Learning the Language of the Clubhouse

Not everyone that loves baseball speaks the same language (via Keith Allison).

“NEERRRRRRRRRRD”

Darwin Barney was yelling at me. All eyes in the clubhouse were now fixed on me, wondering who let the nerd in. Just a few weeks before, I’d been in a similar situation and had felt terrible and small. This time, though, I was prepared.

“Hey man, I was just telling you you had trade value,” I said back to him with an exaggerated shrug, loud enough so he could hear. He was laughing. This was fine.

Minutes earlier, I had been waiting for Anthony Rizzo to talk. With veteran players, the fact that nobody recognized me was sometimes a bonus. A.J. Burnett gave me a great interview last year, supposedly because he thought I was a national guy, said one of the regular Pirates beat writers. But Anthony Rizzo didn’t recognize me and I’d bothered him before I saw his earphones in. Whoops. He wasn’t going to take them off for me, so there I was thumbing through FanGraphs.com on my phone, looking for someone interesting, someone with an interesting stat under the name, at least until Jeff Samardzija was ready to talk again.

Darwin Barney was bouncing around the clubhouse in front of me, but I wasn’t sure I had an angle. It was close to the trade deadline, and like many other Cubs, he was speculating on possible trades. Involving himself. But he couldn’t see any trade value in his skill set.

“Hey,” I offered, “by some defensive metrics you’re the best defensive second baseman in the league.” Barney smiled at me, maybe incredulously. The Cubs beat writer next to me was sharp: “Best in ‘the league’ the league or in the National League?,” he asked. I had to admit Dustin Pedroia had a better UZR. I tried not to say the word UZR, because I’d learned, the hard way. After a quick conversation about which contending teams might want a defensive second baseman (“Marco Scutaro is a very fine player,” Barney said with a glint in his eye), Barney was bounding across the room to his locker and my fate was sealed.

The episode was light-hearted, and the result was a few laughs and maybe a confused stare or two. Hopefully that was because I’d learned some important truths about language in the clubhouse over the preceding months.

Last year I was accepted as a member of the Baseball Writers Association of America (BBWAA). Though I’d been in the clubhouse for a couple of interviews with R.A. Dickey and on the field for blogger media days in New York, it was the first time I spent regular time in a professional locker room. Things that you “know” in your head just have to be learned with on-the-job training. Things like: when to go into the clubhouse, when you can be on the field, when to bother a player, which players you can talk to, and when you can take a picture.

Most of those things can be chalked up to just learning how the clubhouse works, just some on-the job training comparable to learning the ropes of any new position. But for me, in particular — wanting to ask players questions about stats and the available sabermetric research — learning the language of baseball was the most important part of the process.

I knew it wasn’t going to be easy from the start. At my first BBWAA event, upon my introduction, a question shot out of the lunch crowd — “FanGraphs, aren’t you the guys that ranked the Giants last the year they won the World Series?” That was Hank Schulman’s welcome call. He followed it up by coming over to tell me later that he was engaged in a “war on stats.”

But my relationship with Schulman itself provided me a road map to the year that was to come. Instead of shaking my head and wishing him good luck on his crusade, I pried. Nothing is that simple. And after a great conversation completed mostly using the simple language of baseball as it is played on the field and executed in the dugout and the clubhouse, we even came to some agreement: Statistics might be a better tool for the front offices. On-field management might sometimes be better served looking at things other than the numbers when making decisions. I now count him as one of my friends in the media room, and he was the first person I turned to when I wanted to learn more about being a beat writer.

All it took was a little calm conversation, minus the words “rate,” “ratio” and “correlation.” But I didn’t learn the lesson completely there.

Early in the season, there were a few fits and starts. One of my earliest interviews was with Ryan Vogelsong at Giants media day. I wanted to ask him about his FIP, and, well, I thought I should try explain to him what FIP was:

“Given your strikeouts, walks, and ground balls, your FIP, which is usually more steady than ERA, has been higher than your ERA — you’ve been sort of over-performing these stats that people have come up with. I think this is really interesting because given your history, and given all that you’ve had to overcome, you’ve been under-rated in the past, too. Is there anything you can say about the way you pitch that might look like more than the sum of the parts? Is there something you play ‘up?’ How would you define yourself as a pitcher?”

