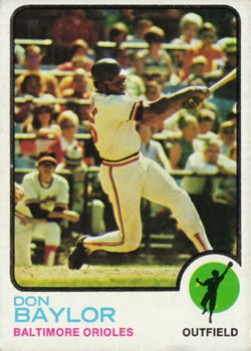

Unfortunately, I have had too many instances of such baseball card recollection in recent weeks. It started with the passing of Lee May, who died on the Sunday of Hall of Fame Weekend. It continued with the somewhat expected news that Darren Daulton died after a long battle with brain cancer. And seemingly within moments of his death, we heard that Don Baylor had succumbed to multiple myeloma, a disease that had plagued him for more than 10 years.

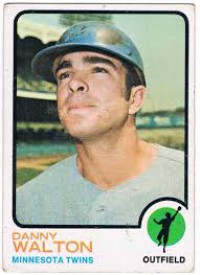

The bad news continued a few days later, with the announcement that Paul Casanova, an excellent defensive catcher in his prime, had died, only a few weeks after his appearance at the All-Star Game Fanfest celebration. To make matters worse, we also heard about the death of Danny Walton in early August. Walton was a onetime minor league phenom who was expected to become a power-hitting star, but instead had a journeyman’s career, albeit a fascinating one filled with its shares of downs and ups.

Perhaps it is a sign of advancing age on my part, but I remember all of these ballplayers, and not just by their names. I watched all of them play, and I have more than one baseball card for each of them. For me, and for many other fans of my generation, they are not just names or statistics, but players who bring to mind specific visual images. Although I never had the pleasure of meeting any of these players, I still feel like I knew them. I guess that’s one of the benefits of investing time as a fan. When I’ve seen a player on TV or at the ballpark, and when I have a baseball card of him, I feel I’ve achieved a level of familiarity.

Lee May’s death generated a few headlines and some national coverage, mostly because of his association with the early editions of Cincinnati’s “Big Red Machine.” (He hit 34 home runs for the 1970 Reds, the first team to be referred to as The Machine.) But for me, May was much more than a burly slugger for the Reds. When I thought of May right after hearing about his death, I immediately recalled his 1972 Topps card, which actually designates him as a member of the Houston Astros.

Lee May’s death generated a few headlines and some national coverage, mostly because of his association with the early editions of Cincinnati’s “Big Red Machine.” (He hit 34 home runs for the 1970 Reds, the first team to be referred to as The Machine.) But for me, May was much more than a burly slugger for the Reds. When I thought of May right after hearing about his death, I immediately recalled his 1972 Topps card, which actually designates him as a member of the Houston Astros.

This was the first card that Topps produced of May after the historic trade that sent him to Houston as part of the package for Joe Morgan. Actually, May is wearing a Reds uniform and cap in the original photograph, but the Reds logo on his helmet has been replaced by the airbrushed logo of the Astros. Since the Astros uniform featured a reddish-colored scheme, Topps left that part of the picture untouched.

Beyond the airbrushing, which was a fairly standard Topps practice for the day, the card stands out in my memory because of the visible way that May is sweating in the photograph. The heavy perspiration on his face is quite clear, as if the Topps photographer had just pulled him aside after a spring training workout and asked him to pose quickly for a shot, without even giving him a chance to towel off.

Come to think of it, it’s not the only card that shows May sweating. Look at his 1976 Topps card with the Baltimore Orioles. His skin is glistening slightly, showing some moisture from a day’s workout, or merely some pregame batting practice. Now maybe May was simply a guy who perspired a lot by nature, but it also indicates to me that he was a player who worked hard at his craft.

Come to think of it, it’s not the only card that shows May sweating. Look at his 1976 Topps card with the Baltimore Orioles. His skin is glistening slightly, showing some moisture from a day’s workout, or merely some pregame batting practice. Now maybe May was simply a guy who perspired a lot by nature, but it also indicates to me that he was a player who worked hard at his craft.

May was known as a leader, too. With the Reds, he served as one of Sparky Anderson’s lieutenants. If a problem began to brew in the clubhouse, perhaps some tension between two teammates, May could defuse the situation, bringing it to a resolution before it even made its way to Anderson’s desk. It probably also helped that May’s frame registered 6-foot-3 and 200 pounds. When Lee May spoke, when he tried to bring some reason and logic to the clubhouse, other players tended to listen.