Good lord. I’m lucky he let me get all that out. He might not have in the clubhouse. But media day is a little different — the players are stationed and ready to talk — and I was lucky enough to have Vogelsong alone. The fact that his eyes were glazing over flew over my head, really. Since he gave me a good answer (he bears down with runners on base and prefers a walk to a home run in those situations), I felt vindicated. When I talked to George Kontos next about platoon splits on sliders, I thought the job might even be easy.

Slowly, I started accumulating interviews that didn’t make it into an article, though. Sean Marshall didn’t have much to say about first-pitch strike rates, and Todd Frazier didn’t know how he’d struck out less often than his swinging strike rate predicted. Jedd Gyorko didn’t have anything particular to say about park effects and home runs per fly ball. Some of this was about the personalities of each player, but some of this was also about the questions I was asking.

All of this is prelude to the time I really stepped in it.

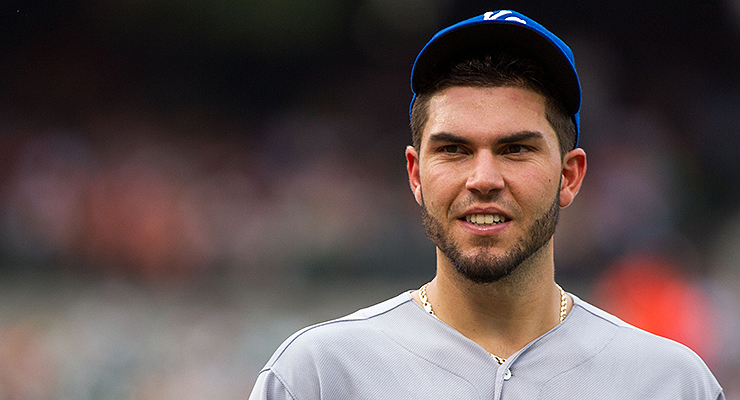

And, despite all that has come before… it started because I was poorly prepared. Standing in the Royals’ clubhouse, I realized I wasn’t sure I knew what Eric Hosmer looked like. Whether it was because he was normally wearing headgear or that I hadn’t seen the Royals live yet that year, I was unsure. I turned to Google image search, my trusty sidekick in moments like these. What followed immediately must be user error, however.

I walked up to Eric Hosmer on the bike and said “You know, I’m Greek too! My father’s side.”

Woof. Hosmer didn’t get it at first, but when he did, whoo boy. He laughed, so I laughed, but then he brought in Jeff Francoeur to join in the laughing, but, hell, I’ve laughed at myself most of my life, so I continued smiling even as more people joined in with the laughing at me, and the pointing and the barbs. He doesn’t really look like Mike Moustakas! It was kind of funny! Sort of.

Really, I had some experience with this sort of muck-up. I’d walked up to Cory Luebke’s locker early in the season, failing to notice Dale Thayer’s beard on the man I approached with questions about Tommy John rehab. I’d asked Yuniesky Betancourt if he was Alfredo Figaro. In both previous cases, I’d powered through and at least managed a conversation with the player, just in case something turned up. (It didn’t.)

So in this case, I took the same tack. I apologized and asked the first baseman if he had some time to answer questions anyway. Maybe I shouldn’t have bothered. It was clear I was getting shove-off answers. I had wanted to talk about his ground-ball rate but “you just want to go up there and play the situation.” Does he think about changing his swing to get more loft? “Everyone has gotten to this level” using their natural swing. Speed? “You just want to go out and play the game.” It would take some digging to salvage something from this one, I realized. I thanked him for his time.

I hadn’t prepared for Billy Butler, but he was available-looking. So I called up his FanGraphs page and looked for some nuggets. I noticed that his walk rate was higher than his strikeout rate for the first time in his career. And I knew that he’d always been a ground-ball guy. I headed over.

As the first words came out of my mouth, I realized the error of my ways. This man was nicknamed Country Breakfast. I had just asked him if he’d noticed that this year he’d been showing “his best walk rate.” He looked at me incredulously. “Is that a question?” I noticed a cavalcade of laughs joining in behind me as I laughed. Uh-oh. “Have I noticed that I’ve walked a lot?” he was almost yelling. “Yes,” he answered with an eye roll. More laughs. The recorder has me there, distinctly, at the moment of discovery that I had an audience: “Oh man.”

I tried to bring it back to baseball language. “Was it a point of emphasis in the spring, you’ve always walked a lot, but a career high seems notable.” Butler was settling in for a regular interview at this point, still with a bit of smile on his face as he put his shoes on: “I don’t think anyone goes up there thinking they’re going to walk,” he said. Informed that this might be the first year he would walk more than he struck out, he said, almost with air quotes in the air… “cool.” More laughs, and I realized it was Eric Hosmer with… oh yup, Mike Moustakas.

What I’d been looking for was some insight into the ideal ground-ball rate for a hitter. The Royals were hitting the most ground balls in the league, and I thought it might be affecting their power. Since I knew Eric Hosmer was the one behind me laughing at me, I thought I’d be the adult. I asked Butler about ground balls, but I motioned at Hosmer (I see you there): “I was asking Eric about this, but are ground balls and fly balls something you think about when you get up to the plate?”

“I think about putting the barrel on the ball.”

The peanut gallery exploded. “He gets paid to put the barrel on the ball, you guys get paid to think about fly balls and ground balls,” offers Hosmer clearly on the tape. Which wouldn’t be so bad, he’s right. But as I finished up the interview — Butler was great, he admitted that he looked for the low ball, since the pitcher was trying to throw it there anyway, something I found very interesting in terms of game theory — there was a hum behind me that threatened to take away my concentration.

I didn’t know who exactly was talking, but the tone of the stream and the intent was clear: “we get paid to put barrels on balls man, what the f— is this guy talking about, walk rates, ground-ball rates, barrels dude, barrels, what’s up with this hair, must be because he’s Greek, yeah or blind, these are some stupid questions, man, I’ve never heard anything like this, dude needs to shut up, bothering us about ground-ball rates man, barrels, dude, barrels, nut sacks more like.” The interview with Butler had been getting better, but there was one last emphatic statement from the trio behind me before they exited: “This guy’s the f—ing worst.”

There’s a pause on the tape, where Butler stops talking and there’s no follow-up from me. It’s painful to listen to, now, even 10 months after it happened. Butler noticed, and to his credit, asked: “You all right?”

I rallied. I tried to indicate that it wasn’t all him with some looks at the guys walking out. I finished up with some good material for a piece on ground balls. I thanked Butler for his time, and we ended on good terms. I got some great stuff from Alex Gordon minutes after.

But there was that moment, when three baseball players announced that I was the worst at my job they’d ever seen, and walked out of the clubhouse shaking their heads in tandem in agreement at how terrible I was, there was that moment burned into my memory. In that moment I relived all the moments in which I had felt small and unwelcome, all rolled into a ball and highly concentrated. It might be a credit to my parents that all I did was blink a couple times and stammer to Billy Butler that I was “just a little rattled.”

What was to blame for that moment? Maybe bad preparation. Maybe a bad Google image search. Maybe my haircut. Maybe the strange setup of clubhouse interviews that sometimes requires opening lines that sound like they belong on the singles scene. Maybe two young players encountering their first bit of trouble in the major leagues.

On some level, though, it was my choice of words that day. Since that day, I don’t think the word “rate” or “ratio” has come out of my mouth in the clubhouse. Why use them, when you’ve got words like “swing plane” or “loft?” Words that their hitting and pitching coaches have used, words they’re used to.

My very first interview happened to be with an elite player who was happy to talk about his batting average on balls in play, but that didn’t mean everyone else was comfortable talking about those sorts of things. And really, being able to put complex topics into easily understandable language is important — think for Joey Votto, express yourself for Eric Hosmer, maybe.

Or: learn the language. It’s the same as learning the rules, really.