Darren Daulton’s cards are not as memorable to me as those of some of the other players who have passed away in recent weeks, but his 1989 card stands out. I like the 1989 set to begin with; the design features both simplicity and artistry, while also conveying a three-dimensional look, especially the way the team name in bold script jumps off the surface of the card. In this case, I like the shot of Daulton during batting practice. His facial expression, with his lips pursed together tightly, conveys intensity, which he regularly carried over to the actual games. The card also shows off his classically athletic build and his handsome face; if you looked for a catcher out of central casting, the chiseled Daulton would have been an ideal choice.

Looks aside, Daulton may have been the best catcher in Phillies history. (In 1993, he walked 117 times, which seems almost impossible for a catcher, given the limits they face in terms of games played and at-bats.)

Looks aside, Daulton may have been the best catcher in Phillies history. (In 1993, he walked 117 times, which seems almost impossible for a catcher, given the limits they face in terms of games played and at-bats.)

Daulton, with a more outgoing personality than May, also provided leadership to his teams, particularly that group of 1993 Philadelphia Phillies. He had a wild streak to his personality, but compared to many of his fellow Phillies from the early 1990s, he played a role as a voice of reason. On a team with extreme, difficult-to-manage personalities, including Lenny Dykstra, Curt Schilling,and Mitch Williams, Daulton served as a kind of policeman, restoring some sense of order when it seemed like the clubhouse might fracture into two.

He also knew how to approach a player on an individual basis. He did exactly that with a young Dave Hollins, who was pouting after a poor game early in 1993 even though the Phillies had just swept a three-game series. Daulton noticed Hollins’ behavior and began “staring him down,” as Hollins described it. Even without words, Daulton’s message got through: don’t brood over individual failure, especially when the team is winning. Thanks in large part to Daulton, the Phillies did plenty of winning in 1993, advancing all the way to the World Series.

Much like Daulton and Lee May, Don Baylor carried a huge and respected presence in the clubhouse. Like a lot of fans, I tend to remember Baylor from his older years, when he added about 20 pounds to his frame, most of it sheer muscle. His 1985 Topps card has always been a favorite; even in the on-deck circle, with his huge arms and massive torso, Baylor could intimidate opposing pitchers. In this photo, he looks like he’s ready to eat the cameraman if he steps much closer.

Much like Daulton and Lee May, Don Baylor carried a huge and respected presence in the clubhouse. Like a lot of fans, I tend to remember Baylor from his older years, when he added about 20 pounds to his frame, most of it sheer muscle. His 1985 Topps card has always been a favorite; even in the on-deck circle, with his huge arms and massive torso, Baylor could intimidate opposing pitchers. In this photo, he looks like he’s ready to eat the cameraman if he steps much closer.

In reality, Baylor was a gentleman, one who tended to speak softly, in contrast to one of his Yankee managers, Billy Martin. Not surprisingly, the two did not get along. Baylor simply had no use for Martin, whom he considered unfair in his dealings with him. When Martin became aware that Baylor had taken on an adversarial role in the clubhouse, he decided to appoint the first “tranquility coach” in the history of the game: Willie Horton. Martin hired Horton, an impressive physical specimen of his own, to carry out his words in the clubhouse, and also to send a message to Baylor that he, as manager, was in charge.

The 1985 season would turn out to be the swansong for both Baylor and Martin in pinstripes (though Martin would return later). After the season, George Steinbrenner fired Martin, replacing him with Lou Piniella. The following spring, the Yankees traded Baylor to the Boston Red Sox for Mike Easler. Baylor, with his right-handed power and immense leadership skills, helped the Sox win the American League pennant.

By this stage of his career, Baylor had become a relatively one-dimensional slugger. It’s easy to forget the kind of all-around talent he brought to the table during his early days with the Orioles. Baylor’s diverse game brings to mind his 1973 Topps card, a beautiful action shot that shows Baylor near the completion of his swing, his bat pointed majestically and dramatically toward the outfield. (The Orioles’ batboy, seen in the background at Memorial Stadium, is certainly paying attention.) In this early career photograph, Baylor still looks muscular, but he is far leaner than he would become in his Yankees and California Angels days.