Nice story.

Has your interaction with players changed how you talk to media personnel or typical fans? Do you write articles differently now?

I just know the terms I want to use now. Seriously should have spent more time talking to hitting and pitching coaches before I went in, because those guys are stat to game translators.

What was to blame for that moment? Maybe Eric Hosmer is a giant asshole?

There’s a very good chance Hosmer is an asshole, but it’s pretty weak to go into the clubhouse to interview players and not know who they are. Not sure it’s “the worst” but certainly a bad way to start a relationship.

I’m a Royals fan, and this article kind of makes my skin crawl. I’m disappointed those guys were such dicks. Man up, gentlemen – you still have a LOT to prove.

Sounds like the year in high school where I brought up sabermetrics at the lunch table. I was ridiculed and laughed at as well. Almost made me quit loving baseball. But it’s over now and I’m better off now. Nerd power.

Nice article. Enjoyed it.

Hoo, boy, you take me back. It’s not quite a “learning the language” thing, but it was my low point as a beat writer for a year covering the Pirates 30 years ago.

Chuck Tanner was the manager. He had Rich Hebner on the team at the time this happened. I was in the clubhouse before the game and saw Hebner there, but for some reason it didn’t register with me that he was in street clothes instead of in uniform.

Comes a situation in the ninth with the Pirates behind where Tanner needed a LH pinch hitter and instead sent up a RH who made an out and the game was lost.

So when I got a chance in the manager’s office after the game to do so, I said, “Chuck, was something wrong with Hebner?”

He was smiling but his eyes narrowed. “Why do you wanna know?”

“Because if he was available in the ninth, you’d have used him to pinch hit.”

“Yeah,” he said, “I was gonna pinch hit him. I was gonna get him out of a f***in’ sick bed.”

“So he was sick, I didn’t know that.”

“Then,” Tanner said, “you must not be doing your f***in’ job.”

So now the rest of the media contingent is dead silent, until someone quietly asks another question, and I want to slink off somewhere.

There’s a punch line, however. Charlie Feeney, who wrote for one of the Pittsburgh papers at the time and was source-wired like nobody else, knew everything and everybody that was happening, and now is in the writer’s wing of the Hall IIRC, wasn’t in the room at the time. He shambled in a minute or two later, stood off to the side until he got a chance, and said:

“Chuck, was something wrong with Hebner?”

There was a tense moment until Tanner said, “Yeah, Charlie, he said he was sick so I gave him the day off.”

Now some people are laughing. I sputtered out, “You yelled at ME when I asked that!” But I was laughing along with everyone else.

My favorite story from my beat year, with the possible exception of Dave Parker asking me, “How come I never see you out chasin’ no pussy?”

RIP Charley Feeney:

http://www.post-gazette.com/sports/pirates/2014/03/17/Longtime-Pirates-beat-writer-for-PG-dies-in-New-York/stories/201403170161

Heisenberg is refusing to let you muck up the game by letting you inform player about the game they’re playing in blessed Newtonian ignorance.

Nice write, I like the concept of having to dumb yourself down and creating a new language.

The “clubhouse” sounds a lot like H.S.,

I hate baseball a little more now….

I loved playing baseball in HS, but frankly the players were mostly a bunch of stupid assholes. Stupid as in complete morons with 100 IQs. Anything that stretches them intellectually will be ridiculed, because it’s just too far over their head. That’s why you got that kind of response from the players. In thinking about it, unlike other sports, baseball players have too much time just standing around. That’s in practice and games. So, riding each other and players on other teams becomes an art form. So, you have to learn to roll with the punches…. or seriously kick somebody’s ass. Otherwise, it just continues forever.

Excellent read, it’s always interesting to hear about the inner workings of the clubhouse. Thanks for sharing your experiences.

I will (probably unfairly) dislike Eric Hosmer going forward.