By this stage of his career, Baylor had become a relatively one-dimensional slugger. It’s easy to forget the kind of all-around talent he brought to the table during his early days with the Orioles. Baylor’s diverse game brings to mind his 1973 Topps card, a beautiful action shot that shows Baylor near the completion of his swing, his bat pointed majestically and dramatically toward the outfield. (The Orioles’ batboy, seen in the background at Memorial Stadium, is certainly paying attention.) In this early career photograph, Baylor still looks muscular, but he is far leaner than he would become in his Yankees and California Angels days.

Not only could this version of Baylor hit, but he could steal bases, too. From 1972 to 1979, he stole at least 22 each year, topped by the 52 that he swiped for the Oakland A’s in 1976, as part of Chuck Tanner’s run-and-stun offense. The younger Baylor was a four-tool talent, a player who could hit for average and power, steal bases, and play a decent left field. All he lacked was a strong throwing arm, the result of a serious shoulder injury that he suffered playing high school football.

If there’s one regret among the Baylor card collection, it’s that none of his cards show him running the bases. Baylor was one of the game’s smartest and most ferocious baserunners. Along with Hal McRae, he slid harder into second base than any player I’ve ever seen, making middle infielders shudder, or at least think twice about planting themselves on the double play pivot. Baylor’s takeout ability would be lost in today’s game, given the rule changes regarding what runners can do, but in his day, Baylor made the double play takeout an art form.

Baylor’s 1973 Topps card is one of my favorites; so is another card from that year, the one that showcases Paul Casanova. It’s one of the best from 1973 Topps, a beautifully photographed shot of Casanova rounding third base and heading home. The Topps photographer has captured Casanova at just the right moment, as he is cutting the bag and making a dash toward home plate. The color is also brilliant here, the blue of Casanova’s jersey contrasting nicely with the bright green of the artificial turn and the left-field wall.

As we can see on this action shot, Casanova did not have the stereotypical fireplug build of a big league catcher. No, he was long and lean, making him appear at first glance to be a shortstop or a center fielder. His running style was also impressive. His fists clenched, his arms extended, Casanova shows an understanding of the fundamentals of the game, as evidenced by the proper way that he makes the turn by stepping toward the inside part of the third base bag. This is how to run the bases, folks.

As we can see on this action shot, Casanova did not have the stereotypical fireplug build of a big league catcher. No, he was long and lean, making him appear at first glance to be a shortstop or a center fielder. His running style was also impressive. His fists clenched, his arms extended, Casanova shows an understanding of the fundamentals of the game, as evidenced by the proper way that he makes the turn by stepping toward the inside part of the third base bag. This is how to run the bases, folks.

Just like his Topps card, Casanova’s career has long fascinated me. A native of Cuba, he actually started his professional career in the Negro Leagues, playing for the old Indianapolis Clowns. From there, he bounced around several minor league teams, drawing a couple of releases, mostly because of his lack of power. Others would have given up the dream, but Casanova didn’t, eventually finding work in the Washington Senators’ farm system and later making his debut in the American League, where he showed off one of the greatest throwing arms of the era. One year, Casanova threw out 51 per cent of base stealers. Another year, he threw out 49 per cent. In terms of throwing, he was the Latino version of Johnny Bench—before Johnny Bench actually existed in the major leagues.

Casanova played the game with flair, enthusiasm and constant hustle. He once caught all 22 innings of a marathon game, then told reporters that he wasn’t tired and could have gone another 10 innings. His personality made him an extremely popular teammate, especially in Atlanta, where he became friends with star players like Hank Aaron, Dusty Baker and Ralph Garr. Everyone liked Casanova.

After his playing days, Casanova became something of an unofficial ambassador of the game. Settling into his home in Miami, he opened a baseball academy, where he taught hundreds of kids how to play the game with proper fundamentals. The academy became known as “Paul’s Backyard,” a place where kids felt safe to go and receive a baseball education.