Great story, bud. I’m not sure when the Royals interviews were, but if it was last Spring, you should have asked Butler about his incredibly high FB/HR “tendencies” the year before and informed him he was likely to see a substantial dip in his home run total (from 29 to 15)… that woulda caught his attention I bet 🙂

Tough to calculate that in a split second in the clubhouse though 😉

Great story, Eno. Reminds me of the fine line (that I often cross to the wrong side of), of telling an embarrassing story about yourself, intending to make a point and/or be funny, that could easily end up as just uncomfortable for all listeners if handled wrong. You nailed it. Well done.

That said, I think there’s a good lesson in here for anyone who cares about baseball analytics. There’s no use communicating– written, spoken or otherwise– in a way that can only be understood by people who have already taken the time to learn a certain amount of the content, or who already agree with a certain way of seeing things.

Said another way, it isn’t about dumbing anything down for players, or a clubhouse. It’s about talking about things the way people talk about things. Constantly trying to understand more and more about baseball and the way it’s played is a worthwhile endeavor. UZR and all the ratios and correlations that Eno got himself to stop saying have all helped the process. But if you need to know what UZR is to understand a story written about how good someone is on defense than the writer has failed in writing the story, just like Eno learned to get more out of players when he started using terms the players themselves used.

That’s not a lesson particular to advanced statistics writing either. Writers of all types could do a better job stripping their work of jargon. Baseball is only unique in that many of the principles involved in the field themselves are unfamiliar with the jargon used to describe what they do.

You could have just told Moustakas that he was the worst at his job that you’ve ever seen unless his job is pop out with RISP.

I’m pretty sure most of us would not want to talk/hang out with 99% of MLB players.

Eh, it’s probably like most walks of life. Some nice people, some not-so-nice. Some bright people, some not-so-bright. I definitely think it makes certain sense to talk about baseball more on the conceptual level than using technical terms when talking to non-SABR types. Often, the understanding is still there, just not in numbers form. And if there’s not understanding, well… they probably don’t have much interesting to say any way and move on to someone better.

Haha, well, any time you can sit there and gain wisdom from two guys who can’t combine their numbers to equal Kevin Mass, you gotta view it as a learning opportunity. Though from what you wrote, it sounds like they both believe your on-base percentage ticks upwards if you’re on defense standing near first and third.

That said, if you do happen to piss them off at some point this season, at least you don’t have to worry about Hosmer or Moustakas grabbing a bat and hitting you with it.

Imagine if the guys in the Royals clubhouse actually knew all the things FG had written about the organization!

Really entertaining piece. The Greek comment was great; too bad they acted juvenile.

I remember as a kid giving the wrong baseball card to a player after a Cubs game at Wrigley. I will never forget Mike Harkey(or his mustache).

Two things:

1) Bad on you for not knowing what arguably the two best players on the team look like. I mean, come on, not knowing a simple fact about your subject is a pretty terrible thing.

2) Now that I’m done giving you a hard time, I’d like to offer a simple theory: Guys playing baseball, generally, are stupid. Most are not educated past high school, and many with the talent for the big leagues probably stopped caring about learning around age 15 when they realized they were going pro. Every now and then a ballplayer went to college, think Will Venable or Trevor Bauer, and everyone wants to rave about how they’re geniuses (Princeton! Engineering!), simply because they obtained a college education. That should lend some insight into the pathetic cognitive state of most ballplayers. The fact of the matter is that baseball players are not academics, and (with some exceptions) they don’t understand even the basic aspects of statistics, rates, regression, etc…so we should not expect them to. For the most part they are “see the ball, hit the ball.” I’m not sure why we’re expecting guys who have been nothing but successful at what they do through every level to deviate from what they do based on mathematics they aren’t even capable of comprehending. For the most part we’re talking about unsophisticated, stupid people who happen to be extremely physically gifted.

Under-rated and possibly #firstworldproblem is this: it’s hard enough knowing all the stats for all the players, which I do, but adding picture research (which I will do more of) for entire teams is another wrinkle that I had hoped to avoid by using the names on their lockers. It’s worked for the most part.

I prepare for about eight players a day, it’s all I have time for given my other commitments at this site. I hope I get those eight players. When I don’t, I have to work on the fly. I’ve gotten great interviews I didn’t plan for, and then this happened too.

I wouldn’t recognize Eric Hosmer if he had a Royals uniform on. Yeah, I know the name, and yeah I know he supposed to be a good player eventually. But let’s face it, he’s nowhere near a national stage playing for the Royals and being a marginally good player. I’ve never seen him play once.

No reason to try to humiliate someone for not recognizing you. Talk about hubris. Yes, you should have been better prepared but their responses were immature, shallow and show they truly have low self esteem despite their macho head games. People mess up my name or think I’m someone else all the time but who cares? It only matters what you feel about yourself.

I really enjoyed that article, Eno! It was a nice respite for me, as I constantly scour the internet and read analytical pieces. I enjoyed bucdaddy’s story too.

If you guys want to see what it is really like for someone to act like a dick when another person is trying to do their job, watch some of the video from Justin Bieber’s deposition.

You guys are crazy. Those two wouldn’t be the franchise players on the Storm Chasers. I guess they got angry and bailed because Eno was throwing softball questions with his left hand.

In five years this is going to come off like Ben Grieve pulling a dont-you-know-who-I-am act.

Eno,

Great article! I grew up in the baseball world and know the jock attitude that goes on among players. I could literally visualize the situation. You are correct there is a learning curve. Just like in life there are the really nice considerate guys and there are the ones who enjoy messing with you.

Eno, congratulations on gaining this access. I think you can be a pioneer of sorts. Even if you had some rude comments, look at the way you were able to turn Butler’s attitude around after he initially kind of rebuffed you. You change minds one at a time.

I didn’t see the situation you described take place and there’s no doubt Hosmer and his pals have some growing up to do. As far as Hosmer taking things as far as he did, I would imagine a lot of his tone was probably as a result of his pals ribbing him about the misidentification and getting him fired up over it. 24 year olds are still pretty susceptible to being goaded into doing stupid things. This is not to excuse his behavior as much as to understand why it happened. I’m fairly certain it wasn’t because he really thought you were the worst at anything. I’m sure Hosmer heard his share of inane questions during his terribly grim sophomore slump. If I were you, I would look him square in the eye and try to interview him the next time you meet. Maybe he’ll surprise you, or maybe he’ll just confirm that he’s not worth your time. Either way, the attitude will evolve over time and you will be a big part of that. It happened with the old school reporters and front office types (to a large degree) and it will happen with larger numbers of players, too.

“No, I didn’t mistake you. You aren’t Greek? I thought the “s” was silent!”

But seriously, anyone who has played sports at a somewhat high level knows there is a difference between busting balls in the clubhouse (which, to be fair, is the player’s domain) and being a dick. The former is a healthy part of sports, this was the latter. There is a reason Butler was embarrassed.

Eno, I just want to congratulate you on how far along you have come as a writer and on your continued success. I remember when we used to write together at Baseball Guys back in the day. I stopped writing when Fanball folded and just enjoy playing fantasy sports now and enjoy the game, but I know how difficult this job must be for the full-time writer. I found it a little too tough to tackle a writing gig to go with a full-time teaching position. Whenever I come across those that are critical of writers, I try to explain how tough a task it truly is. I bet this was a tough piece to write. I hope it goes better in the future when you go into the clubhouse. Anyway, I’ve truly enjoyed reading your pieces over the years and I wish you all the best at this job.

-Larry Yocum

“Last year I was accepted as a member of the Baseball Writers Association of America (BBWAA).”

Eno,

On a tangent, I’m curious if you’re a member just as yourself or as a representative of THT, or how that works now that the BBWAA allows bloggers in. How are you credentialed?

Cut to the chase: I have a long history here and elsewhere of railing about working journalists in the BBWAA compromising (IMO) their integrity by voting for MLB’s major awards and the HoF. This has generally been directed at members of the old-school print establishment and the publications they represent. I don’t think working journalists have any business conferring sometimes lucrative honors on the people they cover, aka sources. I can be pretty dogmatic about it. So can, for instance, the New York Times and the Washington Post, whose codes of ethics forbid their employees from voting for such awards (the Heisman and the like included).