At one time, Danny Walton was a heralded minor league prospect, a young right-handed slugger whom some scouts and fans likened to Mickey Mantle. In fact, at one point his teammates called him “Mickey.” That comparison, always an unfair one, likely placed a heavy burden on Walton, who posted an OPS of .790 for the Brewers in 1970 (and made the cover of The Sporting News that season), but otherwise struggled to gain traction in the major leagues.

Like Casanova, Walton was featured as part of the 1973 Topps set, and it was this card that immediately came to mind when I heard of his passing. Even though the card designates him as a member of the Minnesota Twins, he’s actually wearing the road colors of the Brewers, his former team. Rather than airbrushing, Topps simply obliterated the Brewers’ logo from his helmet. Notice how dirty that helmet is, which I suppose is appropriate given the lack of cleanliness and order to Walton’s fragmented career.

Like Casanova, Walton was featured as part of the 1973 Topps set, and it was this card that immediately came to mind when I heard of his passing. Even though the card designates him as a member of the Minnesota Twins, he’s actually wearing the road colors of the Brewers, his former team. Rather than airbrushing, Topps simply obliterated the Brewers’ logo from his helmet. Notice how dirty that helmet is, which I suppose is appropriate given the lack of cleanliness and order to Walton’s fragmented career.

After making the rounds on 1973 Topps, Walton did not appear on a baseball card in 1974, ’75, ’76 or ’77. That’s because he spent much of that time in the minor leagues or on the Twins’ bench. After the 1975 season, the Twins traded him to the Los Angeles Dodgers for second baseman Bobby Randall. Walton appeared in a few games for the Dodgers, but never made it to a Topps card wearing Dodger Blue. During those in-between years, Walton became a prodigious Triple-A slugger, adding to an eventual total of 238 home runs in the minor leagues. After the 1977 season, the Dodgers traded him to the Houston Astros, setting him up for a return to a Topps card in 1978.

The contrast between Walton’s 1973 and 1978 cards has always struck me. The dark, bushy eyebrows are common to both photographs, but his hair is much longer by 1978, and he appears to have put on a significant amount of weight. Even though only five years had passed, Danny Walton looks like a completely different man on his 1978 card. It would be his last card; Walton slid into retirement and became known for his love of riding motorcycles.

The contrast between Walton’s 1973 and 1978 cards has always struck me. The dark, bushy eyebrows are common to both photographs, but his hair is much longer by 1978, and he appears to have put on a significant amount of weight. Even though only five years had passed, Danny Walton looks like a completely different man on his 1978 card. It would be his last card; Walton slid into retirement and became known for his love of riding motorcycles.

All ballplayers age, often in undesired ways, sometimes adding unwanted extra pounds. Sadly, these ballplayers continue to age in retirement, just like everyone else. And then we lose them, just as we have lost Walton, Casanova, Daulton, Baylor and May in recent weeks. For a fan who saw them all, and remembered them all, it hasn’t been an easy time.

But then I take another look at them on their baseball cards, when they were still young, still in their prime, and still worthy of another visit from the Topps photographer. These cards bring back good feelings. I guess this is how we prefer to remember them, but what we should really be doing is thanking them. These ballplayers were good enough at their jobs to make us care, to want to have their cards in the first place. For that, we should be grateful. With a friendly reminder available to us through these cards, we won’t be forgetting them.

Excellent article. I recall an earlier version of Casanova’s card (1967?) when he was kneeling and his catcher’s mitt was taking up what seemed like 95% of the picture. Just raw memory. Lee May had another distinction: he played for both Earl Weaver and Billy Martin. He had a namesake (Lee Maye) who also did a stint with the Astros. Marty Appel is dead on but hedged his bets with the word “tend.” I would add two other memory joggers to the list: Strat-O-Matic baseball cards and front covers of The Sporting News. The former for stats and the latter for images. You nail it for Walton. I remember that he started out very well in 1969 or 1970 and was on the front cover of TSN in the first part of the year. I just checked old covers of TSN. This is surreal. I cannot believe it!!!! On the cover, there is an image of Walton swinging his bat. And guess who the catcher is! Yup. Paul Casanova!!!

Great article. I will share with my OBC friends.

Nice remembrance of these five men, Bruce.