But I’m wondering if I should regard the blog community differently somehow. No doubt, many writers such as yourself consider yourselves to be “working journalists.” I’m certainly on board with that, if you cover and write about baseball as a full-time job. I give you that respect. So I’m leaning toward thinking you should be held to a similarly high standard. But if there are any blog codes of ethics (as there are in the newspaper world), I’m unaware of them. Are there? Or is it more of a “let your conscience be your guide” kind of thing? How does the blog community police itself? How does a site like THT set its standards of professional conduct, if it does?

I’m aware that if you make a mistake in a story, your readers will call you out, so it’s sort of self-policing in that way. I’m asking more about stuff no reader would ever see or know, the ethics of trust and integrity. Who or what keeps you in line?

There’s a guy at the Arizona Republic who wrote about his dilemma with the MVP vote for last season. He was caught between Andrew McCutchen and Paul Goldschmidt, and he wrote that if he voted for Goldschmidt, he risked looking like a homer, but if he voted for McCutchen, he risked pissing off a source.

McCutchen, by the way, has a clause in his contract that pays him $125,000 for winning the MVP vote.

Why, as a working journalist, would you ever willingly put yourself in that position? When all you really have to sell are access and credibility (and to bring this back to this post, you compromised your own credibility among the ballplayers by not knowing who you were talking to; it makes a funny story but it’s a serious thing).

I wrote to ask him if he considered he had a third option: He could choose not to vote at all, and simply explain that he felt it compromised his ethics.

Never heard back from him.

Anyway, the problem is, no reader can ever know what motivations a writer has for voting for the player, whether there were any promises exchanged (“I’ll vote for you if you give me an exclusive sit-down if you win”) or other shenanigans, but doubts can be at least assuaged somewhat by the knowledge that the organization the writer represents polices its employees on issues like these.

Do you have any thoughts or responses to any of this?

Thanks. I’m enjoying the discussion here.

I think the way that a site like ours can avoid any problems like the ones you are describing is by continuing to be married to the analytical, numbers-based approach. We aren’t too interested with sources and breaking news at FanGraphs, at least not right now. So currying favor isn’t something I’ve thought about much, actually.

Eno,

I admire your openness and honesty. Great story.

Dan

Great piece. It’s never easy being the “new guy” in the clubhouse, especially when the beat writers are around asking their usual questions. I think the important thing you point out is that once you get past the awkward stage and get comfortable knowing the clubhouse routine, it’s easier to find the guys who will give you a good interview.

Last thing: Don’t EVER delete those awkward interviews. You are going to want to go back and laugh at them years down the road. (Kinda like you did here.) I saved my early interviews I thought were great and quickly erased the embarrassing ones. Should have done the opposite.

This reminds me of the first time I was ever in a Major League clubhouse. It was 2006, and I was a graduate student doing some freelance writing for Indians.com. I didn’t know about the postgame routine – first stop is the manager’s office – so when I rolled into the Tribe clubhouse it was just me and the players. Ol “Intentional Balk” Bob Wickman had closed the game in a 1-2-3 9th. Wickman, of course, was known for his very sloppy appearances, so I went into the clubhouse thinking we could joke around about what a breeze tonight’s appearance was. And I mean, Wickman was (I assume still is) a roly poly guy. I’d always assumed he was genial. Also, this was maybe 9 minutes after the game ended, and Wickman was already draining the last of a Busch Light.

I went up to him and this is what happened:

“Was it too easy for you, Bob?”

“What?”

“Was it too easy tonight?”

“What the f%#^ is with you reporters?”

“Um?”

“It’s always the same s%^# with you guys.”

Now, the whole team is looking on, and I’m pretty sure Wickman is going to punch me. Seriously. Just a thick, furious closer from Green Bay looming over my so very frail frame.

“I don’t know what I’m doing,” I said. “I’m just a graduate student.”

He pauses, extends his hand.

“I’m Bob.”

“I’m Joe.”

And then Bob and I took a cross-country car trip. You wouldn’t believe the hijinks that ensued. (This part isn’t true. Also, I’m not totally sure the beer was a Busch Light. It may have been a Busch reg.)

My impression of Wickman’s time in Atlanta was that we was generally disliked by everyone, including Bobby Cox and the players. So, this doesn’t surprise me at all. Plus the guy was a world class sweater. Atlanta really didn’t work well for him. He probably needed to change uniforms after every batter.

Great piece and glad you survived.

New writers usually get harassed, just part of the initiation, and even when you’re dealing with an old guy like Billy he’s still a kid who has done one thing extremely well for his whole life. Hoz and Moose are even younger and the Handsome Frenchman was a seriously bad influence on them. They’ll mature one day, but will still be overgrown and wealthy kids who instinctively feel things that numbers may never quantify. For them it’s instinct, pounded in by the year-round honing of subtle motions, hundreds of swings a day. Yogi Berra once commented on trying to think and play baseball. Ted Williams once asked Mickey Mantle whether he was top or bottom hand dominant. Mantle went into a slump for two weeks trying to figure it out.

For stats, talk to the coaches. You’ll find some have data that will surprise you, since they have house Nerds to generate the stuff from the various F/x’s that aren’t available to the public. They combine that data with eyeballs and experience and make decisions, often instantaneously, such as whether to send a runner on a BIP and that based on vector, velocity, base runner speed, number of outs, hitter in the batter’s box, score, outs, outfielder’s arm and accuracy. They don’t have time for a spread sheet but they do do their homework and see the game in a similar manner to the nerds, but usually in a different language, since they talk to players instead of fans.

If you ever get to the K, introduce yourself to Lee Judge, Star columnist. He wrote a similar column a few years back. Good luck.

Fascinating article. I’m not sure you were necessarily treated any differently than ‘traditional’ journalists. What I take away from this piece is that players not only talk but also think about the game differently than we do. This is not surprising, since, unlike us, they can play it.

Okay… maybe it was just poor wording on your part, but it sounds like you’re saying because “unlike us, they can play [baseball],” they know better than us non-players? Their job is to play the game; not understand or analyze it. Just because they are ignorant of various baseball metrics doesn’t mean those metrics are of no value.

Baseball has been using metrics for a century, but the modern metrics movement is of more concern to the front office, agents, and fantasy players than it is to the guys who actually play the game.

I enjoy the metrics side, learned a lot, but one thing I’ve learned is that modern metrics is a microscopically fine slicing of box scores, an historical pursuit. Some people watch data, others watch the games. They have different cultures and different languages and don’t really have the game itself in common. That might make communication a little difficult.

Of course it doesn’t mean the metrics have no value. They’re our best chance as nonplayers to understand the game, since our experience on the sandlots, in Little League or in high school is so far removed from the reality of professional baseball as to be nearly worthless.

In other words, Steven, yes: when it comes to actually playing the game they know vastly more than we do. A very few of them are articulate enough to communicate that knowledge, but I find that I am nearly alone among sabermetrically-inclined fans in appreciating them, because I overlook their (not to put too fine a point on it) innumeracy. I’ll bet you know who I mean.

On that note I am looking forward to Fox’s experiment with putting Harold Reynolds and Tom Verducci in a booth together.

Pitchers tend to be more aware of their walk rate, homerun rate, groundball rate, etc. They have to know their strengths and the best way to attack hitters. Hitters are more concerned about whether they’re going to get a first pitch fastball or a 2 strike low and away slider than they are with their BABIP, FIP or things of that ilk. They just want to work to get a pitch they can handle and “put the barrel on it”. Some things aren’t that relevant if they are taking it one at bat at a time…. like they should.

Okay, there is some author ego here.

Good stories to tell, but Eno’s stat-minded disconnect from the actual game and its players…

To be around baseball players…

Great article. Funny thing is now, Mistakeus is one of the worst if not the worst hitters in baseball. Sorry they were such dicks to you.

It’s not you, Eno. I googled “Hosmer acts like a douchebag” after he hit the homerun in game 2 of ALDS. A Royals fan pretty much sums it up here: http://www.royaleswithcheese.com/2013/05/aloha-mr-hand.html