Lee May never played for Billy Martin. But he did play for three Hall of Fame managers (Sparky Anderson in Cincinnati, Leo Durocher in Houston and Earl Weaver in Baltimore). It was Rudy May who played for Martin and Weaver.

Had the Houston Astros fired manager Harry Walker at the end of the 1971 season, like they almost did (and perhaps even more likely had the Cubs similarly fired Leo Durocher, making him available earlier), instead of mid-way into the 1972 season, the blockbuster Cincinnati-Houston trade probably never happens. This could also mean the Astros are the big surprise of 1972. If Houston wins the division (or pennant or the Series) under Durocher, he’s almost certainly inducted into the Hall of Fame while still living.

Had the Dodgers not traded for Danny Walton and instead hung on to Bob Randall (who the Twins wanted so they could move Rod Carew to first base), the Dodgers (providing Randall was not out of options) would likely have brought him up to L.A. to start the 1976 season at second until Davey Lopes’ spring training injury healed. That would have meant the Dodgers not trading right fielder Willie Crawford to St. Louis for second baseman Ted Sizemore and probably not later trading catcher Joe Ferguson to acquire Reggie Smith (to fill the hole in RF created in the Crawford for Sizemore trade).

Many people remember Don Henderson as the hero of Boston’s dramatic comeback in game 5 of the 1986 ALCS over the California Angels with the Red Sox down to their last strike. Boston would win that game in extra innings on another RBI by Henderson and then go back to Fenway to take two more and win the American League pennant. But often forgotten is that without a two-run home run two batters earlier in that same top of the 9th by Don Baylor with one out, the Angels would have gone to the World Series before Henderson even would have got a chance to bat.

As you mentioned, Bruce, Darren Daulton’s 1993 stellar season featured him being walked 117 times. Johnny Bench never topped 100 and Mike Piazza’s high was 81. I believe Daulton’s total rank 4th on the single-season list for most walks by a catcher. It’s one of those weird anomalies, given that he hit .257 with 24 homers and also struck out 111 times. (He was passed intentionally 12 times). Daulton usually batted 5th, with Pete Incaviglia or Jim Eisenreich most often on deck when he was hitting.

Paul Casanova credited playing winter ball in Venezuela for improving his game. “I owe it to Venezuela that I made it to the major leagues,” he said. When he retired from the majors he opened a restaurant in La Guaira, a port city in Venezuela. In that 22-inning marathon game in June 1967, Casanova went 1 for 9. His only hit? A game-winning walk-off single at 2:24am. Senators Manager Gil Hodges gave Casanova the rest of the day off (there was a night game the same day the extra-inning game ended). But the following day, Casanova started and completed both games of a double-header against the Yankees. Later in his career Casanova caught Phil Niekro’s only no-hitter.

To Phillip: Dave Henderson (not Don). And thanks for the tidbit on Daulton’s walks. I never realized that.

I was born in 1970, and first began buying baseball cards late in the 1978 season. As a result, I had relatively few cards that pre-dated that year, especially the further back before 1978 you went. Somewhere along the line, however, I acquired Paul Casanova’s 1973 card. It may have been the first 1973 card I ever owned, and for a long time it was certainly one of, at best, only a few that I had from that year.

As I grew older, I began to buy some older cards at card shops and the like, but I mostly stuck to 1975 and later cards, or cards of certain players I liked, and I never really had a lot of ’73s.

Today, anytime I see the phrases “Paul Casanova” or “1973 Topps”, my mind immediately pictures Casanova’s ’73 Topps card.

Dennis, I may have misquoted Marty Appel slightly. I’m not sure that he actually included “tend” in his statement. I was going by memory. But he was right on, whatever the case.

Re Martin & Horton:

Mr. Hostility hires Mr. Tranquility…

Has an interesting ring to it.

Another wonderful article Bruce. I immediately thought of Baylor’s 1979 Topps card, which showed this huge broad chested powerful man (leading the AL in RBIs when I was collecting it) smiling at the camera.

For a great picture of Baylor taking a player out at second, check out the 1973 Frank Duffy card.

Also, check out the 1973 and 1983 Topps cards of Baylor, which upon first glance I considered the 1983 card a reprint of the 1973 card. Even the batboy in the same place. Obviously someone at Topps liked the 1973 card and